Jason

Bio

I am an attorney in a public-sector position not associated with EA, although I cannot provide legal advice to anyone. My involvement with EA so far has been mostly limited so far to writing checks to GiveWell and other effective charities in the Global Health space, as well as some independent reading. I have occasionally read the forum and was looking for ideas for year-end giving when the whole FTX business exploded . . .

How I can help others

As someone who isn't deep in EA culture (at least at the time of writing), I may be able to offer a perspective on how the broader group of people with sympathies toward EA ideas might react to certain things. I'll probably make some errors that would be obvious to other people, but sometimes a fresh set of eyes can help bring a different perspective.

Posts 3

Comments2333

Topic contributions2

I believe this applies only to stock that has appreciated in value, right? If you have losers, you want to take the capital loss (either to offset your capital gains, or to reduce your other income by up to $3,000 with carryover available).

There's an argument for some people to buy stock to donate. Those of us who bunch their donations to maximize deductibility should probably be buying a variety of somewhat volatile stocks during our off years, donating the winners either directly or through a DAF during our giving years, and selling the losers to harvest the losses whenever appropriate. (Just remember to avoid creating a wash sale!)

If you're in the US and dropping checks in the mail today, I would not rely on the assumption that they would be postmarked today. Effective December 24, the postmark date is no longer the date on which mail is deposited with USPS (although it sounds like postmark date may not have been fully reliable even before this policy change).

Under Treasury Regulation 1.170A-1, "[t]he unconditional delivery or mailing of a check which subsequently clears in due course will constitute an effective contribution on the date of delivery or

mailing." I have usually filmed myself dropping checks into the USPS mailbox for this reason, and will do so with my wife's charitable contributions this year (mine are already done). The safer alternative, especially if large sums are involved, would be to take the mailpiece to a post office and have a manual postmark applied by the person behind the counter (or send via certified mail).

I'm initially skeptical on tractability -- at least of an outright ban, although maybe I am applying too much of a US perspective. Presumably most adults who indulge in indoor tanning know that it's bad for you. There's no clear addictive process (e.g., smoking), third-party harms (e.g., alcohol), or difficulty avoiding the harm -- factors which mitigate the paternalism objection when bans or restrictions on other dangerous activities are proposed.

Moreover, slightly less than half of US states even ban all minors from using tanning beds, and society is more willing to support paternalistic bans for minors. That makes me question how politically viable a ban for adults would be. "[T]he indoor tanning lobby" may not be very powerful, but it would be fighting for its very existence, and it would have the support of its consumers.

On the other side of the equation, the benefits don't strike me as obviously large in size. Most skin-cancer mortality comes from melanomas (8,430/year in the US), but if I am reading this correctly then only 6,200 of the 212,200 melanomas in the US each year are attributed to indoor tanning. The average five-year survival for melanoma in the US is 94%. So the number of lives saved may not be particularly high here.

If you’re taking the standard deduction (ie donating <~$15k)

The i.e. here is too narrow -- the criterion is whether the person will have enough itemized deductions of any sort to make itemizing worthwhile vs. the standard deduction of $15,750 (for a single person). Almost everyone will have state and local taxes to count; many of us have mortgage interest to potentially itemize as well.

If the reader knows they are going to take the standard deduction this year, I would consider not donating until at least January 1 at this point. Maybe something will change for them in 2026 (e.g., a better-paying job triggering more state/local taxes and allowing more donations) that could make the donations useful for tax purposes in that year.

Veganuary seeming against it is part of the bit.

So this is . . . . ~EA kayfabe? (That term refers to "the portrayal of staged elements within professional wrestling . . . . as legitimate or real.").

In particular, I genuinely feel like EA would have more traction if it distanced itself from the concept of pledging 10% because most people I feel like donate between $30-50$ per month not like thousands of dollars in a year.

For the population that is interested in giving a few hundred dollars a year, I suspect that individual-charity efforts without the EA branding or intellectual/other overhead are going to be more effective. So I don't think there is an either/or here; one can run both sorts of asks without too much interference between the two.

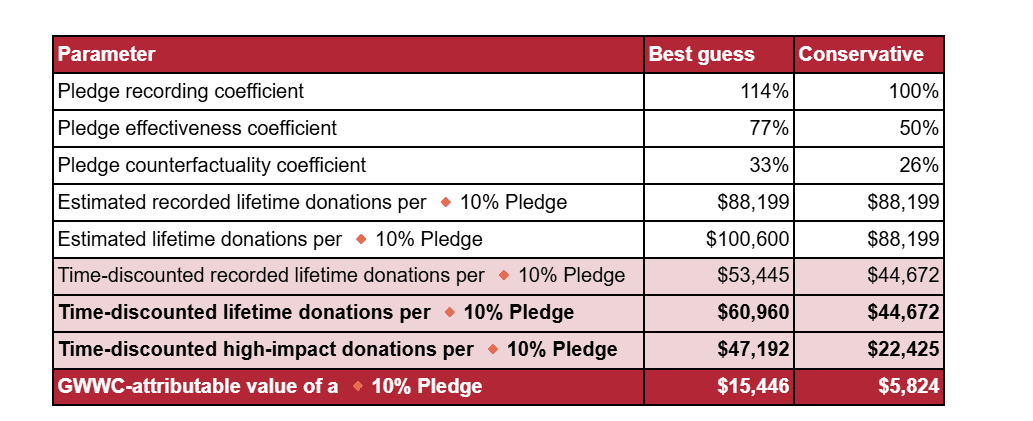

Although that's an estimate of how much counterfactual value "GWWC generates" from each pledge, which is less than the full value of the pledge. Elsewhere, it is called GWWC-attributable value. The full value is more like $47-60K on best guess.

Therefore I don't fundamentally think that donor orgs need to pay more to attract similar level of talent as NGOs.

Additional reasons this might be true, at least in the EA space:

- GiveWell, CG, etc. may be (or may be perceived as) more stable employers than many potential grantees. I'm pretty confident that they will be around in ten years, that the risk of budget-motivated layoffs is modest, and so on. This may be a particular advantage for mid-career folks with kids and mortgages who are less risk tolerant than their younger peers.

- It may be easier -- or at least perceived as easier -- to jump from a more prestigious role at a funder to another job in the social sector than it would be from a non-funder role. So someone in the private sector could think it less risky to leave a high-paying private sector job to work at GiveWell than to work at one of its grantees, even if the salaries were the same.

While you avoid capital gains tax when donating appreciated stock to a 501(c)(4), you will want to confirm with the organization that it will be able to avoid taxation on the capital gain as well. The 501(c)(4) takes the donor's basis in the donated stock under the general rule for gifts at I.R.C. 1015(a).

A 501(c)(4) is subject to tax under I.R.C. 527(f) on the lesser of its net investment income or

certain political activity. My understanding is that tax usually hits at 35%, and so paying it is worse than the donor paying at 15-23.8% and then donating the balance. On the other hand, I believe that organizations can get around this if they can avoid having net investment income and certain political expenditures in the same year. The org should know if it is going to have the specified type of expenditures in a year it may sell the donated, appreciated stock.