1 Introduction

The person-affecting view is the idea that we have no reason to create a person just because their life would go well. In slogan form “make people happy, not happy people.” It’s important to know if the person-affecting view is right because it has serious implications for what actions should be taken. If the person-affecting view is false, it’s extremely important that we don’t go extinct so that we can then create lots of happy people.

The far future could contain staggeringly large numbers of people—on the order of 10^52, and possibly much more. If creating a happy person is a good thing, then ensuring we have such a future is a key priority. MacAskill and Greaves, in their paper on strong Longtermism, do some back of the envelope calculations and conclude that each dollar spent reducing existential risks increases expected future populations by 10 billion. This sounds outlandish, but it turns out pretty conservative when you take into account that there’s a non-zero chance that the future could sustain very large populations for billions of years.

Unfortunately for person-affecting view proponents, the person-affecting view is very unlikely to be correct. I think the case against it is about as good as the case against any view in philosophy gets.

I was largely inspired to write this by Elliott Thornley’s excellent summary of the arguments for the person-affecting view, which I highly recommend reading. My piece overlaps considerably with his. Separately, Thornley is great—his blog and EA forum account are both very worth reading.

2 The core intuitions and the weird structure of the view

The core intuition against the person-affecting view is that it’s good to have a good life. Love, happiness, friendship, reading blog articles—these are all good things. Bringing good stuff into the world is good, so it’s good to create happy people. I’m quite happy to exist because I get to experience all the joys of life.

The core intuition behind the person-affecting view is that in order to be better, a state of affairs has to be better for someone. It’s good to help an old lady cross the street because that’s better for them. But if you’re creating a person, they wouldn’t have otherwise existed, and so they cannot be better off. Thus, creating a happy person is neutral.

Here is the issue: the person-affecting view’s core intuition is wrong. In addition, the person-affecting view doesn’t live up to this central intuition.

First: why is it wrong? Well, consider a parallel argument: to be bad, an act must leave people worse off. If you create someone, they’re not worse off, because they wouldn’t have otherwise existed. Thus, a machine that spawns babies over a furnace isn’t bad, because it doesn’t harm anyone. This is clearly wrong, yet it’s the same logic as the argument for it not being good to create happy people.

Here’s another parallel argument:

- For something to be good it must benefit someone.

- For something to benefit someone, they must be better off because of it than they would otherwise have been.

- If a person would not have existed absent having been revived from the dead, then reviving them does not make them better off than they would have otherwise been.

- If a person is revived from the dead then they would not have existed absent being revived from the dead.

- So bringing a person back from the dead is not good.

Now, you might reject 2 if you think that eternalism is true. Eternalism is the idea that all times are equally real, so dead people exist—they just don’t exist now. However, if you discovered that eternalism was false, presumably you should still think it’s good to bring people back from the dead.

Here’s a third parallel argument:

- For something to be good it must benefit someone at some time.

- For something to benefit someone at some time, they must be better off because of it than they would otherwise have been.

- If a person’s life is saved then there is no time during which this action makes them better off because they wouldn’t have otherwise continued to exist during those times.

Given that these arguments are wrong, there must be something wrong with the core argument for the person-affecting view. But remember: this core argument was how person-affecting view proponents answer the “it’s good to create people because happy lives are good,” argument. So if the core argument for the person-affecting view is wrong, then the person-affecting view has no answer to the obvious contrary intuition.

Now, where do things go wrong in the crucial argument for the person-affecting view? Let’s lay out premises:

- For something to be good, it must make someone better off.

- If a person wouldn’t have otherwise existed unless some event occurred, then they can’t be better off than they would have otherwise been.

- When people are created, they wouldn’t have otherwise existed.

- So creating a person isn’t good.

In my view, the issue lies either in premise 1 or 2. The phrase “better off,” is ambiguous. It might be that to be better off in scenario A than scenario B, you have to exist in both scenarios. If that’s built into the definition of “better off,” we should reject premise 1—something can be good without making anyone better off by creating a person and giving them a good life.

If that’s not built into the definition, we should reject premise 2. For my sake, you have a reason to prefer that I exist. Because I exist, I get to live, love, and defend the self-indication assumption. I am benefitted by having the opportunity to exist. In that sense, I am better off.

Thus, the core person-affecting argument rests on a subtle ambiguity and has several different absurd implications. This is problem enough. But things get even worse. The person-affecting view doesn’t even live up to the promise of the slogan. If you bought the core argument, you’d assume that the view thought it was neutral to create happy people. But it doesn’t actually think that.

Here is one standard property of neutral things: they tend to be equally good. If pressing button A is neutral, and pressing button B is neutral, then pressing button A isn’t better than pressing button B. So if creating happy people was neutral, then you’d expect all instances of it to be equally good. But it’s clearly not. Compare:

Button A) Creates Bob at welfare level 100.

Button B) Creates Bob at welfare level 10.

Clearly, it is better to press button A than B. But how can this be if they’re both neutral? I guess you can say that not all neutral actions are equal in value—that one neutral act might be better than another. But that is a tough pill to swallow. It seems that all neutral things are equally good—namely, not good at all.

There’s a widespread philosophical view that the better than relation is transitive (supported by powerful arguments of its own). If A is better than B and B is better than C, then A is better than C. Now, if you accept this, you obviously have to think that creating a happy person isn’t neutral. Compare:

Button 1) Creates Bob at welfare level 100.

Button 2) Benefits Joe, who already exists, by bumping him up half a welfare level.

Button 3) Creates Bob at welfare level 10 and benefits Joe, who already exists, by bumping him up one full welfare level.

If creating a happy person is simply neutral, then pressing button 2 is better than pressing button 1. After all, pressing button 1 is neutral, pressing button 2 benefits someone, so it is good. And button 3 is better than button 2, because it provides a greater benefit to an existing person. But clearly button 1 is better than button 3! So if the better than relation is transitive, it can’t be neutral to create a happy person.

I think it’s even worse to deny the transitivity of equal to than better than, especially when the actions being compared are neutral. Phrased a different way, it seems less bad to say that A is better than B, B better than C, and C better than A, than to say A is neutral, B is neutral, C is neutral, but A is better than C. Aren’t all neutral things the same? Neutral things add zero value, and zeros don’t differ in value. As we’ve seen, holding that creating a happy person is neutral inevitably violates this principle.

Another property of neutral things: if you combine them with things that are bad, then they are bad. If it is neutral to press a button that does nothing, and it is bad to poke someone in the eye, then it would be worse to both press a button that does nothing and poke someone in the eye than do nothing. But if we accept this principle and hold that it’s neutral to create happy people, then we must be anti-natalists.

After all, people having children leads to some children being born with a bad life. So if it’s neutral for a person to be born with a good life, and bad to be born with bad lives, then having children in the aggregate is very bad. In fact, in such a case, it would be extremely good to hasten the extinction of life on Earth, even if almost everyone was guaranteed to be born with a great life.

Lastly, if creating a happy person was neutral, the following extremely strange comparison would result. The number after a person will refer to their welfare level. A>B means “A is better than B.”

A: Bob 3, Jane 3, Janice 3

B: Bob 3, Jane 4, Janice 1

C: Bob 3, Jane 3

A>B

B>C.

A=C.

But if A>B because it has more total welfare and more equality, and B>C, then A should be better than C. But it’s not on the person-affecting view because it just has one extra person who is neither well-off nor badly off. B leaves one person better off than C and one newly created person well-off. Now, again, you can get around this by giving up transitivity, but that is not a fun thing to give up.

Thus, the view that creating a happy person is neutral seems totally hopeless. But to their credit, defenders of the person-affecting view don’t actually think it. Instead, they generally say that creating a happy person has imprecise value. It is neither good nor bad—a world with an extra happy person is neither better nor worse nor equal to the preexisting world.

This sounds paradoxical. But in fact it invokes something called incomparability. If two things are incomparable, they can’t be precisely compared—so they’re neither precisely equal in value, nor is one better. It might be, for instance, that if you’re deciding between two different careers or spouses, neither is better than the other. They just can’t be precisely compared.

Incomparability differs from equality in that it’s not sensitive to small changes. If two actions are exactly equal, then if one is slightly improved, it will become better than the other. A one-hundred dollar bill and two fifty-dollar bills are equal in value—but if you added an extra dollar to a one-hundred-dollar bill, then it would have more value. In contrast, if you are deciding between two spouses, and neither strikes you as better than the other, offering you a dollar to take the first over the second would not convince you. Two things that are equal have the same value, so one of them getting a bit of extra value makes it better—two things that are incomparable have value that can’t be precisely compared, so even if one gets a bit better, they still can’t be precisely compared.

So if the world with an added happy person is incomparable with its preexisting state, then we can accommodate all the earlier judgments. Not all things that are incomparable with a preexisting state are equal. A lawyer job may be incomparable with a doctor job, but a lawyer job with a slightly higher salary is better than a lawyer job with a lower salary. And if you combine an incomparable thing with a bad thing, the end result may be neither good nor bad, rather than bad. If I switch from the doctor job to the lawyer job, but I lose nine cents, I’m neither better nor worse off.

What’s wrong with this response?

The first problem is: it just doesn’t live up to the core promise of the person-affecting view. The idea was supposed to be that creating a happy person was neither good nor bad, because it creates a person who wouldn’t have otherwise existed. Where the hell did incomparability come in? If the intuition is “the world isn’t better by the addition of a happy person, because the happy person isn’t better-off,” then creating a happy person should be neutral, rather than incomparable.

If something benefits and harms no one, we don’t usually think it has imprecise value. We just think it’s neutral. Why isn’t creating a happy person like this? Aside from the fact that the person-affecting view doesn’t work if you posit this, what is the explanation supposed to be? There’s a reason that Jan Narveson formulated the person-affecting view as “We are in favour of making people happy, we are neutral about making happy people,” rather than “We are in favour of making people happy, we believe that after making happy people, the subsequent state is incomparable with the initial state, such that it is neither better, nor worse, nor equal, and is thus susceptible to crosswise comparisons of value.”

This is especially strange when one considers why incomparability arises. It standardly arises when there are goods of different kinds that can’t be directly compared. Two jobs may be incomparable because they both have advantages, yet their advantages are too different to precisely measure against each other. Yet this is not how the person-affecting view thinks creating a person works. On the most natural version of the view, there is nothing at stake—no one made better or worse off.

This also leaves the person-affecting view strangely greedy. Because it holds that adding happy people has imprecise value, it can neutralize quality of life improvements. Revisit the earlier case:

A: Bob 3, Jane 3, Janice 3

B: Bob 3, Jane 4, Janice 1

C: Bob 3, Jane 3.

Clearly A>B. And A is incomparable with C. So then B can’t be better than C. But this is an odd result. It means that adding a welfare improvement and creating a happy person leaves the world neither better nor worse, even though it is better for some people and worse for no one. Half the person-affecting slogan is “make people happy.” Now they’re neutral about combining making happy people with making existing people happy.

Intuitively, we’d want to say that A>B, B>C and so A>C. But defenders of the person-affecting view can’t say that, because they think A and C are incomparable. So they either have to deny transitivity or say B and C are incomparable, even though B is the same as C, except it has one existing person made better off and a new well-off person brought into existence. This case, similar to one discussed by Thornley and presented in this paper by Tomi Francis, seems quite decisive.

This means that creating a happy person can swallow up value in either direction—if a world was full of miserable people, and then you flooded it with happy people, on such a view, it would stop being bad, but instead have imprecise value. This isn’t the result that person-affecting view proponents want. This also means that a very bad world isn’t worse than one that’s neither good nor bad.

A second problem with such a view: it doesn’t have the apparatus to answer the core intuition behind the non-person affecting view. This intuition was expressed well by Carlsmith:

My central objection to the neutrality intuition stems from a kind of love I feel towards life and the world. When I think about everything that I have seen and been and done in my life — about friends, family, partners, dogs, cities, cliffs, dances, silences, oceans, temples, reeds in the snow, flags in the wind, music twisting into the sky, a curb I used to sit on with my friends after school — the chance to have been alive in this way, amidst such beauty and strangeness and wonder, seems to me incredibly precious. If I learned that I was about to die, it is to this preciousness that my mind would turn.

This was the problem expressed earlier: life is full of awesome stuff, and so it seems good. Just positing that life lacks precise value doesn’t answer this central argument. We’re still left with the core problem that the central person-affecting intuition has insane implications (e.g. that creating miserable people isn’t bad) and the central non-person-affecting intuition does not, and has no adequate answer.

A third problem is that incomparability is implausible. I can’t defend this judgment in detail, so I encourage you to read these articles that make the case against it more decisively. I find it pretty overwhelming.

Fourth, such views require extremely strange pairwise comparisons. Intuitively, it seems like it shouldn’t be that you’re allowed to pick B over A if they’re the only options, but you have to pick A over B if there’s some third option C. It is odd, in other words, to have the preference structure of the old Sydney Morgenbesser joke:

After finishing dinner, Sidney Morgenbesser decides to order dessert. The waitress tells him he has two choices: apple pie and blueberry pie. Sidney orders the apple pie. After a few minutes the waitress returns and says that they also have cherry pie at which point Morgenbesser says “In that case I’ll have the blueberry pie.”

But the person-affecting view absolutely requires you to have such a preference structure. Suppose you have the following three options:

A) Create Bob at welfare level 5.

B) Create no one.

C) Create Bob at welfare level 10.

If your only options were A and B, you’d be permitted to pick A over B. But given the existence of C, now you’re not allowed to pick A over B. Now, admittedly, this strange preference structure will inevitably result from incomparability, but that seems all the more reason to give up incomparability. How could whether you’re allowed to pick A over B depend on the presence of other options that you’re not taking? Very strange.

What are the takeaways from this section:

- There is a central intuition behind the person-affecting view and the non-person-affecting view. However, the central intuition behind the person-affecting view faces several different decisive objections, and the person-affecting view doesn’t even live up to the slogan.

- The person-affecting view, to remain plausible, can’t actually hold that it is neutral to create happy people. It must hold that creating happy people has imprecise value. But this doesn’t fit with the core intuition which is that creating a happy person doesn’t leave anyone either better off or worse off.

- However, when it holds this, it ends up with the extremely implausible result that sometimes creating happy people and improving the welfare of every existing person is not good—it doesn’t make things better. It also ends up with the result that if there’s a world full of miserable people, and you flood it with happy people, then it will become neither good nor bad. You can get around some of these results by jettisoning transitivity, but that is cost enough of its own.

3 Weird incomparability

We’ve already seen that the person-affecting view has to hold that creating a happy person results in an incomparable world—one neither better, nor worse, nor equal in value. But now consider three options:

- Create Tim at welfare level 10.

- Create no one.

- Create Tim at welfare level 1 trillion.

1 and 2 are incomparable. 3 is vastly better than 1—about a hundred billion times better (though perhaps less if utility is bounded). But here is a principle that holds regarding incomparable goods in nearly every other case: if A and B are incomparable, and C is vastly better than A, then it’s also better than B.

There might be weird exceptions in the case of infinite values that are incomparable, but that is only because infinity times any number is still infinity, and it has enough value to swallow up other values. But in less exotic cases involving incomparable goods, the principle holds. It may be that a lawyer job and a doctor job are incomparable, but if the lawyer job got a trillion times better—say, the salary increased a lot, the workplace become vastly more pleasant, it became more impactful, and you had 364 days off out of the year—then the lawyer job would be better. Incomparability can swallow up small improvements, but not enormous ones.

However, this principle straightforwardly implies that 3>2, which the person-affecting view must deny. This means it must posit a new and very odd form of comparability, not susceptible to any degree of sweetening. Similarly, let’s add to the mix:

- Create Tim at welfare level 10.

- Create no one.

- Create Tim at welfare level 1 trillion.

- Benefit an existing happy person by N units, where N is just enough to make 4 better than 1, rather than incomparable.

4 benefits an existing person by just enough to be better than 1, so 1 doesn’t swallow it up. The person-affecting proponent thus must think 2 is incomparable with 1, 4 is a bit better than 1, 3 is vastly better than 1, and yet 4 is better than 2, while 3 isn’t better than 2. Using symbols, let A>>>>B mean “A is vastly better than B,” and A~B mean “A and B are incomparable,” and “A>B,” mean A is just a bit better than B. The person-affecting view thus gets:

1~2

3>>>>1.

4>1.

3~2.

4>2.

This is very strange. This would be like if Usain Bolt was much faster than me, my brother was just a little bit faster than me, yet my brother beat in a race someone who Usain Bolt didn’t beat. If 3 is vastly better than 1, and 4 is just a bit better than 1, then if 4 beats 2 then surely 3 should as well? Yet such a judgment requires giving up the person-affecting view.

Here’s another odd feature of the person-affecting view: imagine there are two buttons. Button 1 creates Bob at welfare level 100,000. Button 2 boosts his welfare level up to 100,001. It seems natural to think that Button 1 did something much better than button 2. Yet the person-affecting view must deny that, holding that button 2 is good and button 1 isn’t either good or bad.

Here’s another parallel idea: presumably there is some welfare level at which creating someone at the very least isn’t bad. Let’s say that level is ten units of welfare. So now imagine two options:

- Create one person at welfare level 10. Then boost their welfare level 1000 units.

- Create one person at welfare level 1010.

These are presumably equal in value. And yet the first one combines something neutral with something good. The good thing is enough to more than outweigh the swamping of the neutral thing. Thus, it seems the first is good, and the second is just as good, so creating a happy person is good. (And if 1000 units isn’t enough to outweigh the 10 unit swamping, then make it more).

One last case: imagine that Steve already exists. Your two options are:

- Lower Steve’s welfare by 3 units, create Bob at welfare level 1,000.

- Create Bob at welfare level 10.

- Do nothing.

What are you allowed to do here? Plausible principles imply a paradox:

- It seems you’re not allowed to do 2. After all, at just a small cost you could have made Bob’s welfare level much higher.

- It seems you’re not allowed to do 1, because 1 is worse than 3. It’s impermissible to harm a person to create a well-off person when the person-affecting view holds that creating a well-off person is neutral.

- If the other two judgments are correct, then you must do 3. But if your only options were 2 and 3, they’d both be permissible. Adding an extra impermissible option shouldn’t change what you can do!

Thus, plausible principles lead to paradox: you can’t do 1, you can’t do 2, and yet it isn’t true that you must do 3.

Relatedly, suppose you have three options:

- Create no one.

- Create Jane at welfare level 10 and improve Bob’s welfare by 500 units.

- Create Jane at welfare level 100,000.

What should proponents of the person-affecting view say you’re allowed to do. 2. seems obviously impermissible because it is vastly worse than 3. 1. seems impermissible because you could instead benefit Bob by a huge amount and create a well-off Jane. If 1 and 2 are impermissible, then 3 must be obligatory. But if your only options were 3 and 1, then you’d be permitted to pick 1. So then if 3 is obligatory, that runs afoul of the following principle:

Losers Losers Can Dislodge Winners: Adding some option 𝑋 to an option set can make it wrong to choose a previously-permissible option 𝑌, even though choosing 𝑋 is itself wrong in the resulting option set.

This is weird. If you don’t have to pick one option over another, adding a third impermissible option shouldn’t make you pick that option over the other. This will also mean that the person-affecting view sometimes makes it obligatory to create a happy person instead of creating no one.

4 My argument

One objection to the person-affecting view is original to your favorite blogger. Imagine that there are two buttons. Button 1 creates a happy person (Frank) and benefits an existing person (Bob). Button 2 eliminates the benefit to Bob while providing a much greater benefit to Frank. You can only press button 2 after pressing button 1.

So, for example, let’s suppose that button 1 sends Bob a vial of medicine that will allow him to live an extra 3 months, while creating Frank who will live to 70. Then, button 2 would instead give that vial of medicine to Frank, and it would allow him to live 20 extra years instead, so that he lives to 90.

It seems obvious that you should press button 1. After all, it benefits an existing person and makes a new person better off. Similarly, after pressing button 1, you should press button 2. It rescinds a benefit to the existing person while providing a much greater benefit to another person. It’s better to give the vial of medicine to the person who will get 20 extra years from it than the person who will live 3 extra months.

Note: stipulate that button 2 is pressed before the vial reaches Bob. So it doesn’t risk violating rights. Bob hasn’t gotten the medicine—it just rescinds the gift that you would have given him, by default, unbeknownst to him.

But here’s a principle: if you should press a single button that has some effect, and then you should press another button that has another effect, it’s good to press a single button that has both effects. If you should press one button that feeds a homeless person, and another that feeds another homeless person, then it would be good to press a single button that feeds both homeless people.

After all, if it’s worth pressing two buttons to achieve some effect, then it’s also worth pressing one button to achieve the effect. Whether some effect is worth bringing about doesn’t depend on the number of buttons you have to press to bring it about. In addition, we could imagine the way the third button worked was by lowering a popsicle stick down that pressed the other two buttons. This wouldn’t affect whether it was worth pressing, and clearly, if it had such effect, you should press it. If you should press two buttons, then you should press a third button that lowers down a popsicle stick to press them both.

But if you pressed one button to achieve both effects, then that button would simply create Frank and enable him to live 90 years. Thus, it’s worth pressing a single button to create a happy person, and the person-affecting view is false.

As an aside, this argument establishes that creating happy people isn’t just good, but it’s sometimes obligatory. You are presumably required to press both buttons 1 and 2. But if you’re required to do A, and required to do B, you’re required to do C which has the same effects as doing A and B. So you’d be required to press a button that simply creates a happy person. As another aside: if the axiological asymmetry is false, then probably the deontic one is too. If it’s good to create a happy person, then probably one is obligated to do so at no cost. One is usually obligated to make things better at no cost to themselves.

There are three ways you can get off the boat. Now, I’ll explain why none of these are attractive, but additionally, I’ll show later that there’s an axiological parallel and rejecting these doesn’t help avoid that one. In fact, the axiological problem is worse. But first, the three ways you can reject this argument:

- Think it’s not good to press button 1 that creates Frank who will live 70 years and allow Bob to live an extra 3 months.

- Think it’s not good to press button 2 that rescinds the 3 months of extra life benefit to Bob (by simply failing to give him the benefit before he’s even made aware of it) and gives Frank an extra 20 years of life.

- Think that even if you should press each of two buttons, it isn’t necessarily the case that you should press a single button that has the effect of pressing each button.

Why might you reject 1? Well, you might first think that pressing 1 results in an incomparable state of affairs, because creating a happy person has imprecise value which swallows up the benefit of aiding Bob. But then we can simply stipulate that the benefit that button 1 provides to Bob is large enough that creating a new person doesn’t swallow it up.

Similarly, you might reject 1 because you think that 1 is only worth pressing if you won’t later have the option to press button 2. But this is very odd. Learning that after you perform some act, you’ll have the ability to perform another act that is good shouldn’t count against it. I included the following dialogue in my paper to illustrate the strangeness:

Person 1: Hey, I think I will create a person by pressing a button. It is no strain on us and it will make the life of a random stranger better, so it will be an improvement for everyone.

Person 2: Oh, great! I will offer you a deal. If you do that, and you do not give the gift to the stranger, instead, I’ll give your baby 20 million times as much benefit as the gift would have.

Person 1: Thanks for the offer. It is a good offer, and I would take it if I were having the baby. But I am not having a baby now, because you offered it.

Person 2: What? But you don’t have to take the offer.

Person 1: No, no. It is a good offer. That is why I would have taken it. But now that you have offered me this good offer, that would be worth taking, it makes it so that having a baby by button is not worth doing.

Why might you reject 2? I can’t really think of a reason. 2 seems obvious. The only reason you might reject 2 is that 2 in conjunction with 1 simply creates a happy person. Thus, before pressing either, you might plan to reject 2, so that you can benefit an existing person, rather than creating a happy person.

But this is very odd. Once the person already exists, you can make them better off at comparatively small cost. When deciding whether to benefit the person at stage 2, what matter are the benefits to the people who are guaranteed to exist, rather than your plan at an earlier stage.

To see the strangeness, imagine that you can’t remember if Frank was created by button 1 or simply existed for other reasons. Would you really have to look back and see how Frank got created in order to see whether it was worth pressing button 2? If someone else pressed button 1 to create Frank, would you then be allowed to press button 2? We can even imagine that your choice of whether to press 2 is made millions of years after 1. Can such distant actions really make the difference?

It’s even worse because we can stipulate that by pressing button 2, the benefits to Frank are billions of times greater than the lost benefits to Bob. In such a case, it seems worth pressing the button. But that, of course, requires giving up the asymmetry in combination with the other principles.

Now, you can in theory reject 3—thinking that even though each button is individually worth pressing, you shouldn’t press a single button that has both effects. But that is very strange. Why should it matter whether in bringing about the resultant state of affairs, you press one button or two? And what if, as already discussed, the single button works by simply lowering down a popsicle stick that presses the other two buttons? Would it then start being worth pressing, because it simply presses the other two buttons?

In addition, it’s not clear that this helps much. If you think it’s not worth creating a happy person, then you should also think it’s not worth taking a sequence of acts that creates a happy person. But if you should press both buttons, then you should take a sequence of acts that simply creates one happy person.

So I think each principle is extremely plausible. But things get even worse for defenders of the person-affecting view. Because we can make do without needing to talk about benefits to existing people, simply by talking about fortunate states of affairs. To see this, imagine that instead of an agent deliberating about the pressing of the buttons, we simply consider: which button’s press is fortunate?

Button 1, remember, creates an extra happy person (Frank) with, say, 100 utils, and benefits Bob, who already exists, with 50 utils.

Button 2 eliminates the benefit to Bob, and gives Frank an extra 100,000 utils.

Clearly, the world is better if button 1 is pressed than if neither button is pressed. And the world is better if buttons 1 and 2 are pressed than if just button 1 is pressed. By transitivity, therefore, a world where both buttons are pressed is better than one where neither are pressed. But that world just has one extra happy person. Thus, the world gets better with the addition of a happy person.

This version is even harder to get around. The easiest way to get around the early argument was by appealing to facts about sequences of acts—suggesting that you should evaluate the acts differently when they’re part of a sequence. But here, there’s no actor taking a sequence of acts. We’re just comparing states of affairs. It seems obvious that button 1 improves the world, and so does button 2—but if those are right, and the better-than relation is transitive, then adding an extra happy person makes the world better.

What if you deny the transitivity of the better than relation? In such case: STOP! But even then, I think the argument still has force. The purported cases that violate the better than relation generally involve very large sequence of acts. Even if you hold that A>B>C>D…through a million steps>A, it is a lot weirder to think that A is better than B which is better than C, while C is better than A. Violations of transitivity are weirder involving short sequences.

Here is a more modest principle than transitivity:

Short extreme transitivity: If A is vastly better than B, and B is vastly better than C, then A is better than C.

This restricts transitivity in two ways. First, it only requires it holds in sequences where only three things are being compared. Second, it requires that at each step things are getting vastly better. Yet by having button 1 confer a very large benefit on Bob, and button 2 confer a vastly greater benefit on Frank, we can have button 1 being pressed be a lot better than no buttons being pressed, and both buttons being pressed be much better than just button 1 being pressed. Then, by short extreme transitivity, the world gets better with the addition of an extra happy person.

There’s lots more to be said about the argument. You can read my paper on it, and you should ideally cite it up the wazoo so that I can get a job in academia!

5 Thornley’s argument

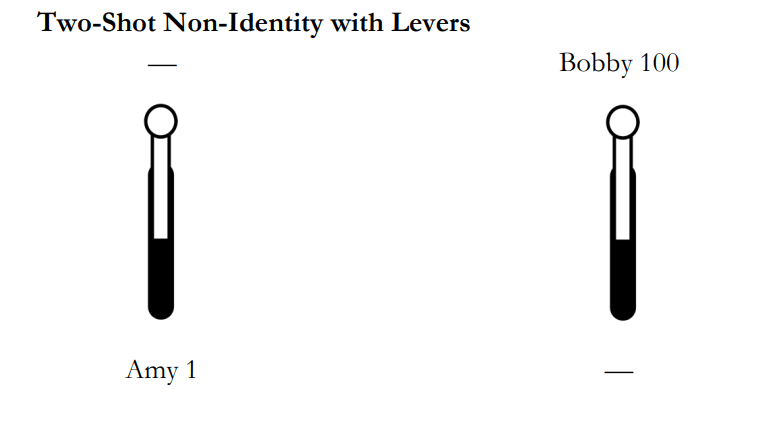

Elliot Thornley has a paper presenting a new argument against the person-affecting view. In this section, I’ll largely summarize Thornley’s paper. Thornley distinguishes between two versions of the view. Imagine that you can either create:

- Amy at welfare level 1.

or:

- Bob at welfare level 100.

The narrow person-affecting view says that we’re allowed to choose either. The wide person-affecting view says we have to create Bob, because his welfare level is higher. Thornley then argues that neither wide views nor narrow views can be right.

5.1 Narrow views

The central judgment of narrow views is pretty counterintuitive. It seems like you have to create Bob because his welfare level is higher. But narrow views have bigger problems. Imagine you can create one of the following:

- Amy at welfare level 1.

- Bob at welfare level 100.

- Bob and Amy at welfare level 10.

What are you permitted to do in this case? It doesn’t seem like you’re morally permitted to choose 1. It seems wrong to create Amy at welfare level 1, when you could instead create her at welfare level 10, and also create Bob. This would be better for Amy and worse for no-one. How could you possibly justify to Amy taking 1 over 3?

Are you permitted to choose 3? Intuitively, it seems like the answer is no. 2 is very good for Bob. It has higher average welfare and total welfare than 3. It is very good for Bob, rather than just being mediocre for Bob, and also mediocre for Amy. If you can do something that’s either mediocre for two people who you create or very good for one person you create, you should do the second.

Here’s one other argument against you being permitted to pick 3: we can imagine decomposing 3 and 2 into two separate actions. Imagine that the way to do either 3 or 2 is first by pressing one button which creates Bob at welfare level 10. Then, after pressing that, there are two other buttons, but you can only press one. The first of those buttons would boost Bob’s welfare level from 10 to 100, while the second would create Amy at welfare level 10.

After pressing the first button, the choice between 2 and 3 is between boosting the welfare of a person who is guaranteed to exist by a lot and creating a person at vastly lower welfare. But this is the person-affecting view we’re talking about! It prefers benefitting existing people to creating new happy people. It seems especially obvious that if you can benefit a person who will exist by much more than the welfare level of the person you might create, you should benefit rather than create.

So far, we’ve argued that neither 3 nor 1 is permissible on the narrow view. This would imply that the only permissible option is 2—creating the person at welfare level 100. However, this implies the following (quoted directly from Thornley’s paper):

Losers Can Dislodge Winners: Adding some option 𝑋 to an option set can make it wrong to choose a previously-permissible option 𝑌, even though choosing 𝑋 is itself wrong in the resulting option set

Narrow views imply that in the choice between 1 and 2, you can choose either. But why in the world would adding 3, which is itself impermissible to take, affect that? Adding some other choice you’re not allowed to take to an option set shouldn’t make you no longer allowed to choose a previously permissible option. This would be like if you had two permissible options: saving a child at personal risk, or doing nothing, and then after being offered an extra impermissible option (shooting a different child), it was no longer permissible to do nothing. WTF?

Thus, it seems like there are strong arguments against every single version of the narrow person-affecting view. What about the wide view?

5.2 Wide views

Wide views, remember, hold that if we can either create:

- Amy at welfare level 1.

- Bob at welfare level 100.

We’re required to pick 2. Person-affecting views also imply that in the following two cases, either option is permissible.

Just Bob:

- Create Bob at welfare level 100.

- Create no one.

Just Amy:

- Create Amy at welfare level 1.

- Create no one.

But now let’s imagine that first you’re confronted with Just Bob, and then with Just Amy. Are you allowed to create no one in Just Bob, and then create Amy in Just Amy? There are two answers that can be given:

- Yes.

- No.

(I can’t think of a third option, though maybe Graham Priest can!)

Thornley calls the first class of views permissive wide views. These say that you’re always allowed to decline to create the better-off person, and then to create the worse-off person. In contrast, restrictive wide views say you’re never allowed to decline to create the better-off person, and then to create the worse-off person. So permissive wide views say that you can create no one in Just Bob and Amy in Just Amy, while restrictive wide views deny that.

5.2.1 Permissive wide views

Permissive wide views seem to have problems. First of all, they imply that one can permissibly create a worse off person rather than a better-off person. So if you know that if you conceived a child later, they’d have a higher welfare level, permissive views imply that you don’t have to wait.

Second, permissive views care a weirdly large amount about morally irrelevant factors, like whether two acts are chained together as one act. Imagine that there are two levers. If the first one is left up, then Amy will be created at welfare level 1, while if it’s pushed down, she won’t be created. The right lever, if pushed up, will create Bob at welfare level 100. Imagine that you have to first lock in your decision regarding Amy’s lever, and then decide what to do with Bob’s lever.

On this view, you’re allowed to first lock in creating Amy at welfare level 1 by keeping her lever up, and then not create Bob by keeping his lever down. But now imagine that someone ties the levers together, so pushing Amy’s lever will force Bob’s lever to be down too. Now, when deciding between pushing Amy’s lever, you are deciding between creating Amy at welfare level 1 and Bob at welfare level 100. In such cases, wide views imply you have to create Bob. This has the odd consequence that whether you’re allowed to take a sequence of acts leading to some sequence of levers being left up, and effects being achieved, depends on whether it comes from two separate lever movements or just one.

The core problem with permissive wide views is that it holds that you’re permitted to predictably take a sequence of acts to create just Amy at welfare level 1 rather than Bob at welfare level 100, but you’re not allowed to take a single act that creates just Amy at welfare level 1 rather than Bob at welfare level 100. Thus, it holds that by turning a single act into a sequence of two acts, its moral status changes significantly. This is very hard to believe.

5.2.2 Restrictive wide views

Restrictive wide views, remember, say that if you’re given the following sequence of decisions:

Just Amy:

- Create Amy at welfare level 1.

- Create no one.

Just Bob:

- Create Bob at welfare level 100.

- Create no one.

You’re not allowed to create no one in Just Bob and Amy in Just Amy. This is similar to how if you’re given the choice to either just create Bob or Amy, you have to pick Bob because he’d be made much better off. What’s wrong with such views?

Well, first of all, they don’t fit well with the intuitions of those who have person-affecting intuitions. They imply that if a person has created Amy in Just Amy, then they are required to create Bob in Just Bob (otherwise they’d have taken an impermissible sequence of acts).

Second, they imply that permissibility depends on other acts that don’t seem to matter. We could imagine that you made the choice of whether or not to create Amy in Just Amy billions of years in the past—why would that have anything to do with whether you are required to create Bob now? Similarly, such views imply that if you’re advising your friend on whether to have a child, you need to know whether they declined to have a totally unrelated child at a higher welfare level in the distant past. What?

Why would this matter at all? If your friend could have a very happy child, why in the world would it matter if they declined, at some point a long time ago, to have an even happier child? In fact, such a view ends up violating the spirit of the restrictive wide views.

Imagine that a million years in the past, your friend had one of the following two choices but can’t remember which:

- Just Chris: create Chris at welfare level 10 or do nothing.

- Just Joe: create Joe at welfare level 1,000 or do nothing.

Your friend at that time decided not to create.

Note: your friend wasn’t choosing between creating Chris and Joe. Instead, they either were in the decision problem described by Just Chris or Just Joe, but they can’t remember which. They think the odds were 50% that the decision-problem in question was Just Chris and 50% that it was Just Joe.

In five minutes, your friend will learn which situation they were in. Then they’ll have the following options:

- If Just Chris then Frank at 100: If they faced the problem in Just Chris, then their option will be to create Frank at welfare level 100.

- If Just Joe then Frank at 500: If they faced the problem in Just Joe, then their option will be to create Frank at welfare level 500.

This view bizarrely implies that even though Frank has vastly more welfare level in 2 than 1, in 2 they’d have no obligation to create Frank while in 1 they would. Oh and the difference is that in 1, a million years in the past, they had the choice to create someone else. Does that sound plausible to you?

Things get even worse. Here is a plausible principle:

Obligations Meeting: if

- There are two acts

- The first fulfills an obligation if you can do it, and the other does not fulfill an obligation if you can do it.

- The odds are equal that you’ll be able to perform both acts.

- Both acts impose no personal cost.

- You are choosing between raising the odds of performing the obligatory act by some amount or raising the odds of performing the non-obligatory act by some amount.

then:

- It is better to raise the odds of performing the obligatory act.

This is pretty abstract, so let me give an example. Imagine that you either think there’s a 50% chance you’ll be able to save a life at no cost or a 50% chance you’ll be able to give a child a cake at no cost. Suppose that giving a child the cake is not obligatory, while saving a life is. You think that there’s only a 40% chance that you will give the child a cake, and there is also only a 40% chance that you’ll save the child’s life. You can either increase the odds of giving the child the cake by 20% or increase the odds of saving the life by 20%. In such a situation, you ought to do the latter—you ought to increase the odds of saving the life by 20%.

This principle seems trivial. And yet restrictive wide views either violate it or violate ex-ante Pareto. Suppose we’re back to the earlier scenario, where at some time in the past, there was a 50% chance you faced:

- Just Chris: create Chris at welfare level 10 or do nothing.

and a 50% chance you faced.

- Just Joe: create Joe at welfare level 1,000 or do nothing.

Now, in five minutes, you’ll learn which action you took, and then have the following options.

- If Just Chris then Frank at 100: If they faced the problem in Just Chris, then their option will be to create Frank at welfare level 100.

- If Just Joe then Frank at 500: If they faced the problem in Just Joe, then their option will be to create Frank at welfare level 500.

If you faced Just Chris then creating Frank is obligatory, while if you faced Just Joe, it’s not. So, let’s imagine you currently face the following options:

- If you declined to create Chris in the past, increase the odds you’d create Frank by 50%.

- If you declined to create Joe in the past, increase the odds you’d create Frank by 50%.

Obligations Meeting implies you ought to take the first. Yet this is very hard to believe. Taking the second is better for Frank—it raises the odds of him being created at a higher welfare level, rather than a lower welfare level—and affects no one else. So either adoptees of restrictive wide views must give up Obligations Meeting or ex ante Pareto, which is the idea that you should do something if it expectedly benefits some people and expectedly harms no one.

5.2.3 Intermediate views

One could have a view that’s somewhere in the middle, neither a completely permissive view nor a completely restrictive view. For example, perhaps it’s only wrong to create Amy and fail to create Bob if at the time you created Amy, you foresee that you’ll have the option to either create Bob or not. However, such views will still hold that if advising your friend whether to have kids, you’ll need to know whether at some earlier point, they had the option to have a happier child and foresaw their present choice. This is counterintuitive.

Additionally, every version of the wide person-affecting view will inevitably have to either care about causally unrelated acts in the distant past or hold that whether it’s okay to create one person and not another depends on whether this is via moving two lever in two motions, or two levers in one motion.

To see this, imagine there’s currently a lever that is up. That lever, if it remains up, will create no one, while if it’s down, it will create Amy at welfare level 1. There’s another lever that is up, which will create Bob at welfare level 100 if it remains up, and no one if it’s down. The levers are tied together, so either they’ll both be up or they’ll both be down.

Wide person-affecting views hold that it’s impermissible to push the lever down in this case, for doing so will create Amy at welfare level 1 instead of Bob at welfare level 100.

Helpful diagram taken from Thornley’s paper.

Thus, so long as tying the levers together doesn’t affect what you’re allowed to do, it would be impermissible to perform two acts, the first putting Amy's lever down and the second putting Bob's lever down. Thus, if you put Amy’s lever down, it’s impermissible to put Bob’s lever down. This would mean that whether it’s permissible to put Bob’s lever down would depend on whether you created Amy—even if that was in the distant past. Thus, all views must either think that tying two levers together affects whether you can permissibly pull some sequence of them or must care about causally isolated and seemingly irrelevant past acts.

5.3 Conclusion (of this section)

Every version of the person-affecting view, then, has problems in one of Thornley’s cases. The following chart shows the pattern.

6 Arguments for the person-affecting view?

One of the things that’s remarkable about the person-affecting view is that as best as I can tell, there isn’t much that’s even said in its favor. The main argument for it, as already discussed, has serious problems. What else is said in its favor?

It’s often claimed the view is intuitive. Surely we’re not obligated to have children just because they’d be happy? But I don’t think it really is intuitive. The axiological person-affecting view just says it’s good to create a happy person, for their sake, all else equal. That strikes me as the natural view. It’s good to be alive.

Now, one can deny that we’re obligated to have kids without accepting the person-affecting view. No one denies that it’s good to give away a kidney, but people do deny that it’s obligatory. The person-affecting view has to hold that it’s not good to create a happy person, not just deny that it’s obligatory if doing so is personally costly.

If a person could create galaxies full of happy people at no cost—people who’d be grateful for being alive and love every second of life—it strikes me as very intuitive that doing so would be obligatory. It is one thing to hold on to an intuitive view when there are strong objections. But the person-affecting view isn’t even intuitive.

Another thing people will sometimes say in defense of the procreation asymmetry is that it helps avoid the repugnant conclusion. The repugnant conclusion is the idea that a world with tons and tons of barely happy people might be better than one full of very happy people, so long as the first world was sufficiently more populous, and thus had more total welfare. I find this objection very strange:

- There are lots of views that avoid the repugnant conclusion other than the asymmetry. These views have real costs, but many fewer ones than the person-affecting view. If you want to avoid the repugnant conclusion without accepting the person-affecting view, probably you should go in for a critical level view, which says that if your welfare level is below some low but positive threshold, you coming into existence is unfortunate.

- The asymmetry doesn’t give obvious help for avoiding the repugnant conclusion. By default, it seems to say the world full of happy people and more numerous barely happy people are incomparable. Now, you can make a more precise version of the view that doesn’t hold that, but you can adopt an analogous non-person-affecting view.

- I don’t actually think there is good reason to avoid the repugnant conclusion. I think the repugnant conclusion is simply correct.

Lastly, it’s sometimes said that the person-affecting view can explain the intuition that it’s worse to create a miserable person than to fail to create a well-off person. There’s an intuitive asymmetry between how good it is to create a happy person and how bad it is to create a miserable person.

First of all, I don’t actually think this intuitive view is defensible, for reasons I gave in my Utilitas paper. But second and more importantly, you can hold this much more modest asymmetry without going all the way and thinking it isn’t good at all to create a happy person.

It’s possible I’m missing something, but I really don’t see the person-affecting view’s appeal. I feel about it the way Laurence BonJour described feeling about physicalism:

As far as I can see, [it] is a view that has no very compelling argument in its favor and that is confronted with very powerful objections to which nothing even approaching an adequate response has been offered.

7 Conclusion

The person-affecting view says that while one ought to make existing people better-off, there isn’t moral reason to create a person just because their life would be good. The view is intuitive to lots of people, but it faces a number of serious objections. Of the ones discussed:

- It conflicts with the very powerful intuition that it’s good to be alive if your life goes well.

- The core argument for the procreation asymmetry can’t be right because it implies that it’s never good to bring someone back from the dead or save their life. Most concerningly, it implies that it isn’t bad to create a very miserable person.

- The view ends up saying that creating a happy person has imprecise value, instead of being neutral. But this doesn’t live up to the core intuition, which is that creating a happy person neither benefits nor harms anyone.

- Because creating a happy person, on the view, has imprecise value, it can swallow up improvements in the world. This strangely implies that even if you create well-off people and make everyone better off, this won’t necessarily make things better. So ironically the person-affecting view ends up not even preferring acts that make everyone better off!

- It must hold to incomparability, despite a number of strong objections to incomparability.

- It must hold that whether you’re permitted to choose A over B will sometimes depend on whether there’s some other unrelated choice that you’re not making.

- It implies that even if A and B are incomparable, and C is vastly better than B, C may not be better than A.

- It implies that if 1 and 2 are incomparable, 3 is vastly better than 1, 4 is just a bit better than 1, and 3 and 2 are incomparable, 4 might be better than 2. In other words, the thing vastly better than 1 doesn’t beat 2, but the thing just a bit better than 1 does.

- It has strange results across cases where you have 3 options: create a person at a low welfare level, create them at a much higher level and harm someone a bit, or do nothing.

- If you can either create no one, create one person and benefit another, or create the first person at a much higher welfare level, the view implies either: 1) adding an impermissible option to a set of choices can make a previously permissible option no longer permissible and sometimes one is required to create a happy person instead of creating no one; 2) one can be justified in taking an action that is much worse for one person and only slightly better for another; or 3) one can permissibly do what’s worse for some and better for none.

- It implies that if something is neutral, and you combine it with something very good, the end product might be neutral. This is so even if the good thing is more than good enough that the neutral thing can’t swallow it up.

- Implies either that: 1) you shouldn’t press a button that makes an existing person much better off and creates a well-off person; 2) you shouldn’t redirect a benefit from an existing person to provide a much larger benefit for one who is guaranteed to exist; 3) it matters whether some state of affairs is brought about by one act or a sequence of acts. Also probably has to give up on transitivity, and a softened version of transitivity that even transitivity deniers should mostly accept.

- It implies something very strange in Thornley’s case involving levers.

This is an impressively large number of serious objections. The person-affecting view has a defective structure, which makes it easier to proliferate objections. In light of the sheer number of powerful objections, and nothing very convincing to be said in its favor, I think it is clear that the least costly move is to simply abandon the view that implied such absurdity. And there are even more objections that I haven’t mentioned. When you have a judgment that isn’t even widely shared, and it has this many problems, the sensible thing to do is give it up.

The versions of person-affecting views that are to me best motivated, most intuitive and most plausible let go of axiology as normally conceived. They don't have a single privileged "objective" impartial order over possible outcomes, and they violate the independence of irrelevant alternatives, but there are straightforward explanations for how those alternatives come to not actually be irrelevant. See:

I mean, that might help with a few problems, but doesn't help with a lot of the problems. Also, it just seems so crazy. Giving up axiology to hold on to a not even very widely shared intuition? Giving up the idea that the world would be better if it had lots of extra happy people and every existing person was a million times better?

I think we have very different intuitions.

I don't think giving up axiology is much or any bullet to bite, and I find the frameworks I linked

The problems with axiology also seem worse to me, often as a consequence of failing to respect what individuals (would) actually care about and so failing at empathy, one way or another, as I illustrate in my sequence.

What do you mean to imply here? Why would I force myself to accept axiology, which I don't find compelling, at the cost of giving up my own stronger intuitions?

And is axiology (or the disjunction of conjunctions of intuitions from which it would follow) much more popular than person-affecting intuitions like the Procreation Asymmetry?

I think whether or not a given person-affecting view has to give that up can depend on the view and/or the details of the hypothetical.

At a basic level better, not necessarily the things they care about by derivation from other things they care about, because they can be mistaken in their derivations.

Moral realism, that there's good or bad independently of individuals' stances (or evaluative attitudes, as in my first post) seems to me to be a non-starter. I've never seen anything close to a good argument for moral realism, maybe other than epistemic humility and wagers.

Want to come on the podcast and argue about the person-affecting view?

Probably our disagreements are too vast to settle much in a comment.

Of interest, see the comments on Thornley's EA Forum post. I and others have left multiple responses to his arguments.

Here's how I'd think about "4 My argument", in actualist preference-affecting terms[1]:

My preferences will differ between pressing button 1 and not pressing button 1, because my preferences track the world's[2] preferences[3], and the world's preferences will differ by Frank's. Then:

See this piece for more on actualist preference-affecting views.

Past, current and future, or just current and future.

Or also desires, likes, dislikes, approval, disapproval, pleasures in things, displeasures in things, evaluative attitudes, etc., as in Really radical empathy.

I'd guess this is pretty illustrative of differences in how we think about person-affecting views, and why I think violations of "the independence of irrelevant alternatives" and "Losers Can Dislodge Winners" are not a big deal:

Run through the reasoning on the narrow view with and without 3 available and compare them. The differences in reasoning, ultimately following from narrow person-affecting intuitions, are why. So, the narrow person-affecting intuitions explain why this happens. You're asking as if there's no reason, or no good reason. But if you were sufficiently sympathetic to narrow person-affecting intuitions, then you'd have good reasons: those narrow person-affecting affecting intuitions and how you reason with them.

(Not that you referred directly to "the independence of irrelevant alternatives" here, but violation of it is a common complaint against person-affecting views, so I want to respond to that directly here.) 3 is not an "irrelevant" alternative, because when it's available, we see exactly how it's relevant when it shows up in the reasoning that leads us to 2. I think "the independence of irrelevant alternatives" has a misleading name.

And then this to me seems disanalogous, because you don't provide any reason at all for how the third option would change the logic. We have reasons in the earlier hypothetical.