Epistemic status: Experimental. I'm developing these ideas as I write the sequence, drawing mostly from accumulated tacit knowledge and practical literature on group leadership. Use what makes sense for you, and ignore what doesn't.

Three stories about agentyness

1. "You go and solve the alignment problem!"

A friend of mine once attended a worskhop with MIRI, hoping for them to tell her how to use her math skills to assist their alignment research. Instead, they layed out the problem, gave her some open questions, and asked her to try and solve alignment herself. And thus, she went forth and worked on exactly that.

2. "So, where do I sign up for an impactful career?"

As I was told, people often come to EA's various career advice services hoping for a ready-made ten-step-plan that will automatically funnel them into an impactful career.

Alas, that is not how it works.

Nobody knows your strengths, weaknesses, and passions better than you. Nobody can know better than you where your comparative advantage lies. And, if you already have a degree: Nobody knows your area of expertise better than you, and how it relates to EA. And, first and foremost: The most impactful jobs tend to be those that didn't exist before people created them for themselves.

EA has figured out some things: People before you have put a lot of thought into cause priorization, into what makes a happy and impactful career, which pitfalls there are along the way, et cetera. You can climb on the shoulders of giants. But: You have to do the climbing yourself. And along the way, it's inevitable that you, yourself, will turn into another giant who pushes EA's collective frontier of knowledge a tiny bit further.

Sounds scary? It is. But it is not an impossible task - others have succeeded before you, and as EA goes, they are usually more than glad to help you along the way.

3. "Do you manage the other volunteers?"

Recently, a grantmaker asked me:

"So, what is your relationship to the other EA Berlin volunteers? Do you manage them?"

And my response looked somewhat like this:

"I... Am... Arp... Instigate? Hand out backpats and then they do stuff and grow in numbers? Nudge and make suggestions? Treat them like adult human beings and then they behave as such, and get more engaged with EA because it fosters their adultness? Ask them to do me favors? Ask them what they need to make happen what they think is needed in EA Berlin? Ahm, coordinate them, maybe?

I know what I'm doing, that it works even better than I hoped when I set out to do it, and I honestly don't know whether it would or wouldn't survive my parting. So, this post is an attempt at explaining what I'm actually trying to do in EA Berlin:

Scaling agentyness

There is a traditional take on management that I think is almost as prevalent in EA as in the corporate world. It goes somewhat like this:

"Most people are not agentic, some are. If you want to get work done, make the latter managers and the former their subordinates."

I think this is false. And dangerously so, as for most of the challenges humanity faces this century, we need a whole lot of agentyness from a whole lot of people. I'd like to suggest a different assumption. I think it is more useful than the one above, because people tend to live up to it when we expect them to. Here you go:

People are not unagentic by default, but the way we manage them in formal education, in traditional corporations, and in anything that we build by the example of these institutions make people unagentic.

So, here are some ingredients I've found to help tickle agentyness out of others:

1. Balance impact focus with psychological safety[1]

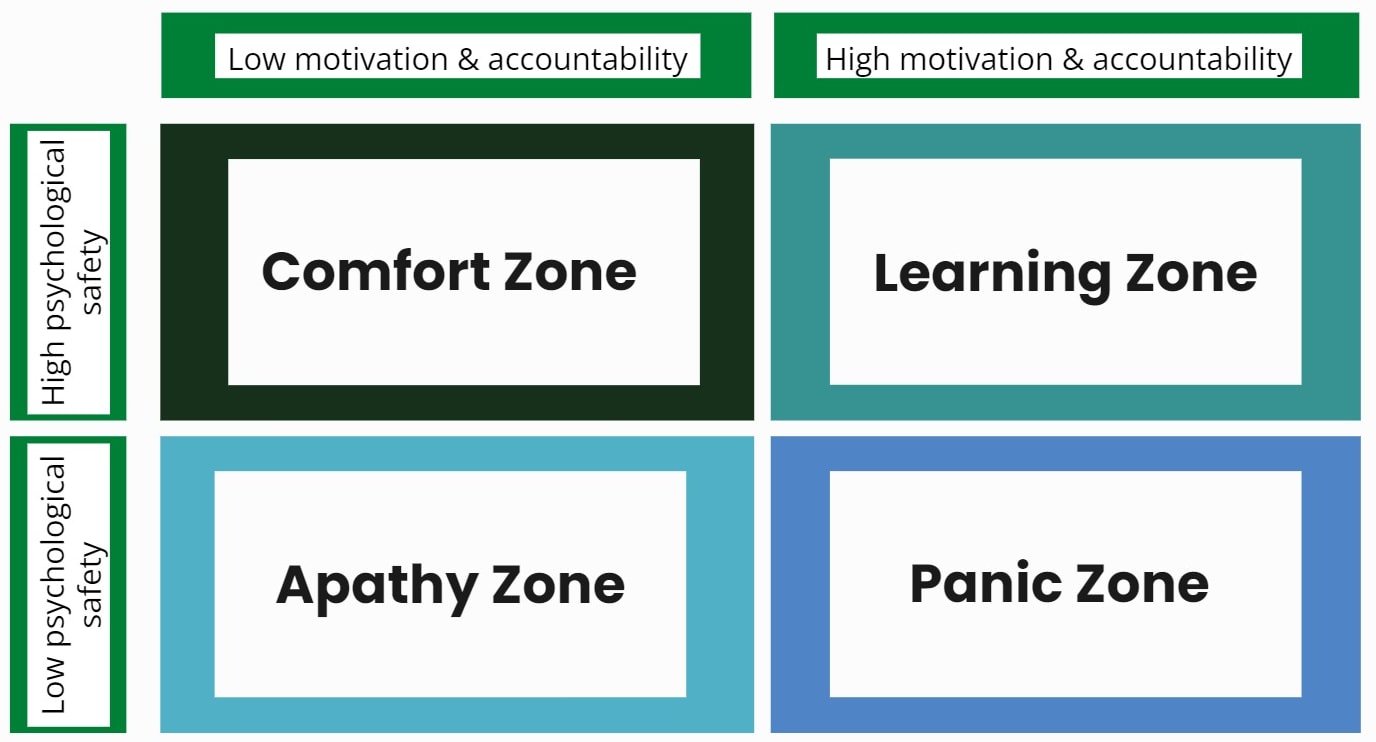

In her TED talk "Building a psychologically safe workplace", Amy Edmondson presents a two-dimensional graphic with motivation & accountability on one axis, and psychological safety on the other:

Motivation & Accountability vs. Psychological Safety. Recreated after a slide in Edmondson's TED talk

If we as community builders exclusively optimize for psychological safety, our community members end up in the Comfort Zone. Our meetups end up being lovely social gatherings, but little EA-aligned learning and planning happens. Worst-case, the more impact-driven individuals leave in disappointment.

However, if we neglect psychological safety, community members tend to end up in the panic zone. They experience impostor syndrome and burnout. They feel unheard when they voice their dissatisfaction, or don't dare to speak up in the first place - until they can't stay silent anymore and write very long anonymous EA forum posts. Worst-case, they lose their motivation entirely, (value) drift into the Apathy Zone, and drop out of the community entirely.

In her talk, Edmondson makes three simple suggestions for how to cultivate more psychological safety in organizations that already have a strong culture of accountability and performance. I find them fairly intuitive, so I'll just summarize them here:

- Frame the work as a learning problem, not an execution problem. For example, the leader of a meeting may set the group's expectations by saying: "We've never been here before. We don't know what will happen. We got to have everyone's voices and brains in the game."

- Acknowledge your own fallibility. This piece of advice applies to both team members and leaders. This makes speaking up safer for others as well. A useful sentence: "I may miss something here, so I need your help."

- Model curiosity. Ask a lot of questions in order to create a necessity for voice. Something you may want to have in mind: There is a difference between interested and interesting questions. Interested questions optimize for your own curiosity and learning; interesting questions for helping the asked person understand themselves and the problem at hand better. Either of them are useful in different contexts, and most of us tend to default to one of the two types. So, be clear about your intentions.

2. Inspire heroic responsibility

All these suggestions imply that psychological safety is, among others, instrumental for a different thing: Enabling people to think and decide for themselves. And if you go two steps further from there, you end up with a property Yudkowsky called Heroic Responsibility. As the LessWrong Wiki defines it:

"Heroic Responsibility is the responsibility to get the job done no matter what, including not shifting any responsibility for its completion on to others."

Or, as Harry explains it to Hermione in HPMOR, chapter 75:

"You could call it heroic responsibility, maybe,” Harry Potter said. “Not like the usual sort. It means that whatever happens, no matter what, it’s always your fault. Even if you tell Professor McGonagall, she’s not responsible for what happens, you are. Following the school rules isn’t an excuse, someone else being in charge isn’t an excuse, even trying your best isn’t an excuse. There just aren’t any excuses, you’ve got to get the job done no matter what.” Harry’s face tightened. “That’s why I say you’re not thinking responsibly, Hermione. Thinking that your job is done when you tell Professor McGonagall—that isn’t heroine thinking. Like Hannah being beat up is okay then, because it isn’t your fault anymore. Being a heroine means your job isn’t finished until you’ve done whatever it takes to protect the other girls, permanently.” In Harry’s voice was a touch of the steel he had acquired since the day Fawkes had been on his shoulder. “You can’t think as if just following the rules means you’ve done your duty.

I think as community builders, we might want to try and inspire people to take heroic responsibility - for only then are they fully equipped to decide what's right, and to follow through on it to the end. Here are some practical things I found useful for instigating (heroic) responsibility.

1. Facilitate, don't manage

One piece of the puzzle is encouraging your subordinates/volunteers to take full ownership for their tasks. Here's how I try and do that.

When somebody suggests something that I agree should be done, more often than not, my response looks somewhat like this:

"Yea, I think it would be good if that happened. But I'm currently running at capacity with the fundraising and all. How'd you feel about trying your hands at it?"

And when they take on the task, I try to avoid saying too much about how I think the job should be done. Instead, my first question usually is:

"How can I support you in doing this?"

I think that people who strive to manage their subordinates to excellence sometimes overlook that micromanaging and unsolicited advice are extremely costly.

If feedback is not delivered flawlessly (and even then), it tends to alienate people from their tasks by taking ownership away from them. It discourages them from trying new things. It destroys opportunities for learning, because it discourages subordinates from making and testing their own hypotheses for how to make something work.

And thus, if I were to monitor too much and too closely, I'd sacrifice a bit of a volunteer's long-term performance and motivation over and over again in order to make one single event go 5% more smoothly. I don't want that.

But does that mean I just let bad stuff happen without interference?

Not really. What I find way more useful than giving feedback and advice is debriefing events with the other organizers, through reflection rounds on eye level, where I'm just as much a participant as everyone else. My three standard questions:

- What went well?

- What could go better next time?

- What have we learned?

2. Make use of the Advice Process

The Advice Process is a well-tested process for decisionmaking in self-managing teams. I first found it described in Frederik Laloux' book "Reinventing Organizations", where even organizations with thousands of employees are described to use it. And, almost simultaneously, I got to see its full force in action in how the Burning Man-community organizes.

A short description of the Advice Process by Burning Nest:

"The general principle is that anyone should be able to make any decision regarding Burning Nest.

Before a decision is made, you must ask advice from those who will be impacted by that decision, and those who are experts on that subject.

Assuming that you follow this process, and honestly try to listen to the advice of others, that advice is yours to evaluate and the decision yours to make."[2]

Since I first encountered it, the Advice Process has become the guiding star for all my EA organizing. I find using the process in this context remarkably elegant because it merely explicates how many things in EA are already handled implicitly. And, where things are not done like this, making the Advice Process explicit props up a greater vision for how things could be, if EA were to reach the full potential of its innovative forms of organizing.

If used competently, the Advice Process can allow people to move independently, responsibly, and effectively even within an organization that consists of thousands of other people.

At the same time, it can reduce the risk of people getting stuck in decision paralysis, by telling them that there is no-one they have to ask for permission. And, because actively seeking advice is implied, it may prevent EAs from invoking the unilateralist's curse by blindly starting something that others decided for good reasons not to make happen.

Of course, not where infohazards are involved. But, I think there are a significant amount of non-infohazardey areas of EA that could be lubricated by making the Advice Process the norm.

3. Develop good conflict resolution strategies

If you just follow orders, there will be no conflict. If you work together with other people on eye-level, however, disagreements are inevitable. Not only about facts, but also in regards to values, priorities, visions, or ways of communicating. The more you give up on traditional hierarchies, the more important it gets to know a thing or two about conflict resolution.

In 1965, Bruce Tuckman proposed an infamous model of group development. According to his observations, any group of people tends to evolve through four consecutive stages: Forming, storming, norming, and performing.

- Forming: Everything is new and exciting. Group members get to know each other, discover commonalities, and start working together. Group performance is reasonably high.

- Storming: Group members begin to discover differences in opinion, work flow, personalities. Covert and open conflict erupts. Some people might decide to leave the group. Performance goes down, because the interpersonal problems eat so much attention.

- Norming: Roles, rules, routines, and responsibilities get negotiated. Those who stayed find new trust and a good rhythm for working together. The group finds back to good performance.

- Performing: Everybody in the group knows what they have to do, and how to interact with one another. The group reaches peak performance.

Every time a person joins or leaves a group, its whole relationship structure shifts and it has to go through a version of these phases again.

The main takeaway from this model I'd like you to consider: Avoiding conflict is usually not actually good for a group. Getting stuck in the Forming-phase keeps a group cold, distant, and below peak performance. Instead, you might want to offer tools that help the group members address their differences constructively. This is true for local EA groups just as much as for teams in EA orgs. And, I have the impression that in some sense, EA at large is currently going through the storming/forming-phases after the last year of scandals.

I listed some tools that might help EAs deal with conflict in an earlier post.

However, the most useful one I've found so far are Withholds. Here's what that is, cited from Authentic Revolution's Authentic Relating Games Manual:

"Withholds are things that we have left unsaid in a relationship or connection with another person. Sharing them regularly, before they build up, is the absolute best way I know to maintain relational health in a team, community, or relationship. These are a lifetime practice for me.

Withholds can either be given in the full group, like Truths, or one-on-one at any time. To share a withhold, first ask the person if they’re open to it, and then set context for why you want to share.

For example:

“Sandra, may I share a withhold with you? We had a moment last week that really

didn’t feel good to me, and I’ve been holding a judgment about you since. I’d like to come back into connection.”Then, share whatever you haven’t been saying with the person. Example:

“I was really pissed off when you overrode me in our planning meeting. I felt like I

didn’t matter to you, and then I had trouble participating in the rest of the event

afterwards. How is that to hear from me? Did you notice that moment? What was

happening for you?"Give your partner time to respond, and continue going back and forth until you both feel complete."

Last words

As always, reverse this advice as needed. If any of this seems reasonable to you, try it. If it seems weird but interesting, debate it. If it doesn't make sense and seems dangerously wrong, by no means try to implement it, and let me know - because of course, you might be right.

- ^

For more on what psychological safety is and some properties of EA that curtail it, see my previous post on the topic. Thanks to Katarina Hahn for reminding me of Amy Edmondson's video.

- ^

Thank you for this lovely post Severin!