Abstract

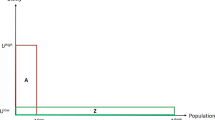

The population ethics literature has long focused on attempts to avoid the repugnant conclusion. We show that a large set of social orderings that are conventionally understood to escape the repugnant conclusion do not in fact avoid it in all instances. As we demonstrate, prior results depend on formal definitions of the repugnant conclusion that exclude some repugnant cases, for reasons inessential to any “repugnance” (or other meaningful normative properties) of the repugnant conclusion. In particular, the literature traditionally formalizes the repugnant conclusion to exclude cases that include an unaffected sub-population. We relax this normatively irrelevant exclusion, and others. Using several more inclusive formalizations of the repugnant conclusion, we then prove that any plausible social ordering implies some instance of the repugnant conclusion. This understanding—that it is impossible to avoid all instances of the repugnant conclusion—is broader than the traditional understanding in the literature that the repugnant conclusion can only be escaped at unappealing theoretical costs. Therefore, the repugnant conclusion provides no methodological guidance for theory or policy-making, because it does not discriminate among candidate social orderings. So escaping the repugnant conclusion should not be a core goal of the population ethics literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

23 April 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01338-7

Notes

For example, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on the repugnant conclusion ends its introductory paragraph with “Thus, the question as to how the Repugnant Conclusion should be dealt with and, more generally, what it shows about the nature of ethics has turned the conclusion into one of the cardinal challenges of modern ethics” (Arrhenius et al. 2017).

For example, Ng (1989) proves that any plausible social ordering must either imply the repugnant conclusion or violate one of two other conditions called Non-Antiegalitarianism and Mere Addition. Similarly, Asheim and Zuber (2014) prove that a family of social orderings “either leads to the Weak Repugnant Conclusion or violates the Weak Non-Sadism Condition.” Other important recent examples are the core contributions of Arrhenius (Population ethics: the challege of future generations (unpublished)) and Bossert (2017) and results in McCarthy et al. (2020).

If lifetime utility is hedonistic, a neutral lifetime utility would be a life that is as good as a life at a limiting case with no experiences.

In the philosophical literature, for example, Temkin Larry (2014) considers denial of the transitive part of Axiom 1, Roberts (2011) denies Axiom 2, and Carlson (On some impossibility theorems in population ethics (forthcoming)) denies Axiom 3. Such issues are a focus of a companion working paper in the philosophy literature (Budolfson and Spears 2018), which does not contain the formal results of this paper.

Parfit (2016) writes of ‘a,’ ‘another,’ ‘this,’ and ‘a version of the’ repugnant conclusion.

Blackorby et al. (1995) use this observation to motivate an additively separable approach to population ethics, on the grounds that the utilities of past people should not influence the evaluation of policies that only impact future people; although our results include non-separable social orderings such as average utilitarianism, we further discuss separability in Sect. 4.3.

Arrhenius (Population ethics: the challege of future generations (unpublished)) uses an equivalent condition called the Strong Quality Addition Principle; Anglin (1977) shows that this principle is implied by both total and average utilitarianism, and Arrhenius extends this proof to Ng’s (1989) variable-value utilitarianism. Note that our theorem below uses a different condition, the unrestricted very repugnant conclusion.

The existence independence axiom holds that for all \(\mathbf {u},\mathbf {v}, \mathbf {w}\in \Omega\), \(\left( \mathbf {u},\mathbf {w}\right) \succsim \left( \mathbf {v},\mathbf {w}\right)\) if and only if \(\mathbf {u}\succsim \mathbf {v}\) (Blackorby et al. 1995, p. 159).

Dasgupta (2005) elaborates: “The Genesis Problem may have been God’s problem, but it is not the problem we face. We are here.”

To see this, consider a case where \(\varepsilon = 10^{-6}\), \(n^\varepsilon = 10,000\), \(u^h = 9\), \(n^h = 10\), and \(\mathbf {v}\) is 10 lives at -10 (for simplicity, let \(n^\ell = 0\)). Average utilitarianism would choose the \(\varepsilon\) lives and total utilitarianism would choose the \(u^h\) lives. If \(\varepsilon = 0\), which would only increase any normative repugnance of such choice, average utilitarianism would continue to choose the \(\varepsilon\) lives as \(n^\varepsilon\) becomes ever larger, but total utilitarianism would continue to choose the \(u^h\) lives.

Gustafsson (2017) offers an example of a social ordering that satisfies Aggregation but not Continuity.

In this paper we distinguish between prioritarianism and egalitarianism using the definitions of Broome (2015). Both functional forms use concave g transformations and same-number risk-free additive separability, but the prioritarian social welfare function is additively separable, while egalitarianism follows (Fleurbaey 2010) in inverting g to use the EDE, so average egalitarianism is \(W^{AE}(\mathbf {u})=g^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{n(\mathbf {u})}\sum _{i = 1}^{n(\mathbf {u})}g(u_i)\right)\) and total egalitarianism is \(W^{TE}(\mathbf {u})= n(\mathbf {u}) g^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{n(\mathbf {u})}\sum _{i = 1}^{n(\mathbf {u})}g(u_i)\right)\). Total prioritarianism satisfies mere addition but total egalitarianism does not; both satisfy the conditions of the Theorem and therefore imply the very repugnant conclusion. Nothing hinges on our use of this terminology from the literature, however.

Broome (2004) advances a case for CLGU which he “standardizes” by setting the critical level equal to zero, adjusting g to match. (In this case, zero may or may not be a neutral life for the person.) Broome interprets his resulting social ordering to imply the repugnant conclusion, which he argues is unintuitive but ultimately acceptable. What Broome there calls “the repugnant conclusion,” Arrhenius (Population ethics: the challege of future generations (unpublished)) names “the weak repugnant conclusion,” a further example of simultaneous debate in the prior literate about the extent and acceptability of the repugnant conclusion.

To our knowledge, we are the first to note these discrepancies or their implications.

To see this, for RDGU, choose y that is very close to x, let \(n=1\) and let \(m>1\). For CLGU let \(c> x> y > 0\) and n be much larger than m (a violation for CLGU of our Axiom 5).

Fleurbaey and Tungodden (2010) prove the incompatibility of their similar Minimal Aggregation and Minimal Non-Aggregation axioms. As the names suggest, their Minimal Aggregation axiom is weaker than our Aggregation axiom. Yet, their Minimal Aggregation and Minimal Non-Aggregation only conflict in the presence of their Reinforcement axiom, which they call a “basic consistency requirement.” However, this is not sufficient to cover all candidates for population ethics because RDGU—which was introduced by Asheim and Zuber (2014) after Fleurbaey and Tungodden’s (2010) theorem—does not satisfy Reinforcement.

This quotation is from a collaboration of 29 authors from economics and philosophy, asking “What should we agree on about the Repugnant Conclusion?”. Further related conclusions include those of Adler (2009) (“Perhaps the best solution, on balance, is to revert to ‘total’ prioritarianism and accept the repugnant conclusion.”) and Cowen (2018) (concluding an appendix about the repugnant conclusion by dismissing its relevance: “I say full steam ahead”).

Our weak sign axioms play a part similar to mere addition (but only apply to perfectly equal populations); our Aggregation axiom has a role similar to Ng’s Non-Antiegalitarianism; and we use an unrestricted repugnant conclusion.

One question is what Parfit himself might have thought of our observation that we misunderstand the lesson of the repugnant conclusion if we impose the normatively irrelevant restriction that \(n(\mathbf {v}) = 0\). Late in his career, in a remarkable final paper, Parfit (2017) wrote about a plurality of related conditions: “such repugnant conclusions” (p. 124) he wrote there, just as also in 2016 he wrote about multiple repugnant conclusions (we cite above). In this final paper, although he still sought to escape the repugnant conclusion, Parfit came to a revised understanding of the repugnant conclusion that resonates with ours: “Because the Repugnant Conclusion seemed to me very implausible, I claimed that we ought to reject this Wide Collective Principle. This claim made two mistakes. We cannot justifiably reject strong arguments merely by claiming that their conclusions are implausible” (p. 154).

References

Adler MD (2009) Future generations: a prioritarian view. George Wash Law Rev 77(5/6):1478

Anglin B (1977) The repugnant conclusion. Can J Philos 7(4):745–754

Arrhenius G (n.d.) Population ethics: the challenge of future generations. (unpublished typescript, July 2017)

Arrhenius G (2000) An impossibility theorem for welfarist axiologies. Econ Philos 16(2):247–266

Arrhenius G (2003) The very repugnant conclusion. Uppsala Philosophical Studies, p 51

Arrhenius G, Ryberg J, Tännsjö T (2017) The repugnant conclusion. In: Zalta EN (ed) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford University, Spring 2017 edition

Asheim GB, Zuber S (2014) Escaping the repugnant conclusion: rank-discounted utilitarianism with variable population. Theor Econ 9(3):629–650

Asheim GB, Zuber S (2018) Rank-discounting as a resolution to a dilemma in population ethics. Working paper, University of Oslo and PSE

Blackorby C, Donaldson D (1984) Social criteria for evaluating population change. J Public Econ 25(1–2):13–33

Blackorby C, Bossert W, Donaldson D (1995) Intertemporal population ethics: critical-level utilitarian principles. Econometrica 63(6):1303–1320

Blackorby C, Bossert W, Donaldson D, Fleurbaey M (1998a) Critical levels and the (reverse) repugnant conclusion. J Econ 67(1):1–15

Blackorby C, Primont D, Russell RR (1998b) Separability: a survey. Handb Util Theory 1:49–92

Blackorby C, Bossert W, Donaldson DJ (2005) Population issues in social choice theory, welfare economics, and ethics. Cambridge University Press

Bossert W (2017) Anonymous welfarism, critical-level principles, and the repugnant and sadistic conclusions. Working paper, University of Montréal

Boucekkine R, Fabbri G (2013) Assessing Parfit’s repugnant conclusion within a canonical endogenous growth set-up. J Popul Econ 26(2):751–767

Broome J (2004) Weighing lives. Oxford UP, Oxford

Broome J (2012) Climate matters: ethics in a warming world (Norton global ethics series). WW Norton & Company

Broome J (2015) Equality versus priority: a useful distinction. Econ Philos 31(2):219–228

Budolfson M, Spears D (2018) Why the repugnant conclusion is inescapable. Working paper, Princeton University CFI

Carlson E (forthcoming) On some impossibility theorems in population ethics. In: Campbell T et al (ed) The Oxford handbook of population ethics. Oxford

Cowen T (1996) What do we learn from the repugnant conclusion? Ethics 106(4):754–775

Cowen T (2018) Stubborn attachments. Stripe Press

Dasgupta P (2005) Regarding optimum population. J Polit Philos 13(4):414–442

Dasgupta P (2016) Birth and death. Working paper 2016/19, Cambridge-INET

Deschamps R, Gevers L (1977) Separability, risk-bearing, and social welfare judgements. Eur Econ Rev 10(1):77–94

Fleurbaey M (2010) Assessing risky social situations. J Polit Econ 118(4):649–680

Fleurbaey M, Tungodden B (2010) The tyranny of non-aggregation versus the tyranny of aggregation in social choices: a real dilemma. Econ Theory 44(3):399–414

Fleurbaey M, Zuber S (2015) Discounting, beyond utilitarianism. Economics 9(2015–12):1–52

Franz N, Spears D (2020) Mere addition is equivalent to avoiding the sadistic conclusion in all plausible variable-population social orderings. Econ Lett 196:109547

Gustafsson JE (2017) Moral aggregation, by Iwao Hirose. Mind 126(503):964–967

Hurka T (1983) Value and population size. Ethics 93(3):496–507

Lawson N, Spears D (2018) Optimal population and exhaustible resource constraints. J Popul Econ 31(1):295–335

McCarthy D, Mikkola K, Thomas T (2020) Utilitarianism with and without expected utility. J Math Econ. 87:77–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmateco.2020.01.001

Nerlove M, Razin A, Sadka E (1982) Population size and the social welfare functions of Bentham and Mill. Econ Lett 10(1–2):61–64

Ng Y-K (1989) What should we do about future generations?: impossibility of Parfit’s theory X. Econ Philos 5(2):235–253

Palivos T, Yip CK (1993) Optimal population size and endogenous growth. Econ Lett 41(1):107–110

Parfit D (1984) Reasons and persons. Oxford UP, Oxford

Parfit D (2016) Can we avoid the repugnant conclusion? Theoria 82(2):110–127

Parfit D (2017) Future people, the non-identity problem, and person-affecting principles. Philos Public Aff 45(2):118–157

Pivato M (2020) Rank-additive population ethics. Econ Theory 69:861–918

Roberts MA (2011) The asymmetry: a solution. Theoria 77:333–367

Scovronick N, Budolfson MB, Dennig F, Fleurbaey M, Siebert A, Socolow RH, Spears D, Wagner F (2017) Impact of population growth and population ethics on climate change mitigation policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(46):12338–12343

Sider TR (1991) Might theory X be a theory of diminishing marginal value? Analysis 51(4):265–271

Spears D (2017) Making people happy or making happy people? Questionnaire-experimental studies of population ethics and policy. Soc Choice Welf 1–25

Temkin LS (2014) Rethinking the good: moral ideals and the nature of practical reasoning. Oxford University Press

Zuber S, Asheim GB (2012) Justifying social discounting: the rank-discounted utilitarian approach. J Econ Theory 147(4):1572–1601

Zuber S, Venkatesh N, Tännsjö T, Tarsney C, Orri SH, Steele K, Spears D, Sebo J, Pivato M, Ord T, Ng Y-K, Masny M, MacAskill W, Lawson N, Kuruc K, Hutchinson M, Gustafsson JE, Greaves H, Forsberg L, Fleurbaey M, Coffey D, Cato S, Castro C, Campbell T, Budolfson M, Broome J, Berger A, Beckstead N, Asheim GB (2021) What should we agree on about the repugnant conclusion?. Utilitas. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095382082100011Xgg

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper received no specific funding, Spears’ research is supported by grant K01HD098313 and by P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The original online version of this article was revised: Due to incorrect affiliations of the second author. Now, they have been corrected.

Appendices

Appendix

Proofs

2.1 Proof of Theorem 1

The proof uses Aggregation twice. If \(\succsim\) satisfies Axiom 5, then choose \(\nu \in (0,\varepsilon )\); this will be used to construct a \(\mathbf {v}\) without negative lives. If \(\succsim\) satisfies Axiom 6 but not Axiom 5, choose \(\nu < 0\), which implies \(\nu < \varepsilon\). Choose \(\delta \in (0, \min (\frac{\varepsilon - \nu }{3}, \frac{\varepsilon }{3}))\) and, if \(\nu <0\), \(\delta < -\nu\). For any m, construct \(\left( u^h\mathbf {1}_{n^h} , \nu \mathbf {1}_m \right)\); if m is large enough then \((\nu + \delta ) \mathbf {1}_{n^h+m} \succ \left( u^h\mathbf {1}_{n^h} , \nu \mathbf {1}_m \right)\), by Aggregation. For any \(n^\varepsilon\), construct \(\left( \varepsilon \mathbf {1}_{n^\varepsilon }, u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{n^\ell } , \nu \mathbf {1}_m\right)\); if \(n^\varepsilon\) is large enough (once m is fixed) then \(\left( \varepsilon \mathbf {1}_{n^\varepsilon }, u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{n^\ell } , \nu \mathbf {1}_m\right) \succ (\varepsilon - \delta ) \mathbf {1}_{n^\varepsilon + n^\ell +m}\). Choose m large enough to satisfy Aggregation; then choose \(n^\varepsilon\) large enough to satisfy Aggregation and such that \(n^\varepsilon + n^\ell +m > n^h+m\). By one of the sign axioms and by the construction of \(\delta\), \((\varepsilon - \delta ) \mathbf {1}_{n^\varepsilon + n^\ell +m} \succ (\nu + \delta ) \mathbf {1}_{n^h+m}\). Then by applying transitivity twice, \(\left( \varepsilon \mathbf {1}_{n^\varepsilon }, u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{n^\ell } , \nu \mathbf {1}_m\right) \succ \left( u^h\mathbf {1}_{n^h} , \nu \mathbf {1}_m \right)\).

2.2 Proof of Proposition 1

Because the extended very repugnant conclusion implies the very repugnant conclusion, the proof of Theorem 1 applies for orderings that satisfy Aggregation and a sign axiom.

For social orderings that satisfy Aggregation but not a zero axiom, or for social orderings that merely satisfy Minimal Equality Preference, the proof by construction uses the \(u_j = v_j + \varepsilon\) horn of the definition of \(\varepsilon\)-change. For Aggregation-satisfying orderings, simply include a very large base population; improve many lives by \(\varepsilon\).

To begin a construction for Non-Aggregation social orderings, choose any \(\varepsilon\), \(u^\ell\), \(u^h\), \(n^\ell\), and \(n^h\) according to the Extended VRC. Next, set \(m^h\) and \(m^\ell\) in the EVRC to both be the maximum of \(n^h +1\) and \(n^\ell + 1\). Then, let \(\xi\) in the Axiom be \(u^\ell - \varepsilon\) from the EVRC. Let \(\delta\) in the axiom be \(\varepsilon\) from the EVRC. Notice that \(\xi + \delta\) in the Axiom now equals \(u^\ell\) from the EVRC. Now, let \(\mathbf {u}\) from the Axiom be \(u^h \mathbf {1}_{m^h}\). Notice that \(n(\mathbf {u})\) from the Axiom is now fixed at \(n(\mathbf {u})=m^h=m^\ell\) from the EVRC.

The construction next uses the Minimal Equality Preference axiom. We have now specified a \(\mathbf {u}\), \(\xi\), and \(\delta\). So there exists an \(n^*\) such that if \(n>n^*\) then \((\xi + \delta )\mathbf {1}_{n + n(\mathbf {u})} \succ \left( \xi \mathbf {1}_{n} , \mathbf { u} \right)\). Choose such an n and call it \(\tilde{n}\). This construction fulfills the conditions of the Extended VRC. Note that we may choose any \(\mathbf {v} \in \Omega\). Let \(\mathbf {v} = \xi \mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}}\). Now notice that \(\left( \xi \mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}} , \mathbf { u} \right)\) from the Axiom is \(\left( \xi \mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}} , u^h \mathbf {1}_{m^h}\right)\), which is \(\left( \mathbf {v} , u^h \mathbf {1}_{m^h}\right) = \mathbf {v}^h\) from the EVRC. Let \(\mathbf {v}^\ell = (\xi + \delta )\mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n} + n(\mathbf {u})}=(\xi + \delta )\mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n} + m^\ell }=\left( u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}} , u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{m^\ell }\right) =\left( (\xi + \varepsilon )\mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}} , u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{m^\ell }\right)\). Set \(n^\varepsilon\) equal to \(\tilde{n}\). Finally, we can see that \(\left( (\xi + \varepsilon )\mathbf {1}_{\tilde{n}} , u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{m^\ell }\right)\) is separated by \(n^\varepsilon\) \(\varepsilon\)-changes from \(\left( \mathbf {v} , u^\ell \mathbf {1}_{m^\ell }\right)\).

Maximin and maximax both can be shown to imply the extended very repugnant conclusion by having \(\mathbf {v}\) contain the least or greatest (respectively) utility level, and then increasing this with one \(\varepsilon\)-change.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spears, D., Budolfson, M. Repugnant conclusions. Soc Choice Welf 57, 567–588 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01321-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-021-01321-2