This post introduces the issue of ‘high-hanging fruits’ and identifies possible avenues of action. The epistemic status of this post is extremely rough. I would in particular welcome suggestions for more concrete scenarios than what I suggest below.

1. Possible Scenarios

Consider two possible scenarios:

- Due to shifts in the political climate, we are reasonably confident that animal advocacy will be unusually tractable in the next four years. Experts believe that the most effective intervention method is mass street-level political advocacy. However, there is one catch: the intervention will be effective only if more than x number of people are mobilised.[1] Otherwise, the intervention will have little beneficial effects. The EA community can help ensure that more than x number of people are mobilised within four years, but only if it diverts significant amounts of resources away from other cause areas during that period.

- Compelling evidence suggests that extremely dangerous climate feedback loops will occur when global warming reaches 2°C. However, scientists believe that some extremely effective intervention may become available in three years. Once the intervention becomes mature, y amount of funds needs to be invested extremely quickly for us to realistically avoid hitting 2°C. We can expect funding from non-EA sources to be insufficient. The EA community can ensure enough funding for the intervention only if it starts saving funds now and subsequently spend virtually all saved financial resources on the intervention once it becomes available.

2. What are ‘High-hanging Fruits’?

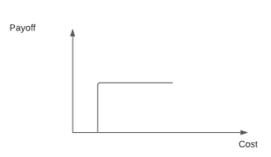

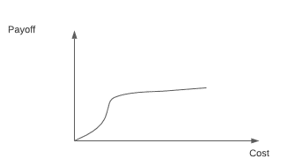

Both scenarios described above are instances of what we might call ‘high-hanging fruits’. ‘High-hanging fruits’ are special cases of increasing marginal returns.[2] In both above scenarios, a critical threshold of resources is required in order to achieve a payoff. In other ‘high-hanging fruit’ cases, there may not be a discrete threshold for a payoff. Rather, there might be continuous increasing marginal returns until a certain point. See figure 1 for representations of cost/payoff functions for ‘high-hanging fruits’.

Figure 1: Cost/Payoff Functions in High-Hanging Fruit Scenarios

If reaching a ‘high-hanging fruits’ requires actions by multiple parties, then it presents a coordination problem, where reaching the optimal outcome requires multiple agents acting on a joint strategy.

3. Importance of ‘High-hanging Fruits’

There are at least three reasons for paying attention to ‘high-hanging fruits’:

- High-hanging fruits are, by definition, high value.

- High-hanging fruits may be prevalent.

- High-hanging fruits are likely to be neglected.

Since the first is mostly self-explanatory, we will only discuss the other two reasons.

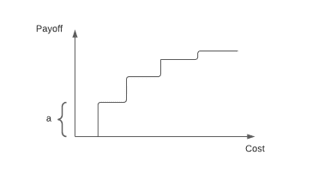

Why might high-hanging fruits be prevalent? Does this not contradict the standard assumption of diminishing marginal returns? Surprisingly, ‘high-hanging fruits’ are compatible with diminishing marginal returns. To see why, we can first observe that many realistic cost/payoff functions have a staircase structure (see figure 2). This staircase structure exists whenever payoffs come in discrete units.[3]

Figure 2: Example Staircase Function

We can see that the staircase function in figure 2 has local increasing marginal returns, but global diminishing marginal returns. When the amount of resource needed for an additional unit of payoff (or a) is large enough to require resources from multiple agents, the payoff constitutes a ‘high-hanging fruit’.

Lastly, ‘high-hanging fruits’ are likely to be neglected in the EA community because of our assumption of decreasing marginal returns and ‘pick the low-hanging fruit’ approach. One of the most common criticisms of EA – that it ignores systematic change – maybe understood in terms of high-hanging fruits. The argument can be understood as saying that EA’s focus on low-hanging fruits leads it to ignore possible high-hanging fruits which require radically high costs.

4. Potential Actions

To act optimally when there are high-hanging fruits, the EA community needs to do two things: 1) identify potential ‘high-hanging fruits’, and 2) coordinate our joint response.

Possible suggestions to achieve these goals include:

- Funding directed toward identifying ‘high-hanging fruits’

- Dedicated space on EA Forum to share potential ‘high-hanging fruits’ or other coordination opportunities.

- Sessions in EA Global or other events dedicated to sharing information about potential ‘high-hanging fruits’ and coordinating our joint strategy.

More integrated finance between EA organizations to allow for more flexibility in resource allocation.

[1] Past evidence suggests 3.5% of the population as a threshold for significant political change.

[2] For relevant discussion, see: Broi, A. (2019). Effective Altruism and Systemic Change. Utilitas, 31(3), 262-276.

[3] For example, consider the distribution of bed nets, or setting up new EA organizations. In each case, a critical threshold of resources is needed to obtain each additional unit of payoff (i.e., each additional bed net or each additional functional EA organization)

I’m glad to see other people following this line of argument :)

I agree that many true payoff functions are likely to have high-hanging fruits, e.g. any cause area aiming at social change that requires reaching a breaking point would have such a payoff function.

However, it's expected payoff functions we're interested in, i.e. how we imagine the true payoff function to look like given our current knowledge. I’ve also thought a bit about whether there would "high-hanging fruits" in this sense and haven’t been able to come up with clear examples. So, like Harrison, I would take issue with your second claim that "high-hanging fruits may be prevalent". I cannot think of any cause area/interventions which could plausibly be modelled, given our knowledge, as having high-hanging fruits on a sufficiently large scale (unlike the examples in your footnote 3, which have increasing marginal returns at a very small scale).

This is because when we take into account our uncertainty, the expected payoff function we end up with is usually devoid of high-hanging fruits even if we think that the true payoff function does have high-hanging fruits. This happens, for example, when we don’t know where the threshold for successful change (or the stairstep in the payoff function) lies. And the less information we have, the less increasing marginal returns our expected payoff function will have. I think this applies very much to the two possible scenarios you give.

The most promising examples of expected payoff functions with high-hanging fruits I can think of are cause areas where the threshold for change is known in advance. For example, in elections, we know the required number of votes that will lead to successful change (e.g. passing some law). If we know enough about how the resources put into the cause area convert into votes, our expected payoff function might indeed have high-hanging fruits. (However, in general we might think it would be increasingly harder to "buy" votes, which might imply diminishing marginal returns.)

In any case, I would also be very interested in any convincing real-life example of expected payoff functions with high-hanging fruits.

I think it’s good to consider these kinds of hypotheticals, and I don’t know if I’ve seen it done very often (although someone may have just expressed similar ideas in different terms). I’m also a big fan of recognizing stairstep functions and the possibility of (locally) increasing marginal utility—although I don’t think I’ve typically labeled those kinds of scenarios as “high-hanging fruits” (which is not to say the label is wrong, I just don’t recall ever thinking of it like that). That being said, I did have a couple thoughts/points of commentary:

• There are a variety of valid reasons to be skeptical of such “high-hanging fruit” and favorable towards “low-hanging fruit”—a point which I think other people would be more qualified to explain, but which relates to e.g., the difficulty of finding reliable evidence that massive increases in effort would have increasing marginal returns (since that may mean it hasn’t been tested at the theorized scale for impact yet), the heuristic of “if it’s so obvious and big , why are we only now hearing about it” (when applicable/within reason of course), the 80-20/power law distribution principle combined with the fact that a decent amount of low-hanging fruit still seems ripe for picking (e.g., low-cost, high-impact health interventions that still have room for funding), and so on.

• I suspect that as the benefits of/need for mass mobilization become fairly obvious, the general public would be more willing to mobilize, making the EA community less uniquely necessary (although this definitely depends on the situation in question).

• The EA community may not be sufficiently (large*coordinated) to overcome the marginal impact barriers.

• Applying the previous points to the scenarios you lay out (which I recognize are not the only possible examples, but it still helps to illustrate): for hypothetical 2, regarding climate change, this seems to be a case where it seems very unlikely that the general public will fail to support such a promising intervention while the EA community would be the unique tipping point to reach massive impact; in hypothetical 1, regarding animal advocacy, such a situation seems fairly unlikely when considering the reasoning behind diminishing marginal returns and historical experience with animal advocacy (e.g., there are going to be people who are difficult to convince), and again it seems unlikely (albeit less unlikely) that EAs would be the unique tipping point for massive impact.

• Especially considering the previous points, I don’t know how widespread/bad the assumptions of diminishing marginal returns in the EA community actually are in practice relative to its inaccuracy. I think it probably is an area for improvement/refinement, but it’s always possible to overcorrect, and I suspect that when/where increasing marginal returns becomes fairly obvious EAs would do a half-decent job of recognizing it (at least relative to how well they would recognize it if they thought about these scenarios more often).

I had similar thoughts , too. My scenario was that at a certain point in the future all technologies that are easy to build will have been discovered and that you need multi-generational projects to develop further technologies. Just to name an example, you can think of a Dyson sphere. If the sun was enclosed by a Dyson sphere, each individual would have a lot more energy available or there would be enough room for many additional individuals. Obivously you need a lot of money before you get the first non-zero payoff and the potential payoff could be large.

Does this mean that effective altruists should prioritise building a Dyson sphere? There are at least three objections:

Please do not misunderstand me. I am very sympathetic towards your proposal, but the difficulties should not be underestimated and much more research is necessary before you can say with high enough certainty that the EA movement as a whole should prioritise some kind of high-hanging fruit.