by Danilo Vicioso and Clinton Ignatov

Abstract

In this informal and unconventional introduction to a new relation of life to science, we address the question “what is the meaning of life?” by first establishing that life may have meaning itself. This is by no means a straightforward matter, and so this essay must be by no means straightforward. It is, we hope, comprehensive and provocative.

We start off by defining life as an objective attribute inherent to all systems. We elucidate the paradox that life is both diverse—individuals have different definitions of the meaning of life—while recognizing that life itself has inherent universal meaning. We then provide artifactual examples to ground our meaning in the form of buildings, people and technology. We discuss the universality of life as a potential society wide alignment mechanism and explore recent advancements in science that enable life to be verifiable. We conclude with further research that needs to be done to advance the measurement of life, and provide a few leads and loose strings to tug upon.

Reactions are welcome and refutations would be celebrated. Sources include Christopher Alexander, Erwin Schrodinger, Ramray Bhat, Max Olson, John H. Clippinger, Ph.D and Peter Hirshberg

Living Machines

In a time when computers are said to be challenging human intellectual dominance on our planet, there is a need to return to some basic questions. First and foremost, if we are to talk to computers as though they were alive—and we are doing so already—then a clear starting point is in establishing a comprehensive understanding of just what life is.

For nearly 300 years, since Linnaeus first created taxonomies of species, the study of life has formally been the purview of the biological sciences. Beginning in the 1950s, however, early computer scientists and cyberneticists, such as Alan Turing and Norbert Wiener, began proposing serious questions about the possibility of understanding machines as a form of life. Turing proposed that a human interlocutor which couldn’t differentiate a mediated dialogue with a machine from that with a person would have to consider the machine to be alive. Weiner demonstrated means by which computer abstractions could be self-reproducing. Later, John Conway’s Game of Life, coming out of automata theory, possessed the minds of an entire generation of computer scientists in the 1970s with its endlessly generating patterns of life-forms.

The voice interface of science fiction television has been, for the last decade, a reality in many of our day-to-day lives. Adults and children spend hours immersed in virtual environments full of life-like characters with whom they engage in rich relations in games and simulations. Our digital communications media are becoming more and more immersive, now culminating in designs such as the metaverse and in overlays which augment our embodied reality. And popular fiction portends to a day when fully embodied machines are indifferentiable from humans.

Many fields of intellectual theory have delved into these histories, and tried to broaden our understanding of life given them. Most notably, post-humanism discusses the ways in which human bodies and minds are “spliced” into cybernetic models, systems of machines and semiotic flows.

But all these framings, nevertheless, merely extend the biological idea of life one-further conceptually. This stretching is severely limited.

On the one hand, it is a stretch too far to compare hand-fashioned circuits and machines—no matter how small, or how quickly their circuits flicker their charges—with all the complexity of biological cells, proteins, evolutionary processes, and the other complex systems comprising natural biology. And analogically and surgically splicing artificial systems into biological and psychological ones provides no coherent answers about what life might be as a common, unifying principle across both domains.

On the other hand, there isn’t enough of a stretch taken in equating or splicing together biological and artificial systems, because it can only go so far as presenting life as those things that plants, animals, and humans do which computers and other artificial things can ape or mimic or interface with.

Beyond the world of biology, is there another way of asking the question “what is life?” which escapes the problems of incredulity about machine consciousness, on the one hand, and casts a wider net than merely encompassing a few human-made mechanisms, on the other? Which even transcends biology as an answer without leaving the scientific epistemology?

We believe that there is.

Thesis

Universal principle of life: life is an objective, measurable attribute inherent to some degree in all systems including non-biologically alive systems. Humans universally recognize degrees of life: one meadow is more alive than another, one company more alive, homes more dead than the next, one conversation more than another–this is automatic and pre-wired. Regardless of their nature, every entity, whether it be a dwelling, a conversation, or a physical object like concrete, possesses a scientifically measurable degree of life. Our only present measurement apparatus is our own selves, but this is not to say that our definition of life is subjective or anthropocentric. It can be formalized and abstracted. This sense of varying degrees of life in different things is widely held and can be quantified in any connected region of space, regardless of its size.

The difference in degree of life that we discern in things is not a subjective assessment, but an objective one. It describes something about the world, which exists in the world, and resides in structure. What we call “life” is a general condition which exists, to some degree or other, in every part of space: brick, stone, grass, river, painting, building, daffodil, human being, forest, city. And further: The key to this idea is that every part of space—every connected region of space, small or large—has some degree of life, and that this degree of life is well defined, objectively existing, and measurable. The quality of life is not precious or “high” in this sense at all. It exists also, quite easily, in the most humble and ordinary aspects of our daily lives. In this sense the great life we feel in works by Matisse and van Gogh is somewhat misleading—since the same feeling of life can occur, also, in a dirty hut or in a slum—and, indeed, is often more likely to occur in such a place than in a work of “architecture.” This is confusing, because it seems contradictory. Yet it is fundamental. We do feel that there are different degrees of life in things—and that this feeling is rather strongly shared by almost everyone. In every moment, policy, action, line, shape, do the thing or take that action to increase life. We shall see later that this feeling that there is more life in one case than the other is correlated with a structural difference in the things themselves—a difference which can be made precise, and measured.—Christopher Alexander

Architecture

As an architect and mathematician, Berkeley University’s Christopher Alexander grappled with the question of life for decades. Buildings being his domain, his thoughts about life were timeless, centered in the physical spaces within which people have always lived, worked, and played.

Gardens and terraces, temples, houses, towers, marketplaces; for our ends, these human-scale worlds of real buildings and habitats present the ideal starting place for appreciating ideas about life beyond the biological meaning.

There are no splices or gaps convoluting Christopher Alexander’s pure vision of our relation to the life of forms, artificial and natural. Those modern, post-modern, and post-human complications—products of modern technology and the strange environments or arenas they create—can be more easily addressed and confronted after we come to understand what Alexander had to say about life in a more timeless sense.

Life in Examples

Let’s begin with Alexander’s rigorous empirical explorations into the life of architecture.

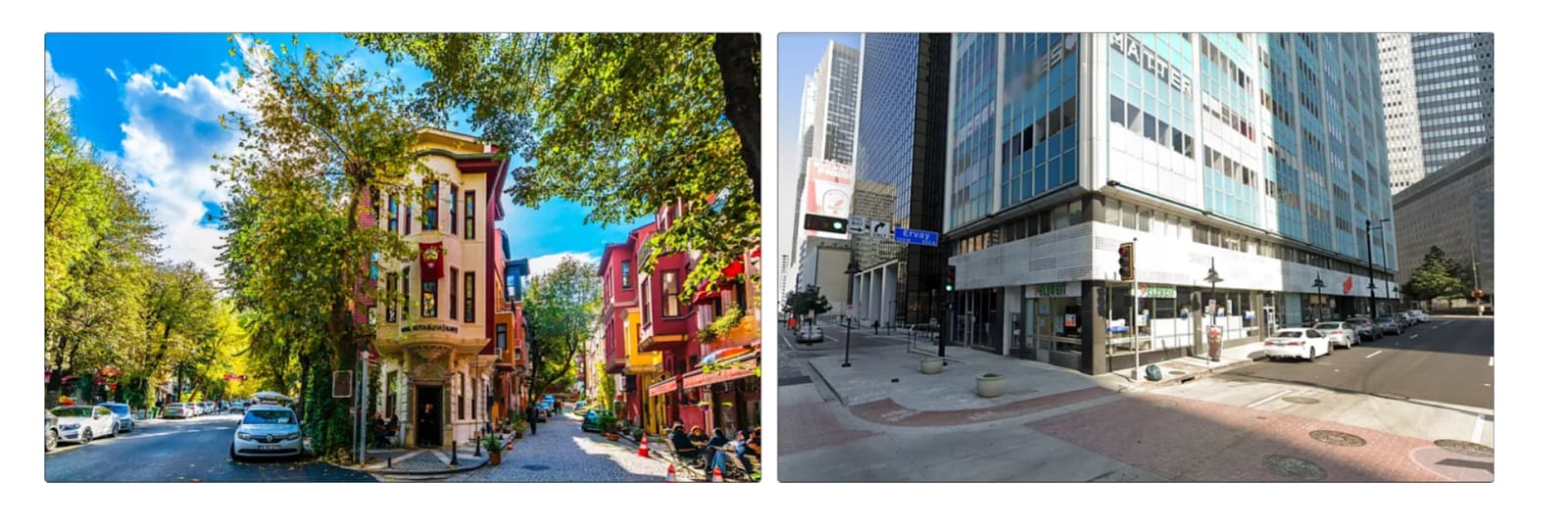

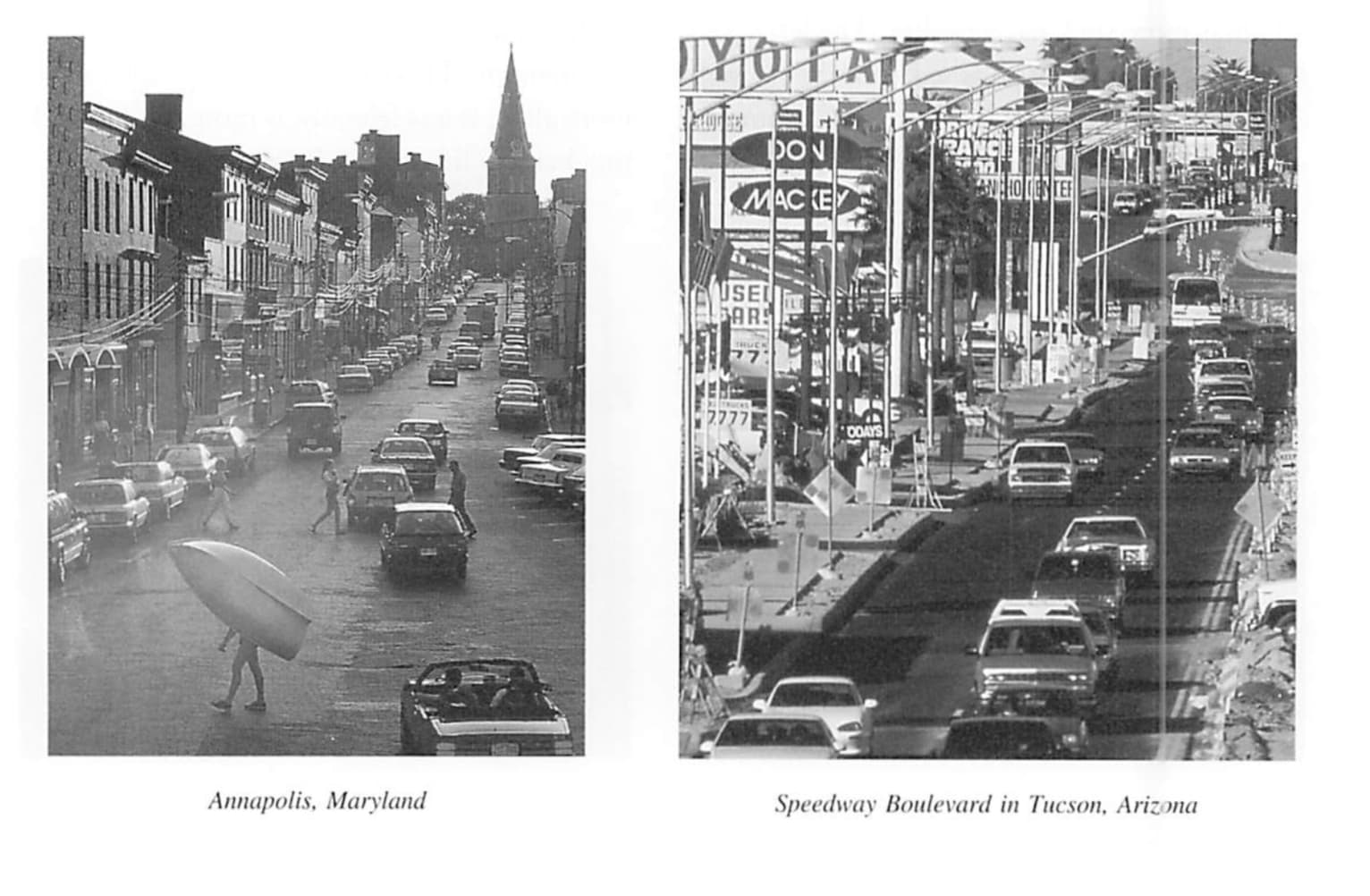

The following pictorial comparison is from Max Olson’s The Grand Unifying Theory of Design. He asks “Which street makes you feel more “alive”? What are the patterns in each that contribute to positive or negative emotion? What about good or poor fit with needs?”

The quality of life is not precious or “high” in this sense at all. It exists also, quite easily, in the most humble and ordinary aspects of our daily lives. In this sense the great life we feel in works by van gogh is somewhat misleading—since the same feeling of life can occur, also, in a dirty hut or in a slum.—Christopher Alexander

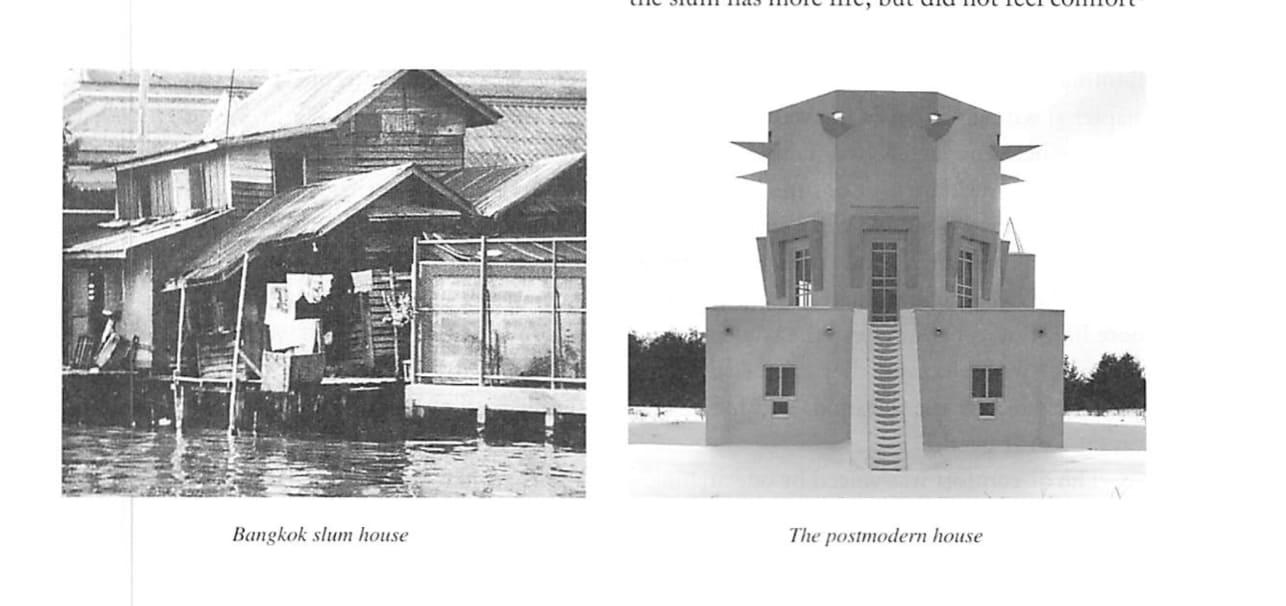

Olsen was following Christopher Alexander’s example in this style of presentation. In 1992 Alexander asked 110 architecture students at the University of California which of the following two images had more life:

Of the 110, 89 said that the Bangkok slum house does, and 21 chose to say the question didn’t make sense or they couldn’t make a choice. Precisely zero said that the octagonal tower has more life. Explains Alexander,

For some people the answer was obvious. for others, it was at first not a comfortable question. Some asked “what do you mean? What is the question supposed to mean? what is your definition of life?” and so on. I made it clear that I was not asking people to make a factual judgment, but just to decide which of the two, according to their own feeling, appear to have more life. Even so, the question was not quite comfortable for everyone.

These students were embarrassed by a conflict between the values they were being taught, and a truth they perceived and could not deny. In spite of themselves, they saw some of the quality of ordinary life, with all the feelings that entails, present in the slum, regardless of its poverty, hunger, and disease.

Poverty appears frequently in Alexander’s many comparisons, often favorably on the life-exhibiting scale. This is a tricky observation to make, and must be handled with compassion and regard for human dignity and need. Nevertheless, it is essential to understanding the nature of life. Life entails risk, sacrifice, death and birth. The nature of scarcity of resources, and the roles of resources and needs in living systems is never so apparent than when seen within conditions where life perseveres in spite of many challenges and deprivations. Through necessity and intuition, the simpler examples of lower-class and impoverished living exhibit, paradoxically, more elements of life. In such situations, life can still often persevere, grow, and even thrive.

“… Life occurs most deeply when things are simply going well, when we are having a good time, or when we are experiencing joy or sorrow – when we experience the real.”

“ The degree of life is always there, whether the thing is good or bad.”

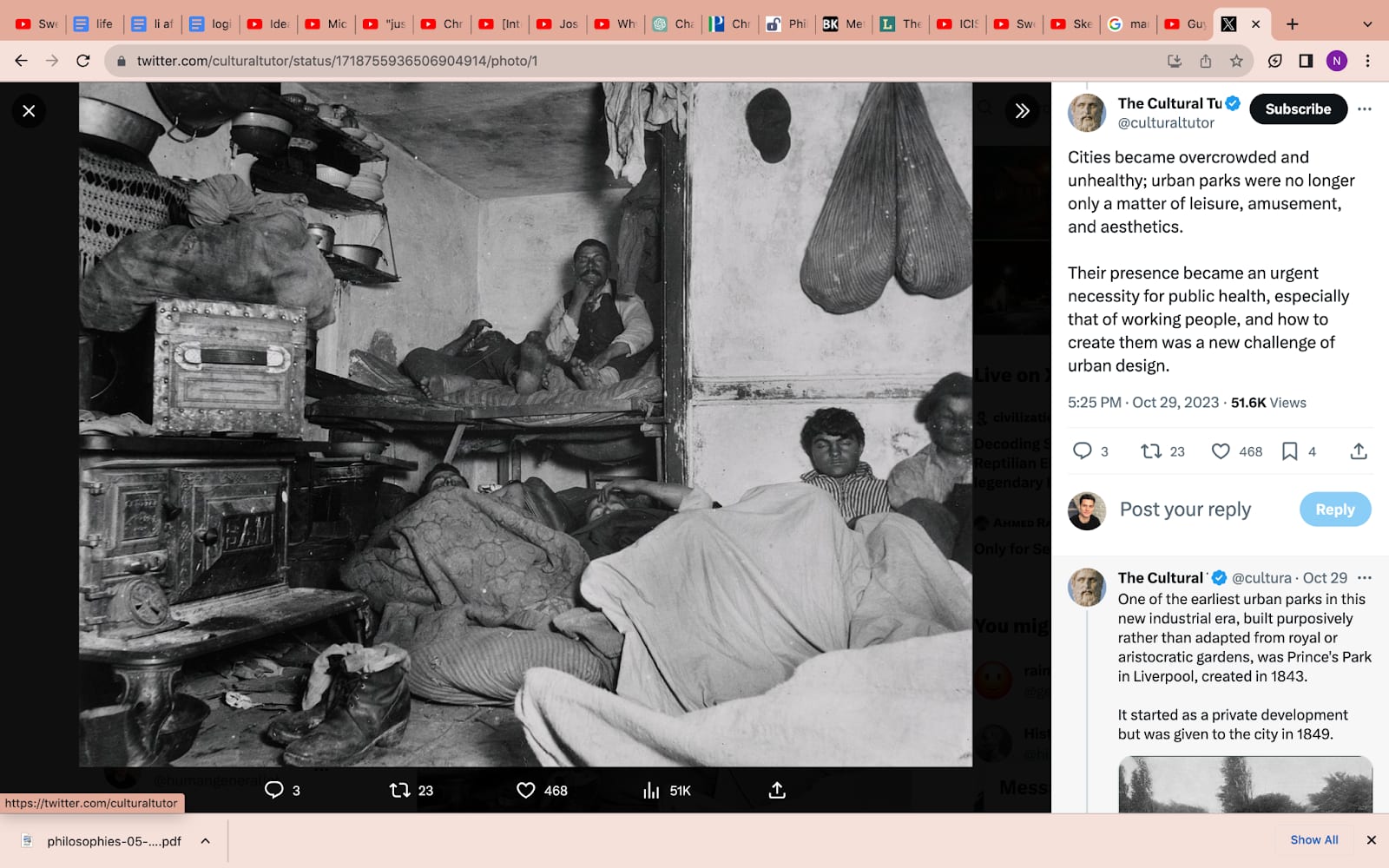

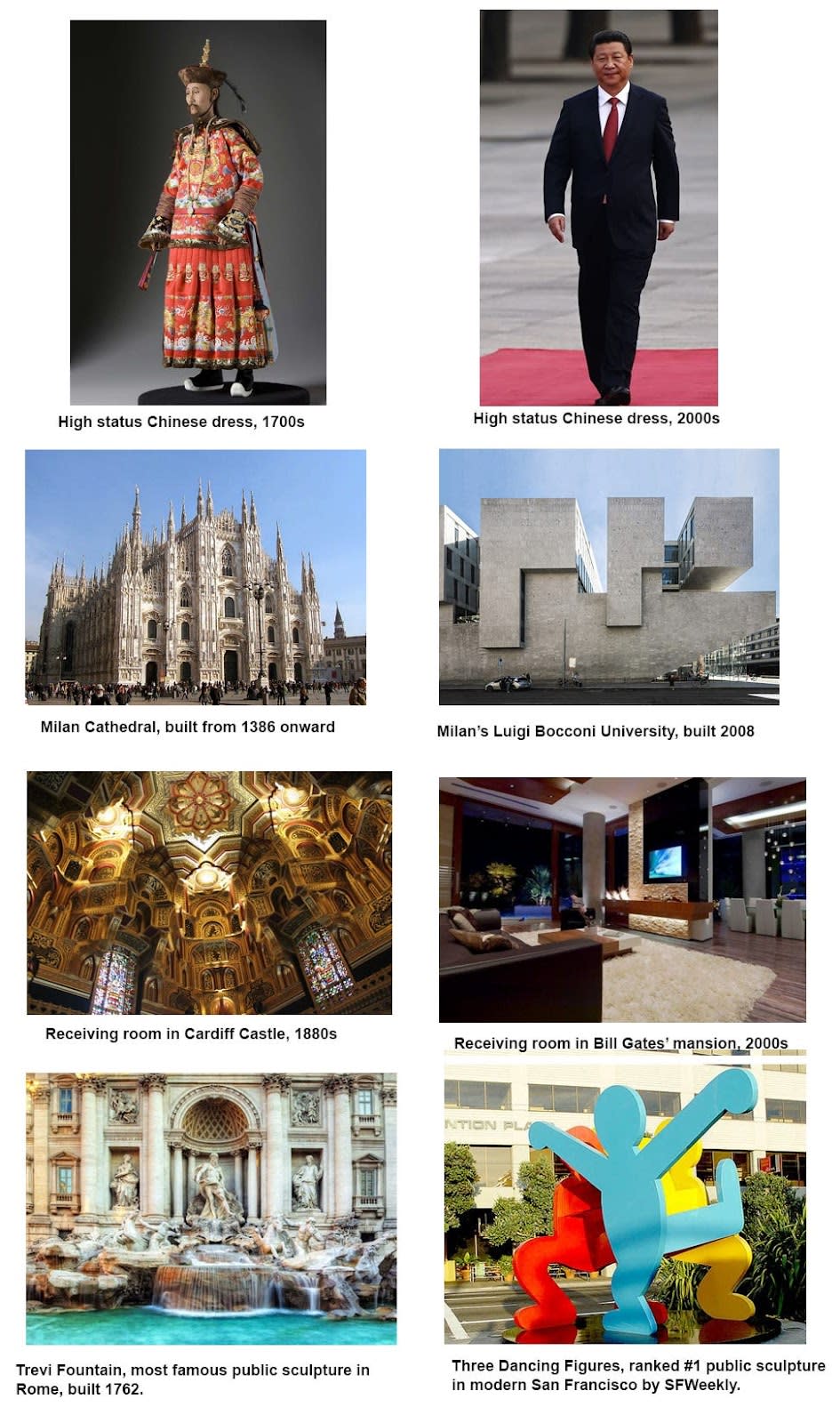

The two images below are from Scott Alexander’s essay Whither Tartaria, in which Scott was attempting to understand why art and architecture is no longer beautiful.

The images on the left are harmonious; at a gut level one can literally feel the difference in human care and the subsequent life that went into it. The statue in the right image may be cute. The characters are even animated in movement while being still as stone. But could you insist it has more life?

Beauty is traditionally considered to be in the eye of the beholder, meaning that it is subjective, varying from person to person or from time to time. Alexander, however, challenged this traditional wisdom, arguing that what we call beauty exists physically as a living structure, not only in arts but also in our surroundings, and it can be quantified and measured mathematically. He further claimed that the quality of architecture is objectively good or bad for human beings, rather than only a matter of opinion. There is a shared notion of beauty among people regardless of their faiths, ethics, and cultures, and it accounts for 90% of our feelings. The idiosyncratic aspect of beauty accounts only 10% of our feelings, and depends on relatively small differences of individual life and cultural history or biology. As Alexander claimed, beauty or order coming from a segment of music is no different from that of a physical thing like a tree, since both the music and the tree possess the kind of living structure with far more smalls than larges. Both life and beauty come from the same source, the very concept of wholeness. Thus, wholeness, life, and beauty constitute a trinity, which is the foundation of the nature of order. —Christopher Alexander and His Life’s Work: The Nature of Order by Bin Jiang

The properties of life and beauty in our cities are a perennial concern, shared by many discerning people who are in touch with the feelings which their environments provide them. We are saying nothing new in observing the ugliness of modern urban landscapes, we are only offering ways to integrate those perceptions into a model amenable to scientific and philosophical exploration.

More examples for exploring your perception of life abound on the internet. The lack of human care and lifelessness of the right-hand exhibits below, shared by #GoodUrbanist @wrathofanon on X are self-evident.

And the subreddit /r/UrbanHell overflows with images such as the following, with its bleak forms, and wash-out of red tail-lights in roads which are taking nobody anywhere.

Christopher Alexander addresses these wider urban landscapes as well.

Two congested streets, both in downtown areas of cities, Tucson and Annapolis. Still, one of them (Annapolis) has detectably more life than the other. The large poles in Tucson are intrusive and thus create a sense of suppression that blocks the fluidity that is life.

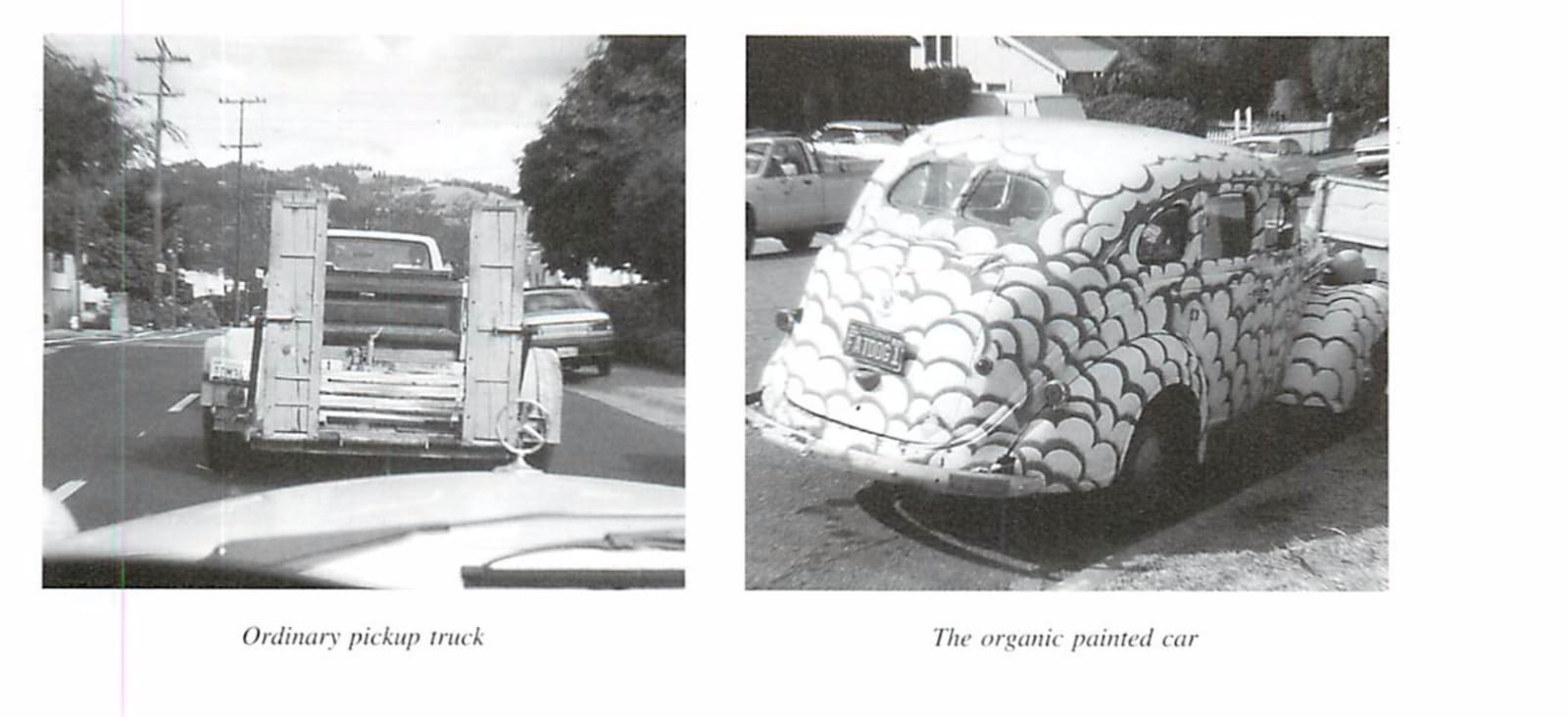

The funky and organic image is not always the one with more life. Here the painted car from California seems to symbolize life, and might therefore be chosen as more alive by an unwary reader. but if you ask yourself which of the two actually has more life, makes you feel more in touch with life in yourself, has more of the truth of everyday events in it. you may then find that the pickup truck, ordinary though it is, is more genuinely in touch with life, more connected. The organic car is more an image than it is genuinely connected to life. The pickup truck looks less inspired, but it is more truly alive.—Christopher Alexander

It may seem, from the examples provided, that perceivers of life will automatically favor antiquity over modernity… this is not the case. The issue is that modern architecture, and design at large, is greatly complicated by the ways systems and machines are spliced into our sense of reality. Before industrialization and its fruits, design was entirely human scale and hand-crafted, and the life within things more readily apparent. But modern technology has the ability to produce life as much as it has been, all too often, diminishing. It is a matter of creating living forms.

So let’s consider some contemporary videos to understand how artists and designers are today handling, or failing to handle, these considerations.

Lil Yachty with the HARDEST walk out EVER

This scene is full of life. What we can see here is not simply the physical attributes. The music is loud, the crowd is making a lot of noises. Lil yachty and the crowd are jumping up and down. What we can see here is that the crowd is alive. We see the same living energy in this Tomorrowland concert.

Sunnery James & Ryan Marciano | Tomorrowland 2023

Science, so long as it fails to understand life in this all-encompassing way, has a tendency to reduce or fracture things to instrumentally-measurable qualities, neglecting their deeper, hidden, or "withdrawn" essence. But life has an irreducible autonomy or independence.

One person may be glowing with life, which transmits to everyone around. another person is drooping ... different organisms, all alive in the strictly mechanical sense, impress us as having more life or less life. The difference in the amount of life between the two should be apparent.—Christopher Alexander

The creative marketing minds behind the world's most successful products understand these principles well. Consider this Apple commercial for example.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRPqGf8nc4g

We concede that smartphones, at a fundamental level, are far more than mere commodity electronics. But in this commercial, we see that the smartphone applied as a commodity electronic device offers a lot to enhance living at the human scale. Google also knows how to demonstrate their software products as enablers of life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcHV_Dv9tlo

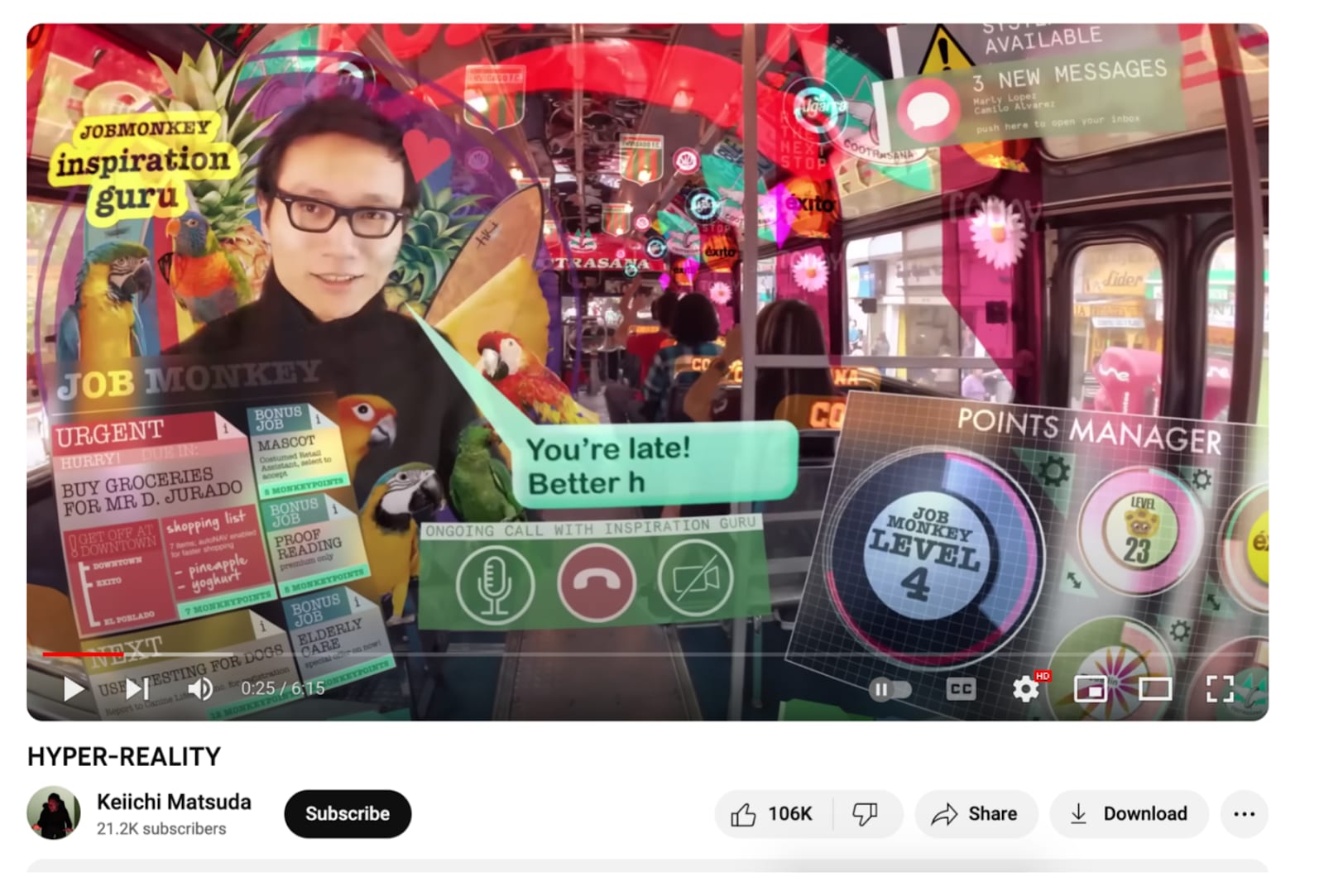

To the contrary, the mockumentary HYPER-REALITY by Keiichi Matsuda shows us a fake, sick, weak, fearful, strained, inhibited, noisy technological environment. An environment which is, ultimately, destroyer of life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJg02ivYzSs

This is also the dystopian world of Terry Gilliam’s motion picture sci-fi Zero Theorem, starring Christoph Waltz.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HWgPnQi-XG4

These last two visions are of worlds which are certainly animated—and so might be naively claimed to be “living” or “full of life.” But they are without proportion, without strong centers, without the living structures of Alexander’s fifteen properties of life, which we will explore more deeply later in this essay. For now though, we can already see that they lack simplicity and inner calm. They starkly separate one’s consciousness from one’s embodied life—what is animated is unnaturally spliced in. They destroy any sense of positive space or fullness, and invade our boundaries.

As you may be beginning to see, life is a universal term that appreciates and affords the diversity of being which is essential today. Life is non-partisan and apolitical. Life transcends ideology, ethnicity and class agnostic. And, if studied, life and life-sustaining forms can be created out of processes analogous to how biological life and the natural world have formed and sustained us throughout our evolution.

Others on Alexander

In 1944, the celebrated physicist, Erwin Schrodinger, famously asked, “What is Life?” Neither Schrodinger nor generations of illustrious scientists after him have been able to satisfactorily answer this question.—Ramray Bhat on Understanding Complexity, Life Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

We put forward the claim that life, following in Christopher Alexander’s sense of the meaning, should be the core of all scientific research. This is a teleological injunction which has already been taken to heart by many of the most creative minds in our culture today.

Alexander’s influence also extended far beyond architecture and urbanism. Ward Cunningham, inventor of wiki (the technology behind Wikipedia), credits Alexander with directly inspiring that innovation, as well as pattern languages of programming, and the even more widespread Agile methodology. Will Wright, creator of the popular games Sim City and The Sims, also credits Alexander as a major influence, as do the musicians Brian Eno and Peter Gabriel. Apple’s Steve Jobs was also said to be a fan.—Michael W. Mehaffy, Why Christopher Alexander Still Matters

“Christopher Alexander's work in The Nature of Order showed, quite convincingly, that our judgment of life is also innate. He also argued extensively that this innate faculty is deeply entangled with the natural laws of physics, chemistry, biophysics, et cetera”—Greg Bryant, Reflections on PUARL

But let us now delve deeper into Alexander’s own descriptions from his four-part book The Nature of Order so as to get at his sense of what “life” is really all about.

... the “life” which I am talking about also includes the living essence of ordinary events in our everyday worlds... a back-street Japanese restaurant... an Italian town square... an amusement park... a bunch of cushions thrown into a corner window-seat... this quality includes an overall sense of functional liberation and free inner spirit. above all it makes us feel alive when we experience it.

It is undeniable–at least as far as our feeling is concerned, that a... breaking wave feels as if it has more life as a system of water than an industrial pool stinking with chemicals. so does the ripple of a tranquil pond. a fire, which is not organically alive, feels alive. and a blazing bonfire may feel more alive than a smoldering ember.

...we recognize degrees of life, or degrees of health, in different ecological systems... one meadow is more alive than another, one stream more alive... one forest more tranquil, more vigorous, more alive, than another dying forest ...

...life occurs most deeply when things are simply going well, when we are having a good time, or when we are experiencing joy or sorrow–when we experience the real.

To see it, one needs to dig beneath much of our mental life, including years of indoctrination that all people, professional or not, are subject to. Our instincts are stimulated and trained to respond to anything that's flashy, or trendy, or familiar, or tricky. But it's not hard to put aside this training, and isolate a particular shared faculty of judgment: the one which allows us to judge the existence of living structure. People agree when asked which things “have more life,” or ”reflect inner calm,” or seem “more like nature,” or “make you feeling more profoundly human.”

Sarah Perry in Centers writes about Alexander

“In The Timeless Way of Building (1979), Christopher Alexander argues for the counterintuitive proposition that feeling (in the sense of perceiving the beauty and “life” of a space), unlike ideas or opinions, is quite objective; there is an astounding level of agreement between people about how different environments and buildings feel, though there may be little agreement of opinions or ideas about them in general.”

Perry then cites heavily from The Nature of Order to make her point. Her selected quotations are worth reading in full.

It is easy to dismiss feelings as “subjective” and “unreliable,” and therefore not a reasonable basis for any form of scientific agreement. And of course, in private matters, where people’s feelings vary greatly from one person to the next, feelings cannot be used as a basis for agreement. However, in the domain of patterns, where people seem to agree 90, 95, even 99 percent of the time, we may treat this agreement as an extraordinary, almost shattering, discovery, about the solidity of human feelings, and we may certainly use it as scientific.

But for fear of repeating myself, I must say once again that the agreement lies only in people’s actual feelings, not in their opinions.

For example, if I take people to window places (window seats, glazed alcoves, a chair by a low windowsill looking out onto some flowers, a bay window…) and ask them to compare these window places with those windows in rooms where the windows are flat inserts into the wall, almost no one will say that the flat windows actually feel more comfortable than the window places—so we shall have as much as 95 percent agreement.

And if I take the same group of people to a variety of places which have modular wall panels in them, and compare these places with places where walls are built up from bricks, plaster, wood, paper, stone… almost none of them will say that the modular panels make them feel better, so long as I insist that I only want to know how they feel. Again, 95 percent agreement. But the moment I allow people to express their opinions, or mix their ideas and opinions with their feelings, then the agreement vanishes. Suddenly the staunch adherents of modular components, and the industries which produce them, will find all kinds of arguments to explain why modular panels are better, why they are economically necessary. And in the same way, once opinion takes over, the window places will be dismissed as impractical, the need for prefabricated windows discussed so important… all these arguments in fact fallacious, but nevertheless presented in a way which makes them seem compelling.

In short, the scientific accuracy of the patterns can only from from direct assessment of people’s feelings, not from argument or discussion.

The degree of life in any given center, relative to others, is, as I have said, objective. But in order to measure this degree of life, it is difficult to use what, in present-day science, are conventionally regarded as "objective" methods. Instead, to get practical results, we must use ourselves as measuring instruments, in a new form of measuring process which relies (necessarily) on the human observer and that observer's observation of his or her own inner state. Nevertheless, the measurement that is to be made this way is objective in the normal scientific sense…

We can always ask ourselves just how a pattern makes us feel.

And we can always ask the same of someone else. Imagine someone who proposes that modular aluminum wall panels are of great importance in the construction of houses.

Simply ask him how he feels in rooms built out of them.

He will be able to do dozens of critical experiments which “prove” that they are better, and that they make the environment better, cleaner, healthier… But the one thing he will not be able to do, if his is honest with himself, is to claim that the presence of modular panels is a distinguishing feature of the places in which he feels good.

His feeling is direct, and univocal.

It is not the same, at all, as asking someone his opinion. If I ask someone whether he approves of “parking garages” say—he may give a variety of answers. He may say, “Well it all depends what you mean.” Or he may say, “There is no avoiding them”; or he may say, “It is the best available solution to a difficult problem”... on and on.

None of this has anything to do with his feelings.

It is also not the same as asking for a person’s taste.

If I ask a person whether he likes hexagonal buildings, say, or buildings in which apartments made like shoe boxes are piled on top of one another, he may treat the question as a question about his taste. In this case he may say, “It is very inventive,” or, wishing to prove he has good taste, “Yes, this modern architecture is fascinating, isn’t it?”

Still, none of this has anything to do with his feelings.

And it is also not the same as asking what a person thinks of an idea.

Again, suppose I formulate a certain pattern, and it describes, in the problem statement, a variety of problems which a person can connect up with his philosophical leanings, his attitudes, his intellect, his ideas about the world—then he may again give me a variety of confusing answers.

He may say, “Well, I don’t agree with your formulation of this or that fact”; or he may say, “The evidence you cited on such a such a point has been debated by the best authorities”; or again, “Well, I can’t take this seriously, because if you consider its long term implications you can see that it would never do.”...

All this again, has nothing to do with his feelings.

It simply asks for feelings, and for nothing else.

Alexander was able to argue about the objectivity of a science rooted in human feelings not only by the overwhelming empirical evidence of his results, but also on account of peculiar characterization of just what role human “feeling,” as applied within his experiments with uncanny uniformity and consensus, could play as an instrument of measurement.

The degree of life in any given center, relative to others, is, as I have said, objective. But in order to measure this degree of life, it is difficult to use what, in present-day science, are conventionally regarded as “objective” methods. Instead, to get practical results, we must use ourselves as measuring instruments, in a new form of measuring process which relies (necessarily) on the human observer and that observer's observation of his or her own inner state. Nevertheless, the measurement that is to be made this way is objective in the normal scientific sense.—Christopher Alexander

In applying his ideas, Alexander had to struggle constantly just to give people permission to share their honest feelings, rather than just ad-hoc rationalizations, justifications, or opinions. Beneath their egos, he saw, people had a very consistent knack for recognizing life. They could perceive scenes and objects which demonstrated the harmony of the fifteen properties (which follows) even when they were never taught about those properties, or trained how to detect them and their interrelation. But constantly they fought this ability within themselves. Their rationalizing mind would get in their way, tying their tongue in order to sound scientific, “objective,” rational, or cultured.

The Fifteen Properties of Life

In The Nature of Order, Alexander argues that there are fifteen properties which are present within all “living” systems of centers within nature and our artificial world. He means this in the most broadly encompassing sense possible—everything in the universe consists of centers, or gestalts, which have developed out of “living” processes, the earmarks of which are these fifteen properties.

Even though we are innately able to measure the presence of life which proper coordination of these properties bestow upon sensible systems, learning to discern them individually, and their interplay, takes a great deal of perceptual training; moreso to employ them and bring them to life within one’s own design. Each is simple, but together they are complex enough to explain everything you see, hear, and touch.

Everything living has boundaries. Everything living has local symmetries and alternating repetitions of form. Everything living evinces roughness and contrast, and echoes its features across its form and through its levels of scale. Gestalts interlock within one another, like puzzle pieces, and each side presents a positive definition of space. There are voids, and there are simplicities and inner-calmness. There is good shape, gradient, and “not seperateness.” All of these features enhance living constellations of strong centers which, to our human perception, can be said to appear the most living.

These properties Alexander finds in all areas of nature, at all sizes. They are in waves and estuaries, in snail shells and leaves, in the arms of galaxies and in rocks. And paintings, rugs, pottery, ornaments and buildings from all traditions, east and west can, too, be analyzed and judged by the sensible presence of and harmony within all these mutual reinforcing properties.

Centers are the wholes about which everything organizes, so-called because they don’t necessarily have boundaries as shapes or figures do. They aren’t like physical centers of gravity, but rather exist in stress patterns within the field of their relation to other centers. Centers are recursive, and while each center can be considered a whole on its own, it also contains wholesome centers within itself, while simultaneously supporting other centers in forming greater wholes. And it is in experiencing the wholesomeness of our world, natural and human-made, that humanity finds the grounds of itself, its own base wholesomeness, the sustaining roots of life.

All the processes of nature have created, across strata, the fifteen properties within all material forms. Good human design, Alexander advises, has traditionally followed its own sense of those same processes to create human culture and human environments.

However, as he writes in The Nature of Order,

We have suffered, in the last hundred years especially, because the old roots of architecture—its sound pre-intellectual traditions—have largely disappeared, and because the lawless, arbitrary efforts to define a new architecture—a modern architecture—have been, so far, almost entirely without a coherent basis…

The essence of the problem is that we have not, as far as I know, ever yet concentrated our attention on the fact that in nature, all of the configurations that do occur belong to a relatively small subset of all the configurations that could possibly occur... In nature the principle of unfolding wholeness creates living structure nearly all the time. Human designers, who are not constrained by this unfolding, can violate the wholeness if they wish to, and can therefore create non-living structures as often as they choose.

In purely mathematical terms, the number of possibly ugly, post-modern, inhospitable architectural designs which could be created, or generated, greatly dwarf the possible number of life-sustaining, wholesome designs. This is true, just as the number of randomly generated songs, or noisy, senseless images which could come created vastly outnumber the amount of beautiful or sensible ones which make-up our cultures of music and graphic art.

By distilling and focusing on what it is which makes good building-designs wholesome, Alexander proposes a mode of perception and criticism which he sees can be extrapolated, in some way, into all domains. The ability to differentiate, quantifiably, the amount of “life” within any proposed form is his prescription for setting-right every field of human creation within society.

It may be easy for the reader to assume that what is being described here is something of a universal aesthetic; something like a guide, drawing on nature, for creating or criticizing art. Where Alexander challenges us most, however, is in his insistence in calling this system “life.” As we’ve seen, he calls it objective, and, furthermore, situates it as a science at home within the domains of physics and biology.

Verifying this is a matter for your own empirical research. The reader is invited to read Christopher Alexander, and accept his challenge in seeing the world through his eyes for a while. Putting on the glasses which reveal a perceptual world of life-giving forms, in order to evaluate first-hand the experience of a living universe, is the means by which we encourages everyone to escape the all-to-rigid appreciations of what “life” truly is as described by biology or AI theorists.

This is essential because, as Alexander observes again and again in his discussions with those who inhabit the buildings and urban areas he designed and studied, living environments facilitate human wholeness in its base form. The human subject, himself or herself, becomes wholesome and potent as an agent within a life-nourishing, living environment. Where these fifteen properties exist in mutual reinforcement, people are empowered to find themselves and their higher humanity, to become themselves again. And this goal, the restoration of common humanity, is a goal which the Living Principles Foundation seeks to work toward.

Different Conversations About Life

Christopher Alexander helps us step outside the still-current notion of life as purely a biological phenomenon, but he is of course far from the first person to propose such a larger definition. Alexander’s concept of life was largely inspired by philosopher Alfred Whitehead, who also went beyond the biological meaning.

Concerning life, ideas like this have existed throughout history.

In historic times, and in many primitive cultures, it was commonplace for people to understand that different places in the world had different degrees of life or spirit. For example, in tribal african societies and among California indians or Australian aborigines, it was common to recognize a distinction between one tree and other, one rock and another, recognizing that even though all rocks have their life, still, this rock has more life, or more spirit; or this place has a special significance.—Christopher Alexander

Although such a conception does not yet exist in modern science, it does exist in traditional Buddhism, which in many sects treats the world in such a way that every single thing “has its life.” Many animistic religions too—for example, those of African tribes, or of the Australian aborigines—treat each part of the world as having its own life and its own spirit.—Christopher Alexander

It is only in the modern tradition since the enlightenment that this notion of a living universe so homogeneously fell out of favor. Alexander fingers Descrates as the central figure inaugurating the metaphysics which presupposes the universe as a grand clock-work mechanism. Exceptions to this metaphysics have been few until late, but never zero. The modern Western tradition has still occasioned attempts to restore vitality to its cultural perception— those works in the vitalist tradition, for example, by Goethe, Hans Driesch, and most notably Henri Bergson’s L'Évolution créatrice in 1907.

Most recently, it is in Speculative Realism that one finds todays’ challenge to the Cartesian philosophy of cause and effect which characterizes Western philosophy. Illustrative of this approach is the vitalism expounded by Eugene Thacker. We’ll allow the collaborative editors at Wikipedia to provide the quickest overview.

Eugene Thacker has examined how the concept of “life itself” is both determined within regional philosophy and also how “life itself” comes to acquire metaphysical properties. His book After Life shows how the ontology of life operates by way of a split between “Life” and “the living,” making possible a “metaphysical displacement” in which life is thought via another metaphysical term, such as time, form, or spirit: "Every ontology of life thinks of life in terms of something-other-than-life...that something-other-than-life is most often a metaphysical concept, such as time and temporality, form and causality, or spirit and immanence" Thacker traces this theme from Aristotle, to Scholasticism and mysticism/negative theology, to Spinoza and Kant, showing how this three-fold displacement is also alive in philosophy today (life as time in process philosophy and Deleuzianism, life as form in biopolitical thought, life as spirit in post-secular philosophies of religion). Thacker examines the relation of speculative realism to the ontology of life, arguing for a “vitalist correlation”: “Let us say that a vitalist correlation is one that fails to conserve the correlationist dual necessity of the separation and inseparability of thought and object, self and world, and which does so based on some ontologized notion of ‘life’.'” Ultimately Thacker argues for a skepticism regarding “life”: “Life is not only a problem of philosophy, but a problem for philosophy.”

Other thinkers have emerged within this group, united in their allegiance to what has been known as “process philosophy,” rallying around such thinkers as Schelling, Bergson, Whitehead, and Deleuze, among others. A recent example is found in Steven Shaviro's book Without Criteria: Kant, Whitehead, Deleuze, and Aesthetics, which argues for a process-based approach that entails panpsychism as much as it does vitalism or animism. For Shaviro, it is Whitehead's philosophy of prehensions and nexus that offers the best combination of continental and analytical philosophy. Another recent example is found in Jane Bennett's book Vibrant Matter, which argues for a shift from human relations to things, to a “vibrant matter” that cuts across the living and non-living, human bodies and non-human bodies. Leon Niemoczynski, in his book Charles Sanders Peirce and a Religious Metaphysics of Nature, invokes what he calls "speculative naturalism" so as to argue that nature can afford lines of insight into its own infinitely productive "vibrant" ground, which he identifies as natura naturans.

Life An Alignment Tool

I ended up down a rabbit hole in Christopher Alexander’s Nature of Order, Book 2 and I need to write about it. I think it’s nothing less than a unifying theory for everything I see working in the world and everything I see failing.— David Gasca, How to make living systems

The quality of our society is largely conditioned by the quality of our invisible infrastructure. Infrastructure often means the hidden pipes and circuits and tunnels which, behind walls and screens and asphalt, splice our world together from behind.

While these affairs of our physical environments are especially important, they can only be handled once we’re on the same footing regarding our common meaning, standards and definitions. It is these which we refer to here as “invisible infrastructure.” They are the constituents of the human systems: the social patterns of organization and constructs which give us shared meaning and common goals to work toward, together.

Our key institutions, governments, providers and overseers of said infrastructure have organized a great deal of our society around a) metrics and, b) goals for those metrics. First and foremost, a great deal of infrastructure is organized around life expectancy, which is easily measured and for which goals are set. And, yet, there are no like-terms agreed upon to measure and target the quality of the time when we are expected to live for!

Let us run through the range of the many competing standards and measures:

Psychologists often use Subjective Well-Being (SWB). Life Satisfaction: Individuals rate their overall life satisfaction on a scale. We use Income and Economic Indicators: GDP per capita, personal income, and economic stability. And things like Employment and Job Satisfaction: Employment rates, job security, and job satisfaction. We use Health metrics: Life expectancy, disability rates, and overall health. And Social Indicators: Social Relationships: Quality and quantity of social connections, relationships, and support networks. We use things Environmental Quality: Air and water quality, access to green spaces, and exposure to environmental hazards. We use Cultural Indicators: Cultural Engagement: Participation in cultural and recreational activities. And things like Educational Attainment: Levels of education achieved. Educational Satisfaction: Satisfaction with the educational experience. Political Indicators: Stability of the political environment. Access to Political Rights: Access to democratic processes and political rights. Personal Safety: Crime rates, personal safety, and perceptions of safety. National Security: Security at the national level. Technology and Innovation: Access to Technology: Availability and access to modern technology. Innovation: A culture of innovation and technological advancement.

Life is, however, an objective attribute of all systems. Since life is an attribute of all these systems, and since we now have a good definition of life, are there ways to rectify all these questions toward one end? That of life itself? We are proposing nothing less than that an increase of life, defined above, become the unifying metric-as-goal for system performance and explanatory mechanism of what works and does not across all relevant systems and domains.

Non-transiant, unnatural states of decay in society are undesirable, a sentiment universally acknowledged. Does not the world collectively agree and express a common desire for a thriving environment where our children can flourish? Acknowledgment of life, and the cycle of life and death, resonate with everyone. Regardless of location or cultural background, everyone can at least identify and agree when something is biologically dead. Clarity on the opposite, being alive, is equally universal, as Alexander's empirical work reveals. This is what is new. The presence of life in its biological sense is tangible reality, we’ve long known. And yet, for all that, the larger definition of life we are grappling with here has remained elusive and confusing to this very day.

Ask around! What is the meaning of life? Despite our global interconnectedness, agreement remains elusive. Different perspectives from individuals worldwide underscore the challenge of finding a common understanding. Yet across the world, a growing number of responsible minds are acknowledging the magnitude of this problem, recognizing that without a shared understanding of life's meaning, global collaboration and the creation of a better future for our children become increasingly challenging. The quest for a universally agreed-upon meaning of life is presented as a crucial conceptual building block for collective organization and the pursuit of a vision for a flourishing world, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries.

Meeting this growing interest is the purpose of the Living Principles Foundation. We believe, across all fields, that formalizing the goal of increasing life has the potential to solve all those problems of alignment. Everyone shares this same goal implicitly; because everyone wants to build a better future for our children! Yet, sometimes it appears that misalignment increases as much as agreement. We know that the current metrics aren’t strong enough to align us. Life is.

Measuring Life

Let’s take stock of how the work of Christopher Alexander is being taken up today. Already, a wide variety of thinkers such as Niko Salingaros and Bin Jiang, Diana Olave and Dan Winter have each done work on advancing new understandings of life.

Those drawing on modern cognitive science, contributing to computational models of Alexander’s idea of life, have discovered that beauty or coherence highly correlates to the number of subsymmetries or substructures. Critical theorists can take a great deal of sympathy in Alexander’s critique of linear, stultifying determinism arising in the Western tradition, largely attributable to René Descartes. And, of course, explorers of sacred and occult traditions find a great deal of sense in Alexander’s expansions of meanings beyond the confines of modern conceptions. We believe that what seems convergent and contradictory in so broad a mix of minds needn’t be so, given organization and dialogue.

We’ll focus here only on the applications in science, since that is the field where Alexander most desired his approach to life to find its place. Jiang has demonstrated that there is a structural beauty that arises directly out of living structure or wholeness, a physical and mathematical structure that underlies all space and matter. Salingaros uses a model of organized complexity to estimate the degree of “life” in a building, a quantity that measures the organization of visual information. His model is based on an analogy with the physics of thermodynamic processes and extends earlier work by Herbert A. Simon and Warren Weaver. The terminology arises from an analogy with biological forms. Salingaros distinguished between “organized” and “unorganized” complexity, going further to claim innate (biologically based) positive advantages of the former.

Going beyond theoretical concerns, Alexander’s work is already contributing to the practical implementation of new digital environments, like the metaverse, which splice high-level virtual spaces with our embodied real world. Formalization of his ideas into computable measures of beauty are central in these affairs.

Objective beauty combines fractals with nested symmetries, together with other sources of biologically-meaningful visual information. Unconscious viewer engagement is clearly not based on intellectualizing subjective criteria. The more intense yet mathematically ordered the stimulus, the higher the degree of objective beauty. This definition is complexity-based: it outlines a beauty scale in which low values correspond either to less visual information or disordered information; while high values correspond to coherent, high-content, organized information.

What is generally agreed upon is that being alive is about being complex: forming, transforming, and maintaining a structural organization that consists of multiple constituents arranged in specific orders and patterns. The advances in the theory of complexity have come not just from biologists, but also from architects and urban theorists.

Life is scientifically verifiable, but not fully—there is more needed. Let us examine some of the historical context.

Life is now scientifically verifiable

Until recently, science was not yet in a state ready to appropriately consider or verify life as we’ve been describing it. A great deal of Christopher Alexander’s work has entailed explaining the history of science in order to explain why this is so.

The mechanistic idea of order can be traced to Descartes, around 1640. His idea was: if you want to know how something works, you can find out by pretending that it is a machine. You completely isolate the thing you are interested in—the rolling of a ball, the falling of an apple, the flowing of the blood in the human body—from everything else, and you invent a mechanical model, a mental toy, which obeys certain rules, and which will then replicate the behavior of the thing. It was because of this kind of Cartesian thought that one was able to find out how things work in the modern sense. However, the crucial thing which Descartes understood very well, but which we most often forget, is that this process is only a method. This business of isolating things, breaking them into fragments, and of making machine-like pictures (or models) of how things work, is not how reality actually is. It is a convenient mental exercise, something we do to reality, in order to understand it.

Descartes himself clearly understood his procedure as a mental trick. He was a religious person who would have been horrified to find out that people in the 20th century began to think that reality itself was actually like this. But in the years since Descartes lived, as his idea gathered momentum, and people found out that you really could understand how the bloodstream works, or how the stars are born, by seeing them as machines—and after people had used the idea to find out almost everything mechanical about the world from the 17th to 20th centuries—then, sometime in the 20th century, people shifted into a new mental state that began treating reality as if this mechanical picture really were the nature of things, as if everything really were a machine."But instead of lucid insight, instead of grow- ing communal awareness of what should be done in a building, or in a park, even on a tiny park bench— in short, of what is good—the situation remains one in which several dissimilar and in- compatible points of view are at war in some poorly understood balancing act. —- Christopher Alexander

Alexander’s account of the effects of the Enlightenment is one widely held and corroborated by many thinkers, past and present.

The invention of “science” or the scientific method in the West first arrived when “natural philosophy” supplanted the authority of the Catholic Church by provably refuting Biblical scripture through empirical evidence and replicable prediction. Rather than try to find narratives that harmonized with a prescribed doctrine of cyclical Nature, the impetus of scientific inquiry was open ended, linear, and never complete. It was Promethean in its challenge to the authority of the gods, in effect, putting the interests and curiosity of mortals above those of the “gods” or ecclesiastical authorities. This insubordinate “skepticism” accentuated the separation of man from nature. The pursuit of “truth” as explanation rather than derived from clerical authority or doctrine, eliminated any notion of absolute authority or certainty. The classic example of this is in 1623 Galileo’s publication of the Assayer, where among other claims, he argued for the heliocentric view of the Universe, where the earth rotated around the sun. This was incommensurate with the doctrine of the Catholic Church, where both Aristotelian text and Biblical script held that the sun rotated around the earth. To argue for a heliocentric view was to diminish the importance of man in the universe, and by implication, the primacy of God. Galileo was the first to make his argument in mathematics, base his conclusions on empirical observations, and to argue for the invariance of motion in different inertial frames, thereby setting the foundation for Newton’s classical mechanics. This shift was to establish a new form of “empirical authority” and “evidence”, a fundamental premise of the scientific method. It was this very independence from any form of doctrinal compliance that gave Enlightenment Science its energy, freedom, power, and eventual credibility. Very quickly this new intellectual and eventual institutional freedom resulted in a cascade of discoveries and practices with the founding of the Royal Society in London in 1660. Through the collaborations of Robert Boyle, Francis Bacon, Robert Hooke, and many other ‘free thinkers’ of the time, the influence of the Royal Society culminated in the Presidency of Sir Isaac Newton in 1703. Its motto, Nullius in Verba, “Take no one’s word for it”, appropriately expressed its commitment to facts and evidence. Once “natural philosophies” become testable and subject to the proof of counterfactuals, they not only moved the needle of verification from the “like” of metaphorical reasoning to the “is” of scientific proof. They made possible the design of material artifacts, indeed, technologies, that translated the potential of scientific findings into affordances to serve human needs and vanities. There was a clear divide between the material and the immaterial; the former being the provenance of science and the latter of metaphysics and religion. The Enlightenment focus on empirical evidence opened the door to the Western “Liberal cultural” tradition of secularism, humanism, and materialism. Indeed, to assert anything other than a material cause was to be unscientific and open to derision. Then came information theory, cybernetics, and digital and computational technologies that quickly spilled over into physics, complexity sciences, biology, and neuroscience. —Autonomous Culture Making: Sentient Media for Quantum Narratives, from Uncertainty Studios, John H. Clippinger, Ph.D. Peter Hirshberg OBE

This is a subject which has been discussed in countless many fields, to many varied conclusions. The success of expanding the scope of science, without abandoning objectivity, entails continuing these necessary conversations. The experiences, and successes, of Alexander doing so in his lifetime are invaluable toward these ends.

… In the present scientific world-view, a scientist would not be willing to consider a wave breaking on the shore as a living system. If I say to her that this breaking wave does have some life, the biologist will admonish me and say, ‘I suppose you mean that the wave contains many micro-organisms, and perhaps a couple of crabs, and that therefore it is a living system.’ But that is not what I mean at all. What I mean is that the wave itself – the system which in present-day science we have considered as a purely mechanical hydrodynamical system of moving water – has some degree of life. And what I mean, in general, is that every single part of the matter-space continuum has life in some degree, with some parts having very much less, and others having very much more.

In the 20th-century scientific conception, what we meant by life was defined chiefly by the life of an individual organism. We consider as an organism any carbon-oxygen-hydrogen-nitrogen system which is capable of reproducing itself, healing itself, and remaining stable for some particular lifetime … There are plenty of uncomfortable boundary problems: For example, is a fertilized egg alive during its first few minutes? Is a virus alive? Is a forest alive (as a whole …) …—Christopher Alexander, Nature of Order

It was only near the end of Alexander’s lifetime, during the beginning of the 21st century, where science was approaching an orientation amenable to his claims of verifiability and objectivity of the existence of life.

We do not so far have a scientific conception of this kind. In normal scientific parlance, one could not possibly call these things alive. And yet clearly they do have a vital role in the overall life of the larger systems. If we adhere to the purely mechanistic picture of life, we are stuck with preservationist adherence to ecological nature in its purest form—just as ecological purists have in fact been.

Life is in the very substance of space itself, and it is structural and objective, in terms of the underlying structure of wholeness, so it can be comprehensible from the perspective of mathematics and physics. However, by the time of publication of The Nature of Order, there was no mathematics powerful enough to capture wholeness, so Alexander used hundreds of pictures, photos and drawings from both nature and what we make or build to illustrate his thoughts. Recently, a mathematical model of wholeness has been developed, and it is capable of addressing not only why a structure is beautiful, but also how much beauty it has. The science underlying The Nature of Order is not only to understand complexity in nature and buildings—the focus of The Phenomenon of Life (Volume 1)—but also to create a greater degree of life in our surroundings, as well as in artifacts (The Process of Creating Life (Volume 2) and A Vision of a Living World (Volume 3)). Thus, the central theme of the book is not only the nature of order, but also the nature of life and beauty.— Christopher Alexander, Nature of Order

Since then, the torch of pursuing these expanded ideas has been passed on to us all. Many have taken it up already, and are making great strides. Staying abreast of developments, and sharing and integrating research is now the top priority.

… We have, it is true, begun some extrapolations of this idea of life … For example, we have somehow managed to extend the mechanistical concept of life to cover ecological systems (even though strictly speaking an ecological system is not alive, because it does not meet the definition of a self-replicating organism). We consider an ecological system … though not alive itself, certainly associated with biological life.

With the maturation of Quantum mechanics as a computational and communications technology, and genomics, synthetic and computational biology as both sciences and technologies, the division between information and matter and information and energy became less definitive. Even the role of the independent observer has come into question not only in physics through Quantum information and complexity theory, but in Bayesian statistics, Darwinian evolution, and the underpinnings of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. (Wolfram, 2023)Taken to their natural conclusion, the Free Energy Principle and Active Inference Quantum modeling of Friston, Fields and Levin imply a notion of mind that is profoundly both material and immaterial which exists in a plurality of forms and scales. What distinguishes this new kind computational “animism” from his “religious” precursors is that it is testable, hence refutable, and possibly the basis for a new science and technology of “mind” and extended cognition. There are few Western contemporary theological thinkers other than Teilhard DeChardin whose writings are compatible the new sciences and technologies. Tiellard deChardin’s notion of “the noosphere” predated and portended the invention of the Internet. His cosmology of an unfolding of ever greater complexity, interdependencies, and a blending of subject and object is quite compatible with the new sciences of information physics, computational biology, and Quantum complexity. It is especially remarkable that this Jesuit priest paleontologist, who was scorned by the scientific community and considered a heretic by the Catholics Church has now been restored by the Catholic Church and is considered a patron saint by the pioneers of the Internet, Kevin Kelly, John Perry Barlow, and Stewart Brand among others….

Michael Levin's perspective on consciousness and cognition shares some similarities with panpsychist ideas but also exhibits key differences. Avoidance of Panpsychism Label for Pragmatic Reasons: Levin is careful not to explicitly embrace panpsychism or panexperientalism, stating that such labels could be misleading and might divert attention from the research goals. However, he acknowledges the idea that consciousness is a basic and inherent property of biological organisms, including plants and unicellular organisms. He suggests that cellular and subcellular levels may represent the hypothetical basic units of consciousness. Scaling Down Cognition: Levin addresses the challenge posed to panpsychism when scaling down cognition. He suggests that intentionality and freedom, when scaled down, might align with concepts from particle physics and quantum indeterminacy. Levin proposes exploring the scaling of goals from simple, homeostatic goals at the chemical or cellular level to larger goals, such as those related to complex biological structures. Michael Levin’s ideas; In summary, while Levin's ideas share certain commonalities with panpsychism, such as the consideration of consciousness as a fundamental property and the acknowledgment of hierarchical levels of computation, he maintains a pragmatic stance in framing his research. His focus on the hierarchical nature of cognition, the relationship between ontogeny and phylogeny, and the scaling of goals from simple to complex levels distinguishes his approach from a straightforward panpsychist perspective. The emphasis is on understanding and applying these concepts in the context of biological research rather than engaging in abstract philosophical debates. —Autonomous Culture Making: Sentient Media for Quantum Narratives, from Uncertainty Studios, John H. Clippinger, Ph.D. Peter Hirshberg OBE

Instead of ad-hoc splices and deadness of post-modern architecture and anti-human technology, the radiant possibility for alignment between life across all material forms can continue to provide hope and courage for society if we take up the challenges the questions of life put to us.

The Diversity of Life

Life is a function of the demands of diversity. The ability to detect recurrent patterns or properties within living things does not limit the diversity of life—rather it enables it, in the same way that the fixed number of elements enable all the diverse molecular structures of our chemical world.

This fact is important because life is diversity: the coordinated presence of variety within particular environments, life exists to the extent that the evolving demands of diversity are met; nature's strength is in extreme diversity;

“People are talking about editing humans and making superhumans. I don’t want that. I don’t want factory produced similarly thinking physicists. That’s not my idea of a human society. That may be great for one person out of a 1,000 and that is about the right amount and the other 9999 I want them to be extremely diverse because if you look at the meaning of life it’s manifested not through one person but through the agglomeration of people of ideas, of personalities, of abilities that are extremely diverse and that I think is the secret to what makes the humans the most dominant species; but the superbly weird species that has ever been. A species that defies the laws of evolution. That chooses not to eat because they want to protest. That chooses to take their own life because they have lost their meaning. That chooses to not have children because they want to focus on their career. All of these things define the very premise that made us so superb and I think the reason for that is that evolution in humans no longer works vertically but horizontally. Evolution happens at a different level, not genetically anymore it happens at the level of ideas. The ability to share ideas across extremely different mindsets is what in essence defines the new stage of the evolutionary process.” —Manolis Kellis

At the beginning of Alexander's first book of Nature of Order, he frames his explorations of life in a universal sense straight-away. He correctly acknowledges that there is 90% of things we all have in common which we pay little or no attention to, and most of our identity and fighting, as individuals and as tribes, is caught up in arguing and defending over the last 10% of differences between us which seem, to us, to be everything there is to say about us. There is, in fact, far more in common and far more we agree on as individuals and as groups than we ever acknowledge.

Our commonalities do not limit our diversity, they enable it. And while everyone has a different definition of the meaning of life, we all recognize that life itself has inherent meaning.

Life has the diversity of meaning to align beings across ideology, politics, ethnicity, and cultures while paying respect to other biological systems. Life is the fine grained explanatory mechanism of what works and does not across systems.

Life is the means to enable us to both see that we are more productively alike and diverse than imagined and that there is no inherent meaning to life, rather life is a property itself that enables a wide diversity of meaning. Life is a handshake between those who advocate scientific thinking vs those who advocate religious thinking and covers a whole suite of concepts such as god, freedom, energy, whole, spirit, real, sorrow, struggle, flourishing, vitality, flow state, and nature.

Cognition to Zero

Down the line, questions will inevitably arise about how we think about life in the context of consciousness. One answer might be Integrated Information Theory.

The question becomes how do we measure life in a way that allows us to be truly as distributable as the number zero.

Runaway growth began with zero’s arrival to human mathematical capacities in Europe. When place value replaced Roman Numerals, and allowed arithmetic algorithms to compute easy sums of radically-large numbers, a cognitive explosion occurred. The missing element in this transformation was a sign which might represent nothing.

Said differently, Artificial Intelligence found an entity, zero, that self-amplifies positive feedback loop to accelerate its purpose of doing what it does; which actualized in disabling life; said differently, zero was the competence mechanism to enable nothing.

Zero anchored a common language with the standardization, uniformity, efficiency, and quantification needed for a verifiable and consistent framework to record and analyze data; this enabled double ledger accounting, the development of quantitative methods and the scientific method itself that led to the technology advancements, economic and scientific coordination and cross-cultural exchange that our world is built on.

Zero's introduction influenced the field of physics, enabling the quantification of physical phenomena and the formulation of mathematical laws, such as Newton's laws of motion. Zero's introduction as a numeral influenced mathematical notation and symbolism, making mathematics more accessible and standardized across different cultures. Zero's availability as a numerical foundation influenced technological innovation in engineering and architecture, contributing to the construction of more complex and efficient structures.

Zero's introduction in Europe played a pivotal role in standardizing commercial transactions, contributing to more transparent and reliable trade practices. Zero's arrival set the ground for the standardization of measurement units, leading to the creation of consistent systems of weights, lengths, and volumes for trade. Zero allowed for precise measurement and data analysis, enabling the birth of empirical science. The integration of zero into mathematical thinking revolutionized economics, paving the way for the development of quantitative methods for economic analysis and prediction—and so forth.

Future Research

We must leave this introductory essay with more questions than answers. But we can, still, leave with a small collection of many more open ends and avenues for continued exploration.

Let’s start by highlighting something cool; @DannyRaede writes on X: “I made an AI that can take any architectural photo and spit out the patterns the photo displays from ‘A Pattern Language’ by Christopher Alexander. Right now it's only via ChatGPT, working on other ways to make it active.” You can play with it here.

Here are some other assorted open questions we are asking, and areas where interesting work is being done.

- Sara Walker, at the Institute for Art and Ideas, is doing yeoman’s work in expanding the frontiers of life in biology, through the role of information processing in structural alignment.

- Has anyone in biology invested in Alexander´s work at all outside of Ramray Bhat?

- We’ve claimed above, in the section titled Life as an Alignment Tool, that a great deal of work in measuring and guiding various human systems toward prosperity can reach alignment by considering a broad, universal definition of life and what makes it flourish. How, we ask, might his idea be expanded into the question of the alignment problem in classical artificial intelligence?

- How does life and information integration theory relate to the below statement

Non-biological systems are “alive” through a form of symbiosis with biological life in which connection between biological and non-biological systems arises from the organic projection of the designer onto the system; childbirth and a pebble in a stream on one end, factory production and a plastic cup on the other.—An organism is a thermodynamic system. Consciousness may well be its informational representation in the phase space. Life can be represented, in this way, as an information exchange between the consciousness of the organism and the environment (the consciousness of the environment?) In the form of winnerless competition.—Yuri Barzov, Learning to Exist: From One to Zero and from Zero to One

- Life exists to the degree in which things fit; how well the form (the things) fits in the context (problem or situation it’s being used in)—good fit? is generally expressed through minimizing misfit between form and context or lack of intrusion or suppressionIn the above examples of life we can intrusion and suppression as blockers of life. The emergence of intrusion or suppression can be seen as a form of chaos (or maybe that life is this process of this continuous phenomena), and biological systems can be understood as an endless fight against the settlement of intrusion and suppression, which can be seen as a form of entropy. Has this been explored or quantified in any way?

- How can we measure the extent to which systems do not produce life?

- The extent to which life does not exist is that its pathogen or disease—has this ever been quantified in any way other than lacking life in non material systems?; the manufacturing plant can be understood to be a pathogen as much as the plastic cup can be understood to have been created in a manner in which it’s diseased.

- Correlation between this and Karl Friston FEP

There is intense laziness apparent in the natural world (which one might come to understand simply by watching household pets). Christopher Alexander (in The Nature of Order, Volume II, pp. 37-39) notes many disparate examples of natural “laziness” that hint at an underlying principle (in history of science, the “principle of least action”): a soap bubble minimizing surface area, Ohm’s law, the shape of a river’s meander. “Many systems do evolve in the direction that minimizes their potential energy,” he says. “The deeper problem is that we are then faced with the question, Why should the potential energy be minimized?”—Sarah Perry

- We want to ask how we can measure life in everything? What would it mean to measure life holistically? Life in a building is one thing. Life in a conversation is one thing. How about life in an abstract system, like the word ‘life,’ itself is another thing. How about life in one essay versus another?

- To observe a thing is to change that thing—this notion leveraged the first paradigm shift in cybernetics, when it was observed that governing systems do not exist outside of the systems they govern, and must include themselves within their modeling and control processes. Anything we model, then, is affected by its being modeled; once fluid processes are crystallized, growth and change are interrupted and forestalled, so as to keep the models accurate beyond their useful span. How varied are the cultural understandings of these very fundamental tenants? How can the formalization of life be kept from eradicating that which it seeks to preserve and foster? When is conceptualization liberatory, and when is it stultifying and deadening? Why don’t more concepts and models have their own self-destruct parameters included in design, and why do they linger on to haunt us? Would such a mortality as a design requirement not, paradoxically, render them more living?