Tristan Katz

Bio

Participation4

I recently completed a PhD exploring the implications of wild animal suffering for environmental management. You can read my research here: https://scholar.google.ch/citations?user=9gSjtY4AAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

I am now considering options in AI ethics, governance, or the intersection of AI and animal welfare.

Posts 5

Comments72

It seems to me that the 'alien preferences' argument is a red herring. Humans have all kinds of different preferences - only some of ours overlap, and I have no doubt that if one human became superintelligent that would also have a high risk of disaster, precisely because they would have preferences that I don't share (probably selfish ones). So they don't need to be alien in any strong sense to be dangerous.

I know it's Y&S's argument. But it would have been nice if the authors of this article had also tried to make it stronger before refuting it.

Like others I find the question to present a false dichotomy.

Similarly, I find it much easier to take someone's commitment to animal advocacy seriously if they're vegan, and I think it's the best way to be internally consistent with your morals. I also think that anyone who is buying meat is contributing to harm, even if they offset. In that sense it's a 'baseline', but I still think offsetting is good, and I don't want to exclude anyone from being animal advocates, because I know veganism is hard and people are motivated by different things.

I think of it like anti-smoking campaigns: smoking is not good. If you donate and smoke, well that's good overall but still I'd rather you didn't smoke. And your smoking shouldn't stop you from being able to fight the tobacco lobby!

So: yes, a baseline, but not a requirement. Offsetting is good, but not a legitimate stopping point.

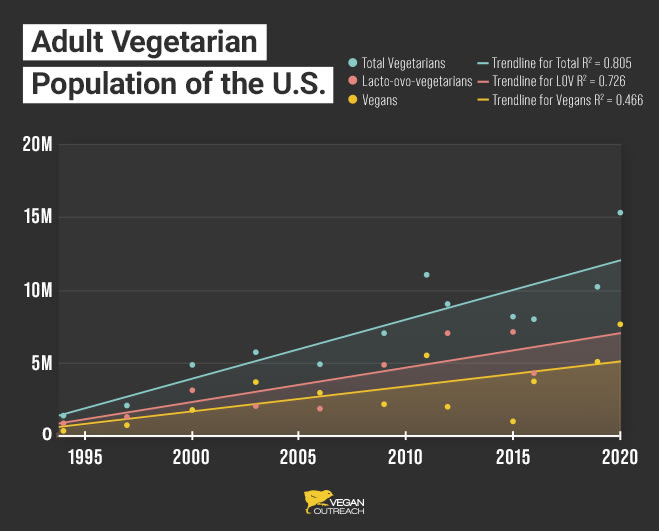

stagnant levels of veganism over the past few decades (between 1%-5%

I don't think this is true. It would be true if you talked about the last one decade - survey results seem to show a pretty clear fluctuation, rather than rise. But I'm afraid that EAs are over-updating because of this. Although survey data is more patchy before that, they show a pretty remarkable rise in veganism over my lifetime (i.e. 30 years) and I definitely see that in my own life.

I agree with all of this. But does this mean your answer is: yes, in most cases we should treat veganism as a moral baseline? Since the norms you say we should push for (plan-based, avoiding animal testing) do seem to entail veganism. I can imagine this varying by context - pushing for these norms might mean treating veganism as a baseline for advocates in Germany, but maybe not in Spain or China*, given that it's just way harder to follow those norms strictly there.

*Countries chosen based on my ignorant perception of them

Hey Mal, this is a great point, I completely agree. The disease doesn't have to be worse than all possible ways of dying if you know that the counterfactual is likely to be a particular mid-intensity harm. Although the welfare gains should still be significant in order to justify the ecological risks.

Oh I see I'd misunderstood your point. I thought you were concerned about lowering the number of warble flies. This policy wouldn't lower the number of deer - it would maintain the population at the same level. This is for the sake of avoiding unwanted ecological effects. If you think it's better to have more deer, fair enough - but then you've got to weigh that against the very uncertain ecological consequences of having more deer (probably something like what happened in Yellowstone Nationa Park: fewer young trees, more open fields, fewer animals that depend on those trees, more erosion etc)

No - and I wasn't meaning to say that less beings with higher welfare is always better. Like I said, I don't think the common sense view will be philosophically satisfying.

But a second common sense view is: if there are some beings whose existence depends on harming others, then them not coming into existence is preferable.

I expect you can find some counter-example to that, but I think most people will believe this in most situations (and certainly those involving parasites).

I think the evolution analogy becomes relevant again here: consider that the genus Homo was at first more intelligent than other species but not more powerful than their numbers combined... until suddenly one jump in intelligence let homo sapiens wreak havoc across the globe. Similarly, there might be a tipping point in AI intelligence where fighting back becomes very suddenly infeasible. I think this is a much better analogy than Elon Musk, because like an evolving species a superintelligent AI can multiply and self-improve.

I think a good point that Y&S make is that we shouldn't expect to know where the point of no return is, and should be prudent enough to stop well before it. I suppose you must have some source/reason for the 0.001% confidence claim, but it seems pretty wild to me to be so confident in a field like that is evolving and - at least from my perspective - pretty hard to understand.