[I am a career advisor at 80,000 Hours writing in a personal capacity here. I've been thinking about something Will MacAskill said recently in an interview with my shrimp-friend Matt: "should people be more ambitious? I genuinely think yes. I think people systematically aren't ambitious enough, so the answer is almost always yes. Again, the ambition you have should match the scale of the problems that we're facing—and the scale of those problems is very large indeed."

This post is my reflection on these ideas.]

************

My last post argued that if you want to have a great career, your goal should not be to get a job. Instead, you should choose an important problem to work on, then “get good and be known.” Building skills will allow you to solve problems and reap the benefits.

In the ~500 career advising calls I’ve hosted in the past year, the most common response I’ve heard has been: “Okay, how good? How well known? How many hours of practice will get me there?” Most people want to calibrate their ambitions so that the time and energy they invest feels worth it to them.

I empathize with this, but when I’m honest– with myself for my own goals, with the people I see working on important problems full time, and with so many who are trying to break into meaningful careers– I’m desperate for altruistic people to be more ambitious. I wish more people realized that:

- There is a massive gap between the average person’s level of ambition and those of top performers. Until you’ve seen it up close or read a few biographies, it’s hard to realize the pathological urge some people feel to improve their skills, to set absurd goals, and to do what’s necessary to achieve them.

- Despite this, most extremely ambitious people are focused on unimportant problems. For whatever reason, workaholic strivers are usually more interested in seeking status or power than in solving real problems to reduce suffering and keep people safe.

- Because your ambitions should ideally match the scale of the problem that you’re trying to solve, if you genuinely care about improving the world, you should aim much higher and work much harder than the average person. Conversely, if the problem you’re trying to solve in life is to maximize KPIs for Deloitte, who the hell cares. Rise to whatever occasion you’ve set for yourself.

It’s hard to figure out how to become more ambitious, but I think it’s possible. Ambition seems to be quite malleable. You can read great biographies, surround yourself with other ambitious people, set up systems to remind yourself what you’re working for and why, set concrete goals, work in public, etc. Regardless, I think the first step is to realize that your ambition is a lever you can pull at all.

It’s far too easy to coast on established routines and comfortable positions. If I let myself, my ideal day would probably involve hours of playing Factorio, laughing with my wife, chatting with friends, then maybe sending 2 emails. By default, all of us are pulled down by the gravity well of a “good enough” career. If we lived in a saner world, I probably wouldn’t care much about my career– I’d be happy to enjoy life and get by.

But my god, there is work to do. Millions of people will die of preventable diseases this year. Billions of animals will be tortured in factory farms. Catastrophic risks like nuclear war and pandemics are still with us, and we might be on the cusp of a misaligned AI intelligence explosion. The world is full of horrific problems at a pretty fragile moment in our history. As I look around at people who have realized this intellectually, I’m desperate for us to aim higher and work harder.

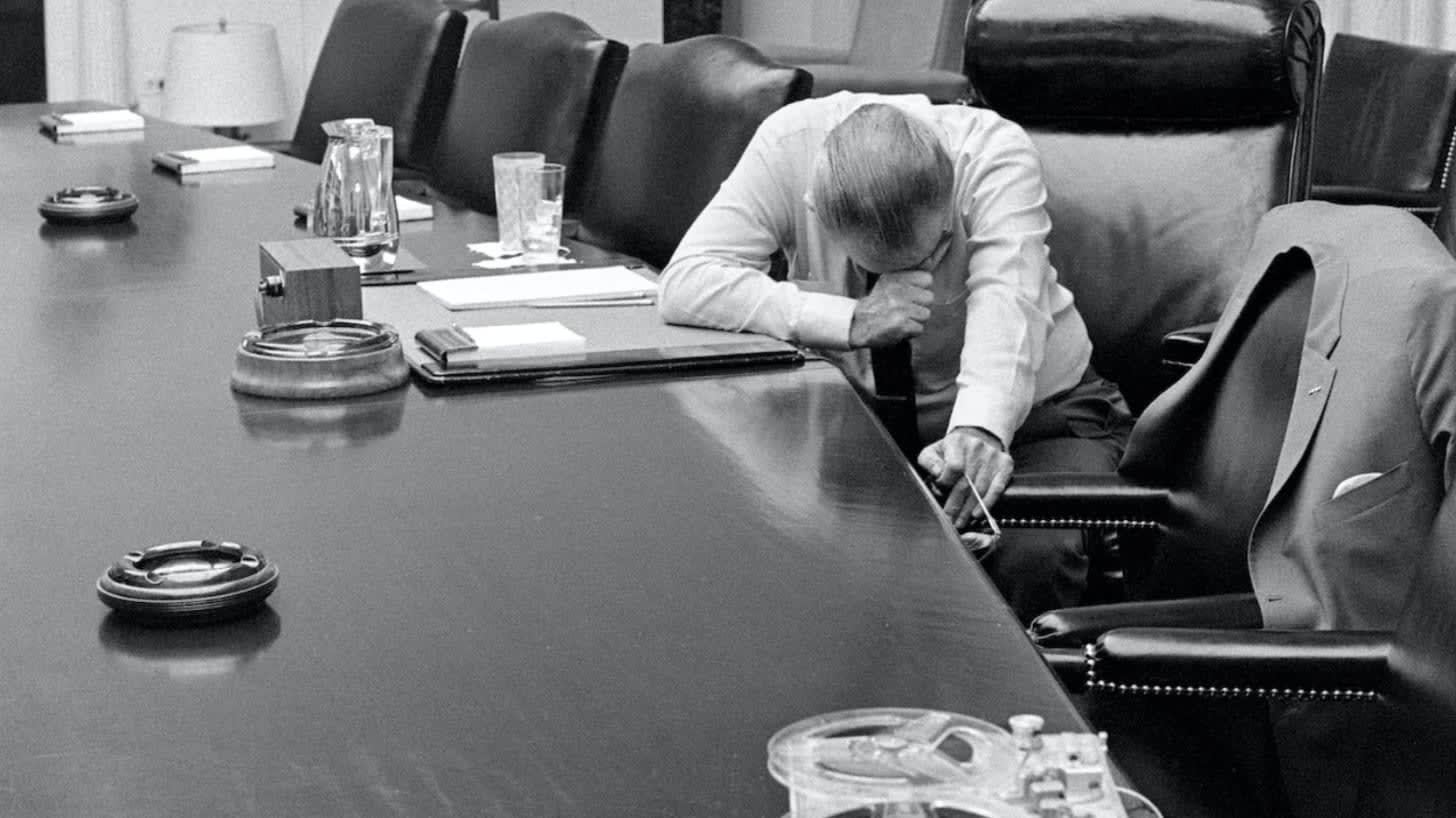

When I think of the scale of suffering and risk in the world today, yet get stuck on the couch scrolling on my phone instead of working, I try to remember this passage about Lyndon B Johnson from Robert Caro’s Means of Ascent:

“I never knew a man could work that hard”; at every stage in his adult life—as Congressman’s secretary, Congressman, senatorial candidate—he had displayed a willingness to push to their very edge, and beyond the edge, the limits not only of politics but of himself.

In every crisis in his life, he had worked until the weight dropped off his body and his eyes sunk into his head and his face grew gaunt and cavernous and he trembled with fatigue and the rashes on his hands grew raw and angry, and whenever, at the end of one more in a very long line of very long days, he realized that there was still one more task that should be done, he would turn without a word hinting at fatigue to do it, to do it perfectly. His career had been a story of manipulation, deceit, and ruthlessness, but it had also been a story of an intense physical and spiritual striving that was utterly unsparing; he would sacrifice himself to his ambition as ruthlessly as he sacrificed others. If you did “everything, you’ll win.” To Lyndon Johnson, “everything” meant literally that: absolutely anything that was necessary. If some particular effort might help, that effort would be made, no matter how difficult making it might be.

Dwarkesh notes that this extremely ambitious “willingness to do everything” is usually correlated with other goals like an “unyielding need for personal power, wealth, or status.” The passage above is rarely the profile of a nonprofit do-gooder, or even a truth-seeking academic, but I’d love for those working outside of traditionally ruthless environments to learn to emulate some of it.

In the rest of this post I’ll share examples of other top performers whose efforts have inspired me, from Jensen Huang to Jiro Ono, sharing aspects of their craftsman mentality that I’ve tried to emulate even 1% of. Then, I’ll argue that most extreme ambition is misplaced, spent on seeking hollow status or wealth. Against this, I’ll share strategies for how people who care about helping the world can try to raise the level of their ambitions to match their worldview. Lastly, like any good Substack, I’ll tie this all back to AI, asking what ambition means at the end of the human era.

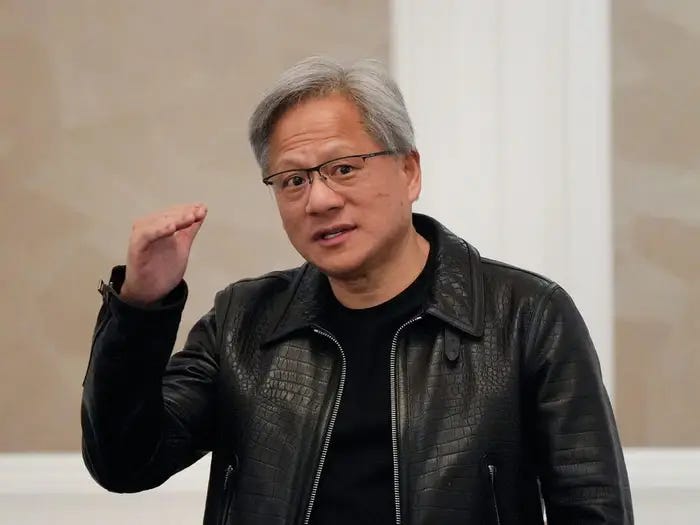

Jensen Huang is more ambitious than you

I enjoyed The Thinking Machine, Stephen Witt’s biography of Jensen Huang. It describes a ferociously ambitious founder who was hungry to work late, read every book, set extreme goals, shout when necessary, and grit through painful levels of risk tolerance. His success was not guaranteed; Nvidia almost failed three times. In 1996, Sega invested $5 million into Nvidia just weeks before they would have been unable to pay their employees. Jensen claims that this $5 million investment would be worth about $1 trillion today (though due to dilution, the real number is probably closer to $150 billion– Jensen tends to exaggerate).

As a child, Jensen was a bullied immigrant with something to prove in America. In his early teens he started doing 100 pushups a day and has never stopped. In high school, as a competitive table tennis player he “outworked everyone,” spending an entire summer doing nothing but practicing. In his first technology jobs, Huang found collaborators who “shared a readiness to sacrifice their personal lives and their sanity” to solve technical problems. His eventual cofounder remarked that back then, “there was no notion of weekends,” only days that started at 7:00am and ended with calls from their girlfriends to please come home at 9:00pm.

When he worked at the LSI Logic Corporation, Huang built a new division from the ground up to reach $250 million in annual revenue. He leveraged bets on specific technological innovations like abstractions in chip design, tracking down experts who had written textbooks on graphics accelerators and not relenting until they’d speak with him. When a senior director from Intel was hired to co-manage his team at LSI, Huang felt slighted and quit. His peers said that “He wanted to run something by the age of 30.” In January 1993, just a few months before Jensen’s 30th birthday, Nvidia was incorporated.

There is a lot from The Thinking Machine that can’t be replicated, like leveraging bets on parallelization and GPU emulation that were correctly timed for the industry. 35 other startups were competing with Nvidia before it was even founded, and luck obviously played a role. Still, when I read the book I felt motivated. I saw that it’s possible to want more, to work that extra hour and read that extra book, and to achieve goals that seemed insane at first. Working hard alone is not sufficient, but when you read about someone like Jensen, you realize you’ve basically never worked hard.

There’s also a lot in The Thinking Machine that probably shouldn’t be emulated, like berating employees for hours. I’m not suggesting that anyone working at a do-gooder nonprofit could or should decide to become a Jensen-type figure tomorrow. But at the margin we probably need more of this energy, not less.

In Latin, invidia means “envy.” I hope that the level of ambition required to reach “CEO of a ~$4.5 trillion market cap company” does not require an envious pathology. Yet other Nvidia co-founders like Curtis Priem cashed out much earlier, being happy to become merely rich. Priem moved to a $6 million ranch and is on track to donate half a billion dollars by the end of his life. If he had held his shares they would be worth almost $100 billion today, but Priem says he doesn’t regret it. It would have been too risky, too volatile.

Priem seems like the more rational person to me. Jensen’s ambitions are in service of driving shareholder value for Nvidia, or charitably they’re to push the human technological frontier– but at the personal level, it takes a special kind of person to be dissatisfied with merely being a multi-billionaire. At another moment in the book, Huang botches a dinner he was cooking in his million-dollar kitchen. He “exploded and began to scream at his inadequate equipment. ‘I think we all understood we had to get out of the kitchen [...] It was just time for Jensen to yell at his stove.” I don’t think Huang’s final pursuits are worthy of his pathological level of ambition.

At the end of the book, Jensen berates his biographer for asking too many questions about AI safety. In Stephen Witt’s final interview with him, Jensen unleashed “twenty minutes” of “uncontained, omni-directional, and wildly inappropriate” shouting. The anger was sparked when Witt showed him a 1964 Arthur C. Clarke video predicting future AI systems that will “out-think their makers.” Witt asked whether humanity was prepared for the potential risks that could arrive in such a world. Jensen was not happy:

“This cannot be a ridiculous sci-fi story,” he said. He gestured to his frozen PR reps at the end of the table. “Do you guys understand? I didn’t grow up on a bunch of sci-fi stories, and this is not a sci-fi movie. These are serious people doing serious work!” he said. “This is not a freaking joke! This is not a repeat of Arthur C. Clarke. I didn’t read his fucking books. I don’t care about those books! It’s not– we’re not a sci-fi repeat! This company is not a manifestation of Star Trek! We are not doing those things! We are serious people, doing serious work. And – it’s just a serious company, and I’m a serious person, just doing serious work.”

People working toward altruistic ends are often trying to overcome market failures or policy failures. There’s some problem in the world that our institutions are not solving by default, so we need do-gooders to make personal sacrifices and try to remedy them. To be effective at this, I think we have to realize what ferocity comes out the other end of market pressures and political competition. We will never be Jensen, but we are swimming upstream against him.

“I don’t know how to do it, but for all of you Stanford students, I wish upon you ample doses of pain and suffering. Greatness comes from character and character isn’t formed out of smart people — it’s formed out of people who suffered.”

- Jensen Huang 😅

Most extreme ambition is misplaced

Jiro Ono, a sushi chef with three Michelin Stars, from Jiro Dreams of Sushi.

A necessary condition for greatness is the desire to achieve it. Career advice is full of truisms like this, but I hope the previous section showed how intense the desire for greatness can really be. Few of us ever experience it anywhere near the degree of top performers.

But in any of this, it’s just as important to ask: “greatness at what?” The greatest plant scientist developed disease-resistant wheat varieties that are credited with saving over a billion lives from famine. The greatest competitive eater ate eighty three hot dogs in ten minutes (with a genuinely impressive work ethic and mentality applied to unworthy goals). I think the former is much more important, but most ambitious people look more like the latter.

For example, I think Jiro Dreams of Sushi is a sad story. I don’t mean to be an asshole to a 100 year old man who still works on creating world-class meals to make people happy– I admire his craftsmanship and found it personally inspiring for other skills. But if I was to list a thousand problems that are worth burning a lifetime of effort on, improving the marginal bite of luxury sushi would not come close to making the list. Jiro sacrificed everything for this. His son describes how he was essentially absent from their childhood, leaving for work before they woke and returning after they were asleep. Jiro told his sons they’d be better off on the streets than coming home if they ever quit apprenticing.

The documentary tries to wring a hopeful story out of its protagonist: his own terrible childhood on the streets at nine years old where he developed a work ethic to survive; his rise to success through painstaking detailed effort; his decades of single-minded devotion finally earning him three Michelin stars and the title of the world’s greatest sushi chef. But watching, I couldn’t help but despair at whether this was all worth it.

I don’t know whether Jiro could have used his career to help the poor or work on any of a thousand more pressing problems directly– maybe there is no counterfactual here. Japanese philanthropic culture tends to be more private so I can’t say for certain, but I also don’t see anything about Jiro using his fame or wealth to contribute to those who are suffering in poverty like he did when he was a child…

Other than a few exceptions (Fred Hollows, who enabled millions of cataract surgeries across the developing world, or Viktor Zhdanov, who drove the WHO smallpox eradication campaign), there are rarely stories of altruistic do-gooders with Jiro’s work ethic. And when they do exist, they are much less famous, leading to fewer memes to shape young people’s own ambitions.

Robert Caro’s LBJ biographies showcase this dynamic again and again. As Dwarkesh writes in his review of Caro, society at its best tries to align these peoples’ self-interest with the social good rather than suppressing it altogether. LBJ eventually did incredibly important work on civil rights and liberalism, but his ambition was pathological even decades beforehand:

“In college, Johnson was blackballed by an exclusive club called the Black Stars. So he formed the White Stars, and from it, he practiced the same Machiavellian talents which he would eventually rehearse on the national stage. He would steal elections, distribute to loyal friends the patronage he earned from kissing up to administrators, and even direct members to sleep with girls in order to manipulate their votes. Who would bother doing all this to win a college election? The kind of person who could eventually win a national election.”

We see this dynamic all the time in fiction about extremely ambitious people as well. Everyone knows Captain Ahab is insane, but frankly so is his crew, and most people seeking glory and adventure. Matt Yglesias writes:

“[Ahab] is driven mad by his rage and is counterpoised to the rational first mate, Starbuck, who wants to focus on the actual job at hand rather than risk everyone’s lives on a quest for revenge. But the gruesome and lengthy description of how sperm whales are normally tracked and hunted and butchered makes it clear that there’s something kind of insane about Starbuck’s quest, too. You’re on a years-long ocean voyage across the entire world (because the North Atlantic whale population has already been depleted) in miserable conditions, engaged in grotesque and brutal butchery, all so that people can have nicer candles.”

All I hope is that some people at the margin who care about bigger problems will pick up a tenth of this spirit and channel it for good.

Okay, how can altruistic people aim higher and work harder?

I think the first step toward raising your own ambitions is to realize that it’s a lever that exists to be pulled at all. Reading about top performers can help, but meeting them is even better. It’s incredible to work with someone who seems to pull from a deep well of energy and who is constantly working on improving themselves. That’s partly why my last post encouraged networking, tightening your feedback loops, and working in public to find these people and help them find you.

Beyond that, I think it’s worth testing a range of approaches:

- Protect your attention: carve out deliberate space to work on projects. This might be a physical room (i.e. going into an office without your phone or distractions), it might be an inflexible 4 hour chunk of time each Saturday, etc.

- Like Jensen, Paul Graham has argued that determination requires some pain. You do have to be at least somewhat hard on yourself to offset the costs of cultivating discipline. But this compounds over time, so consistency is more important than severity.

- Build strong network effects: the city you live in and your social groups will shape your ambitions. Ambitious people should try to meet others like them in person. Could you move? Go to a new event?

- If you’re reading this, maybe you’ve just never been put in the right context: “Probably most ambitious people are starved for the sort of encouragement they’d get from ambitious peers, whatever their age.” I personally grew up in a small town and didn’t hit my stride until I met other people who were hungry.

- You should state your goals clearly and directly, rather than letting them sit unspoken in the background. Quarterly journaling can help with this, but whatever goal tracking system you use, you should have something.

- Tyler Cowen has said that one of the cheapest valuable things we can do is to raise the ambitions of others– showing them that they might be able to accomplish more than they realized, and faster. I’ve tried to do that in this post, but hopefully in your life you have mentors to nudge you as well. Leave a comment about your situation and I’ll try!

- Developing your own theory of change for your work can be motivating and help ensure that you’re investing time into worthwhile projects.

These are just a few incomplete answers. If you’ve read this far, I hope you let yourself experiment with a few and try some new strategies to improve your skills over time. In my own industry, I’m reminded of Stephen Witt’s description of Jensen’s early career, where he “seemed genuinely surprised that there were people in his industry who didn’t want to spend fourteen hours a day fiddling with the circuit simulator.”

I don’t work nearly fourteen hours a day, but I sometimes feel similarly about jobs dedicated to improving the lives of others. The times I’ve been able to help someone land a high-impact role that they wouldn’t have otherwise been so rewarding to me. I’ll get off a call with someone who thanks me for introducing them to the person who hired them and wonder, why am I doing anything else? Why don’t I take more advising calls, work more hours, meet more people, even if it means just one extra person can change their life trajectory? Incorporating feedback loops like this into your work can be one way to keep the ambition flywheel going.

Ambition at the End of the Human Era

I get most frustrated by this altruistic ambition gap for problems related to AI. I move in social circles that have been closely following the pace of AI progress for many years. I know people who have come to believe that humanity might be on the cusp of inventing Artificial General Intelligence– AI systems that can perform any intellectual task that a human can, roughly as well as an economically productive human, including AI research itself.

Some in these circles believe that there is a non-trivial chance of catastrophic, world-changing events taking place from the development of AGI within the next five to ten years. If you count yourself as someone working to improve the trajectory of AI’s development, you know what I’m describing. I recognize a range of difficult questions within this perspective– competing threat models, theories of change, timelines for progress, distributions of good and bad outcomes, and other uncertainties. This stuff is hard!

The easy question, I think, is how the change should find us.

In 1948 CS Lewis said “Let that bomb, when it comes, find us doing sensible and human things – praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, [etc…]” This ethos is sensible for most people (who are unable to contribute to solving these problems), but it is an unacceptable answer for those working on AI today. If you wake up every morning and try to improve the trajectory of the transformative AI systems that could remake the world, you have an obligation. What percentage of humanity gets to influence these decisions, even at the margin?

When the future finds us, it should see us fighting like hell.

We should work hard in these pivotal years, leaving nothing on the table. Some believe that the entire nature of work could be radically transformed soon… How are we using these last years being information processing agents who move bits around a screen? Some believe there is a non-trivial chance that many people on earth could die through misuse or irresponsible development… Could we tell those people that we did all that we could with the time we had?

I want people working on big problems to be hungry. To shake complacency. To not get caught up in the short term incentives in their day to day work (or lack thereof). When I don’t prepare enough for an advising call with someone, or I read a Twitter summary instead of reading the paper everyone is talking about, or I faff around for a day at the office, I feel I am abdicating the future. I hope our ambitions rise to meet these last years of the human era.

Closing Caveats - Efficiency, Burnout, and Choosing What Matters

Of course in all of this, I want your impact and career trajectory to be sustainable. I’ve written before about how burnout is real and it is horrible. 60 minutes a day of deliberate practice over a year will compound far more than a couple weekends of crazed effort. You should get lots of feedback to ensure you’re growing in the right direction, as choosing what to aim at is often more important than running fast. You should fold “learn and grow strategically, not just fast” into your ambitions.

I should also note that some subset of people might need to hear the opposite advice, as is sometimes the case in career advising. It can be valuable to speak with peers or mentors about how well calibrated your level of ambition is, especially to ensure you’re aiming at the right things and using the right strategies to get there.

My last post also described some ways to make your deliberate practice efficient– finding the 20% of effort that leads to 80% of results. For most people this will be the best approach to start working on a new problem, myself included. Outliers like LBJ or Jensen will always be out there, stretching to hit 100%, powered by a white-hot star of ambition that’s hard to imagine. We might not get there ourselves, but it can be inspiring to read about them and realize what is possible.

That said, for every one Jensen there are a thousand failed founders who fried their marriage and wasted their most productive years for nothing; children who missed time with their parents, moments that can never come back. You should be clear-eyed about what you’re getting into and decide to what degree the problems you see in the world are worth your ambitions.

But once you’ve set your sights on something, you should get good, be known, and work hard. If your cause is worth fighting for, you should fight like hell. How ambitious are you? What do you allow yourself to yearn for?

-----

This post is written in my personal capacity and reflects my views, not those of my employer. However, if you find these arguments compelling, you might be interested in 80,000 Hours, or other organizations like ProbablyGood.