Hi! This is my first post here. I had been thinking about aesthetics for philosophical movements and ended up using Effective Altruism as a case study, so it felt appropriate to share the essay, first published here, on the EA forum. Note that it's not written primarily for an EA audience, and it is somewhat of an outsider's perspective. I've been familiar with EA for several years, but I probably got some things wrong anyway.

The most successful ideology of all time is arguably Christianity. It is two thousand years old, has about two and a half billion adherents, and has been the dominant religion of most of the most powerful countries. Few belief systems have come close, although the other big religions are in the same order of magnitude. If we ask the question of secular ideologies, then the strongest contender is probably liberalism, which has been at the core of the political and economic systems of the wealthiest states over the past few centuries.

Now let us perform a little exercise. After you have read this paragraph, close your eyes, and take a few moments to visualize Christianity. It won’t be obvious, since Christianity is an abstract idea, but you should be able to see something anyway. You can imagine the sounds, too. When you are done, do the same for liberalism.

What did you see and hear?

To my mind’s eye, Christianity immediately evokes magnificent cathedrals, spires rising into the sky, the play of light through stained glass, and elaborately ornamented architectural detail. I see Jesus on the cross, and indeed crosses everywhere: the cross is a simple symbol, easy to remix into countless variations. I hear organ music, and choirs singing, and bells ringing, and the hypnotic utterances of a priest during mass.

Liberalism is trickier to visualize, but some things come to mind too: the Statue of Liberty overlooking New York harbor. Lady Justice, blinded and watchful. Neoclassical buildings, serving as the houses of government or the law, with their white marble columns and stately appearance — a nod to the birthplace of democracy in ancient Athens. Sounds: the chatter of lively debate in a coffee house of the Enlightenment; the bustle of an industrious and ethnically diverse city; the scribbling a quill laying down the principles of political liberty.

These descriptions point to what we can call an aesthetic. An aesthetic is a coherent, recognizable style. It manifests in everything from architecture to music, clothing, poetry, storytelling, or website design. Aesthetics determine how beautiful a thing is, which is simply a specific way of saying how interesting it is.

Not all aesthetics are created equal. It seems clear to me, at least, that Christianity has a richer aesthetic tapestry than liberalism does. Yet liberalism still has an aesthetic. Other religions and philosophies have their own, with varying levels of definition: the relationship between an ideology and its art is not straightforward. The aesthetic of a movement can be intentional or incidental. It can derive from existing prestige and power, or it can be the cause of prestige and power (or a mix of both in a self-reinforcing feedback loop). It can obscure the goals of the movement through attractive propaganda, or make them legible by bringing to light a clear vision.

Whatever the situation, it should be obvious that aesthetics matter. They matter because they are unavoidable — if you don’t define them, they will be defined for you, probably in a haphazard way — and because they are often associated with success in some way. It would be a mistake to view them as a superficial part of your enterprise, a casual task that you can offload to some marketing department to deal with PR while you focus on “the important problems.” Companies, political parties and philosophical movements that ignore their aesthetics are poised to do less good for the world (at least according to them) than they could otherwise do. What could possibly matter more?

One such movement has been catching quite a bit of tailwind recently: Effective Altruism. Rooted in utilitarian ethics, Effective Altruism seeks to maximize the good that a person can do in their life by examining the impact of various choices, such as careers and giving to charity. With the recent launch of organizations such as the Future Fund, it has been able to mobilize large sums of money and is becoming an increasingly relevant part of the public discussion on global problems such as poverty and risk from artificial intelligence.

This is, overall, a good development. People making a serious effort at improving the world is great! But for reasons that I have had a hard time articulating, I have been unable to get enthusiastic about Effective Altruism, despite knowing about it for years and agreeing with most of the philosophy it rests upon. I have been led time and time again to the inescapable conclusion that Effective Altruism is the right approach, at least in theory — and yet I really balk at the idea of identifying as an effective altruist.

Why would that be? A possible answer is that I’m mistaken about my own beliefs. Perhaps, as a fallible human, I do not truly want to be ethical. Or perhaps utilitarianism is not the right framework for me. Yet neither of these things match my internal experience: I do think that people should try to do good, and my complex thoughts around utilitarianism lean towards it being at least as good as the alternatives.

A more likely hypothesis is that I dislike the current incarnation of Effective Altruism in the real world. That could be because of its social scene, for instance. But again that’s not quite it, since I interact with effective altruists often enough and enjoy doing so. Neither is it because I disagree with the priorities of the movement as I understand them.

Instead, the most interesting explanation I have at the moment is that Effective Altruism has an aesthetic problem. Its visual style is underdeveloped. Its ideas are expressed with dry and boring language. It inspires very little art. As a result, it has been difficult for me to get excited about contributing, or even to make sure that the values of the movement match mine. And I’m not the only one in this situation. The scientist Michael Nielsen recently said that a disregard of the arts by the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer may be a sign of something wrong in Effective Altruism’s very foundations. So we could reasonably conclude that Effective Altruism is made less effective and perhaps even less altruistic by the lack of intentionality around its aesthetics. If true, this poses a serious problem to the movement.

This is not primarily a post about Effective Altruism, nor is it a full-fledged critique. Rather, it is the perspective of an outside observer who wishes well on the movement, and who worries that a lack of aesthetic may be a larger obstacle than effective altruists may think. More importantly, it is a useful case study of a philosophy with minimal aesthetics, which we can use to examine three reasons why beauty matters to a movement: attracting people, making members feel good and remain involved, and solving the value alignment problem.

Most things that can be called a “movement” depend on recruiting members. This can be done in any number of ways, including rational persuasion, peer pressure, and outright coercion. But the best method is arguably seduction.

Religions understand this well — or at least, the ones that have survived to this day do. To thrive, a religion must gain new followers in either of two ways (or both): by encouraging its members to pass on the religious memes to their children, or by convincing non-followers to convert. In both cases, having a rich artistic and architectural tradition helps.

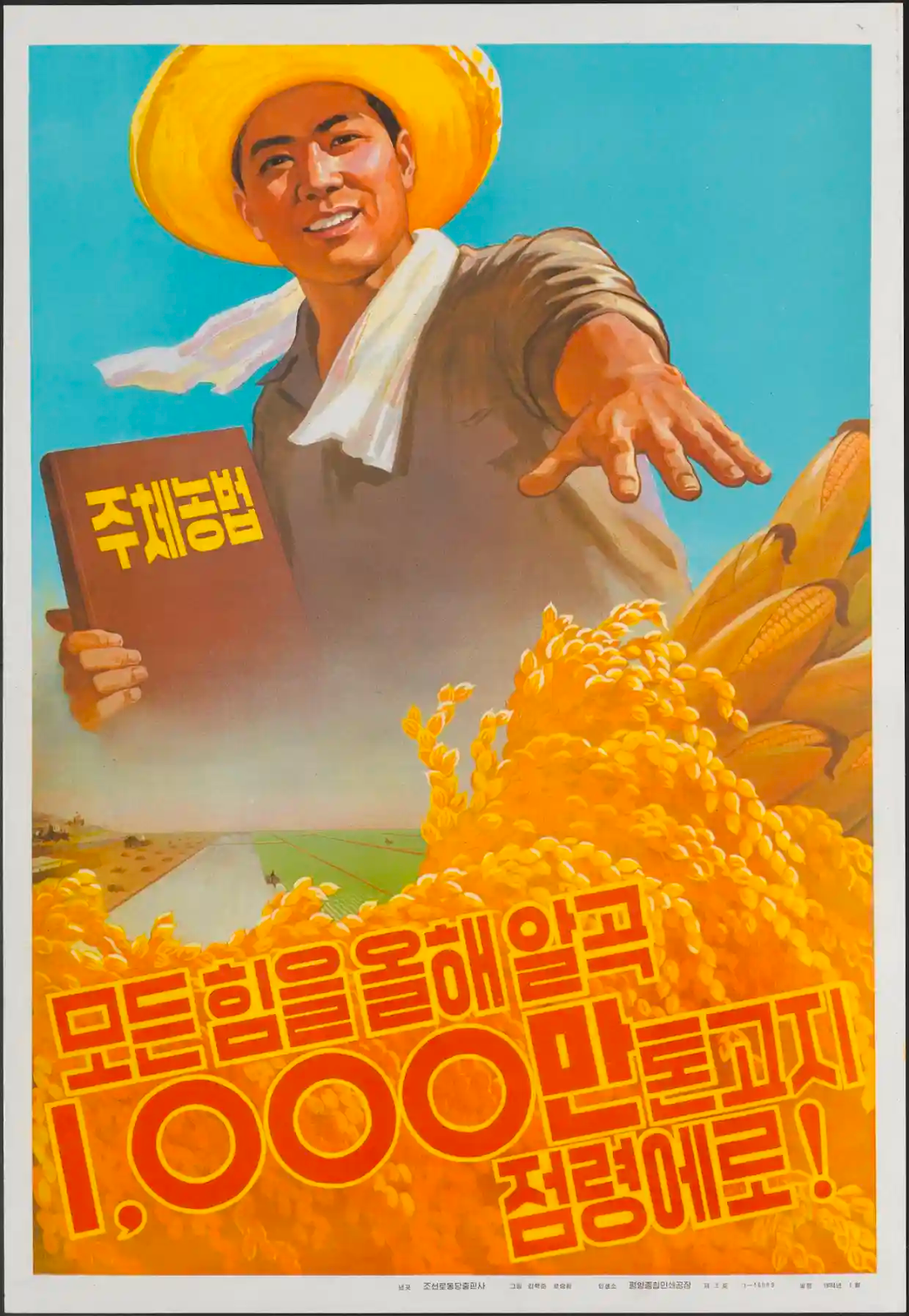

In politics, the art of gaining new converts is known as propaganda when it is done by someone in a position of power. Communist propaganda, with its clearly defined realist aesthetic, comes to mind. But aesthetics also matter for movements that are trying to gain power, notably in democracies in the form of political campaigning. Political parties engage in marketing, a term that also describes the act of seduction in the world of business.

The relationship between power and art is complex, and it seems common that aesthetics receive more attention not before, but after a seizure of power (which itself depends on the strength of ideas or of an army, or both). Once a new king has established a dynasty, he will commission monuments and lavish buildings to legitimize his rule. Once a revolutionary movement has taken hold of the capital, it will create art to show its moral superiority over the previous government. In this way, politics works differently than religion, whose focus on spirituality often means that the aesthetic experience is central from the beginning.

Therefore, I would hesitate to claim that a movement (or company) must invest in its aesthetics well before it has grown. At the start, resources are limited. There may be other priorities.

In the medium to long term, however, aesthetics matter. The reason is that they are what Scott Alexander has called a “symmetric weapon.” Once you are important enough to have competition (from other ideologies, parties, religions, companies, etc.), then ignoring your own appeal means that you will lose support to your competitors if they use their weapon. Unlike an asymmetric weapon — something like logic, which works well only for the people who side with truth — a symmetric weapon can be effective no matter who uses it. The Nazis can create inspiring art, and if you don’t counter with your own inspiring art, then you’re giving the Nazis a chance.

Some effective altruists are keenly aware of this. An essay from late 2021 argues that fun writing can save lives, since it allows important ideas to be read more widely and therefore improve their impact. (“Fun” isn’t quite the same thing as beauty, but can be considered part of aesthetics.) What’s quite fascinating is that the author spends more than half of the essay’s length anticipating objections such as “Won’t interesting writing lower the quality of the epistemics?” and “The highest impact people don’t care about it being interesting.” Her answers are on point, but clearly the issue is somewhat controversial among effective altruists. And all this preempting didn’t manage to catch everything: the discussion below the article brought up several other points of pushback.

Many of the comments were about a specific concern: the difference between mass-market and elite appeal. A piece of art or writing could be intended to reach as many people as possible, by using strategies such as clickbaity headlines or sexualized imagery. But you don’t always want to do this. In fact, sometimes you want the opposite: your aesthetics should seek to attract only a sliver of the population, to get only the best people and to avoid growing too fast. Arguably, Effective Altruism is one of these “elite-first” movements: the people who identify as effective altruists are expected to be highly-educated, sophisticated people who have given much thought to ethics and philosophy.

This concern is valid, and it adds useful nuance to my take. But it doesn’t contradict it. Even if your movement is supposed to be for the educated or the powerful, you still need to do the job of rallying those people. In fact, the small size of the elite, together with their generally higher means of achieving goals (due to wealth, intellect, and connections) means that competing for their attention is even more crucial to success. And whether they want to admit it or not, elite people are sensitive to aesthetics. A billionaire who agrees with Effective Altruism may pride themselves in thinking that they don’t care how “interesting” an essay is, as long as it’s correct and impactful, but they will be less likely to read a dry and boring essay anyway.

Put differently, the aesthetics you need depend on your target audience, and it’s very much worth worrying about that. But there does not exist a possible target audience for which aesthetics don’t matter.

Having attracted people to your movement, the obvious next step is to make sure that they stay involved. To make them stay, you need to provide them with something — such as joy, meaning, or interesting experiences. To achieve this, a sensible strategy is to surround them with beauty.

Think of two companies, both equally attractive on paper. One has dreary offices, dominated by the color gray, fluorescent lighting, cubicles, and practical desks and chairs. The other has established its workspace in an elegant old building, and filled the place with plants, sunlight, colorful furniture, and art. Which one is more likely to retain its employees?

There’s no need to belabor the idea that quality of life is important and that it depends in no small part on aesthetics. But it’s worth pointing out that while my previous answer — attracting strangers — framed aesthetics as a tool to be used, this answer is, in a sense, more fundamental. It shows that beauty is a basic need of believers that must be met. If it isn’t, then your believers will lose motivation and leave the movement or, worse, stay and slowly become depressed and suicidal.

This sounds dramatic, but it isn’t far-fetched. The most famous proponent of utilitarianism himself, John Stuart Mill, suffered from depression as a young man when he realized that accomplishing his goal of a just society wouldn’t make him happy. From his autobiography:

In this frame of mind it occurred to me to put the question directly to myself: "Suppose that all your objects in life were realized; that all the changes in institutions and opinions which you are looking forward to, could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?" And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered, "No!"

At this my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my life was constructed fell down. All my happiness was to have been found in the continual pursuit of this end. The end had ceased to charm, and how could there ever again be any interest in the means? I seemed to have nothing left to live for.

What saved Mill? You guessed it: poetry and the arts.

This state of my thoughts and feelings made the fact of my reading Wordsworth for the first time (in the autumn of 1828), an important event in my life. . . . [His] miscellaneous poems . . . proved to be the precise thing for my mental wants at that particular juncture.

Effective Altruism is based on the same philosophy, and as a result its adherents are at risk of falling in the same trap. As paraphrased from Twitter, there are many people who, in trying to “maximize utility,” just end up feeling “fucking miserable.”

This is not a trivial problem! It’s easy to say that an effective altruist should care about their own happiness and surround themselves with art, if that helps them maximize impact. But it’s tricky to do in practice, when you are used to calculating the impact of every dollar (or hour) that you spend. Sure, you could buy this nice painting for your living room, or spend some time learning to play music, but couldn’t you buy some malaria nets to save lives in Africa instead? Or work more at your high-paying job so that you can throw more money at the malaria nets?

At the core of Effective Altruism is the idea that we should “shut up and multiply,” which means ignoring our intuitions in favor of cold, dispassionate calculations of what is good. Since aesthetics are a key source of intuition on moral goodness, a utilitarian may be tempted to do away with them entirely — and thereby make themselves miserable.

To be fair, the tension between cold calculation and moral intuition has been central to Effective Altruism since its inception. The entire movement can be said to exist in reaction to most models of charity, which maximize the good feelings of philanthropists rather than their actual impact. It would be counterproductive to suggest that effective altruists give that up. But it seems plausible that their reaction has gone slightly too far.

Aesthetics provide an elegant solution to course-correct. They can add a layer of inspiration and emotional appeal to the sense of purpose that drives the movement, but which may not be sufficient on its own. And they don’t even require a huge investment of resources: commissioning some art would probably be just a rounding error in the big philanthropy budgets. So it may even be a good way to “maximize impact.”

More generally, this is a lesson that political parties should learn, too. With rare exceptions, political aesthetics are markedly poor, perhaps because parties try to appeal to everyone and end up with bland visual identities. As a result, there is very little joy that comes from being in them. I suspect that this is a major reason that people are dissatisfied with traditional political blocks.

Of course, it’s not easy to develop good and uncontroversial aesthetics, especially when you aim for broad appeal. But it’s something worth trying. Most religions show that it’s an achievable goal. (Incidentally, the lack of inspiring aesthetics may be why New Atheism has mostly failed as a movement, while religions are still doing just fine.)

The third and last reason that aesthetics are important for success is that they help determine what success even is.

A philosophical question: What is the point of art? Certainly a part of the answer is that art creates pictures, sounds, and stories that are pleasant to the senses. A more sophisticated thinker might add that art has a spiritual dimension: it is good for the soul as much as for the body. But even deeper than that, I think that art is a worthwhile endeavor because it forces us to pay attention to what is most important.

In other words, art is the main mechanism by which humans create visions of what they want. Our true desires are typically hidden by the fog of daily life and bodily needs, and we need to be challenged by a novel, a movie, or a painting in order to understand what these desires are. The process may be aspirational: a beautiful photograph of a landscape may make us realize that we have a yearning for nature. It may also be cautionary: dystopian fiction is about defining what kind of future we don’t want.

When a movement spends time and energy defining its aesthetics, it also, simultaneously, defines its values. It’s not the only way to define one’s values. But it often leads to different results than the other ways, like pure reason or religious revelation.

Consider the current state of Effective Altruism’s aesthetics, insofar as it has any. Its logo is a lightbulb with a heart in it. Its main website is clean, with teal as a dominant color, a graph as the first image, and not a whole lot of art. When I asked people online what they thought Effective Altruism’s aesthetics were, the answers revolved around spreadsheets, precision, math, and basic clothing.

To the extent that a vision of the future can be extrapolated from this, it seems to be a future of pure optimization, in which we do not waste our resources on flashy clothes or leisure time — or one in which we have replaced humans with robots who don’t suffer and are easy to make happy by incrementing a variable, thereby “maximizing utility.” I’m not claiming that these visions are what effective altruists actually want, but it’s hard to deny that they’re what their aesthetics suggest.

In fact, scratch that: if you haven’t put in any work to make sure that your aesthetics suggest the future you want, maybe you don’t truly want it. Maybe (some) effective altruists would actually be okay with a fully “optimized” world, in which all living beings are wireheaded to a system that feeds them a chemically-induced bliss.

Is that the world that effective altruists would like to see come true? Probably not, for most of them. But without art to show us otherwise, how can we be sure? If you’re an effective altruist who does not want this, how can you steer the movement away from what would otherwise appear to be its logical conclusion?

Success is not a good thing if you succeed at something that is morally abhorrent. So it is fortunate that aesthetics, in addition to helping movements succeed by attracting people and improving the lives of its followers, can also contribute to figuring out the right kind of success. In this way, it helps solve a problem analogous to the alignment problem in artificial intelligence: making sure that the values of a powerful non-human thing — a movement or an AI — are aligned with those of humanity.

Of course, aesthetics are not a guarantee of morality. The Nazis are a shining counterexample, with their elegant swastika symbol, their stylish uniforms, a taste for grandiose architecture, and ethics that were about as wrong as ethics can get. But then again, they liked to display skulls on their caps. Which led a fictional Nazi, in a classic British comedy skit, to wonder: are the Nazis the baddies?

So perhaps aesthetics are not a fully symmetric weapon after all. They can help reveal the moral worth of an ideology. They can show directly that a movement wants to bring goodness to the world, since art and beauty are good. Effective altruists and political campaigners may worry that aesthetics distract them from their goals, but that’s something only someone who’s afraid of firing the weapon would say — either because their goals are unclear, or because their goals are wrong.

Suppose you agree that aesthetics are important, and you want to provide your movement with some. What should you do? What kind of art should you aim for?

Any precise answer depends on the specifics, of course. For Effective Altruism, there are some interesting suggestions. Solarpunk is one. It is, with its focus on both nature and technology, one of the most common aspirational aesthetics, yet one that is, for some reason, almost never embodied by any real movement.

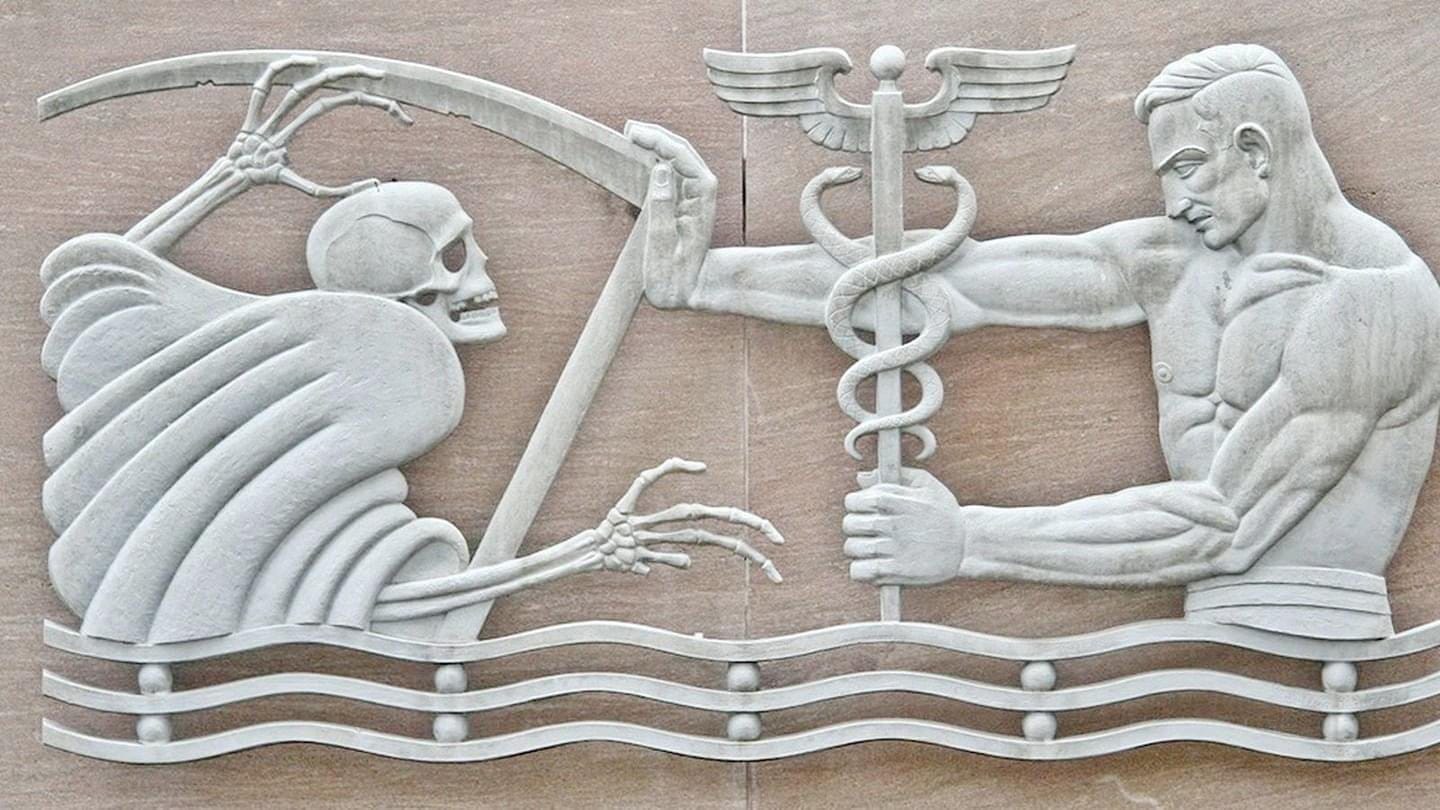

Another idea that I saw floating around an effective altruist discussion group is this modern sculpture from the Grady Hospital in Atlanta, to emphasize that death is bad and should be fought:

As a sign that Effective Altruism is not completely devoid of aesthetics, this poster for a recent event in Boston is also quite nice:

All of these are aspirational in very different ways. The solarpunk aesthetic in fact doesn’t please all effective altruists: some think that it carries with it the errors of environmentalism, which shuns industry even though industry has been the most efficient way we have found to increase welfare. Fair enough! Such debates are the whole process of trying to define your values through your aesthetics. As we saw, it’s not necessarily easy to reach consensus on these questions.

But let me conclude with a suggestion for an aesthetic that is, at the moment, underutilized. You see where I’m going with this: classicism.

Classical antiquity provides the foundation to Western culture — and, through Western influence, to the world’s. As such, it is an aesthetic choice that manages to be both fairly neutral and compelling, while also drawing from a rich artistic and architectural tradition. Yet for whatever reason, classicism is less in vogue now than it has been for most of Western history. So it doesn’t take a lot of effort to remix it into something original. Of course, classicism is more on the elite side of the aesthetic spectrum, since it assumes quite a bit of background knowledge on history and literature, but as we discussed, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

I shall make no comment as to whether Effective Altruism or any particular ideology should adopt the visual style of the Greco-Roman world. But I do predict that those who do are likely to find themselves more successful than others in the next few decades. Classical aesthetics have occupied the pinnacle of Western art many times in the past few millennia. They will again. And then the only question is: through which movement?

Further reading

- LARPing Up the Wrong Tree, my last essay for The Classical Futurist, can serve as a counterweight to this piece. It is about the dangers of making your movement solely about aesthetics.

- A call from 2019 on the EA forums to use art to convey Effective Altruism.

- Also from the EA forums, a very recent and widely read piece on current challenges in community building. Not directly related to aesthetics, but aesthetics could be a part of the answer.

- The results of a solarpunk art contest from last year.

- The effective altruist philosopher Peter Singer on the ethical cost of high-price art (2014).

I'll echo some of the other commenters: thanks for writing this, I appreciated the post! I don't entirely agree with everything you say, but I do really want to see more art and thought put into aesthetics. (On the other hand, I'm not sure how much of our resources we should put into this.)

You might be interested in:

Great links, thanks! I agree that how much resources is a core question. It seems plausible to me that there's currently a low-level baseline of caring about aesthetics, fiction, art etc. that has been sufficient so far, but EA will need a bit more intentionality as it grows.

Hey thanks for writing this. I didn't think I would enjoy this post but I did.

For me, the question is, how much resources should we spend on this? I like that EAG Boston had a visual identity but I'm unsure that every charity should be throwing money at Graphic designers.

So yeah, I'm not saying art doesnt have value but I guess that if people don't join the movement because the art isn't good enough then I'm okay with that. should I not be?

In particular, Instagram has many more women, Twitter has many more men. It's EAs bare aesthetic alienating groups who would join. I'd be interested in views there.

"How much resources aesthetics need" certainly is a central question. There's definitely a risk of spending too much. For an organization that is fairly successful, though, I don't think it needs to be a big portion of the total budget in order to get most of the positive effects.

I think it's fine to say that we shouldn't care about people joining EA because there's no art, which in essence means that my first argument about attracting people is irrelevant to EA (or relevant only in the narrower "elite" sense). I'm not sure it's truly the case, but EA has been successful enough so far so you could totally make that point. I do think that the other two arguments are more important to EA.

Lovely post, I really enjoyed reading it. I honestly never really cared for having an EA aesthetic because a) many EAs are minimalistic and as long as the logo on shirts etc. is nice, all is well and b) keep your identity small; as long as the arguments are correct and convince the relevant people, you shouldn't even need a name like EA stuck to it.

However, I also totally see the value of an aesthetic and things really are more fun when they look nice. I personally am full on board the solarpunk train (as long as it is only non-sentient plants amidst my industrial complexes)

But still, for now, I still feel like the EA identity should be kept as light as possible although I don't have any good answers for when aesthetics should start to increasingly matter.

That's a reasonable take. It depends ultimately on what EA tries to be. It could be, for example, a small node of "elite" people which coordinates other organizations that do care more about their aesthetics for their instrumental goals. In that case minimalist aesthetics serve the purpose well. If EA tries to become more mainstream — or even if it becomes mainstream due to some external factor, like the media starting to pay attention — then it's possible that it would need a more elaborate aesthetic to showcase its values.

I have a similar sense. Very interesting post and food for thought.

But how would better aesthetics lead to positive impact? The mechanism I'm seeing is essentially "compliance" with views commonly held within the effective altruism community, or some other form of persuasion that doesn't require understanding or agreement. There are exceptions where this would be helpful, but I expect this sort of persuasion to be net negative for effective altruism overall. (Low confidence.) As well as the post JasperGeh links to, here's a recent one making some relevant points: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/xomFCNXwNBeXtLq53/bad-omens-in-current-community-building

Additionally, when I tried the OP's exercise of closing my eyes and imagining aesthetics for liberalism, I couldn't think of any. I asked my friend (not involved in EA but very intelligent, well-read, politically involved) to do the same and they couldn't think of anything either. The movements/ideologies that do have strong aesthetics that jump to mind seem to rely heavily on compliance rather than truth seeking, e.g. religions, communism, fascism.

This is sort of a loose reply to your essay. (The things I say about "EA" are just my impressions of the movement as a whole.)

I think that EA has aesthetics, it's just that the (probably not totally conscious) aesthetic value behind them is "lowkeyness" or "minimalism". The Forum and logo seems simple and minimalistically warm, classy, and functional to me.

Your mention of Christianity focuses more on medieval-derived / Catholic elements. Those lean more "thick" and "nationalistic". ("Nationalistic" like "building up a people group that has a deeper emotional identity and shared history", maybe one which can motivate the strongest interpersonal and communitarian bonds). But there are other versions of Christianity, more modern / Protestant / Puritan / desert. Sometimes people are put off by the poor aesthetics of Protestant Christianity, but at some times and in some contexts, people prefer Protestantism over Catholicism, despite its relative aesthetic poverty. I think one set of things that Puritan (and to an extent Protestant), and desert Christianities have in common is self-discipline, work, and frugality. Self-discipline, work, and frugality seem to be a big part of being an EA, or at least in EA as it has been up to now. So maybe in that sense, EA (consciously or not) has exactly the aesthetic it should have.

I think aesthetic lack helps a movement be less "thick" and "nationalistic" and avoiding politics is an EA goal. (EA might like to affect politics, but avoid political identity at the same time.) If you have a "nice looking flag" you might "kill and die" for it. The more developed your identity, the more you feel like you have to engage in "wars" (at least flame wars) over it. I think EA is conflict-averse and wants to avoid politics (maybe it sometimes wants to change politics but not be politically committed? or change politics in the least "stereotypically political" way possible, least "politicized"?). EA favors normative uncertainty and being agnostic about what the good is. So EAs might not want to have more-developed aesthetics, if those aesthetics come with commitments.

I think the EA movement as it is is doing (more or less) the right thing aesthetically. But, the foundational ideas of EA (the things that change people's lives so that they are altruistic in orientation and have a sense that there is work for them to do and that they have to do it "effectively", or maybe that cause them to try to expand their moral circles) are ones that might ought to be exported to other cultures, perhaps to a secular culture that is the "thick" version of EA, or to existing more-"thick" cultures, like the various Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, etc. cultures. A "thick EA" might innovate aesthetically and create a unique (secular, I assume) utopian vision in addition to the numerous other aesthetic/futuristic visions that exist. But "thick EA" would be a different thing than the existing "thin EA".

It seems true that aesthetics provide an extra dimension that can lead to disagreement, conflict, misunderstanding, etc. So I agree that we'd want to be careful about it.

On the other hand that's kind of why so much of everything is bland today, from architecture to politics. Sometimes you do want to present a bold vision that will alienate some people but perhaps rally even more. In a sense, EA already does this (it rallies a certain kind of person and puts off other kinds), and I think adding a layer of good aesthetics would make it possibly more effective at doing that. But it is a risk.

Sick post

What do you think of adopting Enlightment liberal aesthetics more directly (and their classical influences indirectly)

It does seem like an option that is both safe and effective!

I'd be a little bit concerned by this. I think there's a growing sentiment among young people (especially on university campuses) that classicism is aesthetically: regressive, retrograde, old-white-man stuff. Here's a quote from a recent New York Times piece:

"Long revered as the foundation of “Western civilization,” [classics] was trying to shed its self-imposed reputation as an elitist subject overwhelmingly taught and studied by white men. Recently the effort had gained a new sense of urgency: Classics had been embraced by the far right, whose members held up the ancient Greeks and Romans as the originators of so-called white culture. Marchers in Charlottesville, Va., carried flags bearing a symbol of the Roman state; online reactionaries adopted classical pseudonyms; the white-supremacist website Stormfront displayed an image of the Parthenon alongside the tagline “Every month is white history month.”"

Edit: this is a criticism of classicism as a useful aesthetic, not of the enlightenment. Potentially they're severable.

This is very much an online progressives thing, no? In America, the classics are our cultural heritage and carry a lot of respect.

I actually wouldn’t know where to find a liberal student who respects classics (let alone “our cultural heritage”) at my large American university, after four years in the philosophy department!

My comment referred to "America," not liberal university students at top schools. I was making an explicit contrast to "online progressives."

One example is Liv Albert, who loves classical mythology enough to study it in university and create a podcast about it, but she's also super progressive and critical of the ways in which classical myths perpetuated sexism in their day. I think her love for the classics shines through in her podcast. In her own words: "Liv is devoted to the world of Greek and Roman mythology, even if it is full of bloodshed and horrible men."

Thanks for sharing. I'm hesitant about this post's thesis because I think conflating the aesthetic with the political is the reason why so many efforts at improving things fail. People end up supporting policy ideas based on empirical premises that are narratively compelling but wrong. There are many examples, but blank slatism comes to mind. Beyond empirical beliefs, there are broader concepts like tradition, individualism, or nationalism which IMO lack justification for being inherently good, but people have mood-affiliated themselves into worldviews and ideologies built around them anyways because of their intense aesthetic appeal. Mixing up the two also makes for bad aesthetics. There are exceptions but I think most propaganda is bad art.

Even aside from the epistemic effects, I'm not sure cultivating an associated aesthetic style would make effective altruism more persuasive. Some ideas have more aesthetic potential than others. I think effective altruism does not have that much. (I think longtermism has a lot.) You said that effective altruism's lack of a visual aesthetic makes you less interested in it, but a bad visual aesthetic is probably worse than none, no? High modernism's core ideological commitments don't seem insane on their face but someone could reasonably look at a Le Corbusier building and think whatever worldview shares a bed with that can't be right.

In fact, it seems to me like many very successful social and intellectual movements lack a distinct visual aesthetic. Visual symbols and slogans and recurring subject matter, yes. But I can't think of distinct visual styles for, e.g., liberalism, the Civil Rights Movement, the Enlightenment, law and economics, feminism, other stuff.

I'd say that the aesthetics of any movement will exist at some level, and if they're unintentional, they are most likely to be fairly bad (or at least bland if not actively bad) and therefore not provide the benefits I outline.

High modernism is an interesting example — its architectural incarnation was deliberately avoiding highly-developed aesthetics (ornamentation etc.) and the resulting aesthetic is kind of a "default" that most people indeed find unappealing. That has clarified the moral worth of the ideology.

And while it's true that the philosophical movements you name have less defined aesthetics than, say, religions and some political ideologies, I think they all have a degree of intentional aesthetics to them, more so than EA does.

I have wondered "why do we pay for fiction but not for visual art?"

Also I would recommend those who want to make EA art to do it and apply for money and see what happens. I doubt it will be successful unless you are really good but maybe I'm wrong.

A truly great artist could succeed at getting money from EA-aligned orgs, but it indeed seems difficult to do in large part because of the attitudes of the people giving out the money. At least that's my guess.

I love this post! Solarpunk was my first intuition as well, I think there is a lot of good evidence that green and natural environments support happiness and productivity, and so I don’t think it is actually out of alignment with utilitarianism or EA at all.

I have a theory of reality which makes aesthetics the fundamental force of the universe. To demonstrate this, if effective altruism is successful in colonizing space and ends up determining the shape of the future of the universe, then this “shape” will be whatever aesthetic shape we have determined creates maximum utility.

I think aesthetics is a much better fundamental for utilitarianism than pleasure, which intuitively seems quite base and basic. Therefore, I agree that aesthetics are exceedingly important in figuring out what future we want to create.

Aesthetics as the foundation of utilitarianism, rather than pleasure, is definitely an interesting idea. Perhaps less tractable because beauty is much harder to define in a coherent way than physical pleasure, but as you say, the additional complexity might be why it actually matters more.

I'm somewhat conflicted over this. On one hand, I don't agree so much with the sentiment I've heard before that EA needs to work to remain exclusive in some way, and that either it's present asthetic or lack thereof is an important aspect of that.

Part of that fear is the idea that EA thought could be subsumed by wider exposure and sort of dissolve into something only vaguely reminiscent of it's former status. I think we should welcome wider diffusion of EA values. The reasonable side of this fear is that EA "thought leaders" (for want of a better term) could be replaced by less effective ones, that are better at appealing to the masses. While this wouldn't be welcome, I don't think it's likely. At the most there could be a schism, more likely than that, perhaps an uncontentious division would form. Such as with more mainstream academic disciplines, like history or psychology, there could be outlets that appeal to the masses. These don't detract from the competency of the academic or serious amateur. They do I think, make the public slightly more informed on history and psychology. Distracted by misinformation and bad memes, yes, but nevertheless an improvement over nothing. This I think, would be welcome. I could definitely imagine some dangerous memes- Luddite/degrowth reactions to some X risks, apocalypticism generated anomie, typical utilitarian issues, etc. But most EA tenets would remain positive influences: longer term thinking, recognizing the existence of the far future, more concern with X-risks, animal welfare, classic peter singerish generosity, some notion of efficacy in good doing, etc.

Bottom line: we should seek greater proliferation of EA values.

The second part of the common response I identified was to do with the effect of the present asthetic or lack thereof. I do agree that some of it isn't especially invigorating. The EA org light bulb thing is fairly generic. I do think there is something that is an asthetic strong suit with EA though, it's just this- call it "blogcore". Partly as an epistemological consequence of a medium which happens to be common to EAs, and partly because of actual concerted efforts, such as with the blog and creative writing contests, there really is a sort of asthetic there and it really helps the movement gain members and spread EA values. Of course, it's somewhat difficult to separate the medium and it's asthetic, but suffice it to say, the asthetic does transcend the medium somewhat in this case. I think EA should continue to capitalize on this. It gives a nice low cost- high reward aspect to engagement.

Part of an issue I identified with this essay is that it didn't really flesh out what the relationship is between the form of a movement and it's asthethic. For instance take this passage: "Most religions show that it’s an achievable goal. (Incidentally, the lack of inspiring aesthetics may be why New Atheism has mostly failed as a movement, while religions are still doing just fine.)". While there are some secular - religious sort of movements (perhaps the author, singing in a secular choir, may be part of one), to my knowledge, much of "New Atheism" is fairly devoid of original substance and I don't mean that pejoratively. It doesn't aspire to be otherwise, and most New Atheists are adverse to religion as well as gods. Religions have particular aesthetics merely because they are religions. It's determined by the form. EA, via it's various organizations, demographics and particular tenets also has a particular form.

This point may be clearer if we stop thinking about EA as a movement and consider it as an identity. Identities have their particular asthetics. Take hippies for instance. New challenges pop up here, such as dealing with in-out group dynamics. Optimally, the hypothetical identity-sculpter here would have to aim for something not too individuating such that it appeals to too few and divides them from others, but individuating enough, or "thick" enough as James Banks commented, that it succeeds in movement building.

Another, somewhat unrelated comment: the author kinda danced around the idea that surely EAs don't want to give the impression that their goal is "...incrementing a happiness variable, thereby “maximizing utility"! Better avoid that! Perhaps I'm an outlier, but I'm all for that. I'm curious if other people here are any more receptive to the "Higher Pleasures" stuff? I've personally always found the basic Bentham view to have an anti-anthropocentric and depersonalizing consequence which is both philosophically and socially superior.

Loved this post! Thank you for writing and sharing!

I really liked your point about symmetry - if we don't use aesthetics, other movements will, and by not leaning into it and crafting our own aesthetics, they'll be defined haphazardly and incidentally, which we don't want. The Mill + Wordsworth example is also so touching! ❤️

As for the suggestions, classical and solarpunk are both good options (I personally prefer classical), and I'd throw in psychedelic art like Alex Grey's as a contender! 😋

To the points that folks are making in the comments about how much resources should be allocated to aesthetics: art is not something that can be printed en masse like mosquito nets. It wells up and forms organically from the artist, and so we shouldn't push people to create EA-aligned artistic works if they don't feel the desire to do so, otherwise the art will just be lame, canned, or inauthentic.

I'd love to see art, poems, sculptures, songs, and more about / inspired by EA, and I think an improved aesthetic would be a boon to the movement!

Aesthetics are complex. When I was growing up, the impression I had was that Christian aesthetics were seen as old, drab or boring; but these things move in phases, so I'm not surprised that's it's coming back in.

It might be interesting to look at Giving What We Can. It has something of a minimalistic aesthetic as well, whilst also being warmer and more human.

Yeah, I really like GWWC's new design system.

Thanks for writing this! I'm not sure I agree with the conclusion but it was definitely thought-provoking and novel, speaking as someone whose org doesn't even have a logo.

Great piece, I thought. I think Carrick Flynn's loss may in no small part be due to accidentally cultivating a white crypto-bro aesthetic. If that's right, it is a case of aesthetics mattering a fair amount. Personally, I'd like to see EA do more to avoid donning this aesthetic, which anecdotally seems to turn a lot of people off.

Hello Zachary,

I don't think the meaning of aesthetics that Etienne explores in this post really applies to Carrick Flynn's campaign. Aesthetics are a more replicable, cohesive, and norm-driven way of thinking about appearances. Carrick's Campaign may have garnered a poor public perception based on the proximity to/appearances of being a white-crypto bro. However, I don't think this has to do with an aesthetic he cultivated–rather a public image. The aesthetic of the campaign would have been things like graphic design choices, our media selection, and the reliance on green-outdoorsy personal presentation. I worked on the campaign and our aesthetic (scant and innocuous as it was) seemed enormously disconnected from how we were perceived. That suggests a divergence between an intentionally crafted and honed aesthetic and the way that the optics of a campaign and candidate get perceived by the public.

I'm more inspired by the "altruistic" aesthetic than the "effective" aesthetic.

"Effective" blends into the Silicon Valley productivity/efficiency crowd. While there's a lot to appreciate about the Bay Area, I'd prefer not to tie EA to that culture.

On the other hand, there are truly beautiful exemplars of altruism throughout history and around the world.

Personally, I associate altruism with Avalokiteśvara. Art portraying him is colorful and full of details, which, to me, represents that Effective Altruism can bridge all kinds of cultures, theories, and life experiences. Here's why he has so many heads and arms:

I'm gonna need help coming up with more examples of historical altruistic art... Civil rights art from the US? (I love this painting of Harriet Tubman reaching out to the viewer.) Some Christian saints?

Interesting post but not sure I agree with some of your definitions.

"Aesthetics determine how beautiful a thing is, which is simply a specific way of saying how interesting it is. "

Bence Nanay describes Aesthetics in his work as:

So aesthetics is less about a coherent style and more about the reaction to it. In the same sense we can't claim Christianity has a 'richer' aesthetic because some people may react differently based on their culture, experiences, and knowledge about what they see.

I think EA's aesthetic is already emerging in terms of its influence by 20 to 40 year olds who know how to build a functional and well-made website!

Not an easy concept to define, indeed! I have thought a lot about beauty, and to me it is a form of interestingness that emerges from the relationship between a thing and an observer. This seems similar to what you're saying. Aesthetics are never independent of the audience. They also always exist (since people will react to anything), but can be more or less tailored to the audience, which itself can shift.

I didn’t read your post, but I looked at the pictures, and based on that, my guess is that your ideas and perspectives are great.

I think one of the comments missing on “Where’s Today’s Beethoven” was how much of an epic asshole the actual Beethoven was. He was such a pain to deal with and malignantly belligerent down to the smallest things. I suspect this might touch on an answer to what that post was asking.

I really like the some of the references to vaporwave (“nostalgia and longing for a past that never existed”).

My first guess is that it will be deceptively hard for EA to find and get an artist/auteur/vision and execution.

I think it’s deceptively hard to be good at art, sort of like how it’s hard to be good at meta.

My concern is that one of the failure modes will occur:

With great uncertainty, my guess is that one solution is to give (multiple) exploratory commissions to potential artists/designers/architects of this strategy (who will be of very high ability) AND bake in high quality, high insight senior EA supervision in this process.

Then present the solution (with the senior EA fronting/socializing the writing and presenting to EA, not the artist) and then have everyone grit their teeth and do it.

I would strongly support doing this—I have strong roots in the artistic world, and there are many extremely talented artists online that I think could potentially be of value to EA.

Relevant episode of Clearer Thinking

That song! Easily one of my favourites now and I also absolutely love the visual artwork, this aesthetic really speaks to me, thank you 😊

An important example that nobody mentioned is Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality. It seems to me like a very good example of art on rationality and trying to create a better world. I don't know if it is useful to bring other people, but it can serve as a source of motivation, and create a sense of community for people who liked it and can reference it in conversations. I think that stories are very good at that, and I like that as a community we're trying to promote more fictional writings.

On the other hand, I think that it is good that the forum is very clean and minimalist. It is easy to participate in a community in which some members created some stories that you dislike, but it is harder if the "official" aesthetic puts you off.