Good afternoon sports fans.

I'm here today to tell you a story I hope convinces you that if your own wellbeing isn't one of your top priorities, today and tomorrow and on any given Sunday, you're very likely doing it wrong.

A note on pseudo-anonymity: This is a lightly-edited transcript of a talk I gave at EA Global. As I wrote in my previous post on this topic: I’m posting this without my name but with identifying info (read on). I don’t feel a need to hide from the community, and I expect it will make a difference to some readers that I’m a senior member of staff at a famous EA org. If you want to know who I am (and update accordingly or contact me), you can easily find out. But because not everyone is as open-minded as you are, and sometimes we need to work with people very different from ourselves to achieve our goals, I want to avoid this being what shows up in searches of my name in future.

You'll never walk alone

I can't see a podium — much less stand on a podium — without thinking about the most moving thing I ever saw on a podium.

You'll Never Walk Alone was a showtune in the 40s, and then in the 60s it became the unofficial anthem of Liverpool Football Club when it was released by a Liverpudlian band, and ever since then it's been sung in their Anfield stadium before the game by tens of thousands of hard men.[1]

In 1989, a stadium disaster killed 96 Liverpool fans, many of them children. From then on, singing this song in the stadium became akin to a religious experience, a prayer for the fallen, an inspiration for the fraternity that survived. Hard men have tears in their eyes every time.

About 15 years ago my grandad died. He was the patriarch of my family, and most of them support Liverpool. At his funeral, my uncle gave the eulogy, and he tried to end it with the line, you'll never walk alone. But he couldn't bring himself to say it.

That's not the part that hit hardest though. My other uncle joined him at the podium and with his arm round his brother's shoulder he delivered the line instead, you'll never walk alone. I've never known a moment like it, you can't write scripts like that.

Since then, it's become our family anthem, not just for the Liverpool fans but for all of us, including the Arsenal fans like me. We sing it on every special occasion, weddings, funerals, birthdays, big Saturday nights, together, arms round each other's shoulders.

That close connection is what community feels like to me.

Success is a mess

And this season, in better news for my uncles, Liverpool won the Premier League, beating my team, the mighty Gunners, into second place. Regrettable.

The thing to know about this Liverpool team, though, is they lost 4 games. They conceded 41 goals. 13 times they conceded the first goal in a game. (7 times they came back to draw, 4 times they came back to win.) They were trying to win multiple competitions, and got knocked out of all the rest.

But they didn't let any of that derail their tilt at the Premier League title.

As they won more games, their odds of winning the league improved. The win probability curve went up but it wasn't smooth, it was noisy. When you zoom in, everything we eventually call success is a mix of wins and losses along the way.

Feeling invincible is fleeting

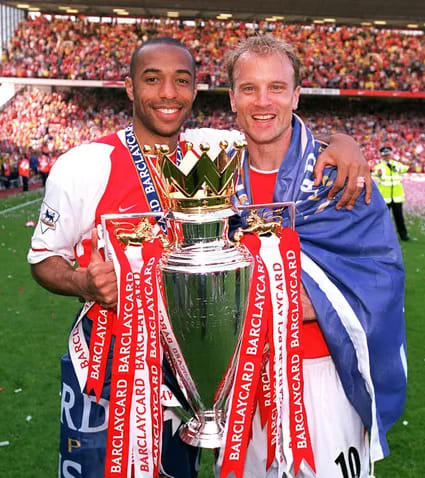

An important historical sidenote: there was one time that wasn't true, when the 2004 Arsenal team who will be known for all history as the Invincibles became the first and only team to go through a Premier League season unbeaten.

Like those legends, you and I might feel invincible for fleeting moments.

But even that team, even the Invincibles, drew 12 of their 38 league games and conceded 26 goals, and they got knocked out of the Champions League quarter finals by an inferior team because that's how the ball bounces sometimes.

And, RIP, Arsenal haven't won the Premier League in the 21 years since. Nothing lasts forever.

Gamboling through life

This is where it all started for me. I was a nerdy sports fan, one of my cool childhood nicknames was statto.

Moneyball was a major milestone in my EA journey, although I didn't know it at the time.

For those of you who misspent your youth not reading books and blogs about the analytics revolution in sport, specifically baseball, this is Brad Pitt. OK, maybe you know Brad Pitt, but this is him playing Billy Beane, who became the face of the revolution when Michael Lewis wrote a book — Moneyball — about him and how his analytical approach was getting a relatively poor team with a low wage bill to consistently beat richer teams with much higher wage bills.

(We can reflect on Michael Lewis's eye for a main character later, that man sure can see a good story coming.)

The moral of the Moneyball story is: quantification and cost-effectiveness for the win baby.

Sports have always had counting stats, but it turns out most of them are junk, if what you care about is predictably turning your limited resources into elite performance as efficiently as possible.

Moneyball, to me, was proof that spreadsheets can uncover important truths about the world in the places you'd least expect, and most care about. Proof that everything can be reduced to probability if you try hard enough. Proof that all you can do is figure out the odds, figure out what interventions might improve those odds, and then trust the process. Proof, as well, that putting this unconventional approach into practice would be controversial.

For a long time though, I was gamboling through life not in the sense that I was a sports gambler — that's my path untaken, and the path taken by my brother — but gamboling with an 'o', playful and carefree.

I spent the first decade of my career optimizing for the lowest possible levels of stress, which meant having a comfortable job and lots of time to read lots of blogs about how Liverpool were pioneers translating the Moneyball approach to soccerball, leaving in their wake the dinosaurs stuck in their old school ways. Dinosaurs like Arsenal. Don't worry though, the Banter Years are behind us, and the mighty Gunners have now seen the light.

It's not all fun and games

Which brings us to me seeing the light.

Over time I realised that while optimizing for low stress beats optimizing for a second house in France — or whatever my very stressed peers thought they were optimising for — avoiding stress isn't in fact the optimal life goal.

During the pandemic, I found both the political resistance to analytical approaches and the fact that the area under the curve was measured in the deaths of strangers more emotionally upsetting than I would have expected.

Disillusioned by my inability to do anything about that from my position in a private office in the House of Lords, I did some quiet quitting and read lots more books.

Some were about sport, naturally, but more were about work, what it is and why we do it and why even bother to begin with.

While the pandemic and our hapless policy response continued without me, I read over a hundred books, which might sound like a humblebrag, but I think the denominator matters here, because out of all of them 3 stood out: The Life You Can Save, Doing Good Better, and The Precipice.

Books about how helping others is one of the places spreadsheets can help uncover important truths.

All the sports analytics blogs had been training me for this moment, so exposure to EA ideas could make it suddenly seem obvious that I should trade my easy life for an opportunity to improve the lives of others, even if the currency of that transaction is cortisol.

A tale of 3 EA Globals

Having read the Founding Fathers, I applied for a job at CEA, and rocked up to EAG London 2022 the week before I started.

That was the beginning, peak FTX boomtimes, the whole thing was abuzz.

I expect this weekend is the first time for lots of you, and I hope you're having the experience I had of walking around going wow, this sure is a lot of cool, compassionate, collaborative people trying hard to make the world a better place together. That wasn't what other conferences I'd been to had felt like. At. All.

Fast forward to the 2023 edition, the middle of my trio, amid the aftermath of FTX's collapse. Financial, reputational and emotional damage had been done.

There was still so much good being done, still so much good to be done, but our whole endeavour felt fraught and fragile. Our confidence was shaken, that's for sure.

We were keeping on keeping on, battling to keep various crises under control, unsure whether CEA or EA would continue to exist as we knew them. CEA didn't have a CEO and I, as CEA’s Chief of Staff, and I certainly was not alone in this, was faced with a seemingly endless list of problems I didn't know how to solve.

By the time our 2024 event rolled around, to me it felt like the end, or at least the very edge.

After a year-long interim period and all its uncertainty, we'd found Zach, our new CEO, a few months earlier, and with him came renewed purpose and direction as CEA recommitted to the project of making EA the best it can be, bouncing back, building momentum.

And I sleepwalked through the event like a zombie, lost in the dark, wearing a mask. I hadn't reconciled myself with the new demands I faced, or felt I was facing. I was stuck in a rut, overwhelmed, without a way I'd practiced or proven to myself to get my balance back.

After months of chronic anxiety and insomnia, both new afflictions for me, my executive function collapsed. I couldn't make decisions or plans — not just high pressure or high stakes decisions, but which shirt to pick from the wardrobe decisions. I was scared. I struggled to admit it, I feared admitting it, but I was deeply depressed.

And so after the event, despite all the work still to do, I stopped working.

Our limits are acceptable

Happily, as much as 2024 had felt like the end for me, it wasn't. My story keeps unfolding here this year. I stopped working for 10 weeks, and during that time I stared over the edge and into the abyss. It was bleak.

Before I came back, I wanted to find ways to improve my odds of preventing this happening again. Let me tell you, prevention sure is preferable to cure.

Since coming back, as I've gained confidence in the ways I can help myself, I've been motivated to share my experience with anyone else who might be helped by it. Some of my friends and colleagues report that they have been, and that's why I want to stand up here and tell you this story too.

Before I say more, I should say my disclaimers:

- I'm an amateur, and if you need professional help you should of course speak to a professional

- There are no silver bullets or one-size-fits-all fixes, no playbook, and my number one recommendation is experiment to find what works for you

- This is not about avoiding responsibility or being less ambitious, rather it's about finding ways to make our ambitious goals achievable

The Anxiety Trap

In the months leading up to the last EAG, I was stuck in the Anxiety Trap, which is the name I've given an idea I came across in an 80k podcast episode with an evolutionary psychiatrist, Randy Nesse. The Trap lies in the gap between:

- Having impossible goals, and

- Believing it's unacceptable not to meet those goals

Stuck in between, misery lies.

To get myself out of the trap, there are 2 of my limits I'm trying hard to keep recognizing and respecting and accepting:

- My capacity, or how many minutes I can play per game, how many games I can play per season

- And my success rate, or what proportion of my shots go in, what proportion of games do I win

Limited capacity requires tradeoffs, that's a core EA principle right there. We apply it to questions like chicken or shrimp, but so many of us find it harder to apply to ourselves. It's hard to say, I could choose to do that impactful thing today, but I'm choosing instead to go swimming, or to yoga, or to touch rugby training. Choosing to do whatever it is that makes you a whole, happy, healthy person, who can come back tomorrow and the next day to carry the work on.

We have to make these tradeoffs in real time every day, and so we need to be able to say to ourselves, for now, enough is enough.

Drawing the line

Making tradeoffs is not the same as prioritization.

It starts with prioritization, writing down everything you could do or are considering doing and ranking it. But it doesn't end there.

Achieving all the impactful things one could write on a list is an impossible goal.

Hacking away at an infinite list, one task after another, creates no stopping points and still always leaves an infinitely long list at the end of the day, and for me at least, an anxiety-inducing feeling of futility.

So step 2 is taking a big fat pen and drawing a big fat line through the list — at your capacity limit.

What's above the line, for today, this week, this quarter, that's what you're working on, that's what success looks like.

What's below the line, that's set aside, maybe for someone else or some other time, or maybe just letting that particular opportunity walk on by, never to be seen again.

Respecting the line

The challenge is that respecting the limits set by my best, calmest, most considered self is hard from inside the fray, as it gets late in the day and a tired or stressed version of me has to decide whether to squeeze out just one more thing.

One way I've tried to silence the siren call of Just One More Thing is making my daily default stopping at a certain time, rather than having to decide afresh each evening, and scheduling something which requires me to not be working, something which I enjoy, which provides social support and validation from people whose relationship with me doesn't begin or end with my work or its impact.

Guess what, for me, it's usually sport, but apparently that's not for everyone, so, an opportunity to experiment and find what works for you.

Accepting what's below the line

Step 3 though, step 3 is the tricky one. Having made the list and drawn the line, step 3 is accepting what's below it won't get done, and accepting that above it success is a mess.

Even with all your focus above the line, you're still playing with probabilities, and as the problems get harder, the decisions get harder, the odds get worse, and your expected success rate goes down.

Accepting my limits doesn't come easily, at least not all the time.

My best, calmest, most considered self accepts that enough can be enough even when it isn't everything.

My best, calmest, most considered self accepts that I'm no different than successful players who miss shots or successful teams who lose games.

And yet somehow I find myself lying awake agonizing about the things I'm not doing or the mistakes I've made, and a voice saying you should be better than this, why aren't you better at this?

Acceptance takes practice, and I've been practicing, doing things that despite there being no real stakes, put me in a position where I'm not yet as proficient as I could be, and would like to be.

And guess what, it's those sports again!

When I compare myself unfavourably to all the retirees at the yoga studio who are more flexible than me, or to all the teenagers at rugby who can run our plays or read the other team's plays better than me, I try to notice the self-judgement I'm making, and to catch myself before I spiral into angst or self-criticism.

On a good day, it's obvious to me that the only thing to put in the gap between how good at rugby it's possible to be and how good at rugby I am is amusement, because it's so evidently ridiculous to expect myself to be outstanding at everything, or frankly anything, but especially hard things I've never done before.

And then my team mates are looking at me and wondering why, having just left a gap open and conceded a try, I'm laughing to myself.

Do I always live up to laughing to myself, at myself? Of course not, but with practice my success rate is going up.

Grace and Space

I practice accepting the limits of my capacity and my success rate away from the office so that when I'm at my desk and a stressor slides across my screen, I can get quickly to accepting that this might just be a problem I cannot solve immediately or alone, and consider maybe this is a problem we shouldn't try to solve at all.

The mantra I've made for myself, in collaboration with my many coaches, and which I have written in big bold letters on my whiteboard, is Grace and Space:

- Grace, to react without judgement, especially self-judgement, and

- Space, to pause, breathe, and smile, within seven seconds or less

It's a play on pace and space, the name for the style of play that dominates NBA basketball in the analytics era, which was pioneered by a mid-2000s Phoenix Suns team whose run-and-gun style earned them the nickname the 7 Seconds or Less Suns.

And this is Tyrese Haliburton. The Indiana Pacers team shaped around him and currently on a miracle run to the NBA Finals are poster children for the spreadsheet revolution. They're the spiritual stylistic successors to those 7 Seconds or Less Suns, and with a roster of players acquired cheaply, cost-effectively, from teams who under-valued them because their impact only showed up in the numbers if you knew the right places to look.

Tyrese was one of those players, identified by the Pacers as under-valued and under-utilized by his previous team, and immediately entrusted with a much more prominent role. He hit his stride running, quickly transforming the Pacers into one of the most efficient offenses in NBA history, and raising expectations.

And then, some setbacks. A lost playoff series, a hamstring injury, a cold streak, very public criticism. In mid-2024, he's since said publicly, overmatched by the expectations he had for himself, he suffered a crisis of confidence, afraid of failure for the first time, he couldn't look at himself in the mirror, didn't want to go to work.

Two details of his story stood out to me:

- His coach, to help this highly capable player, this highly ambitious person, rediscover himself, would send him the Japanese character for "acceptable" as pre-game priming

- And the second thing that stood out was how for a long time he didn't tell anyone how he was feeling, because vulnerability seemed incompatible with his idea of strength and strong leadership

Keep Your Community Close

As with Tyrese, so with me. Part of my professional identity was staying strong, being a stress absorber, not a source of stress for others. It was only when I'd blown by my limits, when I felt forced by my inability to continue working, and my fear of what would happen if I did, that I confided in my colleagues. That was — and I say this without judgement of past me — a mistake.

I admire Tyrese for choosing to use his moment in the limelight to tell a story that might make speaking up a little easier for others.[2] I hope me telling my story might make it a little easier for you to seek support drawing the line and accepting enough is enough, accepting success is a mess.

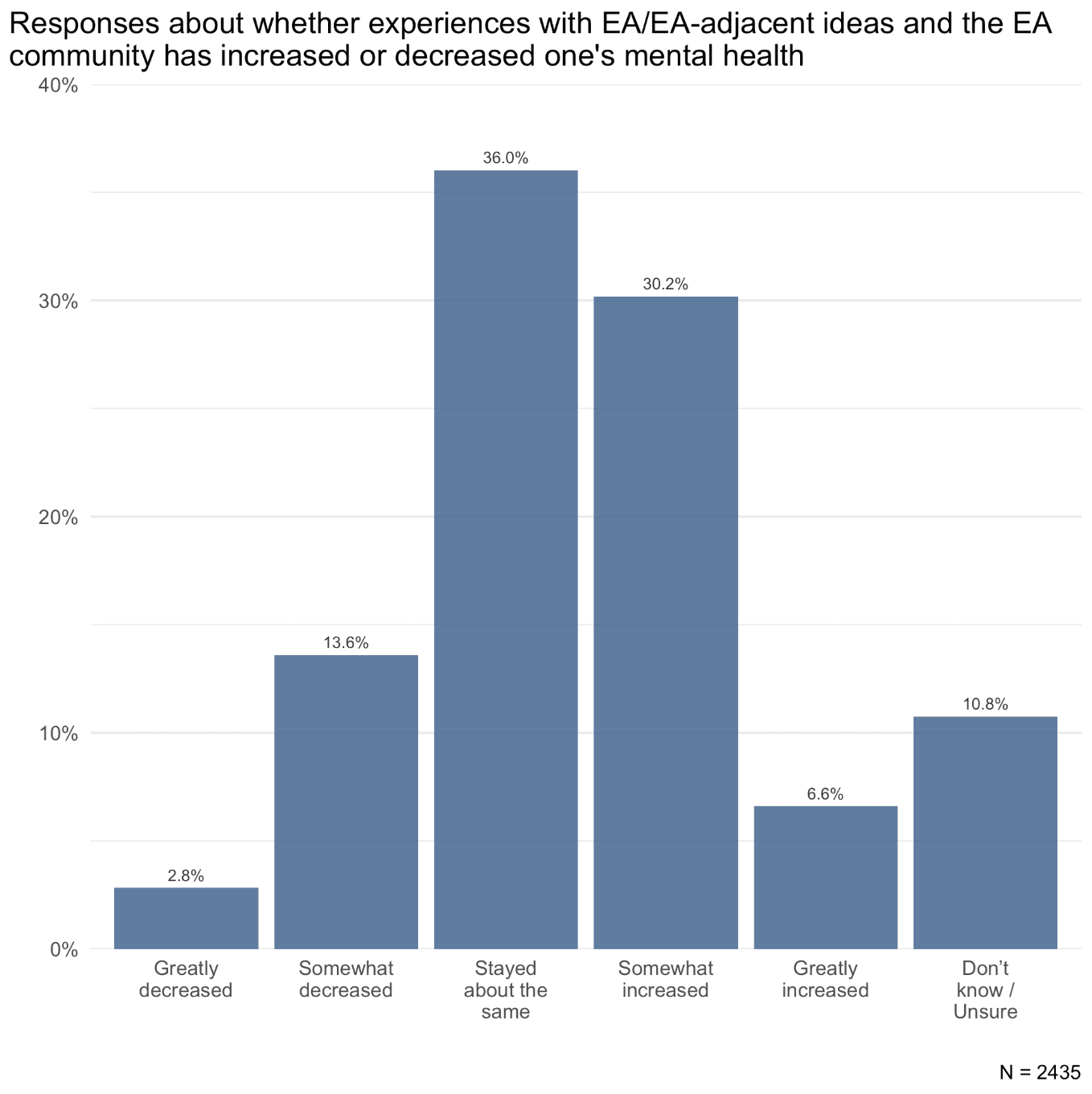

I've talked today about my experience straying onto the left hand side of this chart, my experience struggling to make an impact without making a martyr of my mental health.

Doing hard things is hard. We hold ourselves to high standards, we can see clearly the high stakes, the suffering of others we are trying to prevent, and we are always in triage. Trying to solve the world's most pressing problems makes us susceptible to setting impossible goals and believing it's unacceptable not to meet them, and we should be conscious of that.

In this context, if your own wellbeing isn't one of your top priorities today and tomorrow, on any given Sunday and any given Monday, you're very likely doing it wrong.

It's ok to act as though you can only do what you can do. It's futile to pretend otherwise. It's ok to be an EA who can clock off and switch off and sleep sweetly before the world is saved.

It's necessary to be an EA that way, because solving hard problems takes time, so it's necessary to stay on top of your game, to be able to be a whole, happy, healthy person who can keep coming to work tomorrow and next week and next month and next year.

But reading Tyrese's story recently was a reminder that stories like mine are not specifically EA stories, or crisis response stories. All sorts of people in all walks of life are falling in the same trap.

And according to the best evidence we have, there are many more people on the right hand side of this chart than the left. EA is associated with good or neutral wellbeing outcomes for most people who engage with it.

Some of the strongest predictors of good mental health are social connection and a sense of purpose. Putting these together to create a shared purpose is one of the great strengths of the EA community. We're on the same team.

Together, we can make our extraordinary efforts sustainable. Together, we can continue to make what I think of as well-calibrated cortisol sacrifices at the altar of impact, but none of us should be martyrs.

We're fortunate to be part of a community filled with wise and compassionate people. I'm fortunate to count some of them among my many coaches, and so could you, when you start the conversation.

I hope you never end up in the Trap I did, but if you do, don't make the same mistake I did. Don't suffer in silence.

Being part of our community means you never need to walk alone.

Thank you.

- ^

After my talk a wonderful human recommended to me the Anthropocene Reviewed podcast episode about YNWA. Our algorithmic friends were asleep at the wheel not having recommended it to me before. I recommend it to you.

- ^

The coda to this story is scarcely believable. I gave my talk the day after Game 1 of the best-of-7 NBA Finals, in which the underdog Pacers beat the juggernaut Oklahoma City Thunder 111-110 on yet another Tyrese last-second game-winner. (He hit 4 of these in 4 playoff series, full glitch-in-the-matrix-type stuff.) An epic Finals went all the way to Game 7 in OKC. Tyrese tore up the first quarter, nonchalantly hitting 3 long-range 3-pointers in 90 seconds. And then he tore his fcking Achilles. In the biggest moment of his life, he lay face down and pounded the hardwood. Scriptwriters would be laughed out the studio if they wrote the first 3 minutes of this.