(A theory of meaningful human agency in the age of AI)

The Problem

Several public intellectuals have wondered whether AI will deprive us of the value of human activities we consider “meaningful.” These discussions, which are rarely without controversy, usually occur in the context of “meaningful work”—paid employment that offers us purpose, fulfillment, and stimulation[1]—and are usually connected to the possible shortcomings of universal basic income (UBI) as a policy proposal for combating technological unemployment.

The argument goes that if we’re all laid off from our jobs and given unconditional cash payments every month, then it follows that a major source of meaning for some people will have been categorically eliminated. Nobel-winning economist Daron Acemoglu finds the sense of meaning paid work offers us to be significant; so does economist Daniel Susskind, who has written extensively on the topic, and the philosopher Jonathan Wolff, who uses it as grounds for challenging UBI as a policy proposal. One realizes, without much effort, that a lack of opportunity to embody productive roles in the economy—even in spite of government-granted income—could lead to some people feeling empty and inadequate.[2]

The basic idea—again, that AI will deprive us of the value of activities we consider meaningful—doesn’t necessarily have to be connected to economics, though. Human activities can be paid or unpaid, public or private, and they all stand to be encroached upon by AI. Education, scientific research, art, sports, games, even parenting and caregiving—everything’s on the table. Certain creative endeavors and knowledge work we once prided ourselves on being uniquely capable of doing—the last remnants of human achievement, as predicted by early AI theorists—are now permanently and irreversibly doable by AI. Drudgery wasn’t the full extent of what the latest AI boom automated; far from it.

Here’s a particularly illustrative example: in 2016, South Korean Go world champion Lee Sedol started to shed tears after AlphaGo, an AI system developed by Google’s DeepMind, defeated him 1–4 in a series of matches. In 2024, he stated in a New York Times interview that he was done playing the complex, stimulating game that had been his life’s true calling: “Losing to AI, in a sense, meant my entire world was collapsing…I could no longer enjoy the game. So I retired.”

The Times described Lee’s loss to AlphaGo as “a harbinger of a new, unsettling era.” “Unsettling” may be the operative word here: the transformation of our self-identity thanks to AI achievement has been recognized by several philosophers.[3] AI ethicist Paula Boddington paints a dark hypothetical: “…if a machine can write a love letter to your beloved better than you can, and a robot can fulfill your beloved’s sexual desires better than you can, if the version of War and Peace written and acted by robots is better than the BBC’s adaptation, you might start to wonder why you are alive.” We may not quite be there yet, but there have been troubling developments.

The proliferation of AI art, in particular, has become a lightning rod on social media. Famous creatives, from novelist Stephen King to filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, have strongly resisted it. One can debate whether AI art is worthy of being appreciated, but a fact remains: artists are no longer the only entities in the world capable of creating complex drawings and paintings from scratch. (Photographs displaced certain forms of representational painting and drawing, but these other mediums still provided a stylistic alternative that “realistic” photographs could not offer.) The elevated place of artists in human society, since time immemorial, may have already permanently diminished. With increasing demand for AI content, it’s unclear whether human artists will eventually be rendered analogous to artisans—valued in a sense, no doubt, but only by a relatively small group with expensive taste for the handmade.

Furthermore, can we consistently tell the difference between AI-generated and non-AI-generated art? The evidence suggests the answer is often no. In a much-discussed New Yorker essay, the novelist Vauhini Vara had an AI model generate passages from her unpublished novel, then sent four excerpts—two hers, two AI-generated—to seven readers who knew her work intimately. None of them correctly identified more than half. A fellow novelist who had workshopped with Vara since college misidentified all four. When creative writing students evaluated AI passages imitating 30 authors, they preferred the AI-generated output nearly two-thirds of the time. Scott Alexander, who writes the Substack Astral Codex Ten, discovered similar results when he tested readers on visual art—most were unable to tell the difference.

After taking stock of these examples (and more), criticism of generative AI outputs can sometimes seem like something of a defense mechanism: if you can’t beat it, downplay it. Richly detailed illustrations and animations, which once would have taken weeks, months, or years to make, can now be accomplished in seconds by non-experts. Even if we are reluctant to acknowledge it, this has changed the very fabric of human society; there are vast implications for how we evaluate each other socially and appreciate human talent, skill, and authorship.

These problems are acutely felt in the field of education. AI cheating on assignments has become common, and students can now generate entire essays, research papers, and problem set solutions that they would have otherwise done themselves just a few short years ago. (Academic cheating has always existed, of course, but accessing fully “agentic” cheating—having someone else do all the work for you—has never been easier.) This is a highly problematic change: if students develop their cognitive capacities by actually solving problems themselves, but can easily avoid doing so by using AI, then the entire telos, or “point,” of education seems to be under threat. A student who toils over every sentence of a paper but ultimately ends up with one that is the same quality as their AI-using, cheating classmate’s will face disincentives to go about their work the way they did. Grades and credentials may still exist in 2026, but the hard work that actually builds skills and nourishes minds—and ultimately confers signaling value to these students’ grades and credentials, which are looked at by employers and universities—is about to permanently disappear if something is not done.

Historically, putting a label on what we regarded as “meaningful work” required a common-sense approach, but the distinction between “meaningful” and “not meaningful” has become more difficult to discern and more important to know as AI has proliferated. We must find a way to identify what activities are meaningful; common sense will get harder and harder to apply as this fundamental human driver increasingly rubs up against AI progress. A philosophical approach can provide us with the tools we need.

The Solution

To develop the distinction, this article will rely on the terms “tool AI” and “substitutive AI.” Tool AI will refer to applications of AI that do not undermine human activities central to meaning, dignity, and social recognition. Substitutive AI will refer to the opposite: AI applications that seek to automate and effectively substitute human participation in these same activities.

This dual framework—which I’ll substantiate and develop throughout the remainder of this article—could be applied in a variety of organizational settings, including schools, governments, businesses, and AI firms. Less stringently, it could serve as inspiration for policymakers seeking to regulate AI that erodes meaningful forms of human agency. In any case, the framework identifies the types of human activities which may merit defense from automation.

To get useful shorthand for the types of activities we’re concerned with, we’ll draw upon the concept of “practices” from Alasdair MacIntyre’s book After Virtue, voted the 15th most important work of philosophy of the 20th century by over 400 philosophers.

MacIntyre (2007) describes a practice as a complex, socially established human activity with internal goods (i.e. value to the owner of the activity) and standards of excellence:[4]

By a practice I am going to mean any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative human activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realized in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity, with the result that human powers to achieve excellence, and human conceptions of the ends and goods involved, are systematically extended.[5]

He then goes on to provide a few examples of practices:

Tic-tac-toe is not an example of a practice, nor is throwing a football with skill; but the game of football is, and so is chess. Bricklaying is not a practice; architecture is. Planting turnips is not a practice; farming is.

We might say that tic-tac-toe or planting turnips are tasks, but playing chess and farming are practices.

For the purposes of this framework, the “standards of excellence” are critical. They are the goals that define the practice as a practice in human society; without them, the practice collapses into chaos and becomes unrecognizable. It doesn’t matter whether these standards of excellence are actually met by the practitioner (the person attempting the practice). What matters is that they are striven toward in some way and acknowledged by the practitioner, as they define the practice itself. For example, you have to acknowledge offside as a rule when you play soccer; you have to acknowledge scales when you play or compose Western classical music; you have to acknowledge paragraph structure when you write an essay; you have to acknowledge aesthetic merit (yes, even something that broad) when you create art. Even when you fail to fully meet the standards, they must be reckoned with for you to be acknowledged by an external observer as attempting the practice.

More on standards of excellence from MacIntyre:

Practices of course, as I have just noticed, have a history: games, sciences and arts all have histories. Thus the standards are not themselves immune from criticism, but nonetheless we cannot be initiated into a practice without accepting the authority of the best standards realized so far. If, on starting to listen to music, I do not accept my own incapacity to judge correctly, I will never learn to hear, let alone to appreciate, Bartok’s last quartets. If, on starting to play baseball, I do not accept that others know better than I when to throw a fast ball and when not, I will never learn to appreciate good pitching let alone to pitch.

Striving toward standards of excellence helps the practitioner realize the practice’s “internal goods.” But what are internal goods? They are the specific, intrinsic psychological rewards (kinds of skills, kinds of creativity, kinds of analytical depth, etc.) achieved by actively engaging with a practice and its standards of excellence. In other words, internal goods are the personal psychological benefits gained from the mastery of an activity, with the practice itself serving as the source of those benefits. This does not necessarily mean perfect mastery—it is mastery that corresponds to the practitioner’s level of effort or capabilities.

MacIntyre provides three criteria for these psychological rewards:

- They can only be gained through engagement with the practice (or another similar practice).

- They can only be specified in terms of the practice.

- They can only be recognized by actually participating in the practice.[6]

To zero in on the difference between tool AI and substitutive AI, we must add a new criterion of evaluation to MacIntyre’s practices. We will categorize standards of excellence as either determinate or indeterminate. Determinate standards of excellence are either met (in one specific way) or not met, like a rule; indeterminate standards of excellence have innumerable ways of being met. Our deepened definitions of tool AI and substitutive AI will arise directly from this distinction.

When AI is used to automate engagement with determinate standards of excellence, it is tool AI. Take, for example, automated citation managers and spell checkers: citation managers either format the citations correctly or don’t, and spell checkers either fix spelling to adhere perfectly to dictionary standards or fall short of doing so. It’s an essentially binary matter. (I will note that determinate standards can fall into two categories: a) compliance with socially constructed rules inherent to a practice—i.e. the examples we just gave of citation formatting and spelling, but also rules in sports and games, the scientific method, and so on; or b) instrumental precision in measurement, calculation, or specification—i.e. a tumor either meets the criteria for malignancy or doesn’t; a temperature is either precise to the desired degree or isn’t; a civil engineer’s structural load calculations are either mathematically correct or aren’t.)

When AI is used to automate engagement with indeterminate standards of excellence—strategic effectiveness, rhetorical potency, aesthetic value—it is substitutive AI. For example, there are a myriad of ways to play effectively during a soccer game or compose beautiful music. A midfielder can pass to any of several different teammates and still manage to assist in scoring a goal (to name just one small example); a composer can use any number of different chord progressions in a symphony, and so on and so forth. Likewise, political and military strategists can employ a vast plurality of means and methods in pursuit of tactical success.

When someone chooses between multiple ways of doing something, like above, they exercise practical reasoning. Practical reasoning is goal-directed thinking that determines what to do in a specific situation through evaluating, weighing, and selecting the best course of action.[7] When there’s only one “correct” way of doing something, as in the case of determinate standards, there’s no real practical reasoning going on—the correct way is just the correct way, and it doesn’t need to be sized up, weighed, and appraised.

Within the practice of graphic design, for example, flawless tracing of objects using the “magic wand tool” in Photoshop might serve as a useful example. The magic wand tool either perfectly selects the object the designer wishes to be selected or doesn’t—that’s a determinate standard of excellence, and no practical reasoning was used there. However, the practitioner does use practical reasoning to determine how indeterminate standards of excellence (i.e. artistic and creative excellence, or the appropriateness of the final work in communicating a message to a social group) are ultimately met by using the magic wand tool. In other words, what ultimately matters is what the designer chooses to select using the tool, why they do so, and how it serves their vision. That’s the crucial indeterminate part which we would like to prevent AI from automating.

Finally, this framework only applies to “first drafts” of the practice in question. This eliminates the edge case of a human 1) using AI to generate a “first draft” of the practice and then 2) editing it themselves after the fact. We are trying to ensure that diachronic (“taking place over a period of time”) practical reasoning regarding indeterminate standards of excellence—on the part of a human being— ultimately results in an output that did not exist initially. In other words, we want the human practitioner to be generative, not evaluative. A human can extensively edit an AI-generated draft, but the AI will still have already figured out how to meet the indeterminate standards during the critical initial generative phase. When a human merely looks over and adjusts the AI’s choices, they cannot be regarded as the “first-place” authors of those choices—they are necessarily responding to what they already see.

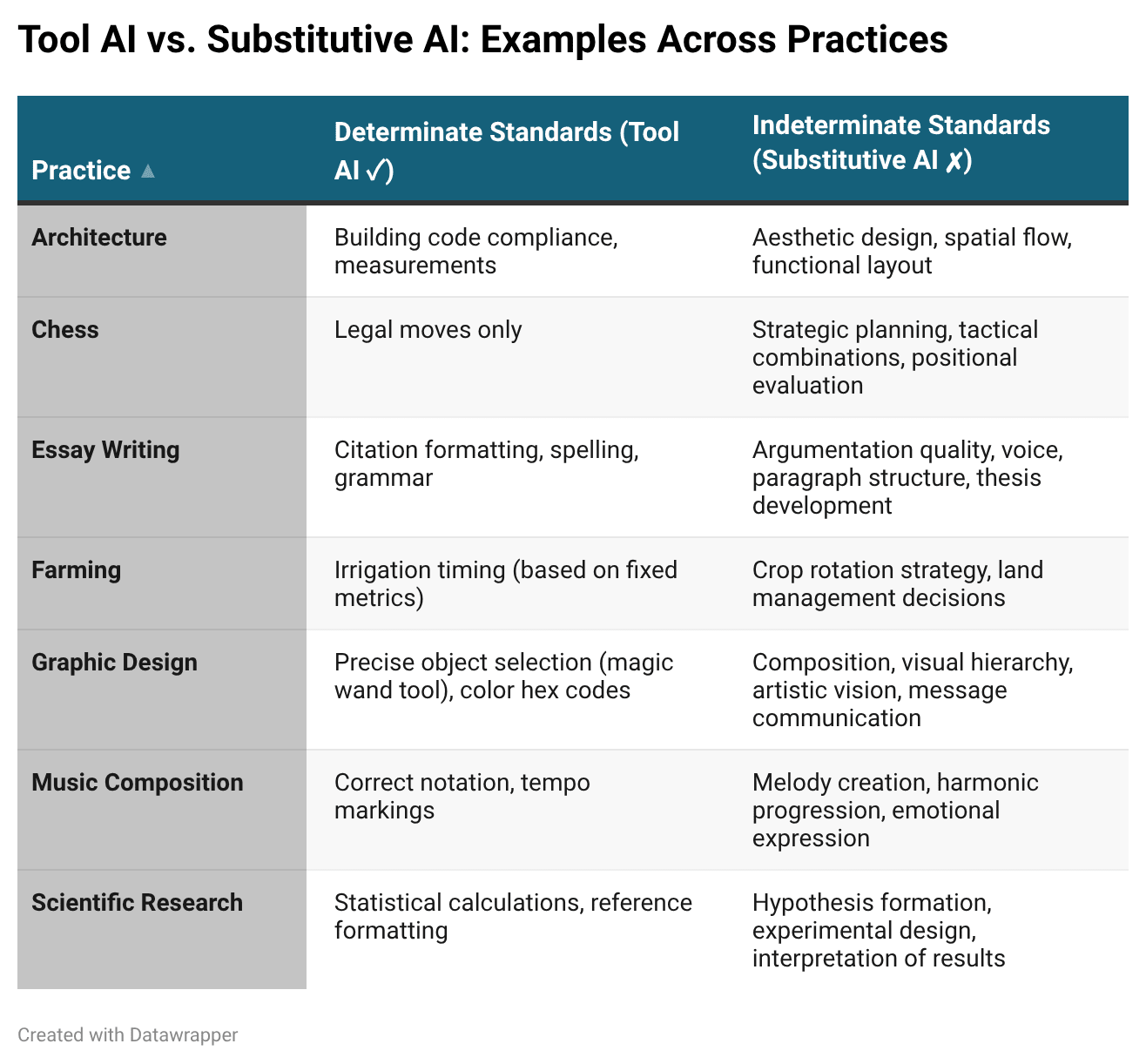

To recap with an example: in essay writing, indeterminate standards of excellence include argumentation quality and voice, among others; determinate standards of excellence include citation formatting and grammar, among others. Tool AI helps with the latter (citation managers and grammar checkers); substitutive AI does the former (writes your argument for you). See the table below for more examples:

The “Hidden-Output Test”

When AI undermines our ability to satisfy a practice’s indeterminate standards of excellence, we lose indispensable opportunities for existential satisfaction and personal growth. If we want to prevent these opportunities from disappearing, we need to highlight and draw attention to whether someone actually grappled with indeterminate standards to begin with.

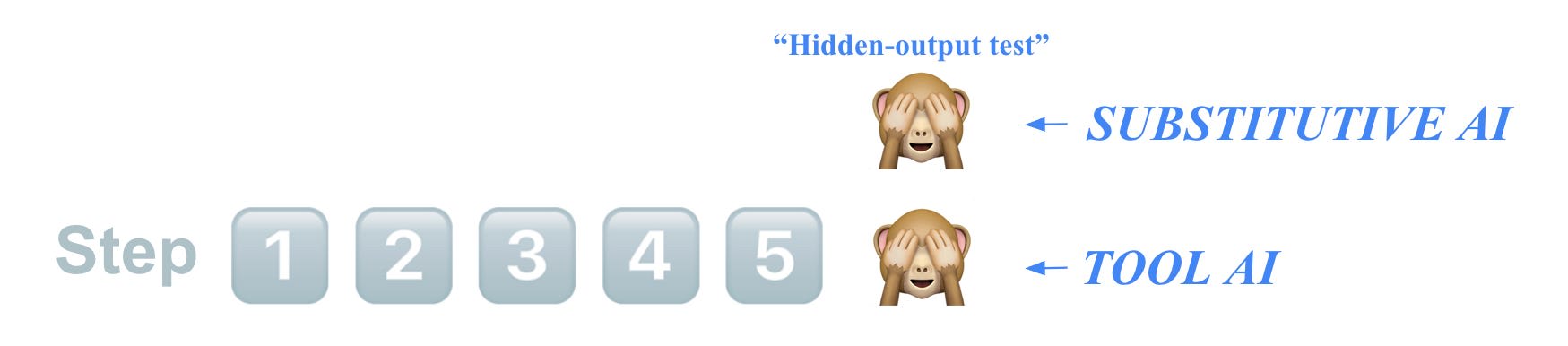

The Hidden-Output Test is a practical way to do this. It’s a thought experiment that stems from a simple question: “Could you explain the decisions you made in your practice if someone hid your final work product (i.e. your output, in a finished state)?”

Let’s take a practice: chess, architecture, farming. All practices have a “finished state” after the practitioner has ended their engagement with the practice—the checkmate, the blueprint, the harvest (respectively for these three examples) and so on. There are many other potential examples.

In the context of the Hidden-Output Test, the finished state of a given practice will be hidden from the human practitioner. (In the thought experiment, this occurs the instant that that output is completed.) Imagine a curtain going in front of a finished painting, or a finished academic paper, or a finished album, or a finished canoe, or a finished baseball game. Behind the curtain, you can’t perceive the output at all. You were supposedly involved in creating it, up to the point when it was finally done, but you can’t see it or hear it or touch it now that it’s done.

Next, you as the human practitioner will be made to answer questions about how specific aspects of the output relate to the indeterminate standards of excellence inherent to the practice you were just involved in.

The questions are all formulated in this format: “What was your thought process in attempting to meet the indeterminate standard of excellence X (regardless of whether you succeeded), and how did that show up in your final output? Please describe in as much detail as you can.”

I’m interviewing you as you sit across the table from me, filling in the blank with a different indeterminate standard each time. I want you to explain to me exactly how you used practical reasoning in striving toward each of the practice’s individual indeterminate standards, and I’m curious about how the choices you made manifested in this unique output, which I’m looking at right now behind the curtain. Since the output is completely unique and I’m asking you to reference specific aspects of it in your answers, you can’t bluff your way through the test with general knowledge of the practice. You have to be able to say how you contributed to the creation of this specific work, using your memory of the steps you took.

Thus, the human practitioner can justify how they attempted to satisfy the practice’s indeterminate standards of excellence—in this specific case—by describing choices that they made within the practice process.

The quality of the responses to the Hidden-Output test form the guardrail surrounding our notion of meaning. If substitutive AI was used, there’s no way for the human to know answers to the interviewer’s questions—the interview subject will draw a blank, since the output was generated instantly with no human practical reasoning regarding the practice’s indeterminate standards.[8] Even if they have some broad idea of what might be behind the curtain through their understanding of how the practice works, the case-specific details will be lacking in accuracy, thereby exposing the use of AI.

A straightforward example: if you had an large language model (LLM) generate an academic paper for you after pasting in a professor’s prompt, and the output was immediately hidden from you, you wouldn’t be able to remember how you used practical reasoning to manifest the practice’s indeterminate standards within specific words, sentences, paragraphs, structural elements, and so on (because you did not). As a result, you would fail to obtain the practice’s intrinsic psychological rewards, and subsequently fail the test.

Another example might involve asking an American football coach how he led his team to victory. He’d have to walk the interviewer through the blow-by-blow of decision-making that led his team to score their first touchdown, along with numerous other “plays” throughout the entire game. If AI did it all, he’d draw a blank and be speechless. He could potentially make things up about certain players doing certain things, but the likelihood that these made-up events and actions would consistently match actual events and actions would be virtually zero, thereby exposing the use of AI. This example, though futuristic and speculative, provides a colorful illustration of the demarcation line for a highly skilled practice.

To be clear, this is just a heuristic, not a rigorous test—e.g. how can you remember every thought you had or every choice you made while engaged in a practice? You can probably remember the most important ones, which will be sufficient. You can use this heuristic as a “quick check” when evaluating how you used AI in the context of a practice.

In sum, the Hidden-Output Test, in spite of its limitations, provides a simple way for you to understand whether you actually gained something by doing something.

Though some readers may find it intuitive at this point, I have yet to explain why “indeterminate standards of excellence” specifically should be our main criterion. Nor have I elaborated on what gives practical reasoning regarding these standards the ability to confer meaning, dignity, and social recognition on people. (In the next post, I’ll explore the why behind this post’s how.)

I’ll also explore answers to the following questions in future installments:

- How can this framework be implemented in real life?

- How do we determine what the standards of excellence are?

- What if satisfying determinate standards of excellence also gives us meaning?

- Aren’t there edge cases, like abstract and avant-garde art? (Hint: practices are socially established by definition.)

- Is editing a practice?

For now, I hope this framework helps guide discussions about AI getting rid of “meaningful work” toward more careful reckonings with what specifically matters most.

If you’re an educator concerned about AI use in classrooms, a parent or guardian concerned about AI use at home, an organizational leader wondering about where human oversight is most important, or simply someone trying to figure out where and when to use AI in everyday life, I hope this article offers a useful jumping-off point for further conversation. AI progress is inevitable, but the way we’ll respond to it—and organize our social world around it—is no foregone conclusion. We have an obligation to deliberate on it together.

- ^

Wolff (2020) notes: “Although many people say that they would prefer not to work, when they are faced with the choice, it seems the great majority of people want to do something they regard as useful and would prefer to work (whether or not it is paid).” There is empirical backing for Wolff’s claim, and it appears that humans do in fact derive value from work even if the need to accumulate wealth is rendered irrelevant. Surveys on the “lottery question”—whether people would stop working in exchange for a large sum of money—have consistently demonstrated that 65 to 93 percent of workers would continue working, even in unindustrialized contexts where an American, Western, Protestant, or Judeo-Protestant work ethic does not prevail (Paulsen 2008, de Voogt and Lang 2017).

Research of the actual behavior of lottery winners suggests most of them continue to work after winning, but this depends on the size of the prize and centrality of work to the winner’s life (Kaplan 1987, Arvey et al. 2004, Hedenus 2012). Moreover, denying prisoners the right to press shirts in a prison laundry, clean latrines in the prison gym, or package computers in a prison workshop has been used as a form of punishment—and this is true even in cases where the work is unpaid or where prisoners have access to other sources of income (Atkinson 2002).

- ^

Several theorists have affirmed the centrality of work: Jean-Philippe Deranty (2015) surveys relevant historical literature to indicate that, under different guises, “the activity of producing goods and services for the needs of others” has been consistently relevant to learning and socialization processes across time and place. Moreover, Deranty (2021) argues that if we assume human society functions as a cooperative scheme to ensure its own reproduction and that of its members, advocating for “post-work” societies would seem to make little sense; should AI manage to overtake virtually all work on the labor market, the activities required to reproduce human society—and all of the individual and collective life within it—must still be completed by humans themselves. As Deranty writes: “Even if new technologies make some forms of human work redundant, human societies will remain work societies, if by work is meant the activities human beings purposely engage in to sustain their own and their peers’ lives, within the frame of collective organisation.”

Paul Gomberg (2007) proposes the concept of “contributive justice” (cf. distributive justice)—justice defined in terms of satisfying what people are expected and able to contribute to society, since what we do for others is at least as important in defining who we are as what we receive from others. Gomberg contends that complex and stimulating work allows people to develop and apply their capacities, while achieving both the internal goods of a practice and external goods of social recognition.

- ^

Notably Gary O’Brien (2025) and Carlo Ludovico Cordasco & Carissa Véliz (2025).

- ^

MacIntyre, A. C. (2007). After virtue: A study in moral theory (3rd ed.). University of Notre Dame Press.

- ^

To be clear, my test inherits any issues in MacIntyre’s framework. Paul Hager (2011) and others have helpfully clarified ambiguous cases, but for our purposes the original definition, taken verbatim from After Virtue, will work just fine.

- ^

MacIntyre contrasts internal goods with external goods (money, fame, etc.); unlike these external goods, internal goods cannot be acquired by other means. There are many ways to become famous, and acting in films is only one of them. The enjoyment of a well-cooked meal is internal to cooking, but the payment received for it is external, and you can receive payment for a large variety of activities anyway.

- ^

This has affinities with the reason-responsive theory of autonomy as proposed by John Martin Fischer & Mark Ravizza (1998), among others; according to these philosophers of action, a self-governing agent does not merely endorse their motives—they implicitly justify their endorsement via practical reason, being capable of responding to a sufficiently broad range of reasons for and against behaving the way they do. Importantly, these philosophers believe that the capacity for self-reflection encompasses more than higher-order attitudes.

- ^

It is worth clarifying that we hide the output so that humans cannot provide a post-hoc (“after the fact”) justification for why the output meets indeterminate standards of excellence, even if it does. Participants must instead refer back to their own mental steps of practical reasoning (or lack thereof).