Neil Warren

Posts 5

Comments15

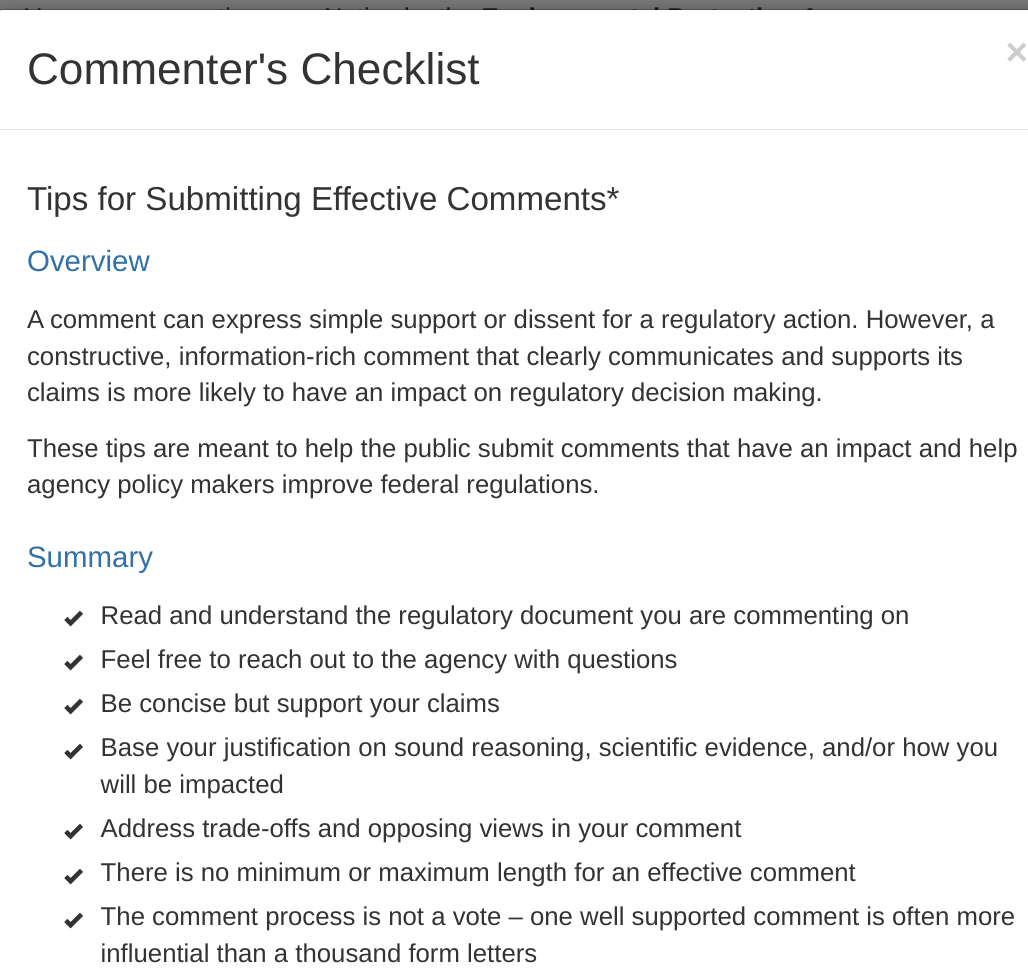

Another thing you can do is send comments proposed legislation on regulations.gov. I did so last week about a recent californian bill on open-sourcing model weights (now closed). In the checklist (screenshot below) they say: "the comment process is not a vote – one well supported comment is often more influential than a thousand form letters". There are people much more qualified on AI risk than I over here, so in case you didn't know, you might want to keep an eye on new regulation coming up. It doesn't take much time and seems to have a fairly big impact.

I wrote a post on moth traps. It makes a rather different point, but I still figure I'd better post it here than not. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/JteNtoLBFZB9niiiu/the-smallest-possible-button-or-moth-traps

I think this is my favorite so far. There's a certain hope and cozyness radiating from it. Great introduction to the hopeful let's-save-the-world! side of EA that I will send to all my non-EA friends.

Your videos are extremely practical for that purpose. In my experience there's a certain "legitness" that comes with a nicely animated video on YouTube with more than 100k views, that a blog post doesn't have. So thanks! :)

Okay forget what I said, I sure can tie myself up in knots. Here's another attempt:

If a person is faced with the decision to either save 100 out of 300 people for sure, or have a 60% chance of saving everyone, they are likely (in my experience asking friends) to answer something like "I don't gamble with human lives" or "I don't see the point of thought experiments like this". Eliezer Yudkowsky claims in his "something to protect" post that if those same people were faced with this problem and a loved one was among the 300, they would have more incentive to 'shut up and multiply'. People are more likely to choose what has more expected value if they are more entangled with the end result (and less likely to eg signal indignation at having to gamble with lives).

I see this in practice, and I'm sure you can relate: I've often been told by family members that putting numbers on altruism takes the whole spirit out of it, or that "malaria isn't the only important thing, coral is important too! " , or that "money is complicated and you can't equate wasted money with wasted opportunities for altruism".

These ideas look perfectly reasonable to them but I don't think they would hold up for a second if their child had cancer: "putting numbers on cancer treatment for your child takes the whole spirit out of saving them (like you could put a number on love)", or "your child surviving isn't the only important thing, coral is important too" or "money is complicated, and you can't equate wasting money with spending less on your child's treatment".

Those might be a bit personal. My point is that entangling the outcome with something you care about makes you more likely to try making the right choice. Perhaps I shouldn't have used the word "rationality" at all. "Rationality" might be a valuable component in making the right choice, but for my purposes I only care about making the right choice no matter how you get there.

The practical insight is that you should start by thinking about what you actually care about, and then backchain from there. If I start off deciding that I want to maximize my family's odds of survival, I think I am more likely to take AI risk seriously (in no small part, I think, because signalling sanity by scoffing at 'sci-fi scenarios' is no longer something that matters).

I am designing a survey I will send tonight to some university students to test this claim.

Hello! Thanks for commenting!

- How does that work? In your specific case, what are you invested in but also are detached from the outcome? I can imagine enjoying life as working like this: eg I don't care what I'm learning about if I'm reading a book for pleasure. Parts of me also enjoy the work I tell myself helps with AI safety. But there are certainly some parts of it that I dislike, but that I do anyway, because I attach a lot of importance to the outcome.

- Those are interesting points!

- 1) Mud-dredging makes rationality a necessity. If you've taken DMT and have had a cosmic revelation where you discovered that everything is connected and death is an illusion, then you don't need to actively not die. I know people to whom death or life is all the same: my point is that if you care about the life/death outcome, you must be on the offensive, somewhat. If you sit in the same place for long enough, you die. There are posts about "rationality = winning", and I'm not going to get into semantics but what I meant here by rationality was "that which gets what you want". You can't afford to eg ignore truth when something you value is at risk. Part of it was referencing this post, which made clear for me that entangling my rationality with reality more thoroughly would force me into improving it.

- 2) I'm not sure what you mean. We may be talking about two different things: what I meant by "rationality" was specifically what gets you good performance. I didn't mean some daily applied system which has both pros and cons to mental health or performance. I'm thinking about something wider than that.

As for that last point, I seem to have regrettably framed creativity and rationality as mutually incompatible. I wrote in the drawbacks of muddredging that aiming at something can impede creativity, which I think is true. The solution for me is splitting time up into "should" injunctions time and free time fooling around. Not a novel solution or anything. Again it's a spectrum, so I'm not advocating for full-on muddgredging: that would be bad for performance (and mental health) in the long run. This post is the best I've read that explores this failure mode. I certainly don't want to appear like I'm disparaging creativity.

(However, I do think that rationality is more important than creativity. I care more about making sure my family members don't die than about me having fun, and so when I reflect on it all I decide that I'll be treating creativity as a means, not an end, for the time being. It's easy to say I'll be using creativity as a means, but in practice, I love doing creative things and so it becomes an end.)

Is there any situation you predict in which Google donation matches would affect METR's vision? What is the probability of that happening, and what is the value of donations to METR by Google employees?

If you're asking for advice, it seems to me that refusing donations on principle is not a good idea, and that donation matching from Google for employee donations carry no legal bearing (but I have no idea) and are worth the money. Besides, I understand the importance of METR independence, but are Google and METR's goals very orthogonal? Your final calculation would need to involve degree of orthogonality as well. I'm not a very valuable data point for this question, however.

The book in my opinion is better, and relies so much on vast realizations and plot twists that it's better to read it blind—before the series and before even the blurb at the back of the book! So for those who didn't know it was a book, here it is: https://www.amazon.fr/Three-Body-Problem-Cixin-Liu/dp/0765377063