Defining key cause areas - such as global poverty, animal suffering, and existential risks - is an important element of effective altruism, in part because it has helped effective altruists to identify the most effective organizations and interventions in each area. However, addressing one cause area at a time without considering the ways in which its interventions affect other cause areas - for better or worse - can have a negative impact on the overall effectiveness of EA, a consequence that is often not considered. Invoking an Intercausal Impacts analysis, this article makes a case for establishing food systems transformation/meat reduction as a cause area in its own right.

Effective Altruism’s ‘divide-and-improve’ approach

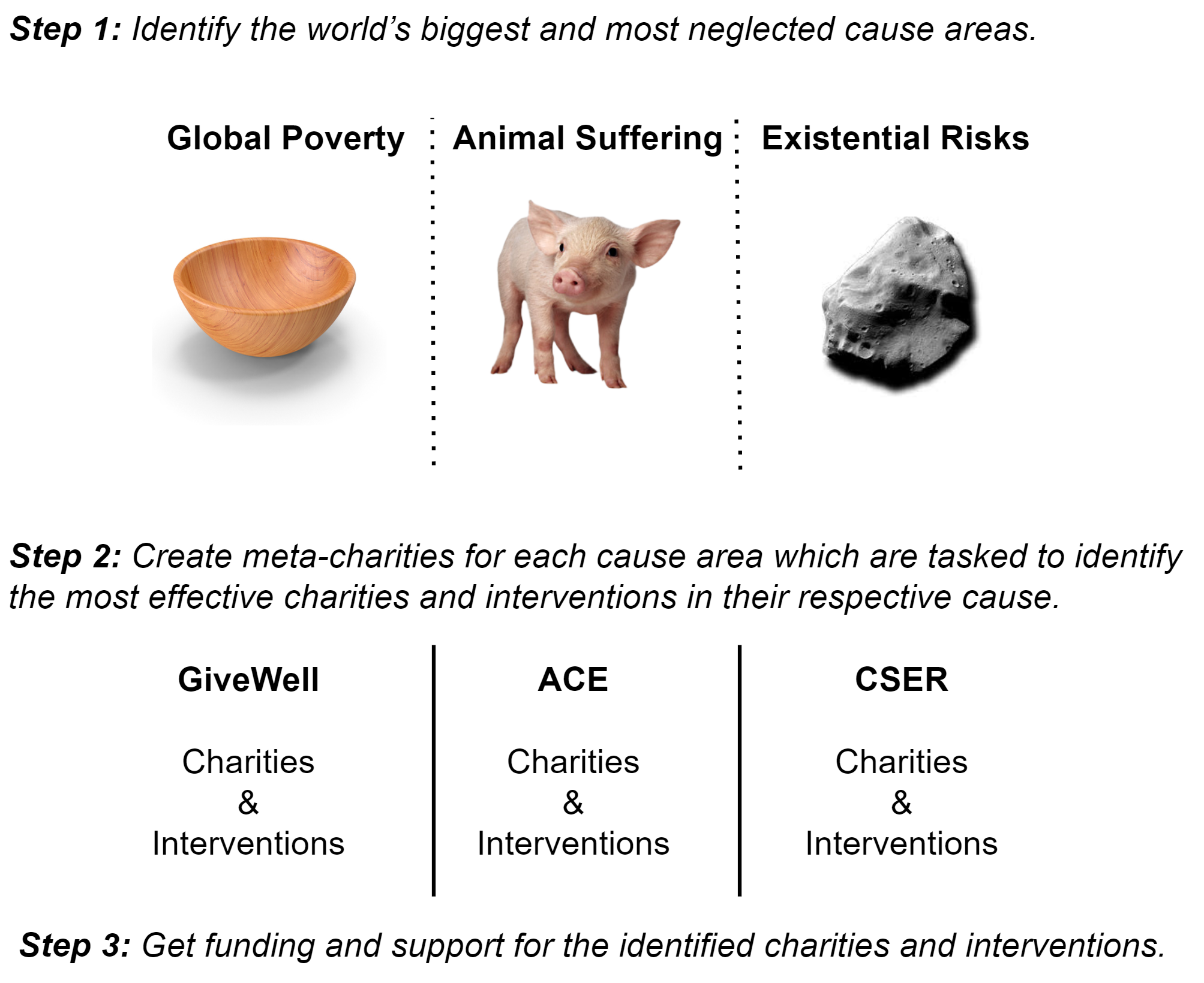

Effective Altruism aims to improve the world as effectively and efficiently as possible. To achieve this goal, global problems are usually split up into different cause areas. Each cause area is analysed on the criteria triad of importance, tractability, and neglectedness. Such an analysis is what led to causes such as ‘global poverty’ (improving the economic or health situation of the least affluent), ‘animal suffering’ (reducing non-human suffering) and ‘existential risks’ (increasing the chances of survival for future generations) becoming prominent focus areas of EA. And the list of cause areas is growing.

This ‘divide-and-conquer’ or rather ‘divide-and-improve’ approach has proven very useful so far in EA thinking and theorising, and has led to the establishment of several meta-charities for each of the three cause areas highlighted above. The goal of these meta-charities is to research, analyse and promote those organisations and interventions that are best suited to solve the specific problems within their respective cause area. While the meta-charity ‘GiveWell’ looks into the most effective interventions to help the global poor, ‘Animal Charity Evaluators’ tries to identify the most useful interventions to reduce animal suffering, and the ‘Centre for the Study of Existential Risk’ identifies and works toward reducing the risks of humanity extinction and civilzational collapse.

Here is a simple overview of this process in three steps:

Drawbacks of the divide-and-improve approach

While this approach has many benefits and has helped improve the state of the world tremendously, it comes with crucial and so far often overlooked drawbacks. There are two ways this approach might actually work against EA’s overall goal of creating the most good in the world - both of which involve what I call ‘Intercausal Impacts’, i.e. the overall impact of a given organisation or intervention not only on its respective primary cause area but on all cause areas aggregated.

- Overrating: Interventions (and organisations) that are regarded as very efficient in one cause area might have negative spill-over effects and actually do damage in other cause areas. Thus, their overall impact might be significantly less positive (and in some cases even net negative) than is immediately apparent. Ignoring negative spill-over effects on other cause areas implies an overrating of the intervention or organisation in question.

- Underrating: Interventions (and organisations) that have a positive impact on various causes but are not amongst the most effective in any particular cause area will receive little or no attention and support although their overall cost-effectiveness across cause areas might be superior. Ignoring positive spill-over effects on other cause areas implies an underrating of the intervention or organisation in question.

Specialisation and integration

Both problems stem from specialisation and narrowing down of focus. Specialisation is an important and inevitable step in all instances of cultural progress. However, as it often comes at the expense of a more holistic perception and analysis, it can also have negative consequences. Specialisation in the medical profession has led to specialists for shoulders or knees. But sometimes, pain in your shoulder stems from a problem in your knee or elsewhere. The root cause of problems affecting certain areas sometimes lie elsewhere and require a holistic approach and an understanding of the broader context. While the knowledge generated through specialisation takes us to the next level, integrating this knowledge into a more complex and holistic perspective is essential in order not to generate new, unintended problems - or failing to identify additional positive impacts. This means that promoting (a limited number of) interventions within the current ‘divide-and-improve’ approach of the EA meta-causes probably does not lead to the best overall outcome in the world.

An abstract example

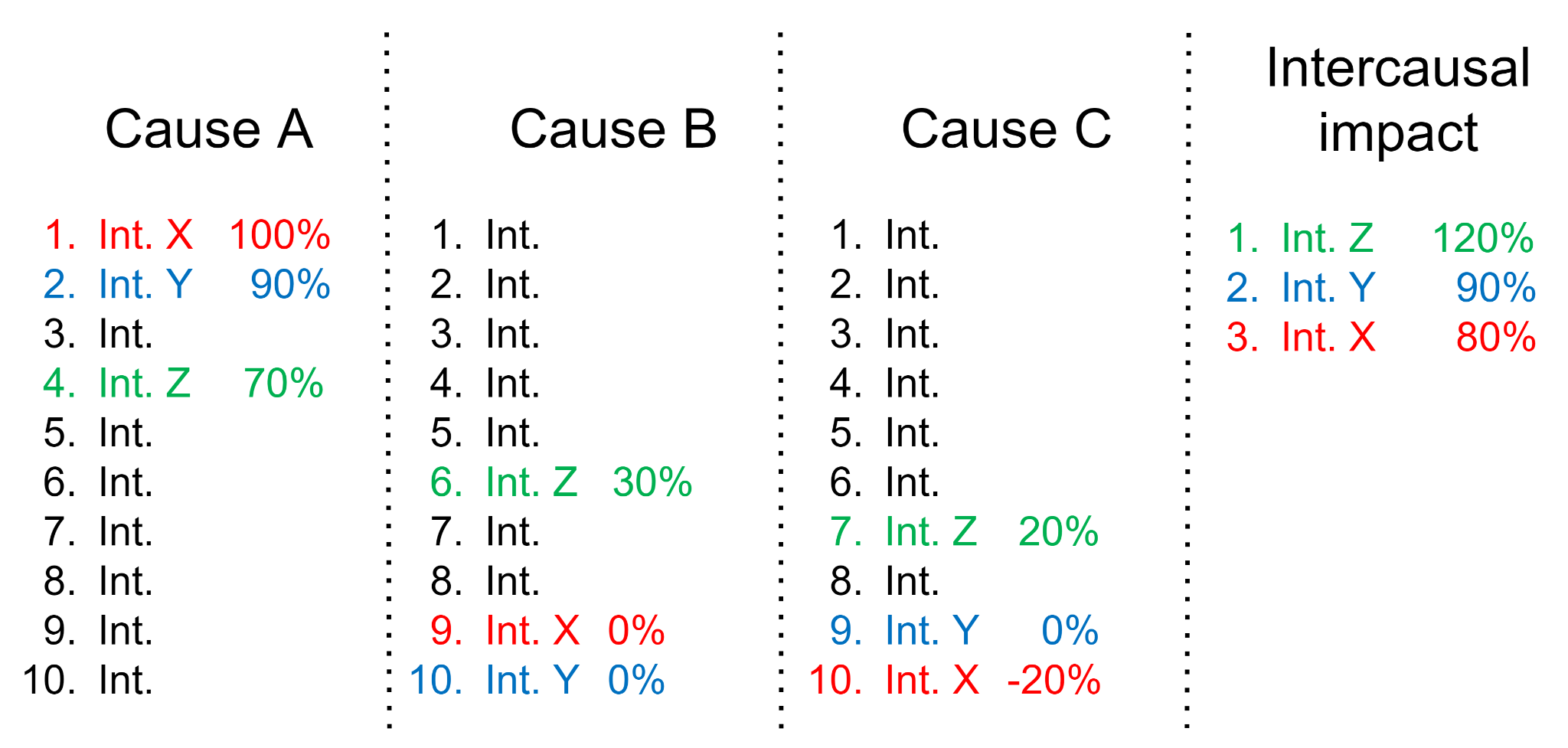

To illustrate this point let us now consider an abstract example with concrete figures. Consider three cause areas called A, B, and C, as well as three interventions called X, Y and Z. The cost-effectiveness of each intervention (in terms of all resources invested) is stated in percentage points, with 100% for the currently most effective intervention for a specific cause area. Thus the rating of the three interventions might be as follows:

X: 100% (the most effective intervention regarding cause A)

Y: 90% (this intervention has an effectiveness of 90% compared to intervention X within cause A)

Z: 70% (this intervention has an effectiveness of 70% compared to intervention X within cause A)

At first glance, it seems perfectly reasonable for the meta-charity of cause A to recommend intervention X the most, also promote intervention Y to some degree, but probably not to provide much support to intervention Z or any of the even less effective interventions that may exist further down the line. Some might argue that the difference between the most effective intervention and the second and third most effective is in most cause areas much larger than in this example. This might initially be true but with more and more funding going towards the most effective intervention the added impact of each additional dollar will naturally go down, pushing the effectiveness closer and closer to the more neglected interventions.

Now let’s take a closer look at the hypothetical intercausal impacts of each intervention. To this end, we analyse the impact of each intervention - not only with regard to their respective cause area alone, but with regard to all affected cause areas combined. Call this the total impact, or Intercausal Impact. The basics of our evaluation are straightforward: If the impact of an intervention on a certain cause area is negative, the value is negative. For example: B-20% implies that the impact of this intervention on cause area B is negative in the magnitude of -20% compared with the positive impact of the most effective intervention in cause area B. Technicalities aside, comparing different causes is inherently a tricky endeavour. Comparability and commensurability on quantitative and qualitative levels are notoriously difficult to determine. However, let’s assume, for the sake of the argument, that all causes are equally important and that the Intercausal Impact, that is the total impact of an intervention across all causes, can be expressed by adding all impact values of all cause areas. So, taking into account our interventions X, Y and Z for all three of our abstract cause areas A, B and C, the overall picture in our hypothetical scenario may look like this:

Applying an Intercausal Impacts analysis that takes into consideration all impacts across all cause areas, the original effectiveness of our three interventions changes significantly. Our former top-ranking intervention X for cause area A now only yields an Intercausal Impact result across all causes of 80% due to its negative impact in cause C. Intervention Y - which has neither positive nor negative impacts on other cause areas - has an unchanged total effectiveness of 90%. Interestingly, intervention Z, which did not make it into the top-three most effective interventions in any individual cause area in our original analysis, but has positive impacts on all three cause areas, now reaches a global effectiveness of 120% in our Intercausal Impacts analysis.

Looking at the overall outcome of our example, it becomes clear that, by ignoring Intercausal Impacts, our original analysis would fail to correctly identify the overall most impactful intervention. This is highly relevant not only from a theoretical perspective, but from a practical one as well. Because in the real world, cause areas do not necessarily exist in isolation but often intersect, and the impacts of interventions (both positive and negative) are not limited to their respective cause areas but can be intercausal.

What does this imply? First, we need to expand our analysis beyond certain cause area boundaries to arrive at more informative insights when it comes to the overall good we can create in the world. Second, on a meta level, it seems advisable to take the recommendations of meta-charities that only focus on one particular cause area with a grain of salt for the time being. While specialisation has made a huge difference for their respective cause areas, we should encourage them to expand their analysis and thus consider the impact that any given charity or intervention has on the world from a more Intercausal Impacts perspective. Of course, this requires expanding and exchanging expertise beyond one’s own area of specialisation.

While there may be several instances of interventions that our current approach overrates or underrates, I would like to illustrate the Intercausal Impacts analysis suggested here with a real-world example I am sufficiently familiar with.[1]

Instances of underrating: Meat reduction and food systems transformation

One category of underrated interventions (and organisations) are those that help shift the global food system away from animal products towards plant-based or cultured alternatives. Traditionally in EA analyses, these interventions (and organisations) are primarily assessed and evaluated based on their contribution to reduce animal suffering. Compared with corporate campaigns aimed at increasing the welfare of farmed animals, interventions that focus directly on meat reduction and food system transformation are often seen as less tractable, less measurable and/or less cost-effective in this single dimension. As a consequence, they also receive relatively little support and funding.

This presents a stark contrast to the vast animal suffering caused by animal agriculture. Every year, about 80 billion land animals[2] and 2.3 trillion marine animals[3] are slaughtered, while animal agriculture is also responsible for 70% of species extinction[4], which implies vast individual suffering of wild animals.

However, the positive effects of replacing animal products are not restricted to reducing animal suffering. As Maya Mathur of Stanford University, Jacob Peacock from Rethink Priorities and co-authors write, “Several exigent societal issues could be mitigated by reducing global consumption of meat and animal products and encouraging predominantly plant-based diets in their place. Authoritative enjoinments for such a dietary shift have highlighted its potential to improve public health [1,2,3,4,5,6], reduce risks of zoonotic pandemics and antibiotic resistance [7], curb environmental degradation and climate change [3,4,5,6,8], and limit the preventable suffering and slaughter of approximately 500 to 12,000 animals over the lifetime of each human consuming a diet typical of their country [6,9].” This list can easily be extended by adding the positive impacts of climate change mitigation on the wellbeing and life expectancy of humans and wild animals through preventing or mitigating droughts, floodings, heat waves, etc.; secondary impacts of pandemics and antibiotic resistance prevention on social cohesion and economic prosperity; or food security improvements in times of (political) crises through reduced dependency on inefficient animal-based sourcing processes.

Despite its real and potential impacts, however, reducing our reliance on animals for food continues to be a highly neglected intervention in many areas. While animal agriculture contributes 20% of GHG emissions,[5] not even 2% of the global budget to mitigate climate change is directed towards reducing the global production and consumption of animal products.[6] A recent study by the Boston Consulting Group has demonstrated that “for each dollar, investment in improving and scaling up the production of meat and dairy alternatives resulted in three times more greenhouse gas reductions compared with investment in green cement technology, seven times more than green buildings and 11 times more than zero-emission cars.”[7] And Project Drawdown, which assesses climate solutions, places plant-based diets in the top three of almost 100 options.[8]

Besides its significant contribution to climate change, animal agriculture is also responsible for 80% of rainforest destruction[9] and uses 80% of agricultural land.[10] It contributes to world hunger and water scarcity through inefficient use of valuable resources, with 75% of the global soy harvest[11] and 30% of fresh water[12] consumed by animal agriculture. Given the broad negative effects of animal agriculture, it seems likely that it also causes significant amounts of wild animal suffering (e.g. due to the use of insecticides, habit loss, droughts, climate change, etc.)

So even if interventions focusing on meat reduction and food systems transformation should turn out to be not the most cost-efficient interventions when it comes to animal suffering (and even that is still up for debate), applying an Intercausal Impacts analysis would reveal their true total impact scope across various cause areas.

Interventions that focus on reducing the suffering of farmed animals often increase the environmental and climate footprint of animal products while interventions that focus on reducing GHG emissions of animal agriculture (e.g. switching from beef to chicken consumption) often lead to more animal suffering. These negative spillover effects can be avoided by focusing on reducing the general consumption of animal agriculture altogether.

Conclusion

Overrating, that is ignoring the negative spill-over effects of an intervention on other cause areas, can result in insufficient and unrealistic overall assessments - just as underrating, that is ignoring the positive spill-over effects. If our ultimate goal is using the resources available to us to create the most good in the world overall - and not just in one cause area - we should take a more holistic view and consider broadening our impact analysis to include Intercausal Impacts. And taking into consideration the Intercausal Impacts of food systems transformation, in particular the reduction and replacement of animal products, provides a strong reason in favour of acknowledging it as a cause area in its own right.

- ^

Having worked on food systems transformation for the last 15 years, I also acknowledge the possibility of my perception and representation here being biased to some extent. This is why I invite constructive critique and feedback to update where relevant.

- ^

FAOSTAT (2022).

- ^

Mood, Brooke (2019); FAO (2021).

- ^

Maxwell et al. (2016).

- ^

Xu, X., P. Sharma, S. Shu, et al. (2021): Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods. Nature Food 2(9), 724–732. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x

- ^

Estimate based on numbers by Climate Policy Initiative (2021): Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021. Available at: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Full-report-Global-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance-2021.pdf [Accessed: 19.07.2022]

- ^

Morach, B., M. Clausen, J. Rogg, et al. (2022): The Untapped Climate Opportunity in Alternative Proteins. Food for Thought. Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/combating-climate-crisis-with-alternative-protein [Accessed: 19.07.2022]

- ^

Project Drawdown: Table of Solutions. Available at: https://drawdown.org/solutions/table-of-solutions [Accessed: 19.07.2022]

- ^

Nepstad, Stickler, Filho, Merry (2008).

- ^

Poore, Nemecek (2018).

- ^

Chathamhouse (2016).

- ^

Hoekstra (2014).

Hi Sebastian,

Great post! I do think indirect effects are underrated.

Reducing the consumption of animals has lots of benefits, but I do think there are some negative ones too:

I have a draft for a question-post describing the multiple effects of decreasing the consumption of animals. Comments are welcome!

I like the idea of being more intersectional in our thinking on how to approach the assessment of specific interventions.

On the topic of food, some ALLFED colleagues and I recently gave a workshop on the intersections between different EA cause areas:

On the topic of interventions improving various cause areas simultaneously, some of my colleagues have published scientific articles arguing that the type of work we're doing appears to be highly cost-effective for improving both the long-term future and saving lives in the short term / current generation. Obviously consider a conflict of interest as I work for ALLFED, but this seems very pertinent to the topic of the post.