If we want to improve the world (and ourselves), we need to start by changing the way we live — our habits and behaviors. In this talk, Spencer Greenberg, founder and CEO of ClearerThinking.org, discusses why behavior change matters and techniques we can use to get better at it.

Below is Spencer’s talk, which we’ve lightly edited for clarity. You may also watch it on YouTube or read it on effectivealtruism.org.

The Talk

Thank you so much for having me. I'm really happy to be here.

If you consider humanity’s problems from 3,000 years ago, you'll note that many of them have to do with the inability to understand and control the physical world.

They include things like how to get your crops to grow, treat infection, and stop the spread of disease.

But as science advanced, our problems became increasingly of a different kind. They involve a substantial amount of behavior change that makes them different from many of the problems we had before.

Heart disease is the No. 1 cause of death worldwide, according to the World Health Organization’s 2016 figures. Depression is the No. 1 cause of disability worldwide, according to the World Health Organization’s 2018 figures. Both of these, of course, have significant genetic and environmental components, yet they also can be substantially improved via behavior change.

For heart disease, exercise, diet, and medical compliance can help. For depression, cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral activation are both evidence-based techniques [that can help].

But with scientific progress, behavior change has actually created a whole new class of threats.

Nuclear war, global warming, and bioterrorism from new viruses are, fundamentally, really about behavior. With that in mind, I want to talk about what I'm going to call “positive behavior change,” which is behavior change designed to improve yourself or the world.

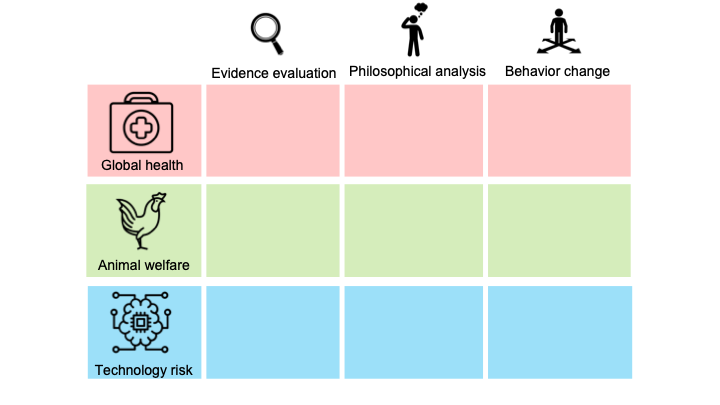

If you think about the classic three cause areas in effective altruism (EA) — global health, animal welfare, and technology risk — one interesting thing we can do is look at capacities that cut across all three areas.

One of these capacities is evidence evaluation: how we [interpret] evidence and decide how strong it is. I think we can agree that this cuts across all EA work. For global health, we ask questions about the extent to which bednets reduce malaria. For animal welfare, [we consider whether] cage-free campaigns are cost-effective for reducing [the number of animals in cages]. For technology risk, AI researchers forecast [the potential effects of] developments in AI. So, [evidence evaluation] is one capacity that we need in a community that's trying to do good.

Another capacity is analytical or philosophical analysis. In global health, we have questions like “When forced to choose, should we save children or save adults?” In animal welfare, we ask, “Are fish, chickens, pigs, and humans equally capable of suffering?” With technology risk, we have questions like “How difficult would it be to control a superintelligent AI?”

What I'm proposing today is that there's a third capacity that we talk about a lot less, but is critically important to many of the things we're trying to do: the capacity to change behavior. Getting people to use bednets in high-malaria areas is fundamentally a new behavior we're trying to create, as is getting consumers to accept plant-based and clean meat products in the animal welfare space. A behavior change in technology risk is getting AI researchers to deeply consider possible risks of their work.

Behavior change is not just important at the level of these causes; it's also really important for you.

If you want to have more of an effect on the world, it's helpful to learn how to change your own behaviors to do so. Plus, being able to change undesirable behaviors can make you significantly happier.

Unfortunately, behavior change doesn't happen automatically.

Imagine telling yourself, "I should really go to the gym every day." Well, I think we all know that just having that thought, and even believing that you want to do it, is a far cry from actually going to the gym every day. It’s just not going to happen automatically.

It's also interesting to think about this in a global-health context.

How would you go about getting people in rural communities to add chlorine to unsafe drinking water? You just give them chlorine, right?

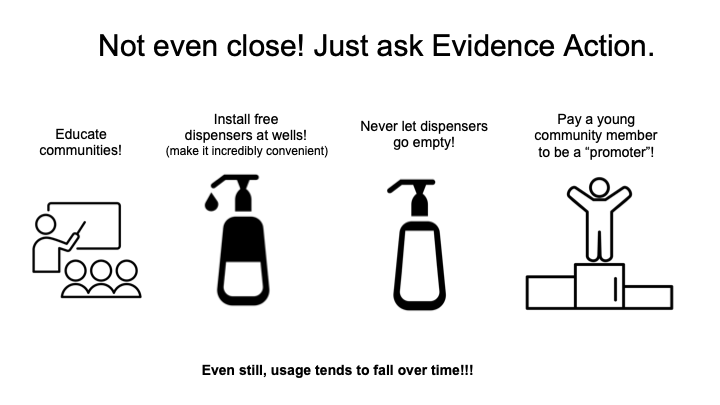

If you ask Evidence for Action, they'll tell you that’s not even close to what you have to do.

Evidence for Action creates educational campaigns to try to get people to use chlorine to make their water safer. They went into communities and educated them, as well as giving them the chlorine. They determined that if you put dispensers of free chlorine where people are pulling their drinking water, it is incredibly convenient to use. The chlorine is right there when you need it. It reminds you to use it.

You might think that [by making the chlorine free and convenient], people would engage in this behavior. But it’s not enough. If the dispensers were emptied, not only were people unable to use the chlorine [in that moment], but they stopped using it altogether [even after the dispensers were refilled]. Maybe this is because people fell out of the habit of using the dispensers. Maybe it’s because people stopped having faith in the reliability of the chlorine dispensers.

In any case, Evidence for Action then went through a lot of effort to make sure that the chlorine dispensers would always be kept full. Even that wasn’t enough. The organization ended up giving people who lived in the community a t-shirt and paying them to promote chlorine use. They studied multiple variables associated with which promoters did the best job [to help ensure they selected effective promoters]. But even with all of these behavior change strategies, they found that while they could get people to use the chlorine, their use tended to trail off over time. Behavior change can be a really significant challenge.

I want to summarize what I’ve covered so far:

1. Positive behavior change is an important part of most attempts to improve the world today.

2. It can be very hard to do it well.

3. I believe this is significantly under-discussed. [Those of us in the EA community] don't usually conceptualize ourselves as trying to change behaviors, even though I think that is a significant amount of [what’s involved in trying to help the world].

But does it make sense to talk about improving capacity at behavior change? Can someone become an expert in behavior change? I see it as analogous to evidence evaluation. We can all agree that organizations working effectively to improve the world are often good at evidence evaluation. I think we can also agree that they could still benefit from outside expertise — a statistician, data scientist, epidemiologist, or someone who is an expert in experimental design.

I think the same thinking applies to behavior change. You can imagine people who are experts in the psychology of behavior change and who understand the barriers to changing behaviors helping organizations that are already very good at behavior change get even better at it. Experts could help organizations figure out new strategies that they may not have considered.

[There is already some evidence that this works.]

Behavior change experts in organizations like Behavioural Insights, the Center for Advanced Hindsight, and ideas42 have been working with different nonprofits and government organizations to improve positive behaviors more effectively. And a recent series of randomized controlled trials shows that their work creates positive outcomes in a variety of different ways.

In my own work at Spark Wave, I see the power of behavior change all the time. We create new companies from scratch that are designed to help solve problems in the world through a social science lens. Then, if a product is promising, we recruit a values-aligned, passionate, driven CEO to work with us and ultimately spin the product out into a new company.

The work we do tends to break into two categories. One is improving people's lives through behavior change. We do this with products like UpLift, which aims to provide the best self-help for depression in the world, and Mind Ease, which aims to reliably help people suffering from anxiety feel better whenever they need to. We also created Clearer Thinking, a website that has more than 20 free tools and training programs to help you make better decisions and better understand yourself.

[The second category centers on] accelerating the study of behavior change and humans more generally. For this, we have products like Positly, which is a new platform for recruiting people for studies. Positly aims to make it easy to get the right participants, at the right time, to do the right thing. GuidedTrack is another product of ours. It’s a new language for building behavioral interventions and complex studies.

What can you do to use behavior change more effectively? First, if you work for or run an organization, I think it's helpful to (1) clearly define your organization’s behavior change challenges, (2) be sure to view them as behavior change challenges, and (3) potentially even bring in external behavior change expertise to help you meet those challenges.

Second, if you want to change your own behavior to be more effective or happier in your life, I would advocate that you apply behavior change strategies systematically.

But what does it mean to apply behavior change systematically? For the rest of this talk, I'm going to make behavior change extremely concrete.

There are a number of different frameworks for trying to create behavior change. I'm going to walk you through some of them. I’ll then point you toward a new resource that Spark Wave launched. It summarizes all of these different frameworks and attempts to make the principles of behavior change very easy to understand.

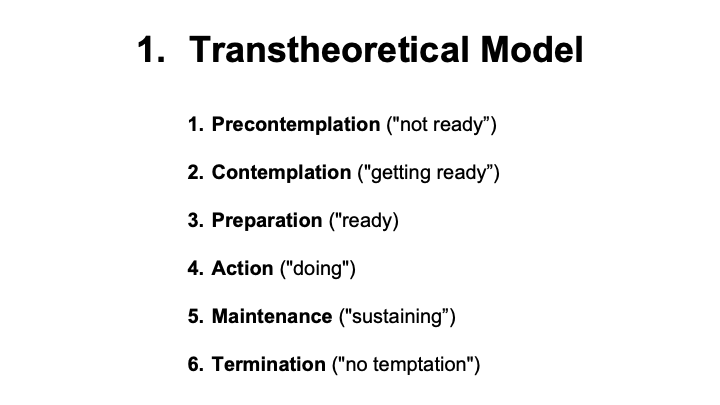

The first framework I’d like to discuss is the transtheoretical model. The main idea is that people go through different stages in a behavior change, such as:

* The precontemplation phase, during which someone is not yet ready to change

* The contemplation phase, during which they're getting ready but not actually taking action

* The preparation phase, [during which people intend to take action and start taking small steps to change]

There are several more stages. What's neat about [this framework] is you realize that different techniques are appropriate when people are at different stages. Also, you can conceptualize [the change process] as people move from one stage to the next.

A second framework that I think is interesting is the theory of planned behavior.

This framework identifies three major factors involved in behavior change:

* A person’s attitude toward the behavior change: Do they think it's good and do they desire it?

* The subjective norm: Do the people this person cares about approve or disapprove of the behavior?

* Perceived behavioral control: Does the person believe that they can actually achieve this behavior?

Together, these three factors influence someone's intention to engage in the behavior, and that ultimately leads to behavior change.

A third framework I want to tell you about is the EAST model by the Behavioural Insights team.

EAST packages some useful behavior change techniques into a simple-to-use format. So, if you're trying to change a behavior, you want to try to make it:

* “E” for easy, by doing things like applying defaults and reducing hassle

* “A” for attractive, by attracting attention, providing incentives, etc.

* “S” for social — for example, by showing that most people have already engaged in the behavior

* “T” for timely — for example, by prompting people when they're most likely to be receptive to engage in the new behavior

Finally, I want to introduce a behavior change framework from Spark Wave.

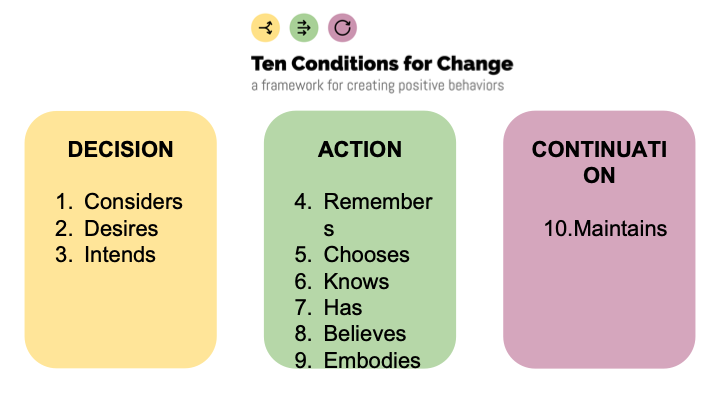

It’s called “the “10 conditions for change framework.”

We developed this framework to help you pinpoint exactly why a behavior is not occurring either in yourself or in a population. It allows you to analyze what’s blocking a behavior change, so that you can determine which strategies to apply to remove those blockers.

It's designed to be a sufficient model for behavior change; if all 10 conditions are jointly met, it's very likely that someone will engage in the behavior.

I should say that this is a work in progress. I can't guarantee we won't add an eleventh condition later.

If someone is not engaging in a behavior, that means that one or more of these 10 conditions are not being met.

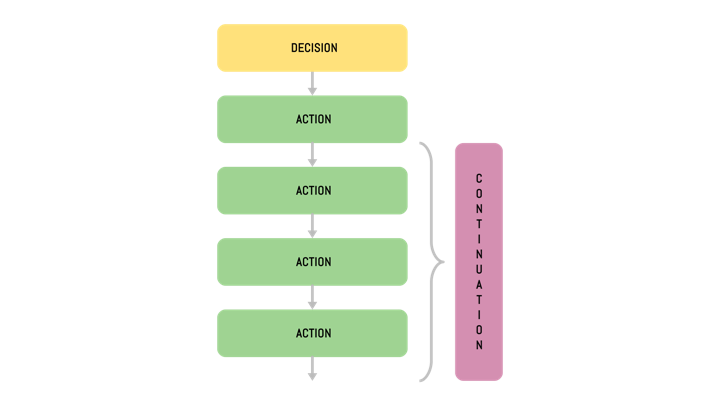

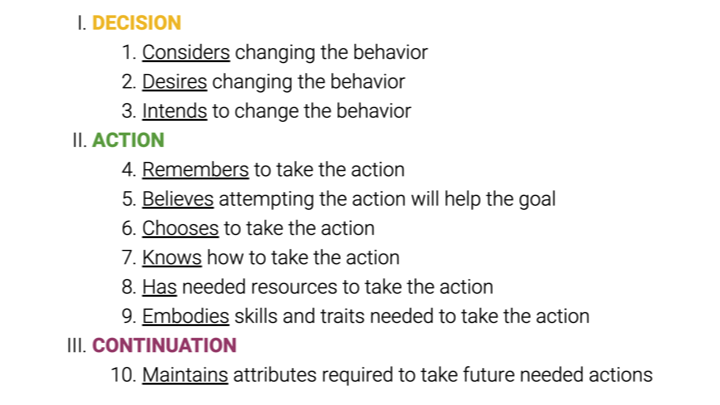

The framework allows you to diagnose which of blockers are occurring. The conditions are grouped into three phases:

* The decision phase, during which someone decides to do the behavior. As we'll see, we need three different conditions to be met in the decision phase.

* The action phase, which involves a series of actions across time. For each action, six different conditions must be met. For any given behavior, there are probably many different sequences of actions that would be sufficient to make that behavior change. So, you can compare different possible sequences and pick a sequence that you think is relatively easy to do, and then analyze each of the actions one by one, looking for the six conditions I'm going to talk about for each action.

* The continuation phase, the idea being that after you finish completing an action, and as time passes, some of the conditions that were previously met might start to fail to be met as time goes on and things change. Those conditions need to continue to be met.

Let's break this down a bit more. In the decision phase, we need three conditions to be met: (1) the person considers changing the behavior, (2) the person desires to change the behavior, and (3) the person intends to change the behavior.

In the second phase, for each of the given actions that make up the behavior, we want the person to (1) remember to take the action, (2) believe that attempting the action will help them reach a goal, (3) choose to take the action, (4) know what it takes to take the action, (5) have the needed resources to take the action, and (6) embody the skills and traits needed to take the action.

Finally, in the continuation phase, the person maintains the attributes required to take future actions.

That's a lot of information. I'm going to break this down even further to determine whether I can use the framework recursively.

Imagine someone named Bob. There are three new behaviors Bob wants to engage in: (1) to become a vegan, (2) to go to a therapist to treat his anxiety, and (3) make sure he takes societal risk into account when he publishes research about viruses, which is what Bob does for a career.

For each of these behaviors, Bob will be likely to succeed if the 10 conditions for change are met.

Let's go through them.

During the decision phase, Bob considers changing the behavior. If he never even considers changing this behavior, it's very unlikely Bob will actually change it. So, what might this look like?

For going vegan, it might look like having a conversation with a friend that gets him to consider it. For going to a therapist for his anxiety, maybe he sees an advertisement for therapy. For taking societal risks into account in Bob's research, maybe he reads an article about the importance of doing that.

Next, Bob must desire to change his behavior.

“Desire” can mean intuiting a positive effect of changing it — a very “System 1” type of desire using [Daniel Kahneman’s framework from Thinking, Fast and Slow, in which System 1 refers to fast, intuitive thinking] — or it could be a more cognitive, “System 2” desire [a more logical, deliberate realization]. It's best if you experience both. But you can imagine that if Bob doesn’t experience either, it's very unlikely for him to engage in these behaviors.

So, how might we help Bob desire these behaviors?

We might appeal to the morality of eating vegan and the potential benefits of going to a therapist for anxiety. [For the third change], maybe appealing to consistency would work; if Bob went into biological research to help people, why would he publish research that might harm people?

Next, we need for Bob to intend to change his behavior.

This means that Bob anticipates doing the behavior at a particular time, or in a particular place, or over a particular period. If you made a bet with Bob, would he bet against or for himself in terms of changing that behavior? We can all relate to that feeling (e.g., "I know I should go to the gym and I want to go to the gym, but I'm not going to do it right now because I'm too busy in life”). You don't actually intend to do the behavior.

For Bob to intend to change these behaviors, we might help him set a frequency intention (“I'm going to do this behavior every day”), a calendar intention (“I'm going to do this behavior at a particular point in time”), or an implementation intention (“Whenever X occurs, I'm going to do this behavior”).

Then, we reach the action phase. Remember, a behavior change usually involves a number of different actions, and for each one, six conditions must be met. First, Bob must remember to take the action.

If he forgets to take the action, it probably won’t occur.

To help him remember, we might create calendar or alarm reminders for Bob's phone, or maybe social reminders — Bob's friends or family could remind him.

Bob must choose to take the action.

This is about choosing to take the action over other opportunities available at that moment. Does Bob do the action or does he play video games instead? If Bob doesn't choose to take the action, he’s probably not going to engage in the behavior. For this, we might do things like remove temptation.

We could put Bob in a place where there aren't video games available at the moment he’s supposed to take the action. Or, we might structure the action around Bob’s procrastination. Maybe he can work on this action when he's avoiding doing his taxes. Or maybe at the moment [where he has a chance to take] the action, Bob can visualize the harm that will occur if he doesn't take the action.

Bob must know how to take the action.

If he doesn’t, he's probably not going to do it.

We could help him memorize what to do, have him conduct his own research on how to do it, or engage him in a discussion about how to do it.

Bob must have the necessary resources to take the action. If he doesn’t, it's going to be really hard for him.

We could help Bob by stockpiling vegan foods in his home. Maybe the government offers free therapy in certain cases. Maybe Bob could get grants for considering the risk of his research.

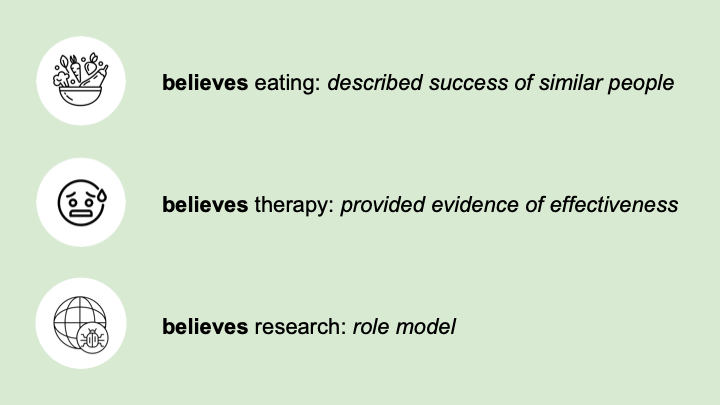

Bob must believe that taking the action will help him achieve his ultimate goals around the behavior. If Bob doesn't have a sense of self-efficacy and thinks that he's not going to be able to succeed at taking the action, or if he doesn't believe that the action will really get him where he's trying to go, then it's unlikely he's going to take the action.

We might, for example, find people similar to Bob who have succeeded at achieving the behavior and describe those people to Bob. Maybe we can provide quantitative evidence showing the effectiveness of taking these actions. Maybe we can provide Bob with a role model to coach him.

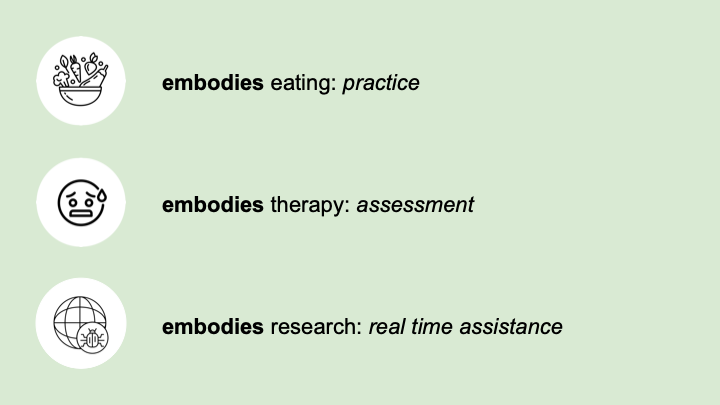

Bob must embody the physical and mental characteristics or skills needed to take the action. Of course, if Bob doesn't have those attributes, it's very unlikely he'll be able to take the action.

We can have Bob practice. We can put Bob through an assessment to make sure that he has the necessary skills. We can give Bob real-time assistance at the moment when he's trying to take the action.

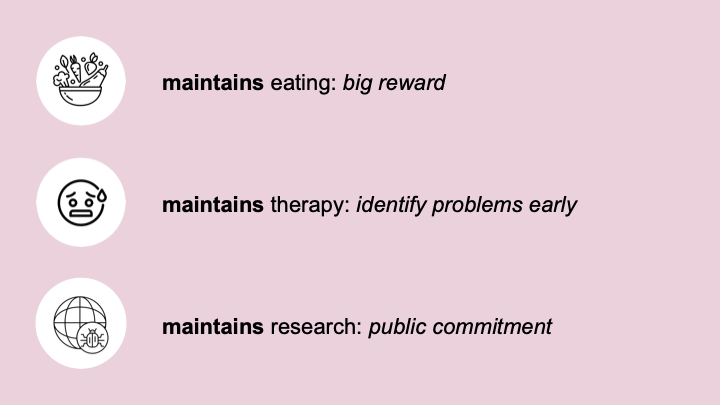

Finally, in the continuation phase, Bob must maintain all of the conditions we talked about. If any of them fall out of place as time passes, or after Bob completes certain actions, then Bob probably cannot ultimately succeed at changing the behavior.

To help him, we can do things like offer a big reward if Bob succeeds, help him identify which variables are [slipping], or have him make a public commitment designed to keep those variables intact over time.

Quick summary: There are three phases.

The decision phase requires that three conditions be met. In the action phase, the behavior is broken into multiple actions, and for each of those actions, six conditions must be met. Finally, there is the continuation phase; if we want the person to continue the behavior, certain conditions must be maintained over time.

I don't expect you to remember all of this. The framework is totally free for you to use.

You can find it at sparkwave.tech/conditions-for-change, a webpage that walks you through these phases in great detail.

One thing that I didn't go into much is that for each of these conditions, there are a number of different strategies you can use. So, if you're thinking about creating a new behavior in your own life or in someone else's life, you can walk through the different conditions, figure out which ones may not be met, and look at the possible strategies you can use (or brainstorm others). That can help you diagnose what's going on.

The other thing I'm excited about is the bottom of the webpage, where we’ve summarized seven other behavior change frameworks. We want you to think about behavior change and doing it more effectively in your work and life. We encourage you to use our framework, but also check out others. They can help you think about how to do it more successfully.

With that, I ask you to go out and make positive behavior change in your own life or the lives of others. The world needs it.

Moderator: Thanks very much, Spencer. My first question is: How did you come to these 10 steps? What was your methodology?

Spencer: Great question. I like to think of what we did as a sufficiency analysis: if A, B, C, and a range of other conditions are all met, here is what will occur. We tried to systematically figure out what A, B, C were — and that’s why we might end up adding more conditions in the future.

We also made a database of over 250 behavior change strategies. So, as we work to link those different strategies to the different conditions we identified, we may eventually see that we're missing something — that there's a strategy that doesn't fit with any of these 10. That will help us identify more conditions.

The basic idea is to try to create as strong a set of sufficient conditions as you can. Of course, I'm not going to say that it’s absolutely guaranteed that someone who changes a behavior will have met all 10. The idea is that it’ll be very likely.

Moderator: Did you test this out on anyone?

Spencer: I've been applying it to different behavior change challenges that I see at Spark Wave. This is a really new model, so it's still early days.

But really, the idea of the model is to use it to systematize your thinking about behavior change and identify what's going wrong. So, you can think of it like this: There are hundreds of possible behavior change strategies and there are several possible behavior change blockers. We want you to be able to systematically think through them to figure out which ones are most appropriate for your challenge.

Moderator: I have a question from the audience focused on helping create change in other people — for example, preventative measures like helping a child eat healthily to prevent issues later on in life. When the positive outcomes come later, how does this framework help?

Spencer: Let's say you're trying to help a child eat more healthfully. You can just go through these 10 conditions and for each of them ask, “Are they met?” Has the child considered eating healthfully — yes or no? You probably will know that. Does the child desire to eat healthfully — yes or no? As you go through the conditions, you will identify several blockers.

Someone was talking to me yesterday about helping their friend create a positive behavior and we were going through this model together. We noticed that about five of these variables were out of whack. They were like, "Wow. Okay. Now we're really clear on why that person is not engaging in the behavior." It doesn't mean you're going to work on all five variables, but you can pinpoint the options with the highest leverage — i.e., where you think that they're going to get the most improvement for the amount of effort.

Moderator: How long have you been working on this project?

Spencer: I've been thinking about behavior change now for quite a long time, because our company, to a large extent, is a behavior change company and we've been developing this database of behavior change techniques. That's where this all began. That was over a year ago.

More recently, we've been trying to systematize the process, look at existing frameworks, and say, "Where do we think we can add value beyond what the existing frameworks do?"

Moderator: Is this intended to be just a resource for people or is there a further aim?

Spencer: It's intended to be a resource so that organizations trying to help the world can use it, and so that people can use it in their own lives. Also, we use it in our own work.

Moderator: Great. A question from the audience: In the chlorine example, are there any obvious failure points using your framework?

Spencer: I haven't applied the framework to that specific example. But if you think about the desire condition, that has to do with education. You need to go and educate people about the benefits of chlorine to hit that desire condition.

The choice condition involves the person getting to the well and seeing the chlorine dispenser. Are they actually going to choose to do it at that moment? That relates to the chlorine dispensers sometimes emptying, which causes people to stop using them (even when they are refilled). By keeping them full all the time, you're helping to promote that choice, so that in that moment they don't look at the dispenser and think, "Ah, it's probably empty. I'm not going to bother checking." So I think if you break it down, you will find that the barriers can be linked to the different conditions [in our model].

Moderator: In terms of businesses, do you see this being applied in exactly the same way, where you have a problem working as a team and you go through certain steps?

Spencer: You mean internally?

Moderator: Yeah.

Spencer: I'm glad you brought that up, because you could think about some behavior change as getting an organization or a government to change its behavior. There are certainly unique dynamics to a group, company, or government. But at the end of the day, it's really people making decisions.

So, you can apply the model at the level of the individual people in the group. You may not know all of those individuals, but you may know characteristics about them. So, if you're trying to create a governmental behavior change, who are the people with power? You can apply this framework to that person (or maybe it’s those three people). Same with a company. Are you analyzing the behavior of managers? You can apply the model to those individual managers.

Moderator: That seems quite labor-intensive — to walk through the model for every single person on the team.

Spencer: No — the idea is not that you have to do it for every single person, necessarily, but for every single *type* of person.

Let's say you have a company and you're trying to change the behavior of all of the managers. You can think of them as a class of people. When you're evaluating the model’s conditions for an individual, you ask a question like “Is this condition met?” or “To what extent is this condition met for this individual?” When you're doing it for a group of people, you ask something like, “What percentage of people will strongly meet this condition — are 90% of people already meeting it, or only 10%?”

Moderator: How successful do you find that these kinds of interventions are? I mean, we probably all wish we went to the gym more and we've tried these various things. What kind of success rate do you see among people who actually try to implement these strategies?

Spencer: That is exactly the point. Behavior change is really hard. So many of us have things we want to do with our behavior that we don't do. It's really, really challenging. That’s why we designed the system. It's usually not enough to just go with your gut and say, "Oh, I'll try this and maybe it will work." We want to provide a way to be really systematic.

I think the reality is you're still going to fail a lot, but we're trying to make you fail significantly less. That's the goal. If the framework works, that's our goal for it.

Moderator: Awesome. Thanks so much, Spencer.