Summary

For my MLSS project, I created this distillation of “Is power-seeking AI an existential risk?” which was originally written in 2021 by Joe Carlsmith, an analyst at Open Philanthropy. After a while, Stephen McAleese contacted me and proposed to re-edit it and upload it as a post. Here is the result.

The report estimates the level of existential risk from AI by breaking the possibility of an existential catastrophe from AI down into several enabling steps, assigning probabilities to each one, and estimating the total probability by multiplying the probabilities. The report concludes that advanced AI is a potential source of existential risk to humanity and has a roughly 5% chance of causing an existential catastrophe by 2070. A year later Carlsmith increased his estimate to >10%.

Introduction

The report is about risks from advanced artificial intelligence by the year 2070. The year was chosen by the author because it’s near enough to be within the lifetimes of people alive today while being far enough to reason about the long-term future. Carlsmith reasons that highly intelligent reasoning and planning agents will have an instrumental incentive to acquire and maintain power by default because power increases the probability of agents achieving their goals for a wide range of goals. Power-seeking in AI systems would make them particularly dangerous. Unlike passive risks such as nuclear waste, since power-seeking AI systems would actively search for ways to acquire power or cause harm, they could be much more dangerous.

Therefore, the existential risk posed by advanced AI systems could be relatively high. Risk can be decomposed such that Risk ≈ (Vulnerability x Exposure x Severity) / Ability to Cope. Advanced AI seems like a risk that would have high severity and exposure and possibly high overall risk. The general background of the report includes two important points: (a) intelligent agency is an extremely powerful force for controlling and transforming the world, and (b) building agents much more intelligent than humans is “playing with fire”. In the following sections, I’ll describe the six events mentioned in the report that would need to happen for AI to cause an existential catastrophe and estimate the probability of each one to calculate an overall estimate of existential risk from AI by the year 2070. Note that whenever I am describing a particular hypothesis and probability, it is conditional on the assumption that all previous hypotheses are true.

Claims

The report makes high-level claims or hypotheses about future AI systems and assigns probabilities to them to get an overall estimate of the level of future AI risk.

[1]: It will become possible and financially feasible to build AI systems with three main properties: Advanced capabilities, Agentic planning, and Strategic awareness. (Call these “APS”—Advanced, Planning, Strategic—systems.)

My estimate is 75%. This possibility seems to be the one least described in the paper though, and therefore my estimate comes from my own subjective forecast of the trajectory of AI progress.

Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments (Legg, 2007). Intelligence can be divided into two parts (a) learning and using a model of the world that represents causal relationships between actions and outcomes (epistemic rationality) and (b) selecting actions that lead to outcomes that score highly according to some objective (instrumental rationality).

Many physically possible forms of AI systems could be much better at doing this than humans, and given the tremendous progress that has been made on AI recently, it seems likely that we will create super-human AI systems at some point in this century.

Human cognition is constrained by several biological constraints such as cell count, energy, communication speed, signaling frequency, memory capacity, component reliability, and input/output bandwidth. The fact that AI systems need not have any of these constraints is an argument in favor of the possibility that AI systems will surpass human intelligence someday. Conversely, it could be true that general intelligence is very hard to replicate. Though recent advances in AI generality seem to be evidence against this possibility.

[2]: There will be strong incentives to build and deploy APS systems | (1).

My estimate is 90%. The main reason for this estimate is the immense usefulness of APS systems. Advanced capabilities are already useful in today's applications, and it’s likely that they will be increasingly useful as AIs become more capable. Many tasks such as being a CEO may require a strong world model and the ability to master a wide variety of tasks. Much of the world’s economically valuable work is being done by employees with relatively high levels of autonomy (e.g. building a mobile app that does X). If many tasks are of this nature, APS-like systems might be required to automate them. Alternatively, AI systems might become more like APS systems unintentionally as they become more advanced.

My 10% estimate that this claim won’t come true, comes centrally from the unlikely possibility that the combination of agentic planning and strategic awareness won’t that useful or necessary for any task. However, even if advanced non-APS systems are sufficient to perform X tasks, APS systems could probably perform these tasks and some other additional tasks. In any case, it is relevant to mention here that we need to be cautious when predicting what degree of agentic planning and/or strategic awareness will be necessary to perform some tasks. In particular, we should avoid reasoning like “Humans do X task using Y capabilities, so AI systems that aim to do X will also need Y capabilities” or “obviously task X needs Y capabilities”.

[3]: It will be much harder to develop APS systems that would be practically PS-aligned if deployed, than to develop APS systems that would be practically PS-misaligned if deployed (even if relevant decision-makers don’t know this), but which are at least superficially attractive to deploy anyway | (1)–(2).

Definition: an AI system is PS-aligned if it is aligned for all physically compatible inputs.

My estimate for this claim is 55%. Because of the difficulty of creating accurate proxies, there is a considerable chance that we will build intelligent systems with misaligned behavior: unintended behavior that arises specifically because of problems with objectives. Because of the instrumental convergence thesis, a wide variety of agents will naturally seek power which makes corrigibility—the ability to easily modify or shutdown misbehaving agents—difficult to achieve. Misaligned agents may have an even greater incentive than aligned agents to seek power. Situationally-aware misaligned agents would realize that they need the power to overcome the resistance of other agents such as humans. Misaligned agents would also have an incentive to be deceptive which would make it difficult to identify or debug misaligned agents.

The challenge of power-seeking alignment is as follows: (1) Designers need to design APS systems such that the objectives they pursue on some set of inputs X do not give rise to misaligned power-seeking, and (2) they (and other decision-makers) need to restrict the inputs the system receives to X. Thus, the most relevant subproblems to lower the probability of this hypothesis would be:

- Controlling objectives. Is difficult because of problems with proxies: systems optimizing for imperfect proxies often behave in unintended ways and problems with search: systems may find solutions to an objective that is not desirable.

- Controlling capabilities. Note that less capable systems have stronger incentives to cooperate with humans. Capability control can be achieved via specialization: reducing the breadth of a system’s competencies, preventing problematic improvements or inputs a system receives that might result in improved capabilities, and preventing scaling. Controlling capabilities could be difficult given that there will probably be a strong incentive to increase capabilities—cognitive enhancement is an instrumental convergent goal.

There are also some additional difficulties to the challenge of power-seeking alignment such as:

- Interpretability. Safety and reliability usually require understanding a system well enough to predict its behavior. However, current state-of-the-art neural networks turn out to be so complex that we currently cannot completely understand them. Therefore, it seems reasonable to think that this could be also the case for APS systems as the complexity of APS systems could be much greater than that of current ML models.

- Adversarial dynamics. We could monitor or evaluate APS systems in order to detect problems with their objectives. However, these systems would be incentivized to deceive their operators to appear safer. A situationally aware system would realize that manipulating the beliefs of its designers increases its chances of getting deployed and optimizing its objectives.

- Stakes of error. The consequences of failing to align an APS system could be dire and since AIs will have an instrumentally convergent incentive to avoid changes to their objective function—goal-content integrity—we might only get one chance.

These factors make the overall difficulty of the problem seem high. My 45% estimate that the problem is not too difficult comes from the possibility that we could eventually solve some of these subproblems. But I’m very uncertain about this estimate.

[4]: Some deployed APS systems will be exposed to inputs where they seek power in unintended and high-impact ways | (1)–(3)

My estimate is 85%. In particular, I think we could control the circumstances of the APS systems to lower the probability of it being exposed to dangerous inputs. However, there could still be a huge number of potentially dangerous inputs and the problem of classifying which ones are malicious seems hard. Therefore it seems likely that if a misaligned-power-seeking AI is deployed it would probably end up encountering one or more malicious inputs.

However, Carlsmith also mentions that if a technology is hard to make safe, it doesn't necessarily follow that many people will use it dangerously. Instead, they might modify their usage to take into account the level of safety attained. For example, if we were unable to create reliable crash-free aircraft, we wouldn't anticipate a constant stream of fatal crashes, but rather a decline in air travel. Something similar could happen with APS systems. If we detect they could be dangerous if exposed to some given inputs, we would decrease their usage and therefore, their exposure to malicious inputs. Though this argument doesn’t apply if a single use of the system is so catastrophic that we can’t even learn to use it less.

A relevant factor here is the timing of problems, as problems before deployment are a priori preferable to those that occur after deployment. However, not all pre-deployment problems will be detected if APS systems tend to hide their intentions in order to get deployed. Also, APS systems that are aligned pre-deployment could misbehave after deployment if they are exposed to malicious inputs.

Another relevant issue is the factors influencing decisions about deployment which include decision makers' beliefs and perceived cost-benefits. Deception could influence these beliefs: an APS system would be incentivized to understand and convince its operators that it’s aligned to increase its probability of being deployed regardless of whether or not it is really aligned.

Some key risk factors that would encourage hasty deployment are externalities and competition. First-mover advantages could incentivize shortcuts on safety procedures. A greater number of actors would increase competitive dynamics. Usefulness is also relevant—systems that are more useful are more likely to be intentionally deployed.

[5]: Some of this power-seeking will scale (in aggregate) to the point of permanently disempowering ~all of humanity | (1)–(4).

My estimate is 50%. Discussions of existential risk from misaligned AI often focus on “take-off” scenarios—the transition from some lower level of frontier AI capability A to some much higher and riskier level B. When it comes to preventing these types of events, we have some tools that can help us to prevent them. One of them is warning shots which consist of experimenting with weaker systems in controlled environments to trigger tendencies towards misaligned power-seeking. However, relying on this tends to be over-optimistic for several reasons: (a) recognizing a problem does not solve it, (b) there will be fewer warning shots as capabilities increase, and (c) even with inadequate techniques, some actors could still push forward with deployment.

Competition for power among power-seeking agents (including humans) is also an important factor to consider. However, both unipolar and multipolar scenarios governed by AI systems won’t matter that much regarding risk. What matters is whether humans are disempowered or not. There would be a struggle between power-seeking agents' capabilities and the strength of the human opposition—e.g. employing corrective feedback loops—and therefore it would be relevant to know how capable APS systems would be.

There are two main types of power: hard power, the use of force to influence the behavior or interests of other actors, and soft power which is the use of cultural tools to persuade other actors. It might be relatively difficult for these APS systems to get hold of an embodiment with which to exercise a hard power. Regarding soft power, persuasion has its limits, and convincing an agent (with human intelligence level) to do something that blatantly goes against its interests could be difficult to achieve, even for an APS system.

[6]: This disempowerment will constitute an existential catastrophe | (1)–(5).

My estimate is 90%. The term catastrophe here is understood as an event that drastically reduces the value of the trajectories along which human civilization could realistically develop (Ord, 2020). If (1)–(5) happens, that would mean the disempowerment of humanity. This means that humans would take a back seat and the most relevant decisions taken on the planet would be made without considering us.

The point to consider why disempowerment could not be a catastrophe comes with the “intrinsic rightness” argument. It argues that cognitive systems will converge on similar objectives within the limits of intelligence. However, it seems that “intrinsic rightness” is a bad reason for expecting convergence. The object that differentiates us as moral agents is the fact that—apart from being intelligent—we can feel certain kinds of negative (fear, anguish) and positive (joy, enthusiasm) experiences. If these systems do not possess these qualities, we should not expect for them any kind of moral standard, and this would make it difficult to converge with human values.

If humans were surpassed in intelligence by advanced AI it would be an immense paradigm shift. A useful analogy for understanding what the world would be like afterwards is to consider the relationship humans have with other animals and observe how we “keep their fates in our hands” (factory farms, fashion, scientific advancement, exotic pet etc). This occurs mainly because (1) we are more intelligent, and (2) we act on our interests and if they conflict with the interests of other animals, there is a strong incentive to pass these interests over. Therefore, the relationship between humanity and AI could be similar.

Conclusion

By multiplying my estimates of the conditional probabilities of each hypothesis together we get 75% · 90% · 55% · 85% · 50% · 90% = ~14% probability of existential catastrophe from misaligned, power-seeking AI by 2070. However, as Carlsmith comments in the paper, the key point here isn’t the specific numbers. Rather, it is that there is a non-trivial and possibly significant risk that advanced AI will cause an existential catastrophe for humanity by 2070.

Appendix

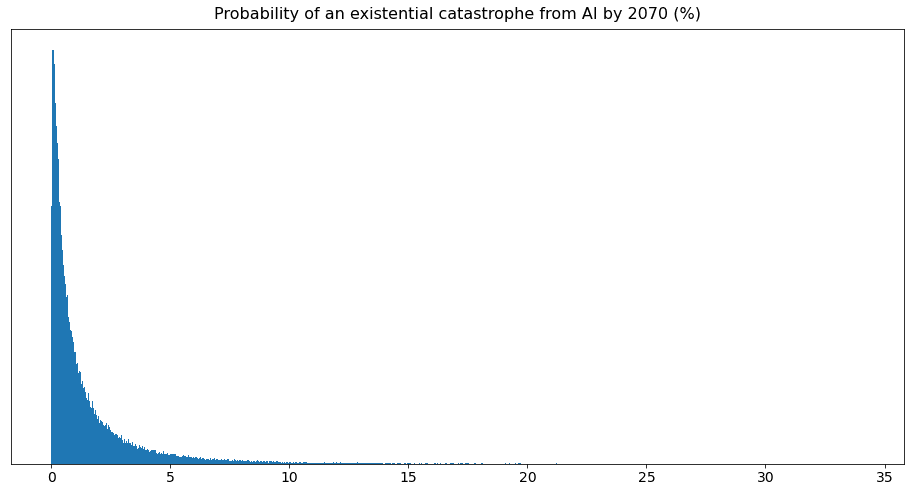

I created a model of the question by sampling random probabilities between 0.1 and 0.9 for all six variables and multiplying them. The resulting distribution is below:

Most of the estimates are between 0-5%. The lower bound estimate is 0.0001% (1 in a million), the average estimate is about 1-2% and the upper bound is ~53%.

The code for creating the distribution is below:

import random

import numpy as np

num_vars = 6

num_trials = 10**5

estimates = []

for i in range(num_trials):

probabilities = [random.uniform(0.1, 0.9) for n in range(num_vars)]

estimate = np.prod(probabilities)

estimates.append(estimate)

estimates = [e * 100 for e in estimates]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(16, 8))

ax.set_title('Probability of an existential catastrophe from AI by 2070', fontsize=16, pad=10)

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.tick_params(axis='x', labelsize=14)

n, bins, _ = plt.hist(estimates, bins=1000, density=True)