Jonas_

Posts 24

Comments622

Topic contributions3

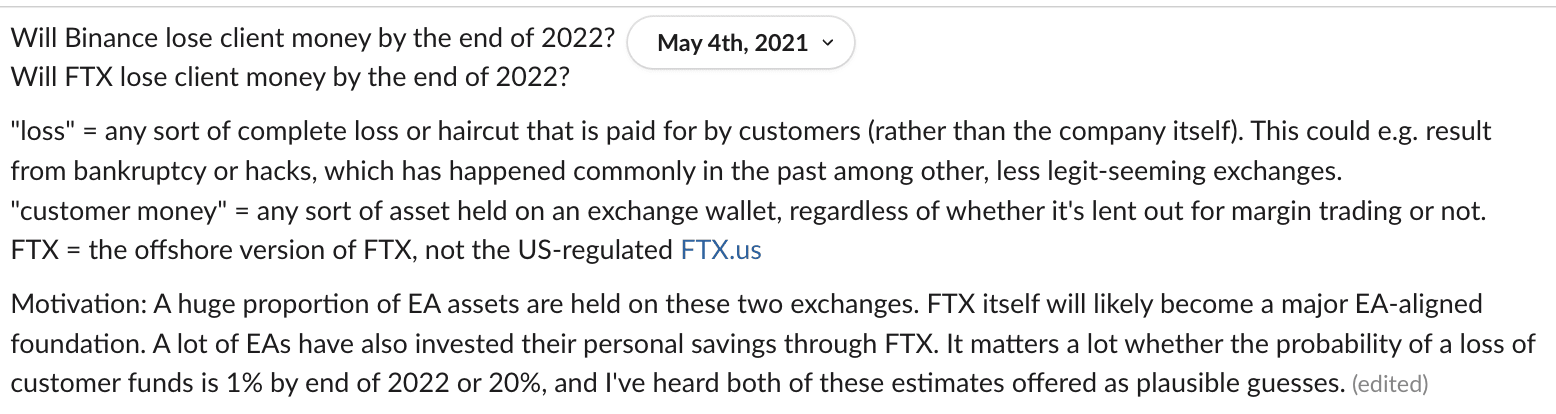

I recall feeling most worried about hacks resulting in loss of customer funds, including funds not lent out for margin trading. I was also worried about risky investments or trades resulting in depleting cash reservers that could be used to make up for hacking losses.

I don't think I ever generated the thought "customer monies need to be segregated, and they might not be", primarily because at the time I wasn't familiar with financial regulations.

E.g. in 2023 I ran across an article written in ~2018 that commented an SIPC payout in a case of a broker co-mingling customer funds with an associated trading firm. If I had read that article in 2021, I would have probably suspected FTX of doing this.

A 10-15% annual risk of startup failure is not alarming, but a comparable risk of it losing customer funds is. Your comment prompted me to actually check my prediction logs, and I made the following edit to my original comment:

- predicting a 10% annual risk of FTX collapsing with

FTX investors and the Future Fund (though not customers)FTX investors, the Future Fund, and possibly customers losing all of their money,

- [edit: I checked my prediction logs and I actually did predict a 10% annual risk of loss of customer funds in November 2021, though I lowered that to 5% in March 2022. Note that I predicted hacks and investment losses, but not fraud.]

I don't think so, because:

- A 10–15% annual risk was predicted by a bunch of people up until late 2021, but I'm not aware of anyone believing that in late 2022, and Will points out that Metaculus was predicting ~1.3% at the time. I personally updated downwards on the risk because 1) crypto markets crashed, but FTX didn't, which seems like a positive sign, 2) Sequoia invested, 3) they got a GAAP audit.

- I don't think there was a great implementation of the trade. Shorting FTT on Binance was probably a decent way to do it, but holding funds on Binance for that purpose is risky and costly in itself.

That said, I'm aware that some people (not including myself) closely monitored the balance sheet issue and subsequent FTT liquidations, and withdrew their full balances a couple days before the collapse.

Nitpick:

Gary Marcus was shared the full draft including all the background research / forecast drafts. So it would be more accurate to say "only read bits of it".