Tobias Häberli

Posts 16

Comments144

Topic contributions1

you are threatening not to care about a problem in the world because I made you uncomfortable

Is this directed at me? Because I didn't want to do this, and I don't see why you think I did this (like, I clearly never threatened not to care about a problem?).

If I take the way that you've used "you" in your post and in the comments here seriously, you've said a bunch of things that I believe are clearly not true:

you want me to beg you to please consider it as a favor [I don't want to do this]

I know your arguments in and out. [we've never talked about this together]

you don’t care about finding out what is right [I actually do]

Now it’s about working at an AI lab or wishing you could work at an AI lab. [I don't wish to do that]

I’m already beating you and you just define the game so that the conclusion of moving toward advocacy can’t win. [we've never played any games]

you’re tedious to deal with [this one is true, but this is incidental, not sure why you know this]

I'm very sorry to hear about your dad. I hope those who would have voted for PauseAI in the donation election will consider donating to you directly.

On the points you raise, one thing stands out to me: you mention how hard it is to convince EAs that your arguments are right. But the way you've written this post (generalising about all EAs, making broad claims about their career goals, saying you're already beating them in arguments) suggests to me you're not very open to being convinced by them either. I find this sad, because I think that PauseAI is sitting in an important space (grassroots AI activism), and I'd hope the EA community & the PauseAI community could productively exchange ideas.

In cases where there is an established science or academic field or mainstream expert community, the default stance of people in EA should be nearly complete deference to expert opinion, with deference moderately decreasing only when people become properly educated (i.e., via formal education or a process approximating formal education) or credentialed in a subject.

If you took this seriously, in 2011 you'd have had no basis to trust GiveWell (quite new to charity evaluation, not strongly connected to the field, no credentials) over Charity Navigator (10 years of existence, considered mainstream experts, CEO with 30 years of experience in charity sector).

But, you could have just looked at their website (GiveWell, Charity Navigator) and tried to figure out yourself whether one of these organisations is better at evaluating charities.

I am extremely skeptical of any claim that an individual or a group is competent at assessing research in any and all extant fields of study, since this would seem to imply that individual or group possesses preternatural abilities that just aren't realistic given what we know about human limitations.

This feels like a Motte ("skeptical of any claim that an individual or a group is competent at assessing research in any and all extant fields of study") and Bailey (almost complete deference with deference only decreasing with formal education or credentials). GiveWell obviously never claimed to be experts in much beyond GHW charity evaluation.

> early critiques of GiveWell were basically "Who are you, with no background in global development or in traditional philanthropy, to think you can provide good charity evaluations?"

That seems like a perfectly reasonable, fair challenge to put to GiveWell. That’s the right question for people to ask!

I agree with this if you read the challenge literally, but the actual challenges were usually closer to a reflexive dismissal without actually engaging with GiveWell's work.

Also, I disagree that the only way we were able to build trust in GiveWell was through this:

only when people become properly educated (i.e., via formal education or a process approximating formal education) or credentialed in a subject.

We can often just look at object-level work, study research & responses to the research, and make up our mind. Credentials are often useful to navigate this, but not always necessary.

Dustin Moskovitz's net worth is $12 billion and he and Cari Tuna have pledged to give at least 50% of it away, so that's at least $6 billion.

I think this pledge is over their lifetime, not over the next 2-6 years. OP/CG seems to be spending in the realm of $1 billion per year (e.g. this, this), which would mean $2-6 billion over Austin's time frame.

lots of money will also be given to meta-EA, EA infrastructure, EA community building, EA funds, that sort of thing?

You're probably doubting this because you don't think it's a good way to spend money. But that doesn't mean that the Anthropic employees agree with you.

The not super serious answer would be: US universities are well-funded in part because rich alumni like to fund it. There might be similar reasons why Anthropic employees might want to fund EA infrastructure/community building.

If there is an influx of money into 'that sort of thing' in 2026/2027, I'd expect it to look different to the 2018-2022 spending in these areas (e.g. less general longtermist focused, more AI focused, maybe more decentralised, etc.).

Given Karnofsky’s career history, he doesn’t seem like the kind of guy to want to just outsource his family’s philanthropy to EA funds or something like that.

He was leading the Open Philanthropy arm that was primarily responsible for funding many of the things you list here:

or do you think lots of money will also be given to meta-EA, EA infrastructure, EA community building, EA funds, that sort of thing

Had Phil been listened to, then perhaps much of the FTX money would have been put aside, and things could have gone quite differently.

My understanding of what happened is different:

- Not that much of the FTX FF money was ever awarded (~$150-200million, details).

- A lot of the FTX Future Fund money could have been clawed back (I'm not sure how often this actually happened) – especially if it was unspent.

- It was sometimes voluntarily returned by EA organisations (e.g. BERI) or paid back as part of a settlement (e.g. Effective Ventures).

Thanks for this post – really would have liked having such a filter in the past.

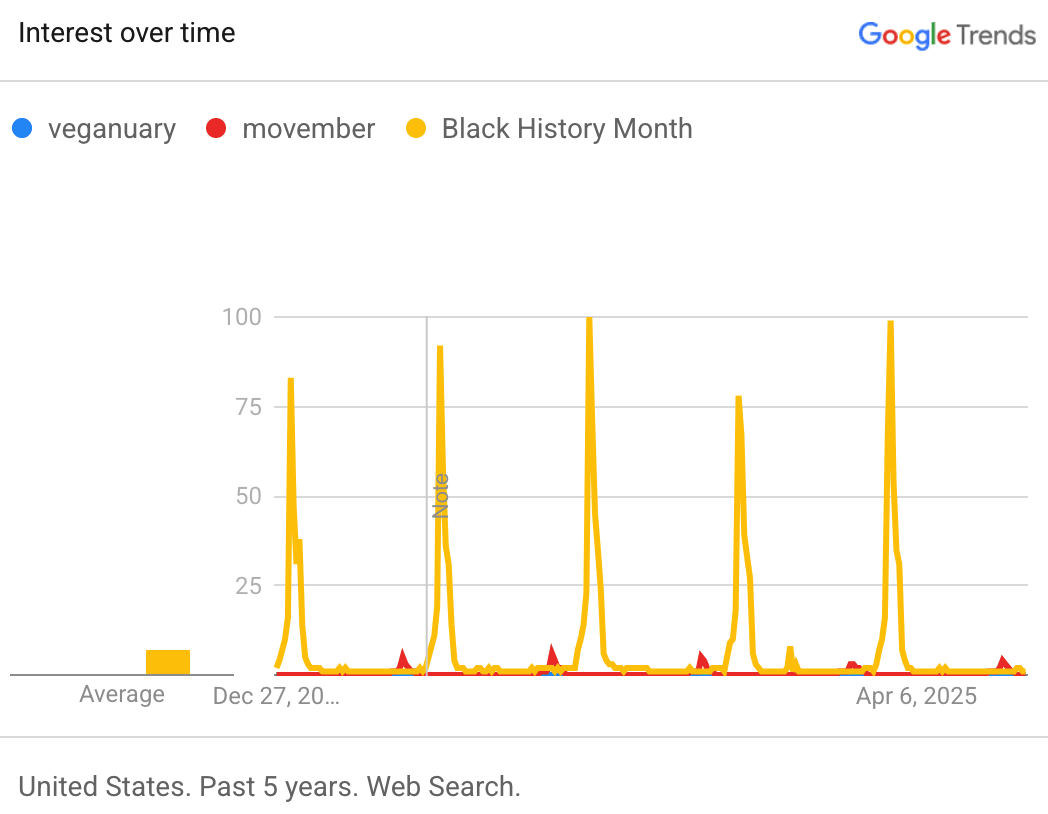

Can you say more about why you estimate this to half the convenience barrier?

I expect this to be much lower, maybe cutting the inconvenience of being vegan by 1-5%. The filter could still be worth the effort, of course :)