DPiepgrass

Bio

I'm a senior software developer in Canada (earning ~US$70K in a good year) who, being late to the EA party, earns to give. Historically I've have a chronic lack of interest in making money; instead I've developed an unhealthy interest in foundational software that free markets don't build because their effects would consist almost entirely of positive externalities.

I dream of making the world better by improving programming languages and developer tools, but AFAIK no funding is available for this kind of work outside academia. My open-source projects can be seen at loyc.net, core.loyc.net, ungglish.loyc.net and ecsharp.net (among others).

Posts 7

Comments158

Thanks for your answer; it sounds like you basically understand the game the same way I do. Unfortunately, I can't offer useful advice, because I'm an Earning-To-Give engineer with no experience in science work, grantmaking or grant-receiving. (There's a project I'd like funding for, but haven't worked hard on pitches because I'm contractually "locked in" to my current job.)

How do you go about the "pitch"? That is, how do you try to convince EA grantmakers to give you funding? EAs tend to be interested in the most effective interventions, or at least "hits-based" interventions (ideas that have high expected value after multiplying by a low probability of success).

Now, funders should maybe also be interested in community-building funding, where a grant is given not so much because a project is likely to make an outsized difference in the world, but simply because an EA (GWWC signatory?) wants to use their expertise to do good in a specific way, and they have been unable to get funding to do so through conventional channels, without there being an apparent good reason for that (i.e. the project seems worthwhile and deserving). I don't know if there's a standard way of thinking about this question, but I've had some rejections from EA orgs myself, and I suspect it's easy for EA orgs to undervalue the EA community itself.

And of course, when it comes to African EAs in Africa, cost-effectiveness might be doubled or tripled by the low cost of living, and there is additional value to the local economy in keeping educated people in Africa rather than encouraging them to move somewhere with more grants.

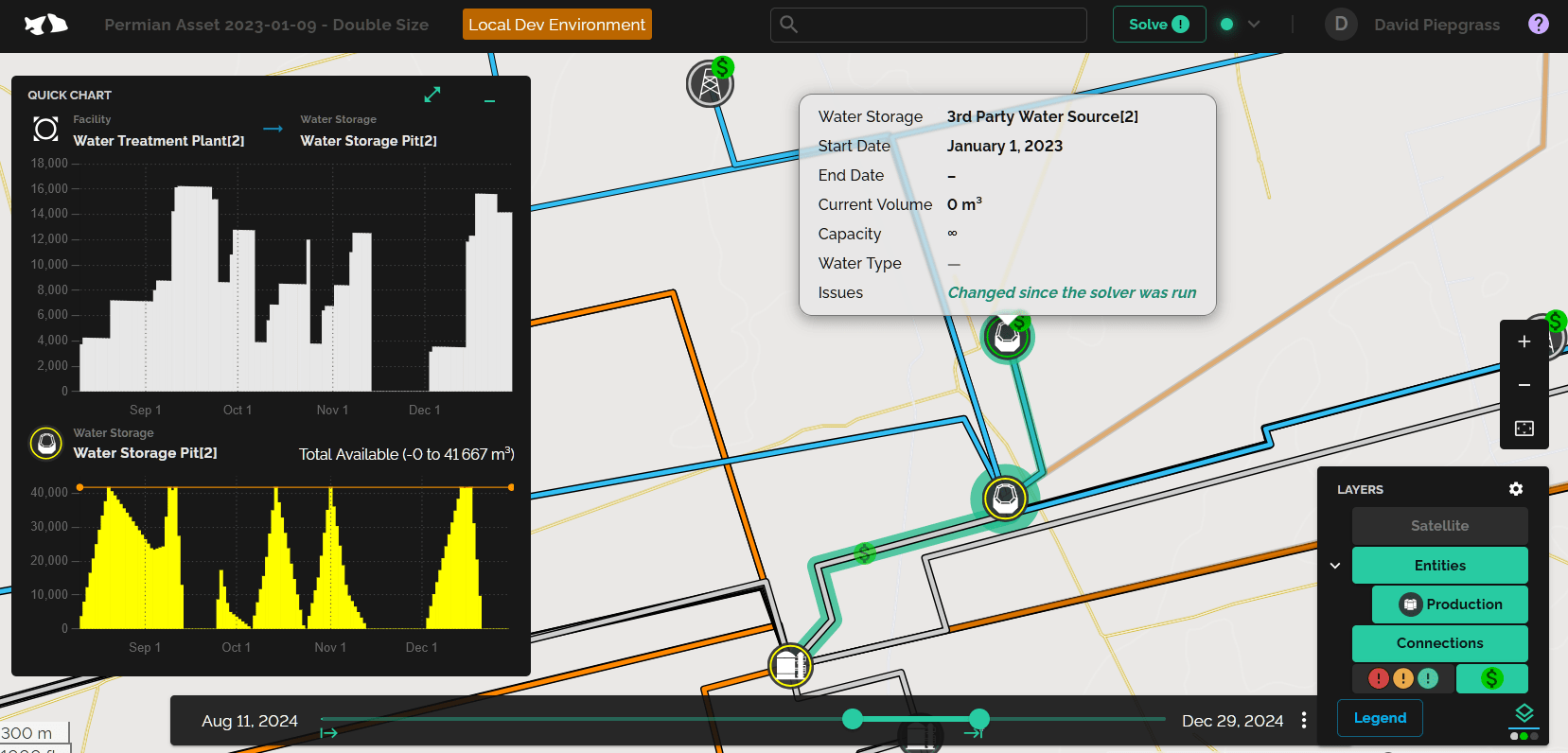

I work for a small Canadian software company that needs a new C#/TypeScript engineer. Everyone at the company normally works remote. IMO the software is not that interesting―typical Alberta software, water management for oil & gas―but our code is fairly well-factored, the frontend is pretty, and you could probably be paid to do some research into AI, and/or integrate some sort of nonlinear/MIP solver technology, or something involving hydraulic modeling.

My employer doesn't want to pay much more than the going rate for Alberta. That won't seem great to Americans, but you might snag some equity, we are near an inflection point, and we expect to grow quickly ("small business" quickly, not "startup" quickly). Intellect is a must.

Consider this job if you are strong in C# or TypeScript, you like remote, the pay is acceptable and you'd want to work with me personally (I wrote perhaps ~75% of the product).

Who am I, then? I could say many things. I'm a rationalist EA who, in the past, wrote a Super Nintendo emulator, the MilliKeys keyboard for PalmPilots, the FastNav GPS system (with turn-by-turn directions, traffic-sensitive routing, etc.), and I used to build a set of open-source projects called "Loyc". My personal page is at david.loyc.net. I am a writer with no audience and I will let you be the judge of whether this is because my writing is boring, or some other reason. YouTube must think I'm spicy, because they often censor me. Finally, I describe my approach to software here ― TL;DR: I value appropriately small code. After more than 4 years our core product―which serves three different submarkets―is about 125,000 lines of code excluding tests and blank lines. It would be less if I'd had full control of it, and 10,000 of those lines are comments ― ideally we'd have more. In my experience, many/most devs would've used 500,000 lines for this.

Our software stack includes .NET 8, EF Core, PostgreSQL, HiGHS (LP/MIP solver), Leaflet, React 18, MobX, MUI, Chart.js, Docker, ansible, Traefik, Dart (oops) and Flutter, among other things. You don't need skill in any of those, though you must be strong in C# or TypeScript, and I'm looking for multiparadigmatic competency ― e.g. you can switch between OOP and functional programming depending on what best fits the situation, or you have a knack for UX design, or something. Nice-to-haves include "vibe coding" skills (because I don't know how), sysadmin/prod/Linux skills, strong communication skills (detail, precision, and accuracy without ambiguity) and open-source contributions you can use to demo your skills.

A key implication here is that we need models of how AI will transform the world with many qualitative and quantitative details. Individual EAs working in global health, for example, cannot be expected to broadly predict how the world will change.

My view, having thought about this a fair bit, is that there is an extremely broad range of outcomes ranging from human extinction, to various dystopias, to utopia or "utopia". But there are probably a lot of effects that are relatively predictable, especially in the near term.

Of course, EAs in field X can think about how AI affects X. But this should work better after learning about whatever broad changes superforecasters (or whoever) can predict.

After following the Ukraine war closely for almost three years, I naturally also watch China's potential for military expansionism. Whereas past leaders of China talked about "forceful if necessary" reunification with Taiwan, Xi Jinping seems like a much more aggressive person, one who would actually do it―especially since the U.S. is frankly showing so much weakness in Ukraine. I know this isn't how EAs are used to thinking, but you have to start from the way dictators think. Xi, much like Putin, seems to idolize the excesses of his country's communist past, and is a conservative gambler: that is, he will take a gamble if the odds seem enough in his favor. Putin badly miscomputed his odds in Ukraine, but Russia's GDP and population were 1.843 trillion and 145 million, versus 17.8 trillion and 1.4 billion for China. At the same time, Taiwan is much less populous than Ukraine and its would-be defenders in the USA/EU/Japan are not as strong naval powers as China (yet would have to operate over a longer range). Last but not least, China is the factory of the world―if they should decide they want to do world domination military-style, they can probably do that fairly well while simultaneously selling us vital goods at suddenly-inflated prices.

So when I hear China ramped up nuclear weapon production, I immediately think of it as a nod toward Taiwan. If we don't want an invasion of Taiwan, what do we do? Liberals have a habit of magical thinking in military matters, talking of diplomacy, complaining about U.S. "war mongers", and running protests with "No Nukes" signs. But the invasion of Taiwan has nothing to do with the U.S.; Xi simply *wants* Taiwan and has the power to take it. If he makes that decision, no words can stop him. So the Free World has no role to play here other than (1) to deter and (2) to optionally help out Taiwan if Xi invades anyway.

Not all deterrents are military, of course; China and USA will surely do huge economic damage to each other if China invades, and that is a deterrent. But I think China has the upper hand here in ways the USA can't match. On paper, USA has more military spending, but for practical purposes it is the underdog in a war for Taiwan[1]. Moreover, President Xi surely noticed that all it took was a few comments from Putin about nuclear weapons to close off the possibility of a no-fly-zone in Ukraine, NATO troops on the ground, use of American weapons against Russian territory (for years), etc. So I think Xi can reasonably―and correctly―conclude that China wants Taiwan more than the USA wants to defend it. (To me at least, comments about how we can't spend more than 4% of the defense budget on Ukraine "because we need to be ready to fight China" just shows how unserious the USA is about defending democracy.) Still, USA aiding Taiwan is certainly a risk for Jinping and I think we need to make that risk look as big and scary as possible.

All this is to say that warfighting isn't the point―who knows if Trump would even bother. The point is to create a credible deterrent as part of efforts to stop the Free World from shrinking even further. If war comes, maybe we fight, maybe we don't. But war is more likely whenever dictators think they are stronger than their victims.

I would like more EAs to think seriously about containment, democracy promotion and even epistemic defenses. For what good is it to make people more healthy and prosperous, if those people later end up in a dictatorship that conscripts them or their children to fight wars―including perhaps wars against democracies? (I'm thinking especially of India and the BJP party, here. And yes, it's still good to help them despitee the risk, I'm just saying it's not enough and we should have even broader horizons.)

Granted, maybe we can't do anything. Maybe there's no tractable and cost-effective thing in this space. There are probably neglected things―like, when the Ukraine war first started, I thought Bryan Caplan's "make desertion fast" idea was good, and I wish somebody had looked at counterpropaganda operations that could've made the concept work. Still, I would like EAs to understand some things.

- The risks of geopolitics have returned―basically, cold-war stuff.

- EAs overly focus on x-risk and s-risk over catastrophic risk. Technically, c-risk is way less bad than x-risk, but it doesn't feel less bad. c-risk is more emotionally resonant for people, and risk management tasks probably overlap a lot between the two, so it's probably easier to connect with policymakers over c-risk than x-risk.

- I haven't heard EAs talk about "loss-of-influence" risk. One form of this would be AGI takeover: if AGIs are much faster, smarter and cheaper than us (whether they are controlled by humans or by themselves), a likely outcome is one in which normal humans have no control over what happens: either AGIs themselves or dictators with AGI armies make all the decisions. In this sense, it sure seems we are the hinge of history, as future humans may have no control, and past humans had an inadequate understanding of their world. But in this post I'm pointing to a more subtle loss of control, where the balance of power shifts toward dictatorships until they decide to invade democracies that are more and more distant from their sphere of influence. If global power shifts toward highly-censored strongman regimes, EAs' influence could eventually wane to zero.

- ^

just my opinion, but this video raises some of the key points

I've been thinking that there is a "fallacious, yet reasonable as a default/fallback" way to choose moral circles based on the Anthropic principle, which is closely related to my article "The Putin Fallacy―Let’s Try It Out". It's based on the idea that consciousness is "real" (part of the territory, not the map), in the same sense that quarks are real but cars are not. In this view, we say: P-zombies may be possible, but if consciousness is real (part of the territory), then by the Anthropic principle we are not P-Zombies, since P-zombies by definition do not have real experiences. (To look at it another way, P-Zombies are intelligences that do not concentrate qualia or valence, so in a solar system with P-zombies, something that experiences qualia is as likely to be found alongside one proton as any other, and there are about 10^20 times more protons in the sun as there are in the minds of everyone on Zombie Earth combined.) I also think that real qualia/valence is the fundamental object of moral value (also reasonable IMO, for why should an object with no qualia and no valence have intrinsic worth?)

By the Anthropic principle, it is reasonable to assume that whatever we happen to be is somewhat typical among beings that have qualia/valence, and thus, among beings that have moral worth. By this reasoning, it is unlikely that the sum total |W| of all qualia/valence in the world is dramatically larger than the sum total |H| of all qualia/valence among humans, because if |W| >> |H|, you and I are unlikely to find ourselves in set H. I caution people that while reasonable, this view is necessarily uncertain and thus fallacious and morally hazardous if it is treated as a certainty. Yet if we are to allocate our resources in the absence of any scientific clarity about which animals have qualia/valence, I think we should take this idea into consideration.

P.S. given the election results, I hope more people are doing now the soul-searching we should've done in 2016. I proposed my intervention "Let's Make the Truth Easier to Find" on EA Forum in March 2023. It's necessarily a partial solution, but I'm very interested to know why EAs generally weren't interested in it. I do encourage people to investigate for themselves why Mr. Post Truth himself has roughly the same popularity as the average Democrat―twice.

Also: critical feedback can be good. Even if painful, it can help a person grow. But downvotes communicate nothing to a commenter except "f**k you". So what are they good for? Text-based communication is already quite hard enough without them, and since this is a public forum I can't even tell if it's a fellow EA/rat who is voting. Maybe it's just some guy from SneerClub―but my amygdala cannot make such assumptions. Maybe there's a trick to emotional regulation, but I've never seen EA/rats work that one out, so I think the forum software shouldn't help people push other people's buttons.

I haven't seen such a resource. It would be nice.

My pet criticism of EA (forums) is that EAs seem a bit unkind, and that LWers seem a bit more unkind and often not very rationalist. I think I'm one of the most hardcore EA/rationalists you'll ever meet, but I often feel unwelcome when I dare to speak.

Like:

- I see somebody has a comment with -69 karma. An obvious outsider asking a question with some unfair assumptions about EA. Yes, it was brash and rude, but no one but me actually answered him.

- I write an article (that is not critical of any EA ideas) and, after many revisions, ask for feedback. The first two people who come along downvote it, without giving any feedback. If you downvote an article with 104 points and leave, it means you dislike it or disagree. If you downvote an article with 4 points and leave, it means you dislike it, you want the algorithm to hide it from others, you want the author to feel bad, and you don't want them to know why. If you are not aware that it makes people feel bad, you're demonstrating my point.

- I always say what I think is true and I always try to say it reasonably. But if it's critical of something, I often get downvote instead of a disagree (often without comment).

- I describe a pet idea that I've been working on for several years on LW (I built multiple web sites for it with hundreds of pages, published NuGet packages, the works). I think it works toward solving an important problem, but when I share it on LW the only people who comment say they don't like it, and sound dismissive. To their credit, they do try to explain to me why they don't like it, but they also downvote me, so I become far too distraught to try to figure out what they were trying to communicate.

- I write a critical comment (hypocrisy on my part? Maybe, but it was in response to a critical article that simply assumes the worst interpretation of what a certain community leader said, and then spends many pages discussing the implications of the obvious trueness of that assumption.) This one is weird: I get voted down to -12 with no replies, then after a few hours it's up to 16 or so. I understand this one―it was part of a battle between two factions of EA―but man that whole drama was scary. I guess that's just reflective of Bay Area or American culture, but it's scary! I don't want scary!

Look, I know I'm too thin-skinned. I was once unable to work for an entire day due to a single downvote (I asked my boss to take it from my vacation days). But wouldn't you expect an altruist to be sensitive? So, I would like us to work on being nicer, or something. Now if you'll excuse me... I don't know I'll get back into a working mood so I can get Friday's work done by Monday.

Okay, not a friendly audience after all! You guys can't say why you dislike it?

Story of my life... silent haters everywhere.

Sometimes I wonder, if Facebook groups had downvotes, would it be as bad, or worse? I mean, can EAs and rationalists muster half as much kindness as normal people for saying the kinds of things their ingroup normally says? It's not like I came in here insisting alignment is easy actually.

Notably, we have zero sway in the current administration. Arguably, most Republicans have zero sway too. Even Marco Rubio is acting like someone else, apparently to avoid being fired. I'm reminded of Prof. Gerdes, a conservative YouTuber whom I follow simply because he ends every video by saying "thank you for being the kind of person who cares about Ukraine" - which is just not something a 2025 Republican would say. Indeed, he eventually mentioned that he "just couldn't" vote for Trump a second time. I wish I could be politically powerful, but I don't even have a single EA friend. So, political donations don't seem in the cards this year.