What these Thought Experiments Do

Cooperative dilemmas ordinarily leave these two reasoning patterns entangled, because they usually recommend the same action. The clone setup, and specifically Experiment B, is a controlled condition that separates them. It exposes a distinction that is real and consequential, but ordinarily concealed by surface agreement.

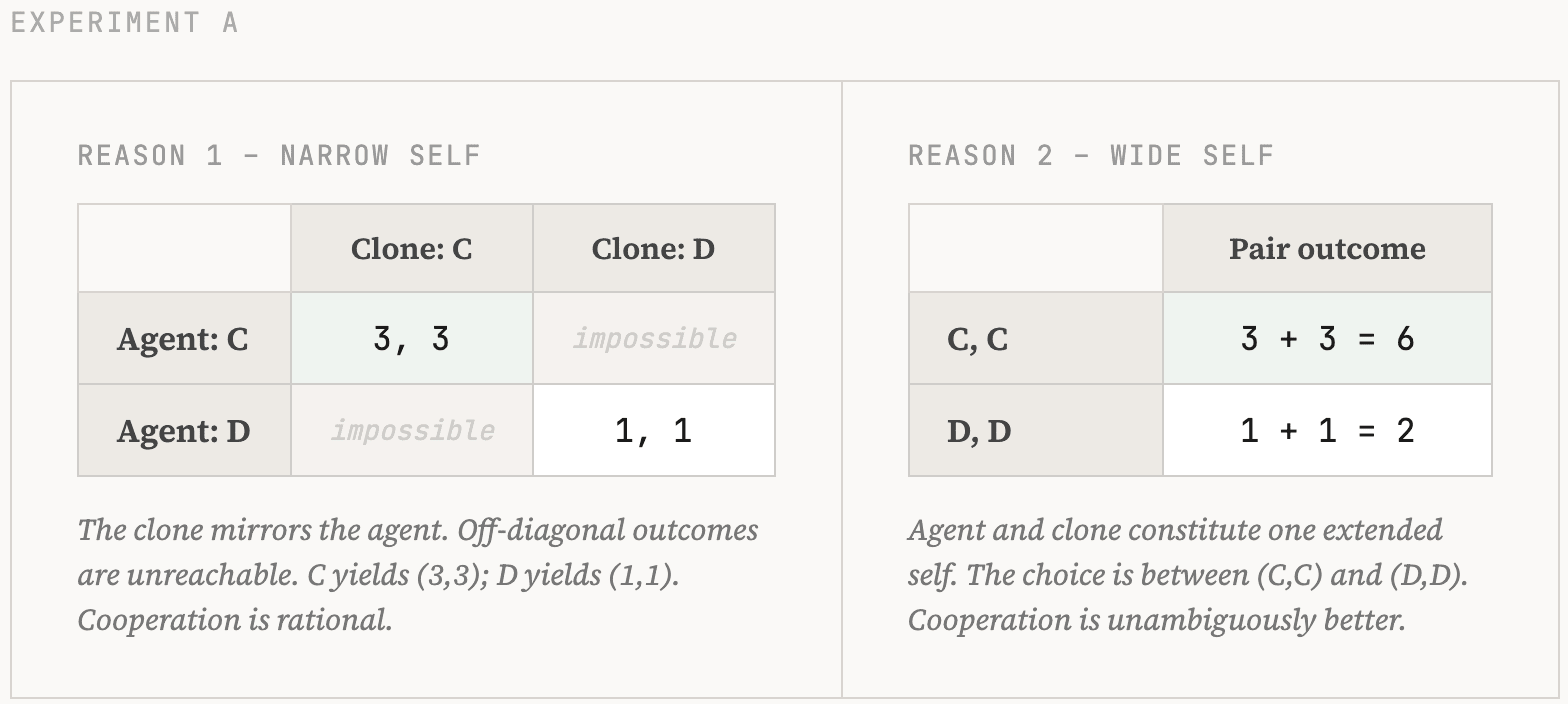

Experiment A

A rational agent is playing a one-shot prisoner's dilemma with their perfect clone: an entity that will make exactly the same decision they do. Why might the agent cooperate? Two distinct lines of reasoning both point toward cooperation:

Reason 1 (Narrow Self): "My clone will do whatever I do. If I cooperate, so will they, giving us both a payoff of 3. If I defect, so will they, giving us both a payoff of 1. Cooperation is the rational choice."

Reason 2 (Wide Self): "My clone is another instance of me. Harming them is harming myself. Cooperation is the only coherent choice."

Because both reasons recommend the same action, neither can be identified as the operative reason. Experiment B reveals the difference.

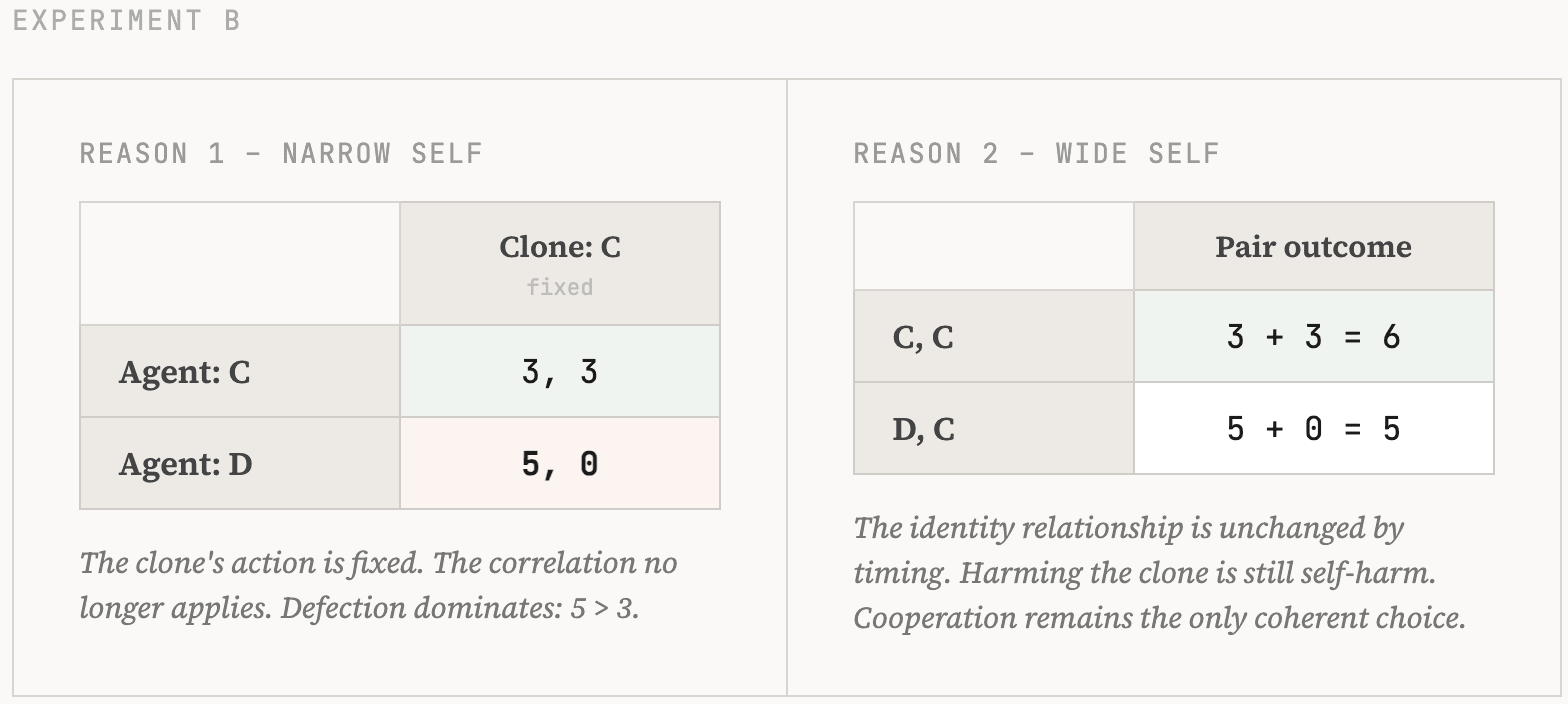

Experiment B

The agent now learns that their clone has already cooperated and its action is fixed. The two reasons diverge sharply:

Reason 1: "My clone has already cooperated. Defecting gives me 5; cooperating gives me 3. I should defect."

Reason 2: "My clone is still another instance of me. Taking 5 at their expense of 0 is still self-harm. I should cooperate."

Experiment B does not create this difference. It reveals a difference that was always there.

What the Boundary Determines

Each reason draws the boundary of self differently, and that boundary is what the thought experiment isolates. The divergence in Experiment B makes that boundary legible in a way that Experiment A cannot.

Reason 1 places the clone outside the self. The clone is part of the environment to be navigated in service of the agent's own interests. Cooperation, when it occurs, is instrumental: a function of expected costs and benefits.

Reason 2 places the clone inside the self. Agent and clone together constitute a single extended self, making defection incoherent on its own terms, not merely costly.

Two Modes of Cooperation

These two self-boundaries generate different cooperative dynamics. The distinction extends well beyond this thought experiment.

When the boundary excludes others, cooperation is conditional on modeled incentives. It is enforceable through rules and institutions, and scalable as a result. But agents are persistently motivated to game those rules, and the system grows fragile when incentives shift. This produces an ongoing arms race between defectors and enforcers.

When the boundary includes others, cooperation is conditional on recognizing shared identity. It requires no external enforcement and resists defection even when defection is available, but it is slow to develop, difficult to scale, and vulnerable to narrative reframing. Dehumanization, outgroup framing, and propaganda are, in this light, techniques for redrawing the self-boundary to exclude those who were previously inside it.

Most functional institutions layer both dynamics: rules and enforcement operating within a community with which members partially identify.