This essay was submitted to Open Philanthropy's Cause Exploration Prizes contest.

If you're seeing this in summer 2022, we'll be posting many submissions in a short period. If you want to stop seeing them so often, apply a filter for the appropriate tag!

1. In a Nutshell

1.1. What is the problem?

Childhood sexual abuse is a common, preventable global problem associated with long-term negative outcomes for the victim and society. Current preventative strategies are uncoordinated and underfunded. A global effort to reduce childhood sexual abuse as a public health issue is needed.

1.2. What are possible interventions?

Open philanthropy may consider funding: (i) research into the prevention of childhood sexual abuse by targeting men who are sexually attracted to children; (ii) lobbying for more coordinated law enforcement response to childhood sexual abuse; (iii) lobbying to make child marriage illegal; (iv) lobbying for online childhood sexual abuse imagery to be tackled by tech companies; (v) building an academic field dedicated to the prevention of child sexual abuse.

1.3. Who else is working on this?

The main grant-maker funding this area is the Oak Foundation who awarded $61 million in grants in 2021, focussing on interventions that are effective and scalable. Open Philanthropy would need to ensure it can add unique value over and above these efforts.

2. Importance

2.1. Definition and prevalence of childhood sexual abuse

Childhood sexual abuse is broadly defined by UNICEF as any sexual activity imposed by an adult on a child (under the age of 18 years) against which the child is entitled to protection by criminal law.[1] It encompasses: (i) coercion to engage in harmful sexual activity; (ii) commercial sexual exploitation; (iii) images of child sexual abuse; (iv) child prostitution, sexual slavery, sexual trafficking, sale of children for sexual purposes and forced marriage. Some studies take a narrower definition of sexual abuse, including only forced intercourse or touching (sometimes called ‘contact’ abuse) and restricting the definition to children to those under 15 years old.

The global prevalence of childhood sexual abuse is difficult to measure with significant variation between studies. Two independent meta-analyses of sexual abuse perpetrated against female children calculated a prevalence of roughly 25%.[2][3] This proportion is higher than a previous meta-analysis, which calculated a prevalence of 16.4% - 19.7% in girls and of 6.8% - 8.8% in boys.[4] Highest rates were found for girls in Australia and for boys in Africa, with Asia having the lowest rates for both genders.[4]

Worldwide, UNICEF estimates that 120 million girls (more than 10%) have experienced forced intercourse or other forced sexual acts.[1] This is consistent with a previous meta-analysis estimating that 9% of girls and 3% of boys experienced forced sexual intercourse.[5]

There are methodological considerations when determining the true prevalence. It has been argued that childhood sexual abuse reported in retrospect when participants are in adulthood is more reliable (due to children being too embarrassed to report). While this may be true, it also introduces a source of recall bias, with potentially a long time lag from the exposure to it being measured.

I believe a conservative estimate for the prevalence of any sexual abuse in childhood would be 10-20% for girls and 5-8% for boys. My sense is that reported figures are more likely to be an underestimation, with a substantial number of victims not willing to disclose their abuse. My lower bound estimate for the prevalence of ‘contact’ sexual abuse, would be 5% for girls and 1% for boys.

2.2. Child marriage

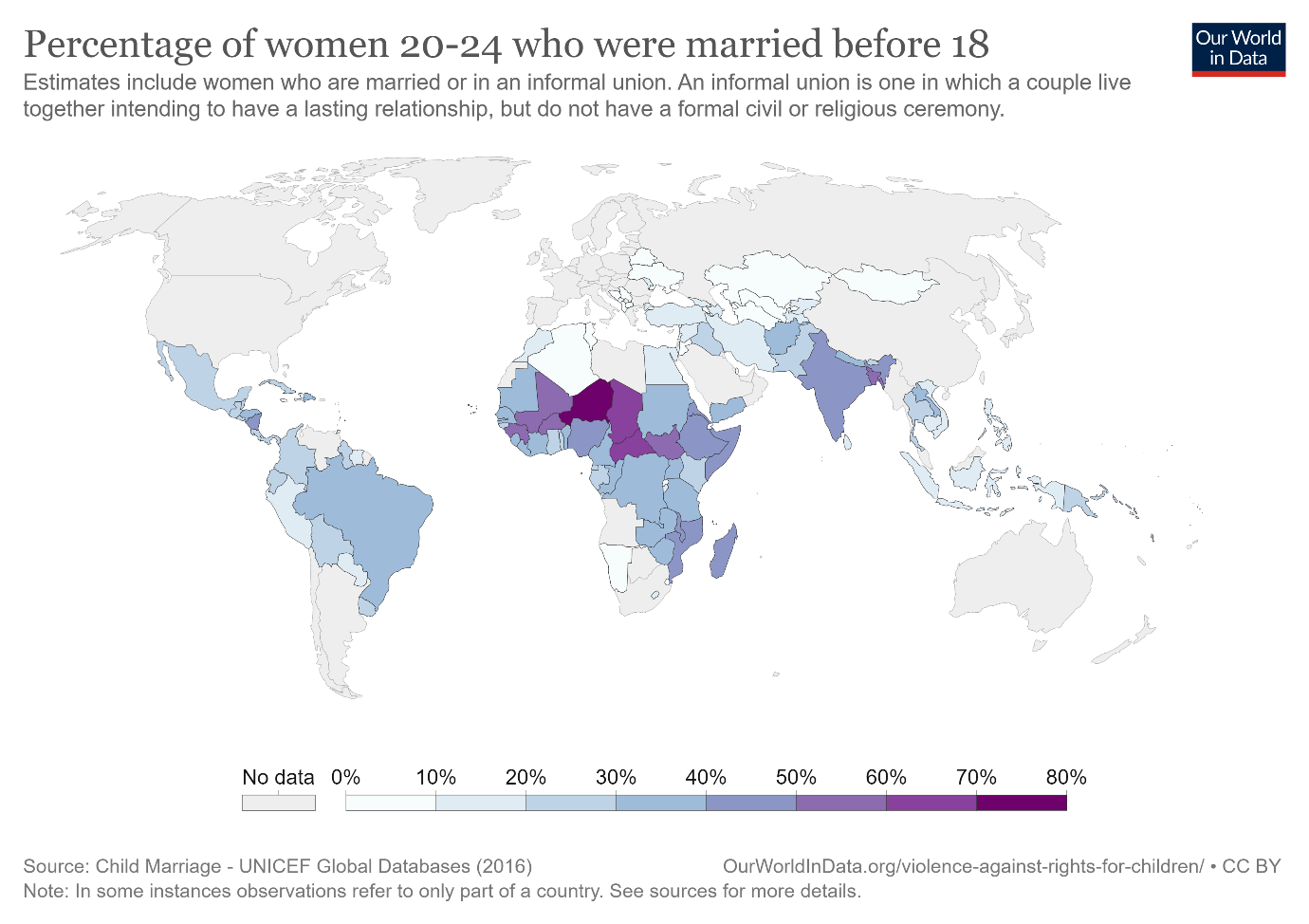

Child marriage is legal in many countries and is common in parts of the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa as shown in Figure 1. There are obvious gradations to this issue; a girl marrying at the age of 17 is quite different from one marrying before the age of 15. In sub-Saharan Africa, between 2015 and 2021, more than 10% of girls were married before their fifteenth birthday.[6]

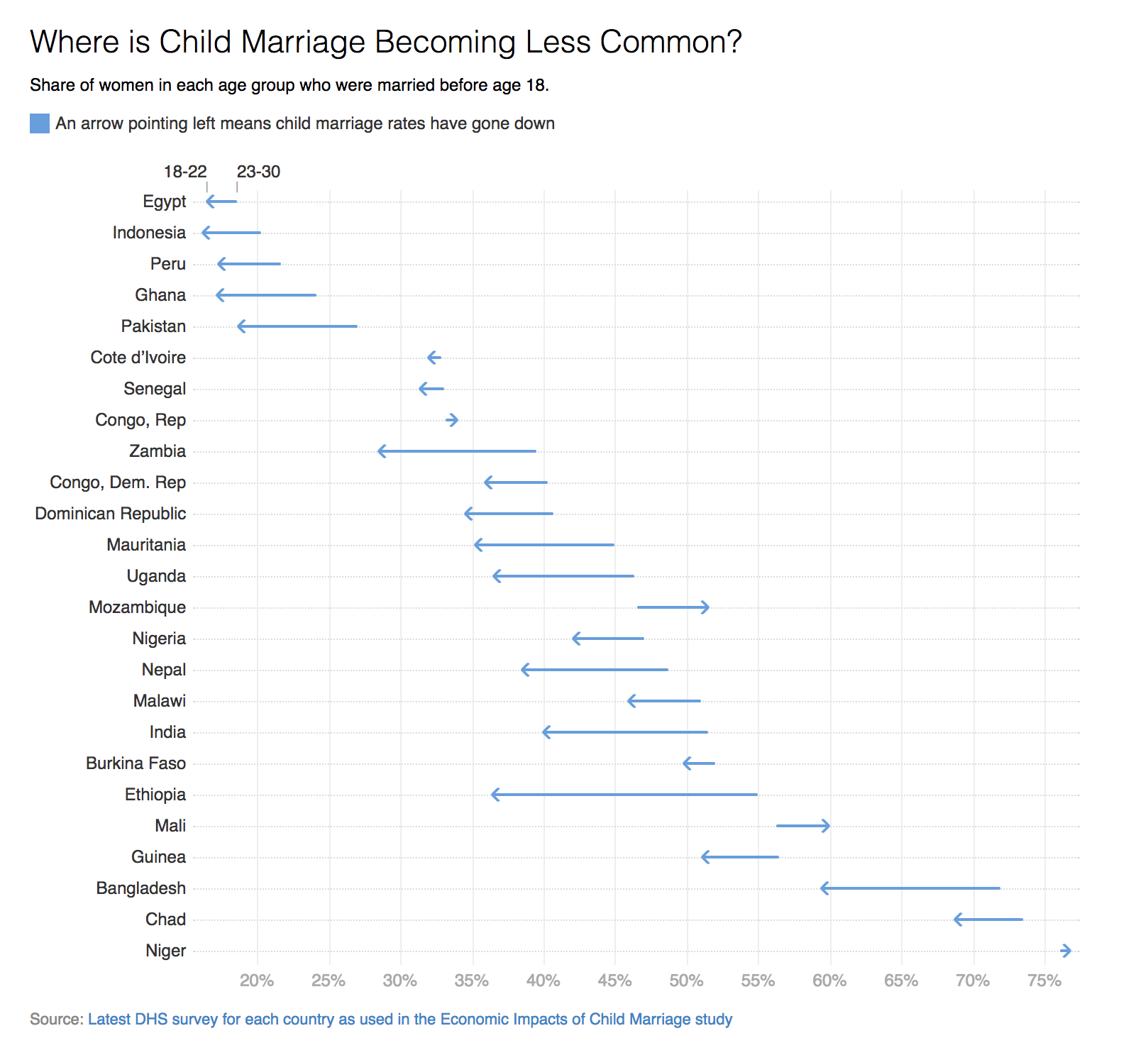

More than legitimising sexual activity with a child, these marriages are associated with loss of education, increased risk of domestic violence and are gender-based discrimination. In countries where this practice is common, there has been a promising reduction over the last few years, as shown in Figure 2. This may be partly attributable to a campaign by UNICEF. Globally, the overall prevalence has decreased over the past ten years from one in four girls to one in five today.[6]

2.3. Online child sexual abuse imagery

Another indication of the scale of this problem is in the rise of online imagery of abuse. These videos and photos are a permanent record of crimes against children and survivors report being revictimized by their distribution.[7] This has risen exponentially due to the widespread availability of broadband internet, smartphone cameras and file sharing sites.

In 1998, there were approximately 3000 reports of child sexual abuse imagery.[8] In 2014, this surpassed 1 million reports. By 2018, 45 million photos and videos were flagged by tech companies as child sex abuse imagery. By 2019, 70 million pieces of content were reported.

Facebook has been responsible for 90% of reports of child sexual abuse imagery.[8] The reason behind this is simply that Facebook scans all images that are uploaded through its site, so are detecting it more than other encrypted services. In this way, they are an industry leader in the detection and reporting of this content. By comparison Apple (with encrypts iMessage) sent 43 reports in 2018. There is now widespread concern and campaigns against the encryption of Facebook messenger.[9] AWS do not try to detect child sexual abuse imagery; Apple does not scan cloud storage.[7] Dropbox, Google and Microsoft only scan for illegal images when these are shared but not when images are uploaded. Snapchat and Yahoo scan for photos but not videos.

The National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children operates a Cybertipline which has received over 82 million reports.[10] They have reviewed over 322 million images and videos to locate victims, with over 19,100 children identified. Over time, there is a trend towards more egregious sexual content. Actively traded cases were associated with more extreme content and prepubescent victims. Girls are most often the victims, though boys are more likely to be subjected to extreme abuse.

An Interpol analysis of the International Child Sexual Exploitation Database, which contains over one million media files, was released in 2018.[11] Of these, 466,000 depicted identified children while 615,150 were of unidentified children. In this dataset, the most common age of victims was prepubescent (56%), followed by pubescent (25.4%), and infants/toddlers (4.3%).

To aid identification of victims, Interpol strongly recommends increasing resources to law enforcement.[11] The lack of resources reduces the potential for victim identification worldwide. Interpol also recommends harmonisation approaches across countries and jurisdictions, and interconnection of law enforcement databases worldwide. Convicted offenders are thought to constitute the ‘tip of the iceberg’, with many more unidentified victims that never come to the attention of law enforcement.

There is clearly a balance between online privacy and detection of child sexual abuse images. One proposed compromise would be to ‘finger-print’ images before messages are encrypted and match this to databases of known childhood sexual abuse imagery. However, these types of technological solutions do not seem to be a priority of tech companies and would require external pressure.

2.4. The long-term impact on the victim

An umbrella review (a systematic review of meta-analyses) found associations between childhood sexual abuse and a host of negative health and social outcomes in adulthood.[12] Of the 28 outcomes examined, a significant association was shown in 26, see Figure 3 for the strength of associations.

Figure 3. Risk estimates of long-term outcomes following childhood sexual abuse, from Hailes et al.[12] licensed under CC-BY

The authors also estimated the Population Attributable Fraction; the cases of a particular disease or condition that is attributable to the risk factor. These were calculated using a conservative estimate of 10% prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and are shown in Table 1. The highest association was for sexual offending versus non-sexual offending, conversion disorder (otherwise known as functional neurological disorder), borderline personality disorder, anxiety, and depression.

The Population Attributable Fraction assumes that the exposure (in this case, sexual abuse) is causative, which might not necessarily be the case. Another caveat to these findings is the possibility of confounding by other factors, which were not adjusted for in the analysis. Furthermore, the quality of evidence was generally low, with only high-quality meta-analyses for substance misuse and PTSD.

Table 1. Population attributable risk factors for various long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse, adapted from Hailes et al.[12]

| Outcome | Population attributable fraction | 95% confidence interval |

| Psychosocial outcomes | ||

| Unprotected sexual intercourse | 1·7% | 0·7–3·3 |

| Sex work | 4·5% | 2·1–7·3 |

| Sex with multiple partners | 4·8% | 2·1–8·2 |

| Substance misuse | 5·8% | 2·1–10·0 |

| Suicide attempts | 6·9% | 5·3–8·3 |

| Adult sexual revictimisation | 6·9% | 4·5–9·7 |

| Sex offending against children versus adults | 7·3% | 3·0–12·4 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 9·7% | 8·2–11·4 |

| Sex offending versus non-sex offending | 14·7% | 9·6–19·9 |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | ||

| Schizophrenia | 3·0% | 1·8–9·4 |

| Somatoform disorders | 6·9% | 1·8–18·8 |

| Eating disorders | 9·0% | 6·2–12·0 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 9·6% | 4·8–15·0 |

| Depression | 11·4% | 9·8–12·9 |

| Anxiety | 11·7% | 7·8–15·8 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 12·4% | 10·4–14·4 |

| Conversion disorder | 14·4% | 8·8–19·9 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | ||

| Psychosis | 9·8% | 7·4–12·4 |

| Post-traumatic stress responses | 10·9% | 9·9–12·7 |

| Anxiety symptomatology | 7·3% | 6·9–7·8 |

| Depressive symptomatology | 7·3% | 6·9–7·8 |

| Somatisation | 4·5% | 2·5–6·6 |

| Psychological symptoms | 5·7% | 4·0–7·8 |

| Physical health outcomes | ||

| Obesity | 3·6% | 2·3–5·0 |

| HIV | 4·4% | 1·9–7·2 |

| Pain (continuous) | 7·8% | 2·6–13·1 |

| Pain (categorical) | 5·2% | 3·8–6·7 |

| Fibromyalgia | 7·2% | 3·0–11·8 |

2.5. Cost to the economy

The lifetime economic costs of non-fatal substantiated child abuse (not limited to sexual abuse), in the USA was estimated at $122 billion in 2010 (roughly $166 billion today), based on 579,000 victims and $210,012 total economic costs per victim.[13] These costs comprised of productivity loss, healthcare, child welfare and criminal justice costs, with the biggest contributor being productivity costs.

Assuming a 10% prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in the current USA population of 329.5 million, we would expect 329,500 victims of childhood sexual abuse. Therefore, I estimate the total lifetime economic cost of childhood sexual abuse in the USA may be around $69 billion based on 2010 values ($93 billion today).

In another study, Fang et al.[14] estimated the economic cost of child abuse in East Asia and the Pacific to exceed $160 billion (in 2004 dollars) based on economic losses due to death, disease, and health risk behaviours attributable to child abuse, this is equivalent to $251 billion today.

A 2019 economic analysis of the cost of childhood sexual abuse to the US, calculated this as $9.3 billion.[15] However, this is based on 40,387 new substantiated cases of non-fatal childhood sexual abuse and 20 substantiated cases of fatal childhood sexual abuse. Substantiated cases of sexual abuse are likely to be a gross underestimation of the true prevalence. Substantiated cases of sexual abuse have a prevalence of 1%, approximately a factor of ten less than my conservative estimate of sexual abuse prevalence.

In rough equivalence to my estimation, the economic cost of contact child sexual abuse in England and Wales (population 60 million) was estimated at £10.1 billion in 2019 ($12.25 billion US dollars).[16] By including only contact child sexual abuse (exclude victims of purely online exploitation) they estimated a yearly prevalence of 2.3%.

2.6. Disability Associated Life Years

The number of DALYS lost to childhood sexual abuse was estimated by a study funded by the Gates Foundation,[17] which examined global risk factors for disease. The authors do not give a clear number of DALYS for childhood sexual abuse in the article or supplementary material. However, the combination of childhood sexual abuse and bullying accounted for <0.5% of the global attributable DALYS for males and females. I believe this is an under-estimation, as DALYS were only calculated based on childhood sexual abuse being a risk factor for depression and alcohol use disorder, whereas (as described above) it is likely to be a risk factor for a wide range of negative outcomes.

A separate Lancet study by Bellis et al.[18] examined the health consequences of all adverse childhood experiences (including but not exclusive to sexual abuse) in Europe and North America. They estimated that these adverse experiences in total resulted in 37.5 million DALYS per annum. Reducing the number of children exposed to adverse events by 10%, was estimated to result in annual savings of 3 million DALYS.

I believe that reducing the number of children exposed to adverse events by 10%, through reducing sexual abuse is a realistic target. To meet Open Philanthropy’s current bar which values one DALY at $100,000 and expects 1000x return per dollar spent, I estimate that the cost of this would have to be less than $300 million per annum. One problem with this estimation, is that measuring the global impact of changes is likely to take many years and, as stated, the primary outcome of childhood sexual abuse is subject to wide variability in its measurement.

2.7. Definition and prevalence of paedophilia

It is an uncomfortable fact that a proportion of men are sexually attracted to children (the proportion of women is small to negligible). Diagnostic classification through DSM V, defines men attracted to pre-pubescent children as paedophiles and those attracted to pubescent children as hebephiles.[19]

The consensus is that this attraction is immutable and inherent within the individual; that is to say, as with other sexual orientations, it cannot be altered.[20] Such a sexual preference manifests in puberty/early adulthood and remains stable throughout life.

Treatment does exist to reduce sexual drive and to increase empathy with victims, which will be discussed in more detail below. While not all sexual abusers of children would be classified as paedophiles or hebephiles, these conditions are inherently linked.

While any sexual contact with a child or viewing of child sexual imagery is a crime, being sexually attracted to children is not a choice. It is also true that sexual attraction does not necessarily result in criminal acts. Indeed, there are online communities of men attracted to children dedicated to them avoiding acting on these impulses.[21]

The true prevalence of paedophilia is even more difficult to measure than child sexual abuse. One systematic review put the prevalence of sexual interest in children between 2% and 24%.[22] Another expert puts the upper limit for the prevalence of paedophilia at 5%.[20]

A potential mechanism for reducing child sexual abuse is targeting men who are attracted to children, the vast majority of whom will be undetected by the criminal justice system.

2.8. Unmeasured costs

The above estimations on the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and its costs have a wide range of uncertainty. However, I believe the above data can only ever capture part of the impact of childhood sexual abuse. The emotional pain of a child going through this abuse is difficult to quantify but cannot be dismissed. Furthermore, the revictimisation of abuse survivors through the online trading and consumption of abuse imagery is not a cost I have measured but is also a nontrivial consequence of the status quo.

I believe there is an ethical obligation of a society to acknowledge this abuse exists and take steps to tackle it. I believe society would be better for having online spaces with substantially reduced availability and trading of child sex abuse imagery.

3. Tractability

There are number of potential interventions that could reduce the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse. Most of these have preliminary evidence at best. They are likely to be most effective as part of a coordinated, global strategy. Before this can reasonably be undertaken, the effectiveness and scalability of the interventions need further evaluation.

3.1. Pharmacological

A summary of pharmacological interventions is given in Table 2, mainly taken from a recent systematic review for paedophilic disorder and compulsive sexual behaviour disorder.[23] In total, 12 randomised controlled trials were identified. The studies were universally small and can only be considered preliminary.

Table 2 Summary of pharmacological interventions with at least one randomised controlled trial from Landgren et al.[23]

| Intervention | Mechanism of action | Level of evidence | Comments |

| Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone antagonists | Competitively blocks GnRH receptor, immediate reduction in luteinising hormone and follicle stimulating hormone - rapid decrease in testosterone | One well conducted positive randomised controlled trial (n=52) in men at risk of offending[24] | Promising, theoretically may avoid risk of testosterone rise associated with GnRH analogues, given as injection, possible side-effect of increased suicidal ideation |

| Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone analogues | Initial rise in testosterone but then continuous stimulation causes a downregulation of the GnRH receptor, suppressing luteinising hormone and follicle stimulating hormone | One very small crossover trial (n=5) suggesting decreased sexual response[25] | Given as injection, note initial increase of testosterone could potentially increase risk |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Binds to progesterone receptors, inhibits secretion of GnRH and ultimately reduces testosterone levels | Four small low quality trials[26][27][28][29] | Given as injection, depression is common side effect |

| Cyproterone acetate | Competitive inhibitor on the androgen receptor, decreases luteinising hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, reduces effects of GnRH | Four small low quality trials[30][31][32][29] | Oral tablet, feminising side-effects |

| Ethinylestradiol | Suppresses gonadotropin secretion, reducing testosterone production | One small trial in convicted offenders[33] | Oral tablet, feminising side-effects |

| Selective Serotonin Reuptake inhibitors | Inhibits reuptake of serotonin at the synapse, this effect on sexual drive is complex, but sexual dysfunction is a relatively common side-effect | One trial for compulsive sexual behaviours, suggests it can reduce sex drive[34] | Well tolerated, may treat concurrent depression and compulsive behaviour but not reliable in reducing sex drive |

| Antipsychotics with high D2 receptor affinity | Blockage of dopamine at the D2 receptor, results in hyperprolactinaemia and suppression of gonadotrophins | One trial suggests a weak effect[35] | Can be given as injection, potential intervention particularly if comorbid psychotic symptoms, measurement of prolactin gives good indication of sex drive suppression |

The ability to suppress the male sexual drive through suppression of testosterone is well established and can be achieved through a range of interventions. This is standard therapy for other conditions that are driven by testosterone, such as prostate cancer.[36]

There are major uncertainties about how this would work in practice as summarised below:

- Are men who suffer unwanted attraction to children willing to engage with pharmacological treatment, prior to criminal conviction? There is some evidence that a proportion of men would take this option, based on pilot studies in Germany[37] and Sweden.[24]

- If engaged in this treatment, are men actually less likely to commit offences against children? Testosterone suppression can reduce sex drive and sexual activity, and is therefore likely to reduce consumption of child sex imagery. Whether this would also reduce the risk of contact sexual offences against children is not known and may hinge on whether this type of offender can be engaged with treatment.

- Is suppression of testosterone acceptable/tolerable? There are recognised side-effects, most notably depressed mood. This is widely tolerated as a treatment for prostate cancer, however further research is needed before it can be widely used as a strategy.

Overall, pharmacological management of paedophilia could be highly effective through reducing individuals’ sexual drive. It may work best as one part of a holistic treatment plan involving psychological support and reduced access to online sexual abuse material. It could be utilised in both primary prevention (men who have not been convicted of crimes) and secondary prevention (as part of sentencing for men who have been convicted of crimes against children). Whether this can be scaled up across Europe and North America in a cost-effective manner is unknown.

3.2. Psychological treatment

There is a lack of evidence for psychological treatment to reduce offending.[38] One meta-analysis concluded that available evidence cannot establish effect of any psychological treatment on sexual offences against children.[39] Despite many studies being conducted, only a small number met minimum standards and fewer provided useable data.

Development and evaluation of psychological treatments would benefit from further research. In other conditions, psychological therapy can be delivered online without a reduction in efficacy – this could be particularly helpful for online sexual offenders.

3.3. Pilot projects

The Dunkelfeld Prevention Project[37] was launched in Germany in 2005 and now has ten centres. These provide support for men who are sexually attracted to children but are not in contact with law enforcement. It was initially funded by the Volkswagen Foundation and latterly by the German government. It utilises pharmacological and psychological approaches to reduce offending.

In its first ten years, it had over 2000 enquiries, with 935 men completing a baseline assessment. This pilot suggests that men are willing to undergo treatment, outside the criminal justice system. Of some concern, 90% of participants continued to access child sexual abuse imagery and 20% reported further child sexual abuse offences. There is conflicting evidence as to whether the project managed to reduce risk factors associated with offending.[40]

Prevent It is a Swedish based pilot intervention of anonymous online therapy for men who wish to stop using online child sexual abuse material. It has completed an initial study, with results awaited.

3.4. Law enforcement

There is already international collaboration of law enforcement against child sex offenders, such as Interpol, an international police organisation with 192 member countries. It has a Crimes Against Children Unity which primarily focusses on sexual abuse and exploitation. It administers the International Child Sexual Exploitation police database which is used for victim identification. Interpol strongly recommended improved cooperation between countries. At present, enforcement against this online activity is overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material. Lack of resources has led to an ability to identify child victims recorded in online abuse material.

3.5. Lobbying against child marriage

Campaigning for a global age marriage of 18 could significantly reduce the risk of childhood sexual abuse for girls, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. It may also result in a wider cultural shift away from child marriage. This could be a potentially low cost, high gain intervention to reduce the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse. A reduction in the number of girls undergoing child marriage is one indication that campaigns by organisations such as UNICEF are succeeding with this strategy.

3.6. Reducing online distribution of child abuse imagery

Hash values which act as ‘digital fingerprints’ have traditionally been used to identify child sexual abuse imagery online, matching new images with a database of known illegal material. However, hash values can be easily altered by making small changes to the image. An emerging tool is PhotoDNA developed by Microsoft which matches images to known databases of illegal material, even if the original image has been altered.

The rise in videos and streaming of child abuse represents further challenges for online detection by law enforcement. This requires ongoing technological solutions in response, which requires an increased emphasis from tech companies.

Open Philanthropy is well placed to start a dialogue on the limits of online privacy and the balance that must be struck to reduce the production and distribution of sexual abuse imagery.

3.7. Building an academic field

There are few academics or clinicians dedicated to the prevention childhood sexual abuse. If novel interventions are to be delivered, credibility and prestige needs to be given to those willing to dedicate their career to this problem.

Open Philanthropy may consider funding each part of this pipeline: funding early career researchers to investigate interventions to reduce childhood sexual abuse, funding conferences for networking and sharing information, funding professorships for more established academics.

4. Neglectedness

Preventing child sexual abuse has historically been neglected, mainly relying on small charities and governmental initiatives. World Childhood Foundation, a Swedish based charity has contributed $60 million to 600 projects since its inception in 1999.[41] 50% of projects contribute to child supportive environment and relationships, 20% contribute to child online safety, 30% contribute to child focussed response to abuse.

International organisations such as the WHO and UNICEF have campaigns to reduce global violence against women and girls. UNICEF has a campaign against child marriage, which appears to be making progress.

The Oak Foundation has recently developed a programme to prevent child sexual abuse and exploitation.[42] This is the most equivalent funder (in terms of philosophy and scale) to Open Philanthropy in this space. They have programme of grants focussed on lobbying tech companies, building a global consensus to reduce child abuse, and evaluating preventative interventions.

They have been building this programme since 2018 and last year awarded $51.9 million to projects (average of $600,000) to prevent child abuse. They aim to rigorously evaluate programmes at are most effective at preventing the perpetration of child sexual abuse and ensuring these programmes can be scaled up effectively. Their grants are similar to the tractability suggestions I have outlined above.[43]

5. Potential risks and downsides

Childhood sexual abuse is a controversial topic which poses some degree of reputational risk to Open Philanthropy. There are good reasons for paedophilia to be so socially stigmatised; by bringing the topic to wider attention there is a risk of legitimising it as a sexual preference. Any move to normalise sexual attraction to children could reduce its taboo. While treating these men with compassion will face opposition from some quarters. Any move to support paedophiles through groups or online communities’ risks being compromised for nefarious purposes. Improving online detection of abuse imagery (for example by lobbying Facebook to avoid encryption of its Messenger system) may result in a backlash from online privacy advocates.

6. Major sources of uncertainty

The biggest source of uncertainty in this submission is whether interventions can reduce the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse enough to meet Open Philanthropy’s high funding bar. I believe this could be resolved by those with more expertise in health economics, but it may also require further effectiveness research into the interventions.

Although there is only a small number of trials to pharmacologically reduce the risk of childhood sexual abuse, I believe the mode of action in reducing testosterone is a robust way to suppress sex drive. I am most uncertain about how many men who are sexually attracted to children would be willing to engage with this treatment and whether this could reduce the overall prevalence of childhood sexual abuse at a population or worldwide level.

While not backed by an evidence base, there is face value in coordinating a world response to childhood sexual abuse through increased funding of law enforcement, tackling the online consumption of child abuse imagery and campaigning against child marriage.

My own expertise is as a psychiatrist; I am aware of the psychological impact of abuse in childhood and how this can have longstanding consequence in how a person relates to the world. I have no expertise in health economics, so may have largely taken the costs of childhood sexual abuse from the literature. I have little understanding of the online mechanisms to detect child sex imagery or the online subcultures relating to this material. I have largely taken this information from the investigative reporting of Gabriel Dance at the New York Times, who spoke with various experts in tech, law enforcement and survivors. His main investigation took place in 2019-2020, so the information contained in my submission could well be out of date.

Similarly, I have no experience in lobbying, campaigning pr philanthropy. I suspect consulting with experts in each of these areas could strengthen this submission. To illustrate this further, I only became aware of Oak Foundation’s drive to prevent childhood sexual abuse at the later stages of developing this submission.

7. Questions that have not been addressed in this submission

- Can youths (under the age of 18) attracted to younger children be targeted with preventative measures to avoid child abuse?

- Are there novel technological solutions to scan and detect abuse imagery? Are there solutions to online streaming of abuse?

- Does engaging men who are sexually attracted to children in treatment result in reduced consumption of child sexual abuse imagery and reduced contact childhood abuse?

- Does reducing the distribution and consumption of online abuse imagery reduce offline contact abuse?

Some experts in this area that may provide further information on the practicalities in engaging men in preventative interventions:

- Dr Christoffer Rahm, Psychiatrist at the Karolinska, leader of the Prevent It pilot

- Dr Michael Seto, Psychiatrist at the University of Ottowa, leading authority on paedophilia

- Dr Elizabeth Letourneau, Clinical Psychological and Director of the Moore Centre for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse at Johns Hopkins

8. Conclusion

Based on Open Philanthropy’s high bar for cost effectiveness, I am not convinced that reducing the global prevalence of childhood sexual abuse should immediately be a focus area. But it is an issue that negatively impacts a proportion of children worldwide, with long-term negative consequences. It is to the detriment of all society that we largely ignore the abuse many children go through and let this go undetected in the privacy of the online ecosystem.

I believe this problem is tractable and have offered potential interventions, which are likely to work best as part of a global, coordinated effort. I have uncertainty around which of these solutions are likely to be most cost effective and implementable.

Finally, this problem has historically been neglected by major funders, academia, and clinicians. Change may now be afoot, with a major grant programme being launched by the Oak Foundation. Open Philanthropy would have to ensure it can add unique value before committing to this cause area.

9. References

- ^

UNICEF. Hidden in plain sight. A statistical analysis of violence against children. 2014. https://www.unicef.org/reports/hidden-plain-sight

- ^

Qu X, Shen X, Xia R, et al. Child Abuse & Neglect The prevalence of sexual violence against female children : A systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022; 131: 1–9.

- ^

Zhang S, Lin X, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of childhood trauma measured by the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in people with substance use disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020; 294: 113524.

- ^

Stoltenborgh M, van IJzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat 2011; 16: 79–101.

- ^

Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T. The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2013; 58: 469–83.

- ^

UNICEF. Child Marriage. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/

- ^

Keller MH, Dance GJX. Child abusers run rampant as tech companies look the other way. New York Times 2019; : 1–8.

- ^

Dance GJX, York N, Online T, York N, York N. Facebook Encryption Eyed in Fight Against Online Child Sex Abuse. 2019; : 2–5.

- ^

Milmo D. Campaign aims to stop Facebook encryption plans over child abuse fears. Guard 2022; : 1–5

- ^

Seto MC, Buckman C, Dwyer RG, Quayle E, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Production and Active Trading of Child Sexual Exploitation Images Depicting Identified Victims. 2018. https://www.missingkids.org/content/dam/pdfs/ncmec-analysis/Production and Active Trading of CSAM_FullReport_FINAL.pdf

- ^

Interpol, ECPAT International. Towards a global indicator on unidentified victims in child sexual exploitation material. 2018. https://ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/TOWARDS-A-GLOBAL-INDICATOR-ON-UNIDENTIFIED-VICTIMS-IN-CHILD-SEXUAL-EXPLOITATION-MATERIAL-Summary-Report.pdf

- ^

Hailes HP, Yu R, Danese A, Fazel S. Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 830–9.

- ^

Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abus Negl 2012; 36: 156–65.

- ^

Fang X, Fry DA, Brown DS, et al. The burden of child maltreatment in the East Asia and Pacific region. Child Abus Negl 2015; 42: 146–62.

- ^

Letourneau EJ, Brown DS, Fang X, Hassan A, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child sexual abuse in the United States. Child Abus Negl 2018; 79: 413–22.

- ^

UK Home Office. The economic and social cost of contact child sexual abuse. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-economic-and-social-cost-of-contact-child-sexual-abuse

- ^

Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1223–49.

- ^

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Ramos Rodriguez G, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Heal 2019; 4: e517–28.

- ^

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Diagnostic Classification. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2013.

- ^

Seto MC. Pedophilia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009; 5: 391–407.

- ^

Love S. Pedophilia Is a Mental Health Issue. It’s Still Not Treated as One. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/y3zk55/pedophilia-is-a-mental-health-issue-its-still-not-treated-as-one

- ^

Savoie V, Quayle E, Flynn E. Prevalence and correlates of individuals with sexual interest in children: A systematic review. Child Abus Negl 2021; 115: 105005.

- ^

Landgren V, Savard J, Dhejne C, et al. Pharmacological Treatment for Pedophilic Disorder and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder: A Review. Drugs 2022; 82: 663–81.

- ^

Landgren V, Malki K, Bottai M, Arver S, Rahm C. Effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist on risk of committing child sexual abuse in men with pedophilic disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2020; 77: 897–905.

- ^

Schober JM, Kuhn PJ, Kovacs PG, Earle JH, Byrne PM, Fries RA. Leuprolide acetate suppresses pedophilic urges and arousability. Arch Sex Behav 2005; 34: 691–705.

- ^

Wincze JP, Bansal S, Malamud M. Effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate on subjective arousal, arousal to erotic stimulation, and nocturnal penile tumescence in male sex offenders. Arch Sex Behav 1986; 15: 293–305.

- ^

McConaghy N, Blaszczynski A, Kidson W. Treatment of sex offenders with imaginal desensitization and/or medroxyprogesterone. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 77: 199–206.

- ^

Hucker S, Langevin R, Bain J. A double blind trial of sex drive reducing medication in pedophiles. Ann Sex Res 1988; 1:227-242.

- ^

Cooper AJ, Sandhu S, Losztyn S, Cernovsky Z. A double-blind placebo controlled trial of medroxyprogesterone acetate and cyproterone acetate with seven pedophiles. Can J Psychiatry 1992; 37: 687–93.

- ^

Cooper AJ. A placebo-controlled trial of the antiandrogen cyproterone acetate in deviant hypersexuality. Compr Psychiatry 1981; 22: 458–65.

- ^

Bradford JMW, Pawlak A. Double-blind placebo crossover study of cyproterone acetate in the treatment of the paraphilias. Arch Sex Behav 1993; 22: 383–402.

- ^

Bancroft JHJ. The control of deviant sexual behaviour by drugs. J Int Med Res 1975; 3: 20–1.

- ^

Finkelstein JS, O’Dea LSTL, Whitcomb RW, Crowley JR. Sex Steroid Control of Gonadotropin Secretion in the Human Male. II. Effects of Estradiol Administration in Normal and Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone-Deficient Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991; 73: 621–8.

- ^

Wainberg ML, Muench F, Morgenstern J, et al. A double-blind study of citalopram versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive sexual behaviors in gay and bisexual men. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67: 1968–73.

- ^

Tennent G, Bancroft J, Cass J. The control of deviant sexual behavior by drugs: A double-blind controlled study of benperidol, chlorpromazine, and placebo. Arch Sex Behav 1974; 3: 261–71.

- ^

Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 2021; 42: 354–73.

- ^

Beier KM, Grundmann D, Kuhle LF, Scherner G, Konrad A, Amelung T. The German Dunkelfeld Project: A Pilot Study to Prevent Child Sexual Abuse and the Use of Child Abusive Images. J Sex Med 2015; 12: 529–42.

- ^

Långström N, Enebrink P, Laurén EM, Lindblom J, Werkö S, Karl Hanson R. Preventing sexual abusers of children from reoffending: Systematic review of medical and psychological interventions. BMJ 2013; 347: 1–11.

- ^

Grønnerød C, Grønnerød JS, Grøndahl P. Psychological Treatment of Sexual Offenders Against Children: A Meta-Analytic Review of Treatment Outcome Studies. Trauma, Violence, Abus 2015; 16: 280–90.

- ^

Mokros A, Banse R. The “Dunkelfeld“ Project for Self-Identified Pedophiles: A Reappraisal of its Effectiveness. J Sex Med 2019; 16: 609–13.

- ^

World Childhood Foundation. 2022. https://childhood.org/

- ^

Oak Foundation. 2022. https://oakfnd.org/

- ^

Oak Foundation Grant Database. 2022. https://oakfnd.org/grants/