In my previous post, I talked through the process of identifying the fears underlying internal conflicts. In some cases, just listening to and understanding those scared parts is enough to make them feel better—just as, when venting to friends or partners, we often primarily want to be heard rather than helped. In other cases, though, parts may have more persistent worries—in particular, about being coerced by other parts. The opposite of coercion is trust: letting another agent do as they wish, without trying to control their behavior, because you believe that they’ll take your interests into account. How can we build trust between different parts of ourselves?

I’ll start by talking about how to cultivate trust between different people, since we already have many intuitions about how that works; and then apply those ideas to the task of cultivating self-trust. Although it's tempting to think of trust in terms of grand gestures and big sacrifices, it typically requires many small interactions over time to build trust in a way that all the different parts of both people are comfortable with. I’ll focus on two types of interactions: making bids and setting boundaries.

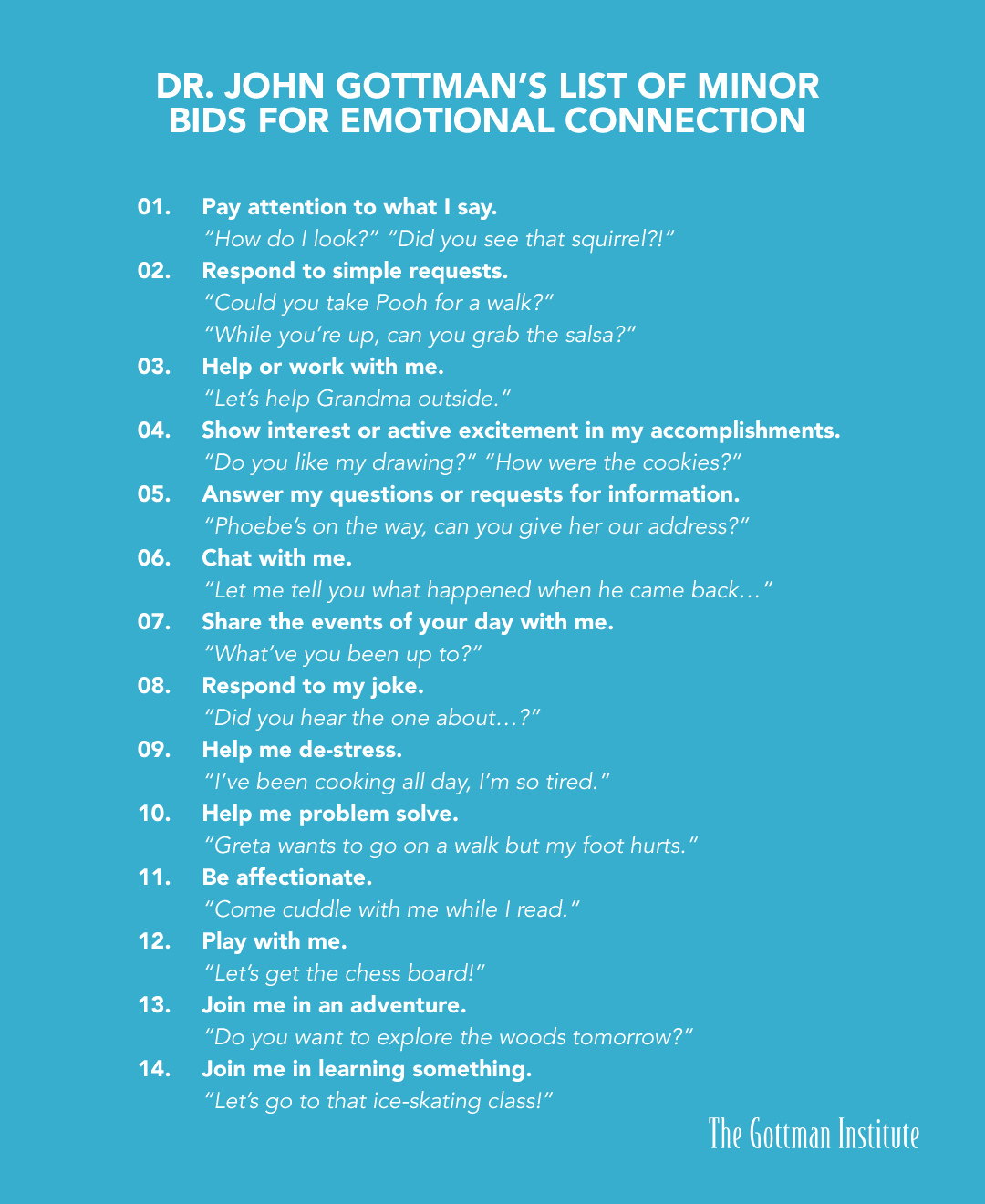

By “making bids” I mean doing something which invites a response from the other person, where a positive response would bring you closer together. You can read about them in the work of John Gottman, who gives many examples:

Sometimes bids are explicit, like asking somebody out on a date. But far more often they’re implicit—perhaps greeting someone more warmly than usual, or dropping a hint that your birthday is coming up. One reason that people make their bids subtle and ambiguous is because they’re scared of the feeling of a bid being rejected, and subtle bids can be rejected gently by pretending to not notice them. Another is that many outcomes (e.g. being given a birthday present) feel more meaningful when you haven't asked for them directly. Some more examples of bids that are optimized for ambiguity:

- Teenagers on a first date, with one subtly pressing their arm against the other person’s, trying to gauge if they press back.

- Telling your parents about your latest achievements, in the hope that they’ll express pride.

- Making snarky comments about your spouse being messy, in the hope that they’ll start being more proactive in taking care of your preferences.

- Asking to “grab a coffee” with someone, but trying to leave ambiguous whether you’re thinking of it as a date.

Of course, the downside of making ambiguous bids is that the other person often doesn't notice that you're making a bid for connection—or, worse, interprets the bid itself as a rejection. As in the example above, a complaint about messiness is a kind of bid for care, but one which often creates anger rather than connection. So overcoming the fear of expressing bids directly is a crucial skill. Even when making a bid explicit renders the response less meaningful (like directly asking your parents whether they're proud of you), you can often get the best of both worlds by making a meta-level bid (e.g. asking your parents to talk about how they express their emotions) which then provides a safer way to bring up your underlying need (e.g. for them to be more positive, or at least less negative, in how they talk to you).

There's a third major reason we make ambiguous bids, though. The more direct our bids, the more pressure recipients feel to accept them—and it’s scary to think that they might accept but resent us for asking. The best way to avoid that is to be genuinely unafraid of the bid being turned down, in a way that the recipient can read from your voice and demeanor. Of course, you can’t just decide to not be scared—but the more explicit bids you make, the easier it is to learn that rejection isn’t the end of the world. In the meantime, you can give the other person alternative options when making the bid, or tell them explicitly that it’s okay to say no.

Ultimately, however, you can’t take full responsibility for other people’s inability to turn down bids. Many people are conflict-averse and feel strong pressure in response to even indirect bids. When someone says something that could be interpreted as a complaint, listeners often rush to reassure them, contradict them, or try to fix it—even when none of these are actually what the complainer is looking for. The frantic need to manage others’ bids becomes particularly noticeable once you’ve experienced the practice of circling, which can be roughly summarized as having a conversation about your emotions without treating any statements as implicit bids. This can be a very uncomfortable experience at first, but being able to respond to bids in a way that isn’t driven by fear is incredibly valuable, and is the core skill behind the second aspect of building trust: setting boundaries.

Setting boundaries is about not accepting bids which a part of you will resent having accepted, and clearly communicating this to the people making the bids—for example, telling a friend when you don’t have the energy to talk about their problems, even if they seem sad. It’s easy to continue accepting bids even if that builds up a lot of resentment over time, because it’s scary to think that someone might resent us for rejecting them. But in most cases setting boundaries isn’t actually a selfish move, but rather an investment in that relationship—not just because it makes you feel more positively towards the other person, but also because it creates safety for them to make other bids. If you’re capable of setting boundaries, then they no longer need to carefully figure out which bids you’ll accept happily and which you’ll accept begrudgingly, and they’ll likely end up having more bids accepted over the long term.

Trust which is built up via fulfilling all bids is fragile—if a bid is ever rejected, that feels like an unprecedented disaster! Trust which is built up via fulfilling the bids that work, and making clear which ones don’t, is much more robust—especially because saying no to a bid is often a starting point, not an ending point. In most scenarios there are compromise options which you’d both be happy with, which it’s much easier to collaboratively discover after you’ve surfaced your true preferences—and which are often much better for the other person than just accepting their original bid, because now they don’t need to second-guess how you really feel.

All of the above applies internally just as much as externally—and usually more so, because our parts are stuck with each other permanently, and have often built up a lot of resentment or hurt over time. An analogy I like here is the process of taming a wild animal—many parts of us are skittish, and so being careful and gentle with them goes a long way. Since those parts often haven't felt empowered to set boundaries before, it might take some costly signals of self-loyalty to convince them that their preferences will actually be respected. That might involve not working on a day you’ve decided to take off even if something urgent comes up; or deciding that a new experience is too far out of your comfort zone to try now, even if you know that pushing further would help you grow in the long term. But enforcing boundaries a few times typically enables you to do more of the thing you originally refused: most things are much less scary when you trust that you’ll let yourself stop if you really want to.

"You must be very patient," replied the fox. "First you will sit down at a little distance from me--like that--in the grass. I shall look at you out of the corner of my eye, and you will say nothing. Words are the source of misunderstandings. But you will sit a little closer to me, every day . . ."