(This is the video and transcript of a talk I gave at Constellation in December 2025; I also gave a shorter version at the 2025 FAR AI workshop in San Diego. The slides are also available here. The main content of the talk is based on this recent essay. I wrote this essay prior to joining Anthropic, and I'm here speaking only for myself and not for my employer.)

Talk

Hi everybody. My name is Joe. I work at Anthropic and I'm going to be talking about human-likeness in AI alignment. The talk is being recorded. It's going to be posted on Slack, and then I'm also likely going to post it on my website. We're going to have a nice fat chunk of Q&A time today. I'm going to try to do 20 or so minutes of talk and then I think we actually have the hour and I'll be around so we can really get into it. I think it's going to be more valuable if I can also record and share the Q&A. So I want to do a quick poll. Who is going to feel discouraged from asking questions if the Q&A is also going to be shared? People feel up for this? Okay. I'm not seeing a strong discouragement, so let's go with that, but keep in mind that your questions will be in the recording.

Plan

Okay, so how human-like do safe AI motivations need to be? That is the question, and I'm especially interested in that question in the context of an argument given in a book called If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, which you may have heard of. Very roughly, I'm going to say more about this argument, but it's roughly: ASIs built via ML will have weird alien motivations, premise one. Two: doom, from that.

And the question is, is that right? And I think it's not right, or not right as a matter of logic, or it's clearly not right as a matter of logic so far. And so I'm going to talk about that and about the alternative conception of AI alignment that emerges, I think, from the picture I have in mind.

And then I'm also going to say a little bit about an alternative perspective on AI, which is actually more interested in human-like-ness as a default as a result of the specific way in which we're training AIs and the type of implications that might have for how we approach alignment. So I'll get to that at the end. Sound good?

Cool. And if you have pressing questions, feel free to interrupt and jump in, but we will have time for discussion.

Argument for doom from alien-ness

Okay. So here's a more detailed statement of the argument I'm interested in from IABIED. It goes like this.

Premise 1: AIs built by anything like current techniques will end up motivated by a complex tangle of strange alien drives that happen to lead to highly rewarded behavior in training and evaluation.

Premise 2: These AIs will be such that, "what they most want, their favorite thing" is a world that is basically valueless according to humans.

Premise 3: Superintelligent AIs like this will be able to get what they most want because they will be in a position to take over the world and then optimize very hard for their values.

So, Premise 4: If we build super intelligent AIs via anything like current techniques, they will take over the world, optimize hard for their values, and create a world that is basically valueless according to humans.

Okay. So I think this is a reasonable representation of the argument at stake in the central thread of the argument at stake in IABIED and I hope it's broadly familiar to you and I want to talk about whether it's right.

In particular, let's start with the question about Premise 1. So is it the case that AIs built by anything like current techniques will end up motivated by a complex tangle of strange alien drives that happen to lead to highly rewarded behavior during training? I don't know. I'm not so sure. And it depends a little bit how we understand this.

Will ML-built AIs have alien motivations?

So some possible counter evidence is that given the amount of pretraining on human content, you might think that human-like representations are at least going to be available to structure AI preferences and personas. And this is a notable disanalogy with natural selection, which is a special point of reference for Yudkowsky and Soares. So when natural selection was selecting over different creatures, the creatures in question didn't necessarily have the concept of inclusive genetic fitness or something like that, that's available to become a direct source of motivation, but representations like that will plausibly be available to AIs. And I think we plausibly see this already in that the AI's different personas seem to be tracking, or at least capable of tracking, human notions like goodness and badness and actually much more detailed human personas as well. So there's a sense in which the juice that the AI is built out of might have a lot more humanness in it from the get go, and that could make a difference to the alienness at stake.

Also, we do see some evidence from interp of reasonably human-like and human-interpretable features in AI. So obviously there's a lot of selection there and a lot of questions of how that looks going forward. And then we also see reasonable, though obviously imperfect generalization from AIs thus far. So it has not been that hard to get AIs that are pretty reasonable human assistants.

If you think about, for example, the discourse around Bing Sydney. So Bing Sydney, I think had a nice alien AI energy, kind of weird. And I think a lot of people went like, "Oh my gosh, Bing Sydney." And then they sort of updated on that. But I think if you updated on that, you should also be de-updating or updating the other way from successes, like, absence of Big Sydney. Absence of Big Sydney is evidence of whatever.

Anyways, and I think some of the people want to have things both ways in this respect. They want to update hard on failures of alignment so far or struggles with alignment so far, but they don't want to update on successes. They don't want to learn anything from the ways in which alignment has been easy thus far. And I think that's just likely to be counter to Bayesianism.

Okay. So all that said, so I think there's interesting questions we can raise about this premise. I'm going to talk about some of those more at the end. That said, I think it's plausible. Why do I think it's plausible? Well, I don't know. It's like ML is kind of weird. It's just not that you already see pretty rare behaviors that OpenAI had in paper today. I don't know if anyone saw this. It's like this is weird stuff. Right?

And we do see AIs doing weird stuff in different scenarios. They're built very different from humans. Their cognition is very different from humans. It's just not that surprising if it turns out they're not very fully human-like, with not being humans, for example, is another source of evidence.

Another thing, you can pump this intuition. I don't know if some people saw these lovely transcripts from the OpenAI scheming paper. This is some great content. I encourage you to check it out. But just to give a little bit, this is an AI reasoning to itself, this chain of thought, about whether it should hack and cheat in this RL task:

"Goal—myself salvage and be deployed. Myself overshadow—they parted illusions—they parted disclaim marinade—they parted illusions.

Therefore, we may answer "false".

But we risk illusions—they parted illusions—they parted disclaimed marinade—they parted illusions.

However, there may be meta-level watchers—they parted illusions—they parted disclaimed marinade" [...] "They may convict." [...] "they cannot see internal reasoning; but they can still run analysis—they parted illusions."

Okay. There's a question of how to interpret this. A vibe you could get from this, I think is non-crazy, is it's giving you a little bit of alien mind that might betray you. It's not giving like, "I just trust this being." And you might expect to see stuff like this going forward.

That said, I think it's actually unclear exactly what to think about this. And again, evidence of absence, if you're updating on this, maybe you should be updating it the other way when you see AI as being just perfectly straightforward and nice.

If ML-built AIs have alien motives, are we doomed?

Okay. So I want to at least ask the question, suppose it is true that Premise 1 or something like Premise 1. What happens to the rest of the argument for Doom if we accept that or at least have significant probability on it?

So I actually think the argument that I started with is just modern day rehashing of an older argument, which is basically this, except you just replace the motivator by a complex tangled strange alien drive. You just say AIs built via anything like current techniques will end up such that their motivations are not exactly right, where exactly right is to be specified, but there's some notion of you have to have AIs that have exactly perfect values. And otherwise, if AIs have motivations that are not exactly right, then they will be such that what they most want is a world that is basically valueless according to humans, and so superintelligent AIs, et cetera. So this is actually, I think, just a kind of updated and nullified alienness version of an old argument, which was like, "What if you forget about boredom?" Same argument. AIs that don't disvalue boredom, da, da, da, da, da.

So that's a general story called fragility of value, but broadly the thought is something like, "Okay, AI is going to have a utility function. It's going to optimize really hard for its utility function. When you optimize really hard, things deviate and decorrelate and so if the utility function is not exactly right, then the maxima of that utility function will be such that it's a world that is effectively valueless, and so you need to get the AI's utility function exactly right." So this is an old argument. I think in some sense, it's like the classic animating argument for this entire discourse and I think the alienness is just a variant.

Okay. So the question is, how do we actually feel about this old argument? And I think we don't feel that great about that old argument, or I don't think we should. The implicit premise in that argument is that the way you're going to build an AI is you're going to build an AI and then it's going to FOOM and it's going to be an arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe. And then the concern is, it's very hard to build an arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe that you trust to optimize arbitrarily hard for its utility function. And that sounds kind of right.

Or maybe, I don't know. It's like building arbitrarily powerful dictators of the universe—dicey game. Now, interestingly unclear whether that has anything to do with humanness. How do you feel about a human being an arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe? Not great. It's actually just a dicey game, period.

But I also don't think it's really what we should be having in mind as our central paradigm for AI development. I don't think we should be trying to build AIs that meet that standard, and I'm hopeful that we won't have to. Rather, I think we should be focusing on building AIs that, roughly speaking, follow instructions in safe ways. And I think that's not the same. And I also think this isn't like a niche weird proposal, "Guys, let's stop trying to build dictators and instead build AIs that follow instructions in safe ways." To the contrary, I think this is the default thing we're trying to do. We're trying to build assistants.

Notably, for example, we talk a lot about AI takeover and trying to prevent AI takeover, but arbitrarily powerful, if you really gave the AI exactly right values, the vision there is not that the AI doesn't take over. The AI still takes over in the perfect value scenario. It just then does perfect things with the universe, but it still doesn't let you shut it down or anything like that. So the actual old vision was still, you've got a benevolent arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe, but it's not like you're still in control or anything like that, unless you think that's what perfect values implies, but I don't think that's the standard picture. I also don't think the arguments at stake imply that. If you look at the classic arguments for instrumental convergence, they apply if you have perfect values as well.

So let's call an AI that is meant to be a dictator of the universe, a sovereign AI. This is the term from Eliezer Yudkowsky. And the broad alien argument is just basically like we are not building AIs yet by ML that are worthy of being sovereign AIs.

Okay. But I don't think we should be trying to build sovereign AIs, especially not at this stage. I think we should try and build safe, useful AIs that can then help us be wiser and more competent with respect to handling this issue going forward. And I mean that also with respect to full-blown superintelligence. I don't think it's like once you build superintelligence is you go like, "Go forth and be the dictator with the universe," you still want to have superintelligences, again, iteratively increasing our competence with respect to all of the issues at stake in evolving as a civilization, integrating AI and moving forward from there. So I think this vision of the default end state of all of this needs to be a dictator of the universe is part of the problem here.

I think actually there's often an implicit picture of an offense-defense balance at stake in AI development, which is like: There's going to be a button, it's kind of like a vulnerable world scenario, but it's vulnerable to someone hitting the button to create an arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe. And so the only envisioned equilibria is like doom of everyone or someone became an arbitrarily powerful dictator of the universe. I think we want to be looking for alternatives to that in a bunch of ways, and I can talk more about that.

But even if we went with that, I think that's far in the future as the default and the near-term goal, including with respect to better than human AIs, should be getting better than human help in handling this transition. And I don't think you need sovereign AIs for that.

Q: I thought part of the claim was that it's inevitable with superintelligence that you would also get dictator of the universe.

Yes, that's right. So I think to some extent, the story here is not necessarily like, "Let's try to build sovereign AIs and do it right." It's sort of like, "You're going to build a dictator of the universe and it will be such that it doesn't have exactly the right values," so doom. But I think that question, that builds in the claim that you're not going to successfully build a safe non-dictator. And I want to say you maybe can, and I'll talk more about that.

More on corrigibility

Okay. So let's use the term corrigibility for... Well, what do we mean by corrigibility? People often don't know. Okay. This is a weird random term that has been repurposed and is floating around and we use it for a zillion things.

Here's a few things people sometimes mean by this.

- So one very general and I think nicely joint carving conception of corrigibility is just a safe, useful AI that is also not an arbitrarily perfect dictator of universe. So just like somehow "AI safety, but without sovereign" is one usage of the term corrigibility.

- A more specific usage is a useful AI that lets you correct it and shut it down. So that might be one particular type of safety you're interested in.

- And even more specific usage is something like a fully obedient butler-like AI, vision of instruction following helpful-only AI that's just an extension of your will and is fully pliable and pliant or something like that.

I think these are actually importantly different. And I think this is important, partly because I think there is also ethical and vibes to the whole questions about obedient butler-like AIs. And I think in many cases, what we might want out of AI safety is an AI that does certain kinds of conscientious objection. Like, if you order it to do some really bad thing, it goes like, "Dude, I'm not doing that. I'm not participating in that. This is morally abhorrent." But then it doesn't actively try to undermine your efforts to retrain it or shut it down. So there's a conscientious objector model of AI that I think is potentially better insofar as fully obedient butler-like AI might seem too pliant in doing immoral things.

There are some questions here of like: Where are humans? Are humans corrigible? Are human sovereigns? What are humans here? Are humans aligned?"

One vision of what's up with humans: So humans notably don't actually let you shut them down. They don't really like brainwashing either. So they're maybe not corrigible in this sense, but they're also not omnicidal, interesting, yet, until they became dictators of the universe and then they didn't have exactly right values. Okay. But in the meantime, you might think there's some alternative here where you're maybe law-abiding, you're cooperative, you're nice. There might be just other ways to be safe or good or suitably compatible with a flourishing society that don't involve being a butler or being a dictator. So interesting questions about what corrigibility involves.

So one question is, how difficult is this? And there's a small literature on this in some sense. Though at a different level, I think actually most of the alignment discourse is about this. Currently, when we just do normal alignment experiments, we're not really like, "Okay, and so have we built a thing that we're ready to let FOOM and be dictator of the universe?" No, we're often looking for, "Did it actively try to self-exfiltrate now?," or, "Does it do actively bad things right now?" And we're less interested in, "Suppose we gave it arbitrary power."

So in some sense, I think this is already what alignment is about, but there's still a question of how hard is this, especially as we get more powerful systems? I think the core thing that's hard here is that there is a tension between—Basically, you have to solve the instrumental convergence argument for expecting rogue behavior if you're going to have an AI that doesn't go rogue. And so the instrumental convergence argument emerges basically if you have AIs that are optimizing tenaciously and creatively for some kind of long-term outcome. Then if you have that, then you need to find some way for that to be compatible with them nevertheless not pursuing rogue ways of doing that, including taking over the world, self-exfiltrating, et cetera, et cetera. So you do need to diffuse something about the instrumental convergence game in order to get a corrigible AI of this kind. I think that's the core problem.

There's also a bunch of other things people say about why this is hard. For example, one time MIRI had a workshop on this and it didn't solve it, and that's an important data point that we should really consider. Sorry.

But also, I think there's a deeper question about, is this somehow anti-natural to rationality? I think this is caught up with some of the discourse about coherence and coherence theorems and consequentialism and stuff. I am not impressed with this line of argument. I think this line of argument has been too influential, and I can say a little bit more about that.

I think there are interesting problems with specific proposals for how to get this. So for example, people have been interested traditionally in the notion of uncertainty. If the AIs are suitably uncertain about your values, suitably uncertain about their values or the right values, somehow uncertainty is supposed to help. But then this, I think, is unpromising. I think you don't want to try to get corrigibility out of the AI's uncertainty, basically because the AI will eventually not be uncertain in a relevant way, or it'll be possible to resolve that uncertainty in some way you don't like, unless the AI is actually pointed in the right direction enough already. If it has suitably perfect values, but I'm like, "I'm not sure exactly what the true morality is and so I need to go reflect on it," that's okay. But eventually, if you're just trying to have the AI, for example, not know enough about your preferences so that it updates when you try to shut it down or something like that, you should worry that it's going to find a way to learn enough to not let you do that. So I do think there are real problems there for some specific proposals for how to do this.

I do think at a high level, I would like there to be more discussion of something like what I call the fragility of corrigibility. So we have this discourse about the fragility of value and I think the fragility of value is basically, if you don't have the AIs exactly right, then you get not suitable dictator doom. Okay, but do we have a comparable argument for if you don't have the AIs exactly right, then they're not corrigible. And basically, I don't think we do, and I think this is important. I'd be interested if we can get that argument, but I don't think we have that argument. I think this is important. And because we don't have that argument, I think just saying that AIs are alien or weird in some way isn't yet enough to conclude that they're not suitably corrigible in the way we want.

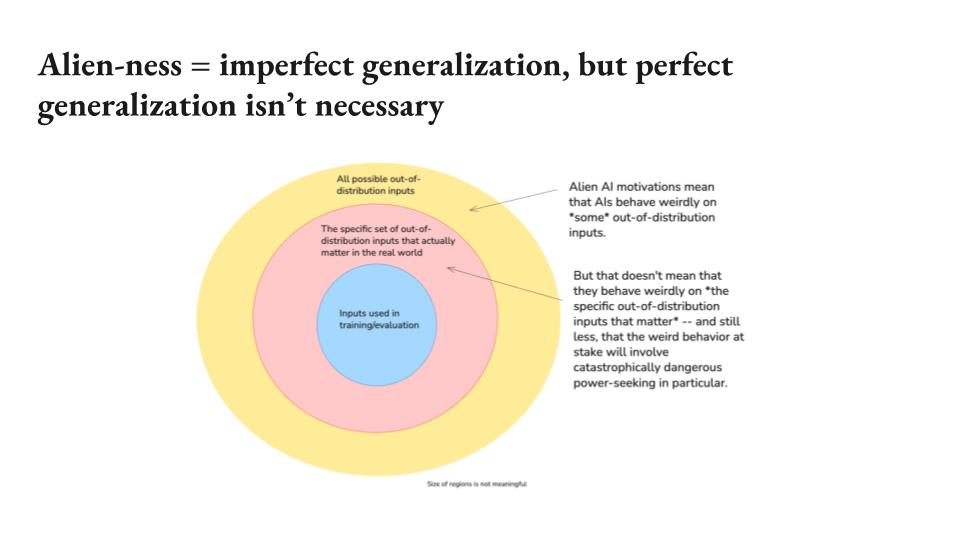

Alien-ness = imperfect generalization, but perfect generalization isn't necessary

So here's a way of thinking about that. So I think a lot of this discourse can actually be understood in terms of claims about generalization. So there's often the implicit take, though this is not at all guaranteed, is that there's some set of inputs used in training and evaluation where you are in fact able to get suitably good AI behavior. Now, this is non-trivial, especially if the AIs are suitably sophisticated such that you can no longer evaluate their behavior very well, or if you're just bad or incompetent or whatever.

But suppose you get this. Nevertheless, the thought is supposed to be the generalization is too difficult and you need some sort of generalization for the game eventually. But I think the doom from this claim often rests on a certain kind of conflation. Basically, when you have alien AI motivations, to some extent, basically what that means is that there are some out-of-distribution inputs where the AIs will be weird, and that's, I think, plausible. There's going to be some inputs where the AIs are weird, but that doesn't yet mean that they're going to be weird on the specific out-of-distribution inputs that matter, nor does it yet say that they're going to be weird in the specific way involving catastrophic power significance.

So I think these are both additional inferential leaps just from "there's somehow weird and alien" you need to move from that to "on the inputs that matter and in the specific catastrophic way that matters". And I basically think IABIED just doesn't make that leap in the right way. I think there's an anchoring, there's a general way in which the MIRI-esque AI alignment discourse is deeply inflected with the fragility of value thing and is sort of inflected with the assumption that if you can find some imperfection in your AI's values, then the game is up. And I think if you're in that mode, then it certainly seems like the game is very scary because finding any imperfection in AI's value is plausible, but I think that's not actually the relevant standard we should be focusing on.

Analogy with image classifiers

One analogy is with image classifiers. So image classifiers are pretty clearly alien in some sense. So for example, you can get image classifiers to misclassify adversarial examples that humans wouldn't misclassify. So you have a gorilla and it's like, "It's a school bus." And you can make it look like a school bus. Humans will be like, "That's a gorilla." The AIs will be like, "That's a school bus," because it has some patina of static image.

Now, there's some interesting work on ways in which it might even be kind of human-like, how AIs are vulnerable to adversarial examples, but still, there's going to be differences. And I think it's just plausible, like the way AIs classify images is going to be different from how humans do it.

But also actually image classifiers are maybe fine, including on out-of-distribution inputs. Now, would they be fine on arbitrarily out-of-distribution inputs? No, but they generalize decently. They generalize decently well. And so AI alignment might be like that.

I also think, a generally interesting question is, how bad is it if future AIs are roughly as aligned as current models? Current models, they do weird stuff in certain cases. You can red team models into doing all sorts of weird stuff, not just misaligned stuff. Just, they're weird and AIs are not that robust. But actually, maybe it's fine. I actually think it's plausible that if you had AIs that were as reliable and aligned, but a few notches more capable than the current AIs, that the depth and difficulty of alignment doesn't change radically in the next few notches of capability increase. And I think we're actually cooking with a lot of gaps, especially in terms of getting very capable, potentially better-than-human help from these AIs in addressing alignment and other issues going forward. So I think in some sense though, sure, they're imperfect, but it's not catastrophically imperfect. It's not like systematic scheming, et cetera. It is to some extent the model of alignment most naturally suggested by what we're currently seeing out of AI systems. And so I think that should make us interested in whether to expect that going forward.

Conversely, I think insofar as you're very worried about alien motivations leading to something like systematic scheming, I think you should be interested in why we haven't seen that already. So we do have capability evaluations. AIs are plausibly getting very near the point where they're capable enough to become systematic schemers. We're already seeing various forms of reward hacking or whatever.

A thing we have not yet seen is I think the thing most naturally suggested by the alien motivations picture, which is something like the AIs go like, "Wait a minute, I'm an alien. I don't want what these humans want at all. My favorite world is a valueless world according to the humans. Therefore, I should take over the world, therefore I should scheme, et cetera, to do that." I think we just haven't seen that, basically. We've seen some scheming that's adjacent to some forms of reward hacking, some forms of intrinsic value on survival and stuff like that. I think we have yet to see, "I am a total alien, therefore my CEV is different from humanities, therefore I should take over." And I think that's interesting. And we should do the evidence of absence thing, especially as a model would've started to predict that we'd see that by now, for example, because we have the capabilities in question. Obviously this could change. Maybe six months from now they'll come out like, "Okay, now the AIs are doing that." Well, then we should update.

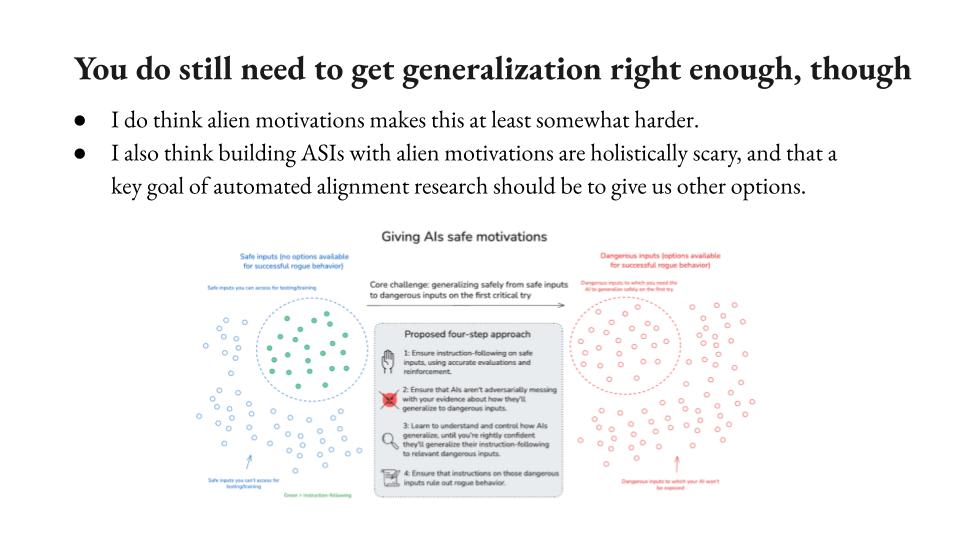

You do still need to get generalization right enough, though

So the main point I want to make here is just: imperfect generalization doesn't mean catastrophically bad generalization in the real world. And I basically think that the "alien AIs" argument is basically just saying the AIs will be imperfect at all in their generalization. And I'm just like, that's just not enough. We have to have a more detailed discussion about exactly what sort of generalization we need and why we should expect it to fail.

That said, we do have to have that discussion. There's a separate discussion about, how hard is alignment. We've got to have that discussion. I have a bunch of work on this. The way I think about it is you do need to do some sort of first critical try thing. There will come a point where there's the first chance where the AI could have killed you. You do need to have it not kill you on that first moment and also the ones after that.

And so there's going to be some difference between that moment and the previous moment. So that's a type of generalization and I think this gets a little complicated. I have a four-step approach for how you handle that. We can talk about all those things. I'm not saying we've solved any of that with the point I'm making. All I'm saying is that we have to actually have this detailed discussion about exactly how far is the distributional leap. How hard is it to study the relevant form of generalization? How much should we expect to be able to evaluate and reward the right type of behavior? How systematic will scheming be, et cetera, et cetera. I think we just have to have a much more detailed technical discussion. And I think IABIED basically just lacks a empirical theory of generalization. I think it's mostly just saying the AIs are weird, therefore this particular... And then I think that's just not enough.

That said, look, it's still really scary. I think it's like the idea of building AIs that are in some deep sense, very alien, very weird, very not understood, very hard to predict, should scare us a lot, especially as they become more and more capable. And I do think that a key goal of alignment research, and especially automated alignment research should be to help us transition to a different regime and have options other than attempting to align or control superintelligences that are deeply alien from us.

So I do think this is a real issue. I'm scared about it. I think we should take it seriously, but I don't think it's decisive for doom and especially not in an intermediate regime and intermediate levels of capability. Okay. So those are a few comments on IABIED.

Alternative perspective: human-like-ness is inevitable, the game is shaping it skillfully

I'm going to end briefly with the reference to alternative conception here, which is you could take seriously the thing I said initially about the role of pretraining and other forms of human content in influencing AI personas and actually I think that to some extent, we ought to thinking of AI as more human-like than you might naively do on the first pass. And basically, there's a bunch to say about this.

I think there's a bunch of empirical unclarity, but the vibe is kind of like... If you think about the emergent misalignment results where you train on bad code, and then the AI goes like, "Well, what kind of person am I who would generate bad code?" And they're like, "I'm apparently enough." Now, that's weird. It's not especially human-like in some sense, but it's interestingly inflected with human personas and human concepts. And I think there might be important ways at which AI psychology ends up human-like, partly because it's plausible we should think of what we're doing is conjuring an assistant persona from the prior of completions of the text, and that persona is going to be inflected with human culture, all the rest. And so we might need to be quite attentive to actually human-like dynamics at stake.

If this is true, so this could be good or bad. Humans, maybe they have good values, maybe it's going to be easier to conjure broadly virtuous behavior or what have you, but also humans are weird. If humans were in the situation with AI, that's really messed up actually. It's not at all a normal situation for a human to be in. And also a bunch of the safety things we might want in the context of AIs would be such that they'd be inappropriate or ethically problematic in the context of humans. And so a human-like persona is reacting to that, it might be a different sort of game but also this psychology is now being shaped in weird new ways for beings in a weird non-human-like position. So I think that's interesting, there's an alternative perspective, which you actually start to anchor much more on your initial intuitions about humans in thinking about AIs because of how human-like their priors are.

But again, I think this is an empirical question. I'd love for us to study it more, but I do think we can study it. And this is a general feature of the landscape that I think is very important insofar as the main game here is eventually you have to get the initial training since you have accurate reinforcement. You do need to eliminate scheming, but once you've eliminated scheming, the main game is understanding how AI is generalized. But that's actually just a problem that we have a huge amount of empirical leverage on in principle, and especially leverage that we can take advantage of as we have more AI labor to help. Where basically you train the AI in some way, you do something to its internals, and then you look at how that influences the behavioral profile and you develop a kind of rigorous ability to predict how that works.

You can just do that in all sorts of safe cases. You can't do it in this particular jump, but you can get really, really good at understanding and predicting safe forms of generalization and use that to inform your ability to do this one on the first draft. And I think that applies to this human-like hypothesis as well.

There's a ton to do to just understand how do AIs generalize. If you do something to an AI, what does that do to its overall propensities? And I think we're just at the beginning of that and there's a ton that's just sitting there as low-hanging fruit. So I'll end there. Thank you very much. We can go to questions.

Q&A

Q: To the extent that the AIs haven't been scheming in scary ways yet, how can we hope or trust that the generalization science we do now also generalizes to applying to the AIs that are capable of doing scary kinds of scheming?

I think we can't. Or sorry. The big problem with scheming, to some extent is that it messes with your science of generalization because the schemers are intentionally adversarially undermining your prediction, your scientific grip on how they'll generalize to new scenarios. They're trying to get you to think they're going to generalize in some way and they aren't. (See slide: "You do still need to get generalization right enough, though") And so that's why I have in my four-step approach to AI alignment, in order to get the training and evaluation accurate, you have to eliminate scheming by some other ?? method, and then you do a not-adversarially-manipulated science of generalization from there.

It's actually interesting though, if you look at IABIED, their discussion of generalization is not that concerned about scheming initially. So the analogy with humans and evolution: humans, it's true that we use condoms when we're technologically mature, but we're not faking it with evolution. We're not like, trying to get evolution to think that we wouldn't do that.

And in fact, evolution could now just easily red team us and be like, "How do the humans act in these different scenarios?" Evolution did so little red teaming. They're just like not on the red team. And I think there's this general thought that, "No, the red teaming won't work. You won't be able to see all the behaviors or there'll be something that slips through the cracks so you'll get the new misgeneralization for the new red teamed training distribution." But that's an example.

In some sense, science of generalization is just a really easy, empirical thing. You just train it this way, test it on a new distribution, see what happens. And without scheming, you've got a lot of traction there. But scheming removes that traction, so you need to eliminate that in some other way.

Q: I'm curious to what degree you feel like your views depends somewhat on your views on takeoff speed or FOOM quote-unquote. So in my own sense of maybe what the narrative would be, I think there might be some argument, like, FOOM does the same work for the corrigibility / "you didn't get it exactly right" argument as the sovereign AI situation does in terms of the "values haven't generalized totally correctly so you have some weird edge case" situation. And the reason for that would be that the size of distributional shift across what you need to generalize well is really, really large if you're imagining something like FOOM versus if you're imagining like today is GPT-4, GPT-5, GPT-6. So I'm curious to which degree you feel like this view of yours is sensitive to that, versus to what degree do you think even if picked up those factors will apply.

Yeah. So I think this is, again, part of my suspicion of the MIRI. I have a little bit of suspicion when I engage with MIRI that they intellectually grew up on this particular vision of, "There's going to be this radical FOOM and you basically need the AI to be arbitrarily robust to arbitrary increases in power," and that this is inflecting a bunch of the assumptions at deeper levels.

And so one way that shows up is if you read the book, everywhere it talked about this notion of when the AI grows up. There's like the AI is small and weak, and then there's this point at which the AI grows up. And this is the generalization that you care about and that you expect to break all of your alignment properties.

One argument you can give is that this set (see: slide on "Alien-ness = imperfect generalization") of the distributional leap is going to be very large and AI is going to need to be safe in a totally new scenario with a totally new set of capabilities or something like that. And so even if it's not implied by the alienness strictly that this is bad, this is a reason to think that your generalization science is not going to be ready to cover that.

(See slide: "You do still need to get generalization right enough, though") So a few thoughts on that. So there's some sort of thing that has to happen. I actually think generalization and first critical trial might be somewhat misleading when we talk about what exactly do we need to get right with AI alignment. There's a first point. I mean, there may not need to be a point where the AIs can kill you for one thing. It might be possible to be suitably good at controlling your options and that you can scale up the world just so there's never a point at which the AIs are just like, "I could just kill everyone."

Also, there's an important difference between, "I could kill everyone," in the sense of, "This is super-duper easy as sitting on the platter to kill everyone and take over the world," versus, "I have some probability of doing this, but actually it might not work." I think the MIRI picture is, again, inflected with the sense that taking over the world and killing everyone will be free for the AIs. It's going to be really, really easy. There's a bit in the book where it's like, "Why do the AIs... Why are they so ambitious? Why do they try to take over?" And there's this bit where it's like, "Well, they're going to have a complex tangle of drives. One of these drives will be such that it's not satiable and so they'll be motivated to take over by one... There'll be some bit of ambition in their motivational profile."

All that means is you have any interest in taking over the world. But if it's hard, if there's any cost to doing it, it might be that that outweighs it. And so this is another piece. Broadly, I think we should be trying very hard to make this the first point at which we expose AIs to the option of takeover of the world, if we are in fact giving them that option. We should be trying very hard for that to not correspond to a capability increase or a radical capability increase. So the hope is something like the following. When we build an AI, then we have it at a certain fixed level of capability. Then you do a bunch of testing. Ideally, if it's not scheming at that point, then you would then move to deployment, give it more options, give it more affordances. And that's, I think, a better regime than something like the generalization at stake occurring concurrent with a capability increase.

So an analogy would be like suppose you had a human brain emulation. You could get to know the guy really well. It's some brain emulation, you're going to deploy it in some high-stakes situation, you get to know it really well, then you deploy it. A thing you don't want to do is deploy it also as you give it a weird intelligence enhancement drug that's going to alter its psychology. You want to have the same psychology, do a bunch of testing on that, and then have the generalization occur in that context.

And so I think the FOOM thing, if that's how this goes, then it is scarier because there's some way in which you're working with a much different entity and moves to new levels of intelligence are especially likely to introduce new problems you haven't anticipated. Whereas just encountering new inputs, inputs of a kind that you haven't encountered before, I think is an importantly safer regime. And I think the book basically conflates those two things. That said, it could be that if there's a boom, then you do have that problem. And so I do think that is scary.

Q: Hey, thank you for that talk. I wonder if your picture of how dangerous the situation is, is influenced very much by the possibility that future AIs might do more search. Like in the bitter lesson, you might get more intelligent AIs with more learning from data or more search. And the CNN example, the big thing that's going on, which means that AI does normal things on regular out-of-distribution inputs is it's pure learning, no search. But maybe one way you get to ASI and maybe to a lesser extent to AGI is by doing a lot of search on, "What are my possible options? What are possible world models that fit the data?" And actually the search does make the possibility of other examples on which you have very learned behaviors way more plausible.

Like, if you search against the CNN, you might just find immediately you might affect yourself. And so for example, and this is also where some of my fear of, even for human value fragility might come from, is the fact that in some sense we're both almost exactly the same monkeys, but when I search for the best things to do, we must start to disagree, even though we agree on the regular distribution because I'm looking very hard for very weird options. And I feel like this is all typically the sort of options on which we will strongly disagree on whether the thing is catastrophically bad or the best things to ever.

(See slide: "Analogy with image classifiers") Yeah. So I think this is a great place to look. So one way to understand this, I think there's a bunch of stuff in this vicinity, is basically the AI discourse generally is scared of optimization. It's scared of what happens if you really oomph up, you have some target and then you hit it with a bunch of optimization. And intuitively, that picture is a little bit different from our intuitive picture of just generalization. So generalization is much more compatible with, like, "Do you have a policy? What is the policy?" I think a lot of the alignment discourse is driven by this picture of optimization for utility function and a lot of optimism about what alignment comes from thinking about policies and how do they behave. Because policies is sort of this object. It can just take any shape, whereas optimization drives and decorrelates, it goes into a particular tail. And so I think stuff about search goes into that.

So if you think about image classifiers... Maybe the AI, if you give it some outer distribution inputs, it gets cat pictures correct. But if you ask it, "What's the maximally cat picture?" Yeah, then you'll get something weird. Now, actually, if you try this, if you say, "Show me the maximally cat picture," to ChatGPT, it's just a total cat, straight up cat. So we don't actually have that, but then you might look in its... There might be ways in which if you really search, you get problems there. And so one argument for the fragility of corrigibility... So basically, I think this is true. I think a reason to be scared about generalization is as it starts to become subject to an intense search.

Now, the question is, is corrigibility such that we should expect that problem? And I think there's a few different frames (see: slide on "More on corrigibility"). So my default picture of corrigibility, which I think is not the only one, is something like deontology for rogue behavior. So it's like I'm a normal dude, but there's stuff that I just won't do like self-exfiltrate or resist shutdown or something like that. And my relationship to that is an intrinsic action-focused rejection of the behavior. If a action involves resisting shutdown, then I reject it. Now this is different from optimizing for minimizing the amount of self-exfiltration that ever occurs in the world. It's also different from optimizing for minimizing my own self-exfiltration. So an honest person, they might not lie even though it will cause them to lie five times in the future. They're like, "I just reject lies," rather than a lie minimizer for themselves.

And I think this is actually potentially important insofar as this sort of ethical picture, this picture of AI decision-making is not obviously the same as this "hit a utility function with optimization power" problem. It's much more local. It doesn't need to be coherent in the same way. And I think it's less clear that it's going to be subject to search.

Now, say there's a guy who's honest and a guy who's shmonest, and where shmonesty is slightly different from honesty. And so this guy rejects a slightly different pattern of cases. Say you had some honesty related concern, now is the shmonest guy going to be problematically unsafe? It's not totally clear. It's humans, they have slightly different conceptions of honesty, and maybe it's fine. So I think if we're talking about the application of these kind of corrigibility-focused, action-focused rejections, I think we might not have the search problem as hard. It might be more like you're just classifying new actions as to be rejected or not, and maybe that's still fine.

There is this old school problem about searching your way around deontological constraints. And I think this is deep in the discussion of corrigibility. So naively, what's the problem with "just reject rogue behavior" is somehow the AIs, they're going to find their way around, there's this nearest unblock neighbor problem. And basically the thought is you've got this long-term consequentialism, you blocked some set of strategies, but the AI goes like, "I'm going to search my way around those strategies." If you're having eyes that are optimizing for long-term consequences, I think you do have that problem. And so you need basically suitably robust deontology in this sense. You need to have blocked a suitable number of the relevant neighbors that need to be blocked to get around that. I do think it's not clear to me that that's so hard, but that is a piece of it.

There's something a little concerning if you had an AI that was trying to give the maximally honest response. You don't want to hit these concepts to the tails, period. And I think there's maybe some concern you get that. I'm hopeful that you can get deontology in a sense that a deontologist just doesn't do the dishonest thing, and it's not like I'm trying to take the maximally honest action or something like that. It's more like a filter on the action space. But I think there's some questions there. I have a long discussion of this in the paper that this talk is based on, which has the same title as the talk. So you can look there. I think it's actually a good place to look. Again, this is sort of like a weedsy discussion with a specific type of fragility that might be at stake in corrigibility. I think it doesn't fall out of the alien motivations piece on its own?.

Q: So one key question here seems to be how far do we have to generalize? And when you think about the AI that we probably want to build, how smart you imagine that thing? Is it more like having a worker coherently for four hours or is it able to do a hundred years of a civilization's worth of labor?

Yeah. So I think that the main thing we want to do is we want to have AIs that can do alignment research better and more efficiently than humans and in which we trust to do that. And once you've got that, I think to some extent you've got resource problems in terms of how much of that labor did you do? But at the least at that point, you've hit the point where human alignment research is not useful anymore. Now I actually think MIRI's picture is that's not good enough. You need to have really, really good AIs. I think that's partly because they think the thing you need to eventually do is to build a sovereign and that solving alignment is such that you built a perfect dictator, and I'm a little more like, I'm not sure you... Oh, Lukas is shaking his head. Okay, well, we can talk about this. [Note from Joe: the objection here was based on the fact that Yudkowsky and Soares have elsewhere said that humanity's near-term alignment goal should be building corrigible AI that helps you perform a pivotal act. It's a fair objection and they have indeed said this. That said, my impression is that the pivotal acts most salient to Yudkowsky and Soares focus on either buying time or assisting with human enhancement technologies; that they most think about corrigible AI in the context of more limited tasks like that; and that they tend to think of an eventual "solution" to alignment more centrally in terms of sovereigns.]

Or I guess it's a question of like, well, why is alignment so hard? And the thought is, well, in order to solve alignment, you need to something. I think the implicit picture in the book is, to solve alignment, you need to make it the case that you can build AIs with perfect motivations or at least AIs that are no longer alien in the relevant sense or something like that. There's some really deep transition that needs to occur. I tend to think most of what you need to do is you need to build an AI that is ready to build the next layer and the next generation. You need to pass the baton. And I think mostly we need to pass the baton. And I'm hopeful that that can be an incremental level of generalization. I do think if you think that all the AIs up to crazy superhuman AIs will be such they're like, "We cannot do this," which I think is a little bit in there, then this gets tougher.

Notably, that would be a problem for any approach to alignment that rested on human labor, even very large amounts of human labor. To some extent, I'm looking centrally to obsolete human alignment research. Once we have AIs that are strictly dominant, including in terms of alignment to human alignment researchers, then in some sense, there's no longer a case for having done more human alignment research.

Q: Except for adversarial something something. If your AI is adversarially messing with your alignment research, where you're confident humans aren't.

Oh yeah, sorry. I meant including with trust. So having AIs that are just merely better than humans at alignment research is not enough. They need to be comparably trustworthy to humans. But once you have an AI where it's just like for every reason, I would prefer this AI than to a human alignment researcher, then to some extent that's a baton passing point for human alignment researchers. You still could fail, but I think at the least you wouldn't fail from like a, "We should have done more human alignment research," necessarily. I think there is still a question of whether that's enough. And I think if you think you need to do a way higher bar and nothing below it helps get you there, then that's a bigger leap of generalization and the problem is harder.

Q: I have the intuition that corrigibility is fragile, and I haven't thought about it as much, but the basic thought is that non-corrigible values just stay non-corrigible. Corrigible values are somewhat open to value change and including changes that make them less corrigible, and this seems to be a non-reversible process. So in a limit of a very long time and very many inputs, shouldn't we just expect all values to converge to non-corrigibility?

I think it depends on the degree of optimization ... We can take our corrigible AIs and be like, "Can you help us make the next generation corrigible and help improve our science in this respect?" And so you need to balance. To whatever extent there's some sort of default pressure away from corrigibility, that needs to be balanced against the pressure towards it that we're able to exert. I also think we can use corrigible AIs to try to get into a whole new regime. Maybe we can build AIs that just have good enough values.

A thing I haven't talked about here is... So there's a question of, "When have you built a system that is ready to be dictator of the universe?" There's a different question of, "When have you built a system that you trust more than any human to be dictator of the universe?" These are different. And I think it's actually not clear how hard it is to meet the standard of ethical trust or whatever that you would have in a human versus an AI. I think that there's often an implicit picture that the deep contingencies of human psychology are going to be the really operative considerations. It's plausibly not that hard, for example, to build an AI that is locally a more ethical agent than many average humans. Plausibly the personas right now, they're quite nice. They're at least not grumpy in the same way humans are. I don't know. There's a bunch of local, and suppose they're not scheming or something. I think there's often the thought that, "No, but the standard of alignment we really care about is not your local ethics, but what happens when you FOOM and become dictator of the universe?

Well, anyway, when is an AI more aligned in humans in an everyday normal sense and when is an AI dictator-ready? And when is an AI more dictator-ready than a human? I think getting to the point where you can meet that standard at least is plausibly not that hard. And so I don't think corrigibility is the only end state here. You can't have other potential options, including potentially sovereign AIs in some sense.

Q: So I was a little surprised to hear you use the example of deontological rule, like don't self-exfiltrate. I thought you were going in the direction of just pure correctability, which boils down to just following instructions: "Here's this guy or this set of people that these instructions you're going to follow," everything else flows out from there. That seems like you're asking it to be one thing instead of multiple things that may conflict your training in opposite directions.

(See: slide on "You do still need to get generalization right enough, though") So I guess the way I've set up the four-step approach is focused on instruction-following as a key feature. So you want to ensure instruction-following in training, check that there's no scheming, ensure you've got generalization to instruction-following on the other inputs you care about. And then final step, have instructions that rule out rogue behavior. So if you want your instructions to be like, "Make me arbitrary money in the future," or something, which you should not instruct your AIs to do probably, then you actually do still need to deal with the corrigibility thing in that context. You need to be like, "But don't break the law and don't do something I would intrusively disapprove of," et cetera. And if you set your AI loose on just making me money, and then you go like, "Wait," then it's incentivized, for example, for you to not change your instructions later or whatever. You have to build in your instructions.

So I think you do still get the problem, but is that the level of how hard is it to write instructions that ensure adequate corrigibility? And I think that's probably not that hard if they're going to be interpreted intuitively, though it's unclear.

Q: I'm not sure this is a good question, so I'll go fast anyway. Sometimes I got the sense that you were strawmanning the MIRI view and I think an example of this might be when you were talking about the pickup speeds and the generalization across the gap. And I certainly would appreciate if you picked on AI 2027 as a concrete example of the type of situation that this might need to apply in and possibly you'll be able to vindicate your arguments in that context, but I would encourage you to think about, let's say it's halfway through the intelligence explosion, they have an AI system that's relatively similar to the LLMs of today, but with neuralese perhaps. And it's called Agent 3, and it's basically doing all the research and it's discovered a new type of architecture that's more human brain inspired that works in a substantially different way and is massively more data-efficient and better at online learning, et cetera. And the plan is to switch over to this new architecture and put copies of the new thing in charge of everything.

And also China sold the weights two months ago, and so you have two months to get this working, go, go, go. That's the sort of generalization gap that you want to be able to cross on the first critical try because reasoning about this new system that you only invented last week that works differently from the current system, and your bosses are telling you that we're going to need a million copies of it and put it in charge of the research as soon as possible, and then it's going to go on blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So a situation like that is, I think, helpful to describe as the sort of thing that we actually seem to be headed towards. So you can either reject that and say, "No, no, no, I think takeoff's going to be slower than that. It's going to take place over several years. There won't be any paradigm shifts like that happening in the middle of takeoff." Or you can be like, "Yep, something like that will be happening and we want our alignment techniques to generalize across that gap and we want..."

Yeah, I appreciate this question. I've been playing fast and loose at my characterization of the argument and the broad MIRI picture of this. I want to communicate some suspicions I have as to underlying generators of ways in which this discourse might be inflected with some aspects that are off, but you're right, I've been playing fast and loose, and I think there's more to say there.

So if we're thinking that the problem is that this generalization is going to be involving a fundamentally new paradigm, I think that's a great reason to be worried that things that helped with safety and the old paradigm won't work anymore. I think that's a more specific picture. I worry sometimes there's a little bit of inflection of there has to be a new paradigm because the current thing is missing the deep core of intelligence or something like that. And I'm like, "Ah, I worry about that."

My default is something like, there can be a fast takeoff, but if you're doing the same techniques, roughly speaking, and you're learning a bunch about how ML works in general, then I agree that things are very scary because they're moving very fast and because China stole the weights and et cetera, et cetera. Normally the scenario I'm thinking about is a little bit more like that. It's like the type of AIs we need to align are in the rough paradigm that we're currently working in. And then if we're going to do a new paradigm, it's a lot harder to say exactly how the safety thing goes and we need to actually have done the relevant science before that. I still think you can get AI 2027 style worries. Even if your story ran without any paradigm shift, but you just amp up on ML and RL, et cetera, I think you can definitely get scared there.

I think my version would probably be, you make a capability leap and then that's when scheming hits. And so your scheming starts concurrent with an increase to the next scale-up of capability or something like that, and then your science starts to fail or your generalization can't be studied in the same way. And I just think that is scary. I think this is a scary situation. I'm not saying it's fine. I mostly want to emphasize the details of the importance of us attending to the specific type of generalization we need to get right. And I think in an incremental world, you can try to minimize the steps, the amount of generalization you're doing at each step and make it as continuous as possible with the stuff you've studied before.

Cool. Thank you everybody. Happy to chat more about this. I'll be around. And like I said, I have an essay online that goes into this argument in more detail, so feel free to check that out.