A flaw in a simple version of worldview diversification

Summary

I consider a simple version of “worldview diversification”: allocating a set amount of money per cause area per year. I explain in probably too much detail how that setup leads to inconsistent relative values from year to year and from cause area to cause area. This implies that there might be Pareto improvements, i.e., moves that you could make that will result in strictly better outcomes. However, identifying those Pareto improvements wouldn’t be trivial, and would probably require more investment into estimation and cross-area comparison capabilities.1

More elaborate versions of worldview diversification are probably able to fix this flaw, for example by instituting trading between the different worldview—thought that trading does ultimately have to happen. However, I view those solutions as hacks, and I suspect that the problem I outline in this post is indicative of deeper problems with the overall approach of worldview diversification.

This post could have been part of a larger review of EA (Effective Altruism) in general and Open Philanthropy in particular. I sent a grant request to the EA Infrastructure Fund on that topic, but alas it doesn’t to be materializing, so that’s probably not happening.

The main flaw: inconsistent relative values

This section perhaps has too much detail to arrive at a fairly intuitive point. I thought this was worth doing because I find the point that there is a possible Pareto improvement on the table a powerful argument, and I didn’t want to hand-wave it. But the reader might want to skip to the next sections after getting the gist.

Deducing bounds for relative values from revealed preferences

Suppose that you order the ex-ante values of grants in different cause areas. The areas could be global health and development, animal welfare, speculative long-termism, etc. Their values could be given in QALYs (quality-adjusted life-years), sentience-adjusted QALYs, expected reduction in existential risk, but also in some relative unit2.

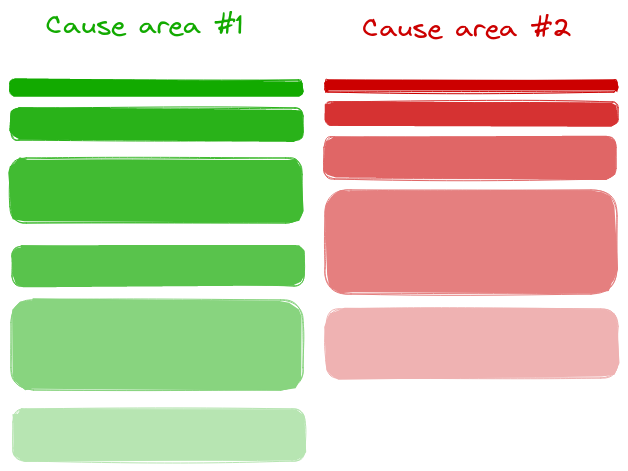

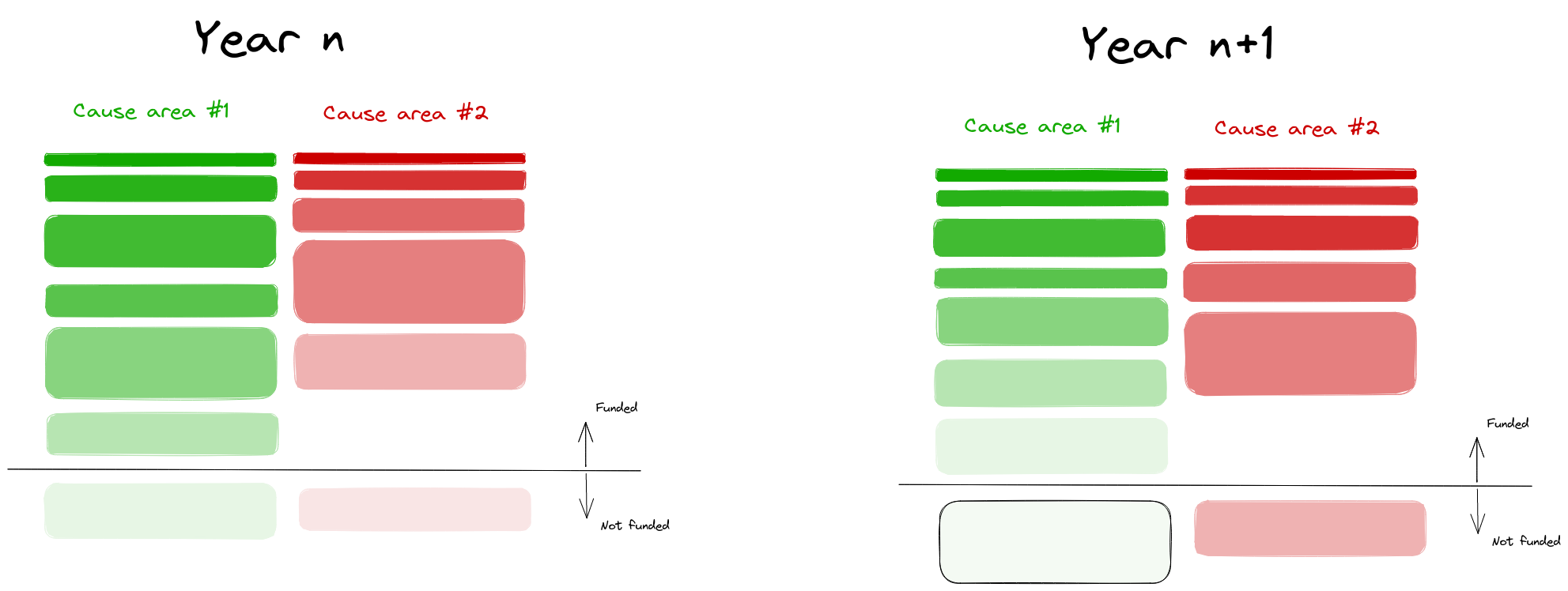

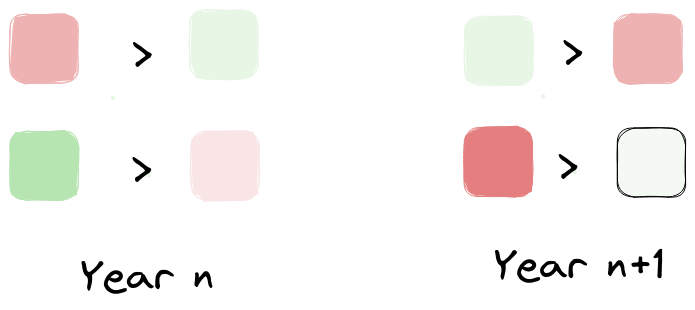

For simplicity, let us just pick the case where there are two cause areas:

More undilluted shades represent more valuable grants (e.g., larger reductions per dollar: of human suffering, animal suffering or existential risk), and lighter shades represent less valuable grants. Due to diminishing marginal returns, I’ve drawn the most valuable grants as smaller, though this doesn’t particularly matter.

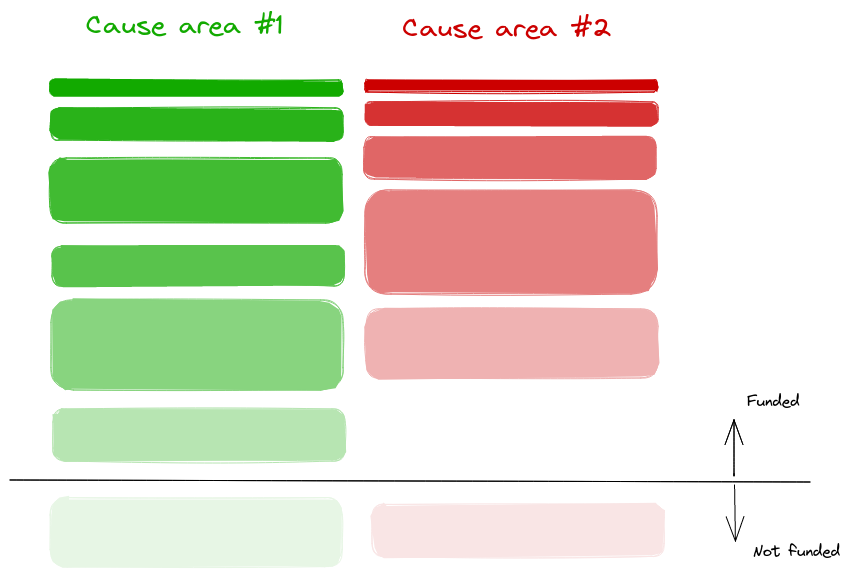

Now, we can augment the picture by also considering the marginal grants which didn’t get funded.

In particular, imagine that the marginal grant which didn’t get funded for cause #1 has the same size as the marginal grant that did get funded for cause #2 (this doesn’t affect the thrust of the argument, it just makes it more apparent):

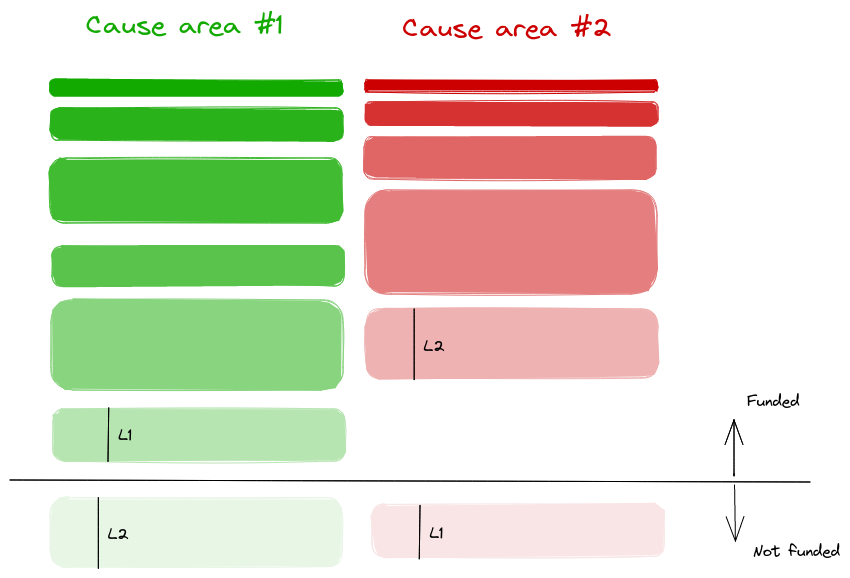

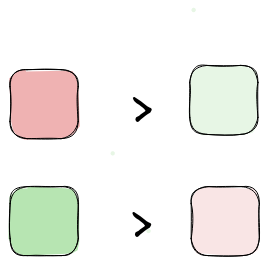

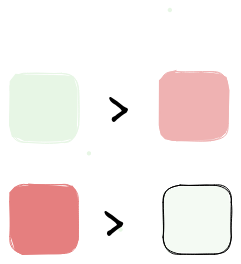

Now, from this, we can deduce some bounds on relative values:

In words rather than in shades of colour, this would be:

- Spending L1 dollars at cost-effectiveness A greens/$ is better than spending L1 dollars at cost-effectiveness B reds/$

- Spending L2 dollars at cost-effectiveness X reds/$ is better than spending L2 dollars at cost-effectiveness Y greens/$

Or, dividing by L1 and L2,

- A greens is better than B reds

- X reds is better than Y reds

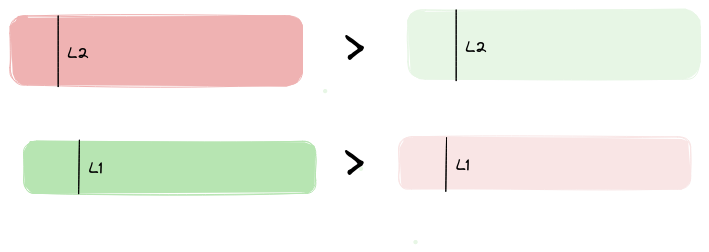

In colors, this would correspond to all four squares having the same size:

Giving some values, this could be:

- 10 greens is better than 2 reds

- 3 reds is better than 5 greens

From this we could deduce that 6 reds > 10 greens > 2 reds, or that one green is worth between 0.2 and 0.6 reds.

But now there comes a new year

But the above was for one year. Now comes another year, with its own set of grants. But we are keeping the amount we allocate to each area constant.

It’s been a less promising year for green, and a more promising year for red, . So this means that some of the stuff that wasn’t funded last year for green is funded now, and some of the stuff that was funded last year for red isn’t funded now:

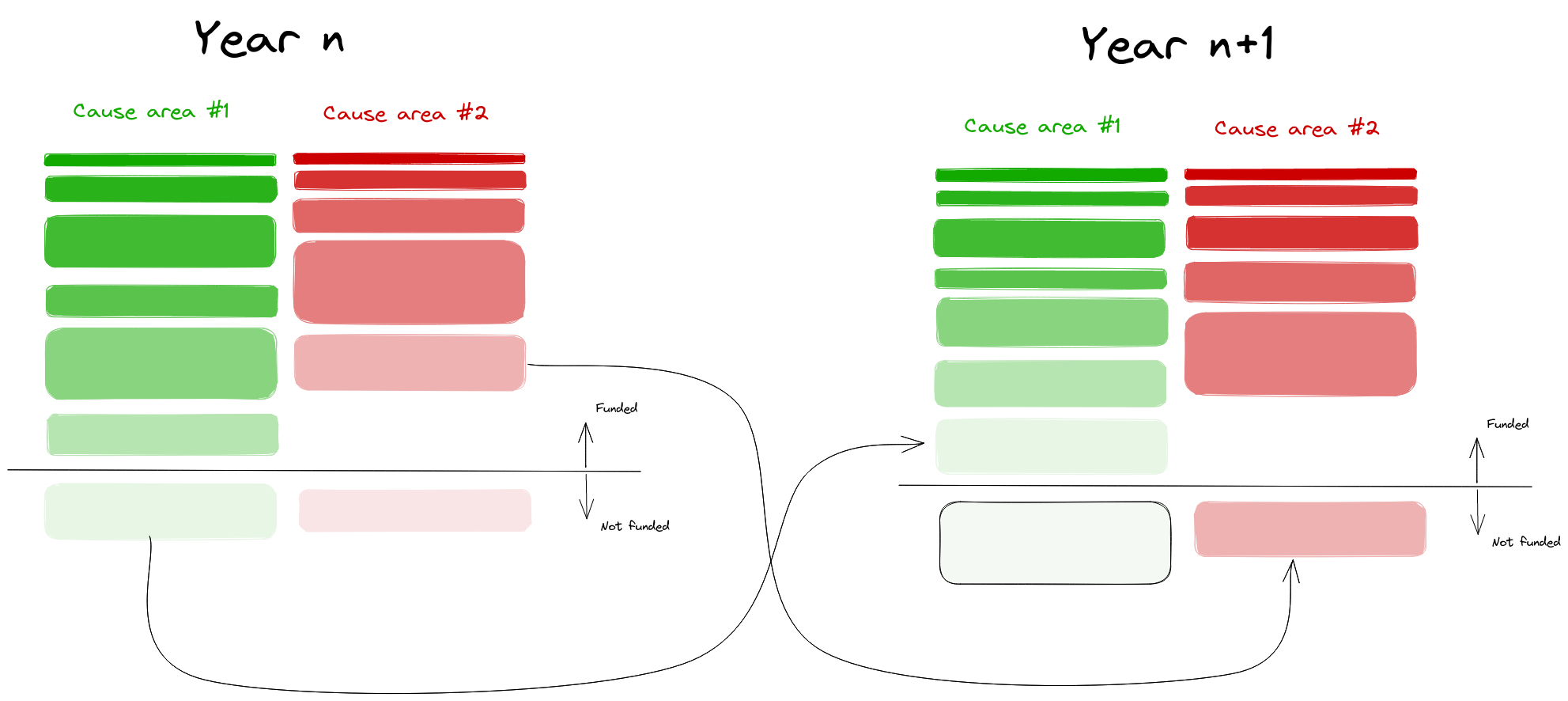

Now we can do the same comparisons as the last time:

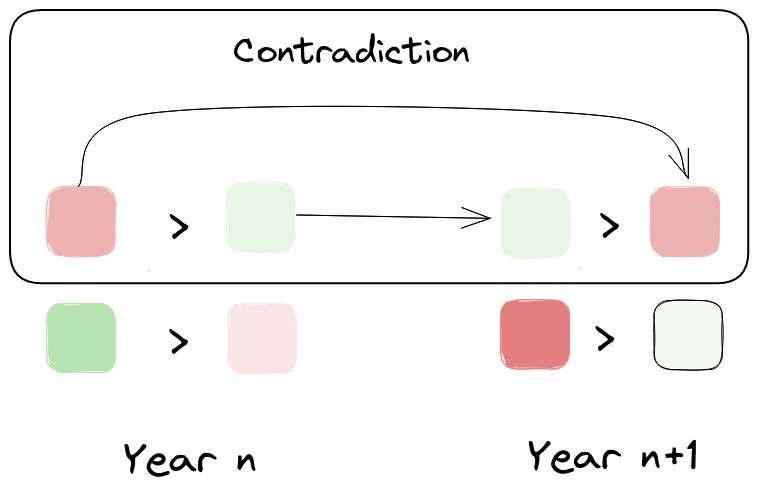

And when we compare them against the previous year

we notice that there is an inconsistency.

Why is the above a problem

The above is a problem not only because there is an inconsistency, but because there is a possible pareto improvement that’s not taken: transfer funding from cause area #2 to cause #1 in the first year, and viceversa in year #2, and you will get both more green and more red.

With this in mind, we can review some alternatives.

Review of alternatives

Keep a “moral parliament” approach, but allow for trades in funding.

Worldview diversification might stem from a moral-parliament style set of values, where one’s values aren’t best modelled as a unitary agent, but rather as a parliament of diverse agents. And yet, the pareto improvement argument still binds. A solution might be to start with a moral parliament, but allow trades in funding from different constituents of the parliament. More generally, one might imagine that given a parliament, that parliament might choose to become a unitary agent, and adopt a fixed, prenegotiated exchange rate between red and green.

One problem with this approach is that the relative values arrived at through negotiation will be “dangling”, i.e., they will depend on arbitrary features of the world, like each sides' negotiating position, negotiation prowess, or hard-headedness.

I suspect that between:

- asking oneself how much one values outcomes in different cause areas relative to each other, and then pursuing a measure of aggregate value with more or less vigor

- dividing one’s funding and letting the different sides negotiate it out.

it’s very possible that a funder’s preferences would be best satisfied by the first option.

Calculate and equalize relative values

Alternatively, worldview diversification can be understood as an attempt to approximate expected value given a limited ability to estimate relative values. If so, then the answer might be to notice that worldview-diversification is a fairly imperfect approximation to any kind of utilitarian/consequentialist expected value maximization, and to try to more perfectly approximate utilitarian/consequentialist expected value maximization. This would involve estimating the relative values of projects in different areas, and attempting to equalize marginal values across cause areas and across years.

Note that there is a related but slightly different question of how harcore one should be in one’s optimization. The question is related, but I think I can imagine an arrangement where one does a somewhat chill type of optimization—for example by adding deontological constraints to one’s actions, like not doing fraud—and still strive to take all possible Pareto improvements in one’s choices.

As this relates to the Effective Altruism social movement and to Open Philanthropy (a large foundation)

Open Philanthropy is a large foundation which is implementing a scheme similar in spirit to—but probably more sophisticated than—the simple version of worldview diversification that I outlined here. Honestly, I have little insight into the inner workings of Open Philanthropy, and I wrote this post mostly because I was annoyed, and less in the expectation of having an impact.

Still, here are two quotes from this 2017 blogposts which suggests that Open Philanthopy fell prey to the problem of inconsistent relative values:

A notable outcome of the framework we’re working on is that we will no longer have a single “benchmark” for giving now vs. later, as we did in the past. Rather, each bucket of capital will have its own standards and way of assessing grants to determine whether they qualify for drawing down the capital in that bucket. For example, there might be one bucket that aims to maximize impact according to a long-termist worldview, and another that aims to maximize impact according to a near-termist worldview; each would have different benchmarks and other criteria for deciding on whether to make a given grant or save the money for later. We think this approach is a natural outcome of worldview diversification, and will help us establish more systematic benchmarks than we currently have.

We see a great deal of intuitive appeal in the following principle, which we’ll call the “outlier opportunities” principle:

if we see an opportunity to do a huge, and in some sense “unusual” or “outlier,” amount of good according to worldview A by sacrificing a relatively modest, and in some sense “common” or “normal,” amount of good according to worldview B, we should do so (presuming that we consider both worldview A and worldview B highly plausible and reasonable and have deep uncertainty between them).

I think that is inelegant and could be better solved through inter-cause-area relative values.

Effective Altruism is a social movement nominally about “using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis”. It is related but distinct from Open Philanthropy. Here is a recent post from a community member arguing that decisions should not be made by pursuing “expected choiceworthiness”, but rather:

The sortition model prescribes that if you have x% credence in a theory, then you follow that theory x% of cases. If you have 20% credence in Kantianism, 30% credence in virtue ethics and 50% credence in utilitarianism, you follow Kantianism 20% of the time, virtue ethics 30% of the time and utilitarianism 50% of the time. When you act according to a theory is selected randomly with the probability of selection being the same as your credence in said theory.

It seems to me that a scheme such as this also falls prey to the problem of inconsistent relative values.

People in the Effective Altruism Movement also face the problem of trading off near-term altruistic goods—like quality-adjusted life years from global health interventions—against some chance of a larger but more speculative outcome, classically avoiding human extinction. I will relegate most discussion of this point to a footnote, but in short, if you don’t have consistent relative values between long-term and short-term interventions, then there will also be untaken Pareto improvements3.

Challenges and recommendations

Throughout this point, I have assumed that we can estimate:

- the ex-ante value of different grants and options

- the relative values of progress across different cause areas

The problem with this is that this is currently not possible. My impression is that estimation:

- is pretty advanced for global health and development and adjacent cause areas

- is nascent for animal welfare and suffering

- is very rudimentary for speculative longtermism cause areas

My recommendation here would be to invest more in relative value estimation across cause areas. Here is some past work on steps one would have to carry out to arrive at good relative estimates.

The organization that I work for—the Quantified Uncertainty Research Institute—is doing some work on this topic, and we should be putting out a few blogposts in the near future. Others like Rethink Priorities, are also working on similar or very adjacent topics, as reviewed here.

-

This could mean that, taking into account the cost of estimation, the improvements are no longer Pareto improvements, or even pareto improvements. For instance, it could be that for all cause areas,

- I.e., you could ask about how much you value each project compared to each other, as I previously explored here.↩

-

Note that, in a sense, the relative value between b QALYs and a few basis points in existential risk reduction is epsilon:1, or 1:~infinity. This is because one basis points contains many many QALYs.

But in another sense, even if you have a really high intrinsic discount rate and value QALYs a lot, for the mother of god let there be no pareto improvements, let the relative values be consistent.

In practice, though, you aren’t comparing q QALYs against b basis points, you are comparing q QALYs against some amount of quality-adjusted speculative work, which corresponds to a really hard to estimate amount, which could possibly be 0 or negative, in terms of basis points of existential risk reduction. So the point about the ratio between QALYs and existential risk being epsilon:1 becomes less apparent, and possibly just not the case. But the argument that there shouldn’t be Pareto improvements still applies.↩

7 Comments

I liked the outlining+visualizations here, seems good to continuously suggest improvements.

On Open Philanthropy's position, it seems a lot to me like you're partially recommending efficient trade procedures between groups at OP.

Trade mechanisms do increase efficiency (trade is great), but it can take some cost to set up and manage. If I were in charge of OP, I imagine I'd have a long list of improvements I'd be working on, and it's not clear where something like this would fall.

On the other extreme to OP was the FTX regranting system, where there were tons of mini budgets - I'm sure there were a ton of similar inefficiencies there, but at the same time, I think that was an interesting experiment.

My impression is that there are tons of room for optimizations when it comes to funders (for example, I'd be curious to see more trade between the main EA funders), but at the same time, they have a lot of of stuff to do per person, and also perhaps much bigger optimizations to focus on.

> On Open Philanthropy's position, it seems a lot to me like you're partially recommending efficient trade procedures between groups at OP.

I think that would solve this specific problem, but as mentioned in the post, I think it would still leave cross-cause relative values as "dangling", or "untethered", i.e., they would not necessarily correspond to my (or to Rethink Priorities') relative values for a human vs a given species of animals. So sure, I think that they would be an improvement, but my preferred approach would be to go full relative values.

On how much optimization to do per person, yeah, we disagree here. I think that at the point when they spend $200M on criminal justice reform instead of on global health, these kinds of considerations are already indicative that a lot of value is being left on the table.

Hi Nuño,

I'm the person that created the sortition approach to moral uncertainty that you mentioned here. I think that if you have only qualitative measures (which the 'runoff approach' allows) this issue doesn't arise, but you also don't have a ratio to compare so it's not a useful tool in worldview diversification anyway. If you want a ratio the convex approach works, but that also creates inconsistencies over time.

The thing is, I put those in there deliberately. By having a chance you fulfill one value one year and another the next year you are protecting minority positions. If we imagine a parliament where one party has 51% of the vote, they have 100% of the power. But if you have a random element (e.g. a random ballot) the power is proportionally distributed. The parliament acting 'inconsistent' is a sacrifice to protect minority positions. Now my preferred interventions are a little bit more complex than random ballots, but I hope this simple example shows why I opted to put random elements in my theory.

If you don't want randomization you can take the 'centroid approach', but this probably has the same issue you outlined in your post.

I'm the person that created the sortition approach to moral uncertainty that you mentioned here. I think that if you have only qualitative measures (which the 'runoff approach' allows) this issue doesn't arise, but you also don't have a ratio to compare so it's not a useful tool in worldview diversification anyway. If you want a ratio the convex approach works, but that also creates inconsistencies over time.

I find this paragraph a bit confusing. You are mentioning "sortition approach", a "runoff approach", a "convex approach", but it's not clear to me what these are refering to. Could you be a bit more explicit and elaborate so that we can communicate a bit better?

if you have only qualitative measures (which the 'runoff approach' allows) this issue doesn't arise, but you also don't have a ratio to compare so it's not a useful tool in worldview diversification anyway

I don't know whether the bolded "it" refers to the ratio or to the issue, and I am differently confused depending on which of those it refers to :), could you clarify?

"I don't know whether the bolded "it" refers" The 'it' referred to having only qualitative measures. Not very useful if you want to have a cardinal (or ordinal) scale of the priority of interventions.

"Could you be a bit more explicit and elaborate so that we can communicate a bit better?" Yes. The 'sortition approach' is the simplest version of using randomization, this is what you quoted. The (EA) post then has a paragraph titled "runoff randomization" which outlines a slightly more complex approach (runoff approach). The post then has a paragraph titled "convex randomization" which describes the 'convex approach'. I will copypaste the explanation for that approach here (but there's a visual explanation in the post itself, which will probably help):

Order the options in an arbitrary way from 1 to k.

For each theory Z, let V(Z) be the list of choice-worthinesses of all options according to this theory. I.e., the first entry is Z’s evaluation of option 1, the last entry is Z’s evaluation of option k.

Interpret the entries in the list V(Z) as the coordinates of a point in a k-dimensional space.

Let P be the set of all these points, one for each theory.

Let H be the “convex hull” of the set of points P, i.e., all points contained in a tight rubber envelope around P, or, more mathematically, all points that lie on some straight line between any two points in P.

Let R be a randomly chosen point in the interior of H (i.e., in H but not on the boundary of H), chosen from the uniform distribution on H. (Note that by excluding the boundary, we in particular exclude the possibility that R equals any of the original points in P.)

Choose the option that corresponds to the largest entry in R. I.e., if the third entry in R is the largest, choose the third option.

Oh, I see, you were mentioning this post. Sorry I didn't catch this sooner, most of my beef is with Open Philanthropy.

From my perspective the approaches you cover are unnecessarily convoluted. I can see how this would make sense if you have advanced cases of the human heart in conflict with itself, or of a house divided against itself. But if not, the downsides (intertemporal inconsistency, pushing for one thing one year and for another thing the next year, rather than for a compromise the whole time) just seem too large in comparison, particularly since you have the option of becoming more vNM-rational.

In particular:

If you have 20% credence in Kantianism, 30% credence in virtue ethics and 50% credence in utilitarianism, you follow Kantianism 20% of the time, virtue ethics 30% of the time and utilitarianism 50% of the time. When you act according to a theory is selected randomly with the probability of selection being the same as your credence in said theory.

then when the nazis knock on your door asking whether you are hiding any jews, you will lie when a utilitarian and would not lie when a Kantian (arguendo), so the nazis just have to keep trying. Is this what you are advocating? Convex randomization, which seems like the cooler approach on your post, seems like it would still have this problem, is that correct? I'm also unclear about whether the centroid approach fixes this issue.

Or are you advocating a version where you roll the dice and then henceforth always act according to one moral theory? That does have the problem that some moral theories don't care that much about some events, as you mention, so you are losing gains from trade.

So given that, it just seems more parsimonious to push towards comparability, i.e., try to design a vNM-rational policy that closely approximates your values, resolving contradictions when they exist.

For another example, if you have an "altruistic part" of yourself that cares about being vegetarian, and a "selfish part" that enjoys eating meat, it seems kind of interesting that you'd only be vegetarian half the time, though I guess I do see the appeal. I think my preferred approach would be to try to quantify the value of different animals, as in here, and then come to a single decision about whether you care about the taste more than you care about the expected years of animal suffering for different types of food. Creating that estimate would take effort, though.

Anyways, I think I'm being a bit rambly here, sorry about that.

Btw, you might be interested in Scott Garrabant's posts on a closely related topic, starting here.

I envisioned you deciding on a policy of whether or not to lie to nazi's as one decision and staying consistent within that policy. Which is only a partial solution since you run into a version of the reference class problem: if non-nazi antisemitists now come knocking, is that different enough to reroll those dice? Plausibly you could have a consistent theory of reference classes, but many people might have different theories for when to reroll, which makes cooperation harder. (Randomization also helps against pascals mugging, but not by much.)

With a centroid approach you are always consistent and I think it is the strongest approach iff you believe in intertheoretic comparisons of value and ratio-scale measurability. The 'trade' is happening in the theory, but for trade you need quantification and a single unit, so if you think some moral theories are qualitative or incomparable you won't find the centroid approach appealing (although I did mention a version that converts qualitative assessments into quantitative ones, but that has other drawbacks).

I think people from the EA community (who are very into reducing everything to single quantifiable units) will tend to like the centroid approach more, whereas people with a background in more continental philosophy will tend to like the runoff approach more.

Thanks for the link, I'll check that out.