Dear Reader,

I was writing this essay in August/September 2022, and due to a certain level of perfectionist self-sabotage, this essay was “never quite done.” Life moved on, other projects happened, and I never published this response to What We Owe The Future. I have worked on getting past perfectionistic procrastination, and have been doing a lot better on that front, so when I came across this essay in my files today (about nine months later), I decided to publish what I had. Keep in mind, especially in the intro, that this was September 2022.

Intro

The last month has been filled with discussions and debates sparked by the release of What We Owe The Future (WWOTF) by Will MacAskill. As WWOTF was released, people who are not familiar with Effective Altruism (EA) were suddenly inundated with news stories about WWOTF, opinion articles criticizing or advocating for longtermism, and interviews with MacAskill himself. People who consider themselves Effective Altruists (EAs) were very aware, and in some ways startled, with the rapid attention the movement started receiving.

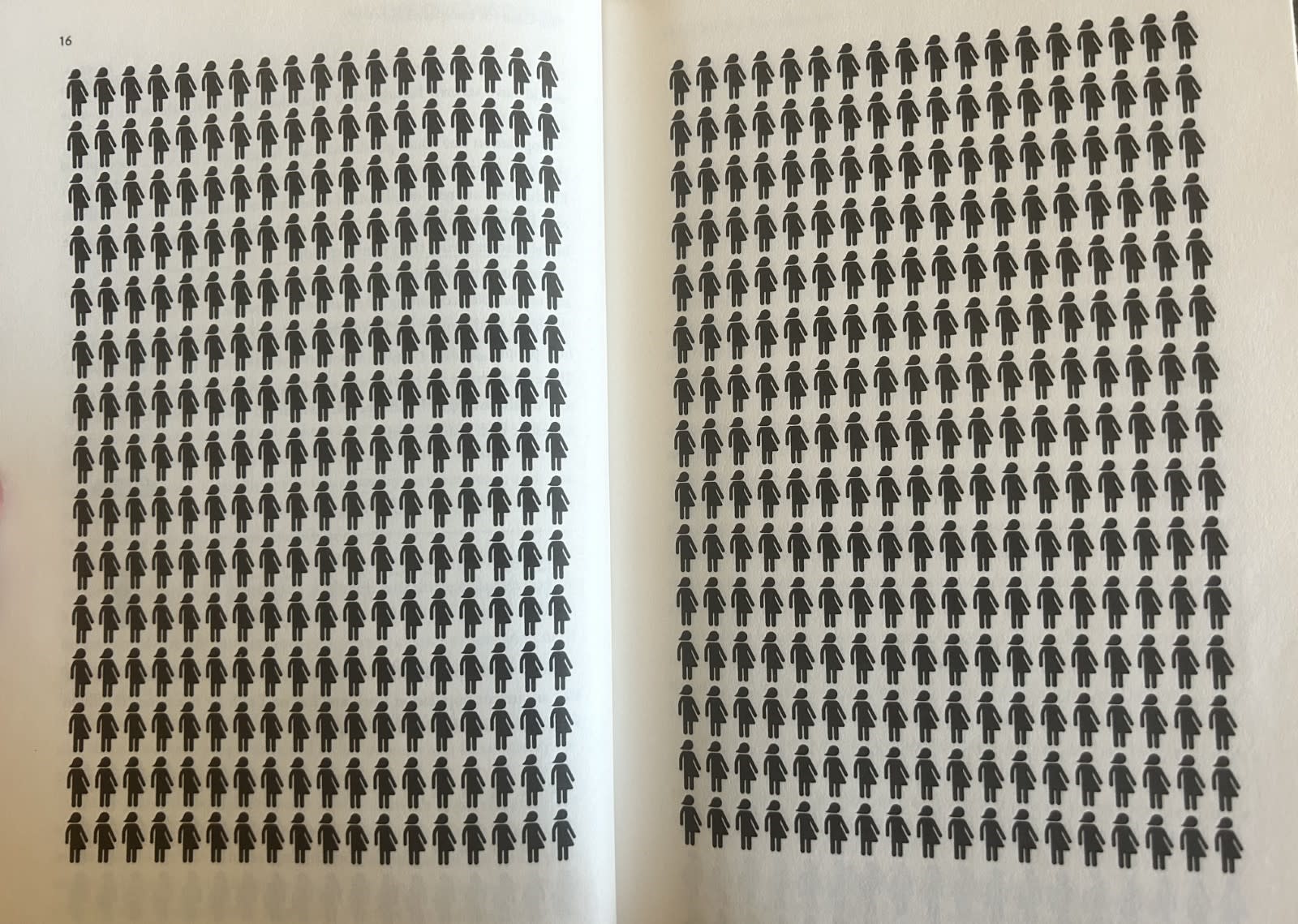

When I read books, I typically prefer getting through them rather quickly (I was that kid who read each Harry Potter book the day it was released and went MIA for a day or so until I was done), but with WWOTF, I decided to slow down and read more mindfully, pausing to reflect on the ideas and how I relate to them. I made it a regular exercise while reading WWOTF to put the book down to do some soul searching and ask myself, “What do I believe?” and other questions to get a clear reading on how I related to the ideas. It was not long after starting the book that I had to stop reading for a few days to do some deep gut-wrenching reflection. Before picking up the book, I considered myself to align with the longtermist line of thought that says, “we should think about how our actions may affect people down the line.” Then came this part of the book where I jokingly made the remark, “Oh what a relief, What We Owe The Future has pictures too.”

(it keeps going, and going, and going...)

I was struck by the description of the potential number of people and how long humanity could last. Before encountering this, I believed that I had the belief in longtermism, but the gravity of some of the possibilities and potential of the future had not fully sunk in before this point. Every so often, I am met with opportunities like this to examine my own stances, and why I might think or feel the way I do. Religious beliefs I used to have paradoxically focused on the longterm future (placing emphasis on eternity, after this life) yet also emphasized the nearterm belief around my generation being present at the end of times (the second-coming of Jesus Christ). Even though I do not have those beliefs anymore, I do not think I allowed myself to deeply stare at the implications of humanity or life just continuing on. I had an emotional response to this, I hypothesize, because where it had seemed a little more abstract in the past, the longterm future felt very tangible, and the stakes even higher.

The Aim of WWOTF

MacAskill writes that his aim in writing WWOTF is “to stimulate further work in this area, not to be definitive in any conclusions about what we should do.” This frame allows the reader to make conclusions on their own, however this framing can also appear confused or indecisive, or that there are big unaddressed elephants in the room (e.g., implications of having children in the timeline where one of the x-risks actually happens). This could be frustrating for readers, as it may feel like there are loose ends, or points being made without connecting the dots to gain the full picture, and potentially some of the x-risks ironically appear neglected or brushed over. However, the way I am interpreting this is that there is a balancing act between trying to steer the future to optimize for survival and goodness, while being cautious not to claim to “know what’s best” for future people. Making claims that are too definitive may result in an unintended value lock-in, so it is understandable that WWOTF is framed as work written “to stimulate further work.”

"But the future is so important that we’ve got to at least try to figure out how to steer it in a positive direction,” MacAskill rallies. The dots aren’t fully connected, but we’ve got to at least try. Fair. How can we do that? WWOTF presents a systematic treatment of how we can positively affect the future, arguing that areas such as moral change, artificial intelligence (alignment and preventing bad actors using AI for control), preventing engineered pandemics, and avoiding technological stagnation are neglected yet important for ensuring the survival of humanity and principles of goodness that can be adaptable to the unknowns of the future.

WWOTF claims that there are two ways that we can impact the longterm future: duration (survival) and civilization's average value (how well or badly life goes for future people– “potentially as long as civilization lasts''). In this post, I will address various concepts in the book, and provide questions and recommendations to both Will MacAskill and the reader of the WWOTF.

Longtermism, Similar Philosophies, and Influences

There was a common critique I noticed from Facebook commenters (who had not read the book) on news stories covering the release of “What We Owe The Future.” Multiple comments said things along the lines of, “Wow, a white male philosopher takes indigenous ideas and calls it something else. How original.”

To be fair to the commenters, there are instances in history when white academics have historically adapted indigenous ideas and created frameworks that get widely disseminated (either not giving proper credit and/or misinterpreting the concepts of Indigenous philosophy. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs comes to mind). An aspect of WWOTF I appreciate is that MacAskill does in fact make an effort to mention cultures and peoples that have or had ideas similar to longtermism (the Iroquois 7th Generation Principle to consider future generations in decision making, and Quakers come to mind).

MacAskill admits that the scope of WWOTF is broad, and while he is making the case for longtermism, he’s also attempting to “work out its implications'' (pg. 7). Moral philosophy is MacAskill’s area of expertise, and experts advised him on the various domains in WWOTF. The acknowledgements section of WWOTF (which includes a long list of names) confirms this.

Why is this time period pivotal?

“Civilization is like this ball: while still in motion, a small push can affect in which direction we roll and where we come to rest” (pg. 28).

This question is the flipside to one of my early whataboutisms with longtermism, which was, “How can I affect the longterm future, when I don’t know what problems they are facing and I don’t know all of the relevant moving parts? Who am I (or who is anyone) to try and decide what is best for the future, when I don’t know what their world is like?” That dynamic made me uncomfortable and reminded me of some of the perpetuated harmful practices in global health such as outsiders deciding what is best for a community without collaborating with the people in the community, like the division of Korea after WWII (pg. 41), or the PlayPump failure mentioned in MacAskill’s other book, Doing Good Better. Then, I realized that while it is valuable to keep this frame in mind, it does not include the full picture. In fact, Longtermism is not an “I know what’s best for the future” philosophy, rather, it is recognizing that the people of the future cannot advocate for themselves, there are potentially a lot of future people, and making decisions without thinking of the longterm future is much closer to not collaborating with a community in a global health setting than my original line of logic in response to longtermism.

Now, I think it is essential to recognize our limitations (the way people 100 years ago would not have anticipated the way in which the internet is woven into our lives), while also taking actions that will likely result in positive outcomes in the future (example given in WWOTF: Benjamin Franklin wanting to have a positive impact and investing £1000 in 1790 to gain the benefits of compound interest, which grew to donations of $2.3 million for Philadelphia and $5 million for Boston dispersed in 1990). In this way, we can attempt to include future people as very real stakeholders in the decisions we make.

Currently we are in an unstable period, according to WWOTF. A time when humanity is more connected than we have been before, and more connected than we will likely be in the future (we are inhabiting one planet currently, afterall). A time when technology and moral values are changing at a faster rate than before, and faster than they will likely change in the future, depending on stagnation and value lock-in.

“...The wildness of longtermism,” MacAskill claims, “comes not from the moral premises that underlie it but from the fact that we live at such an unusual time. We live in an era that involves an extraordinary amount of change” (pg 26). The rate of change, however, is unsustainable which means that we live in a window of opportunity to set the course of civilization to a future that could be vibrant and beautiful, a future that is horrific to experience, or a future where there is no future for humanity and other life. MacAskill likens this period of change or plasticity (before moral values have ossified) to glassblowing. Periods of plasticity are akin to when the glass is hot, malleable, and can be worked into various shapes. Then once the glass has cooled, it is impossible to change due to the rigidity of the glass without remelting.

Basically, the die is not yet cast, the cement has not dried, the writing is not yet set in stone…but one day it might be (especially given the unsustainability of the rate of change). I’m going on three decades of life now, and the amount of change from when I was born to today is a little dizzying when you stare at it. The amount of change that will happen over the next few decades will likely make the last few decades look like amateur-hour in comparison, which I predict will mostly come from advancements in artificial intelligence. It is impossible to anticipate everything that will happen, but we can try to set the future up to have a solid moral foundation, and predict threats and take steps to attempt to mitigate the danger.

The Strategy: Creating Room for Options

Since there is uncertainty about the future, we can try to predict which things could impact humanity’s duration and which things could impact civilization’s average value. Making decisions that conserve options later on for future people making decisions is potentially a good strategy to start with, which can be foundational for ideas such as preventing existential risk, focusing on moral change, and conserving natural resources in the case of a collapse or major catastrophe. Giving humanity options means reducing the ways in which humanity could be foiled. It means reducing the concentration of possible bad, and increasing concentration of possible good. As we do not know with complete certainty how the future will go, we can at least try to shape a trajectory such that people in the future have the resources and options to be able to respond to the changes, dangers, and stressors of their time.

Triage is important too, though. Recently in a conversation I was involved in about longtermism, we discussed the concept of triage in relation to existential threats: the threat of unaligned AI is probably more of an urgent problem to address than the death of our sun, for example. It can be more difficult to prioritize issues that may not have as clear of possible timeline differences, but I wish WWOTF discussed the concept of triage more when it comes to cause prioritization, The book does give a framework for assessing which issues are the most important and will have the greatest longterm impact, which I will discuss in the next section.

A Framework for Longtermism

WWOTF claims there are three major areas to assess when determining the longterm value of an event, which are significance, persistence, and contingency, which forms the SPC framework (created by MacAskill, Aron Vallinder, and Teruji Thomas). This framework can be woven into the ITN Framework (proposed by Holden Karnofsky in order to prioritize global problems), which measures importance, tractability, and neglectedness. According to MacAskill, “Importance” in the ITN Framework could be further broken down into “significance, persistence, and contingency” from the SPC Framework (Appendix 3).

Three major questions are the foundation of the SPC Framework. Significance asks, “What’s the average value added by bringing about a certain state of affairs?” while persistence asks, “How long will this state of affairs last once it has been brought about?” and contingency asks, “If not for the action under consideration, how briefly would the world have been in this state of affairs (if ever)?” Closely related to this framework is the Expected Value Theory, or “thinking in bets” (pg 36), because the SPC framework relies on needing to be able to make decisions about uncertain conditions– the future. Expected Value Theory is based on three principles: thinking in probabilities, assigning values to outcomes, and using the expected value to measure how good or bad a decision is.

On Changing One’s Mind

Will MacAskill did not start out as a longtermist. Like me, he started in more of the global health and poverty side of altruism (note from present day 2023: When I first encountered EA in early 2021, I was in global health, but have transitioned to AI governance). He encountered ideas from longtermism, but found the ideas a little “wacky.” Through talking with X and thinking through the evidence, MacAskill shifted his perspective and became an advocate for longtermism. Later, he goes on to say, “Even over the course of writing this book, I’ve changed my mind on a number of crucial issues. I take historical contingency and especially the contingency of values, much more seriously than I did a few years ago.” MacAskill’s also more worried about technological stagnation impacts, more reassured about the resilience of civilizations in major catastrophes, and more concerned about easily accessible fossil fuel depletion and how that might make it more difficult for civilization to recover after catastrophe (pg. 224).

As I read this account, I couldn’t help but draw connections to The Scout Mindset, and the principle of looking at evidence and updating or changing one’s mind.

It is okay to change one’s mind. In fact, because of the unknowns of the future, important practices to hold onto are having discussions with others, examining evidence, and updating based on the evidence. Yet somehow, we tend to reward those who “stick to their guns” and accuse those who change their minds of “flip-flopping.” There is a difference between the type of flip-flopping that relies on changing one’s mind for the wrong reason (e.g. changing a stance solely to get more votes from a certain demographic in a political race, rather than because there was evidence backing up the stance) and the kind of changing one’s mind that occurs when presented with credible evidence or reason. This is not to discount those who remain committed to ideas and have a track-record of being steadfast and doing good in the world. Just that it is okay to change one’s mind when presented with evidence. I want to take a moment to acknowledge MacAskill and positively reinforce discussing ideas with others, examining evidence, weighing current beliefs with the presented evidence or reason, changing his mind, acting on and advocating for these ideas, and including the process of changing his mind in the text for others to read.

Toward the end of WWOTF, the concept of walking backward into the future is introduced, as there is so much we do not know (what we can see is the past, not the future, so moving forward in life is akin to walking backwards–blind spots and all). The skills of updating in response to evidence and making decisions even when faced with uncertainty will be more crucial as this century continues and the stakes continue to rise.

Questions for Will: I think the probabilities placed on some of the x-risks are lower compared to other people who have weighed in on this (AI x-risk, especially). Do you think that concepts you have changed your mind on recently (the threat of technological stagnation) decrease the level of relative threat in your mind of AI?

The other question that was running through my mind throughout the book is, if the probabilities of the x-risks increase, how does that affect decisions you are making, and how does the morality of certain choices change depending on the level of chance you place on each x-risk?

Questions for Reader: Do a check-in with yourself. What are some ideas you have changed your mind about in your life? What are some beliefs you believe you may believe, but possibly don’t actually believe? Are you open about telling others when you have changed your mind?

Strong Longtermism, Longtermism, and Neartermism, oh my!

Find the “win-win-win-win-wins”(pg. 25).

Recently, I have come across more debate on longtermism versus neartermism online. In order to promote productive discussion, I think it is important to distinguish between longtermism and strong longtermism. This distinction is made in the appendix of WWOTHF, stating,

“This book defends and explores the implications of longtermism, the view that positively influencing the longterm future is one of the key moral priorities of our time. It should be distinguished from strong longtermism, the view that positively influencing the longterm future is the moral priority of our time– more important, right now, than anything else.” (appendices, 2)

In the debates about longtermism and neartermism in regard to cause prioritization, there seems to be an imaginary line drawn where a person or cause is either longtermist or they are not. “It’s better to care for people today, than hypothetical people of the future,” or, “Based on sheer numbers alone, it is better to think about the people in the future.” Life is more nuanced than neartermism or longtermism, and problems are more complex than people of today versus people of the future. In WWOTF, MacAskill claims, “In many cases we don’t draw clear lines between our concerns for the present and the future–both are at play,” and “Just as caring more about our children doesn’t mean ignoring the interests of strangers, caring more about our contemporaries doesn't mean ignoring the interests of our descendants'' (pg 11). An intervention may have a primary intended target audience, but that does not necessarily exclude those outside of the target audience from being affected. Any intervention has stakeholders that need to be considered, and decisions are made, the longtermist would advocate for future people to have a place at the table too, along with those who are alive today. MacAskill gives the example of climate change on how actions now can have an impact in the future, but also how longterm-oriented actions do not need to ignore the needs of people alive now. WWOTF makes the point that moving to cleaner energy is an important step in protecting the future, but it also helps reduce lung cancer, heart disease, and respiratory issues. “We can positively steer the future while improving the present, too” (pg 24).

Interventions targeted at people living today can have a positive impact on the future, and interventions targeted at positively influencing the future can have an impact on people alive today. Many of the existential risks have the potential to happen in the longer-term, but many of them could happen soon.

In doing some digging after finishing WWOTF, I found the post, “Longtermism” by Will MacAskill on EA Forum, which explains some of the confusion and the thought process around the definitions and iterations of “longtermism.” While I know that not everything can make it into the book, acknowledging the distinction between longtermism and strong longtermism in the main text would have been a useful meta-tool for promoting discussion in which everyone is on the same page, rather than potentially talking past each other because of the nuances in these concepts.

Recommendation for Will: Make the distinction between “strong longtermism” and “longtermism” clearer in the text of the book– not everyone who reads the book looks at the notes, afterall.

Recommendation for Reader: Make the distinction in conversations, and be cautious of falling into false dichotomies. Reflect: are there any causes that you consider to be longtermist or neartermist that actually might not be as clear-cut as you think? How might some “longtermist causes” improve the lives of people today? How might some “neartermist causes” improve the lives of future people?

To Whom it May Concern (and this should concern everyone)

In order to have a good future, good things need to happen, and very bad things need to not occur. This is a balancing act, as existential risks pose a threat to our very survival, but moral change in the positive direction is important for ensuring a good future (and preventing a bad one), as a future where humans merely survive is not sufficient.

The visibility of preventing existential risk reminds me of a lecture from the first day of my Intro to Public Health course I took in college. It was 2014, and my professor discussed the way in which public health is a semi-invisible field, saying something like, “A lot of what public health is about is taking preventative action. When these preventative actions are taken, the public doesn’t see what sort of disasters or health crises did not happen. Many don’t realize how much effort is put into making things go right, because those things went right. It’s when something like a pandemic occurs that public health becomes highly visible, because things went wrong.”

There are times in history when this is not the case, and the public is able to see close calls of catastrophe (Cold War era nuclear war close calls come to mind). If each of the existential risks mentioned in WWOTF are prevented (and the other risks beyond those), it’s difficult to say whether humanity as a whole will look back and notice the close calls or factors that could have gone wrong, the way that those working to prevent existential risks think about these issues now. Will people reflect back and say, “Remember when humanity had all those threats facing them like nuclear weapons and bioengineered pandemics? Or how there was that possibility that AI could have ended up unaligned?” If humanity survives, will the threats of old be generally invisible or the very state of existence taken for granted?

Working to prevent existential risk might be thankless (or, it could come down to self-preservation, which I will write more about in the next section). It can be more difficult to nail down the way in which some of the risks are a little more abstract, and therefore the results are less immediately tangible than in other problems. But in a world where things go well, surviving without thanks is worth it. Those who were aware of existential risks and working to mitigate them will probably breathe an exhausted sigh of relief at the close calls.

On Planning for the Future

The ideas within WWOTF have the potential to be quite overwhelming, especially to someone less familiar with longtermism, or someone who is in a major decision-making stage of their life, or perhaps someone is unsure about jumping into longtermism.

My advice if you are dipping your toes into longtermist thinking is to start identifying the “win-win-win-win-wins.” Ask yourself: What are areas I can focus on that have the potential to be beneficial today and are also likely to have a positive impact in the future?

I am in a stage of my life with a high concentration of important decisions that may affect my own life trajectory. WWOTF addresses decisions like career choice and whether to have children. While I found these sections helpful for thinking through those decisions, there was something slightly jarring about focusing on careers and family after discussing multiple ways the future could go badly. I think rather than this being a critique of WWOTF, it is more reflective of the way in which the decisions we make in life are intertwined, and we still have to make comparatively mundane decisions in the face of potential chaos. While we can think in bets, time will pass regardless of our actions or inaction, and the consequences of those decisions will play out.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was still a certain level of mundane keeping-society-functional happening. People still worked, continued with educational pursuits, got married, had children, and so on. The way in which some of these were done were adjusted, but these decisions were still being made in a pandemic. In a similar way, people continue on making decisions about careers and having children while there are some very real existential risks looming. Hopefully some of the decisions we make lessen the risk of those threats, because just as there are possibilities of bad outcomes, there is also the potential for wonderful outcomes, if the threats can be neutralized.

While the issues in WWOTF are mostly framed as protecting the future, many of the problems are concerns that could hurt us in our lifetimes, especially while breakthroughs are happening in life extension technology and artificial intelligence. We don’t know how human life expectancy is going to change and how biotechnology is going to affect that. Those who are cryopreserved may be there for “The Future.” Even without life extension possibilities, a bioengineered pandemic could happen within the next few years. Transformative unaligned AI could happen within the next few decades. While working on the causes in the book has the potential to benefit the future, it does not have to exclusively be for future benefit. It is also possibly for your benefit, and for your family’s benefit, and others in your direct circle. Does that make it slightly less altruistic? Mostly I’d say no, as it seems like a win-win-win-win-win kind of scenario. Self-preservation can be a powerful motivator, and if we have a better chance of survival for threats that could happen in our lifetime, and future people have a better chance of existing, that seems like a win. Regardless of whether these events directly affect us or future people (these are still very connected), the next century is the time for us to take action, while we can.

What We Owe The Future (What I liked, and What I Wanted More Of):

Liked:

- MacAskill’s openness about changing his mind about longtermism

- The explanation of why this time period is pivotal in comparison to past and future

- The pages in the printed copy with the figures of people, and the scale of history/present/future/people

- The explanation of how caring about people in the future doesn’t mean one has to ignore those who are alive now

- The extensive notes and acknowledgements sections

- The emphasis on decision making in uncertainty (thinking in bets, walking backward into the future)

- The discussion on population ethics. It was thought-provoking– though I probably want to read that section again to solidify my understanding of the various stances.

- The word “The” is capitalized in “What We Owe The Future.” To me, it came through as having a certain level of importance or reverence for the future, which was inspiring.

Wanted More of:

- More consistent between the audio version and the printed version (U.S. copy). There were some inconsistencies between the audio version of WWOTF and the written copy especially in the section around contingency, which was not terrible, just slightly disorienting as I was reading the printed version along with the audio version. Mostly I think this was done around areas where there were tables or visuals on the page.

- More of a distinction between longtermism and hard longtermism.

- Discussion about how we (who are currently living) potentially fit into longtermism in a future where we live longer than people currently do, and emphasizing that these issues are likely to affect us as well.

- Discussion on moral decision making around having children in a world where probabilities of existential risk are high.

- Maybe a discussion on intergenerational trauma or epigenetics (though that may have made the book go off the rails, but it would be an interesting connection in how what happens to people now affects people later).