Previously: Epistemic Hell

--

The Journal of Controversial Ideas was founded in 2021 by Francesca Minerva, Jeff Mcmahan, and Peter Singer so that low-rent philosophers could publish articles in defense of black-face Halloween costumes, animal rights terrorism, and having sex with animals. I, for one, am appalled. The JoCI and its cute little articles are far too tame; we simply must do better.

And so I propose The Journal of Dangerous Ideas (the JoDI). I suppose it doesn’t go without saying in this case, but I believe that the creation of such a journal, and the call to thought which it represents, will be to the benefit of all mankind.

What is a dangerous idea?

an idea whose birthing harms the world; an idea whose existence represents a threat to person or creature (to the good ones, not the bad ones which should be threatened); an idea which possesses the quality of being dangerous (like hardcore pornography, “you know it when you see it”).

I reckon there are many ways in which an idea can be dangerous: technologically dangerous of course, but also scientifically dangerous, philosophically dangerous, socially dangerous, artistically dangerous, spiritually dangerous, and so on and so forth.

Some Examples

- The Journal of Dangerous Ideas itself

- Ideas for scamming methods

- Ideas for (bio)weapons or torture techniques

- Ideas for charlatanry (medical or otherwise) designed to exploit psychosocial vulnerabilities (e.g. ?)

- Ideas for “challenges” (Skull-breaker challenge, Pass out challenge) that serve no purpose other than maiming/killing stupid teenagers

- Ideas for pseudoscientific ideas with the potential for high memetic virality (a plausible-sounding but flawed biological theory that is tailor-made to be co-opted by bad actors of some kind, e.g. neo-nazis, religious zealots, etc.)

- The idea that everything is traumatic and everyone should be hyper-aware of mental health at all times.

- The idea that ideas can be dangerous

- Your dangerous idea here

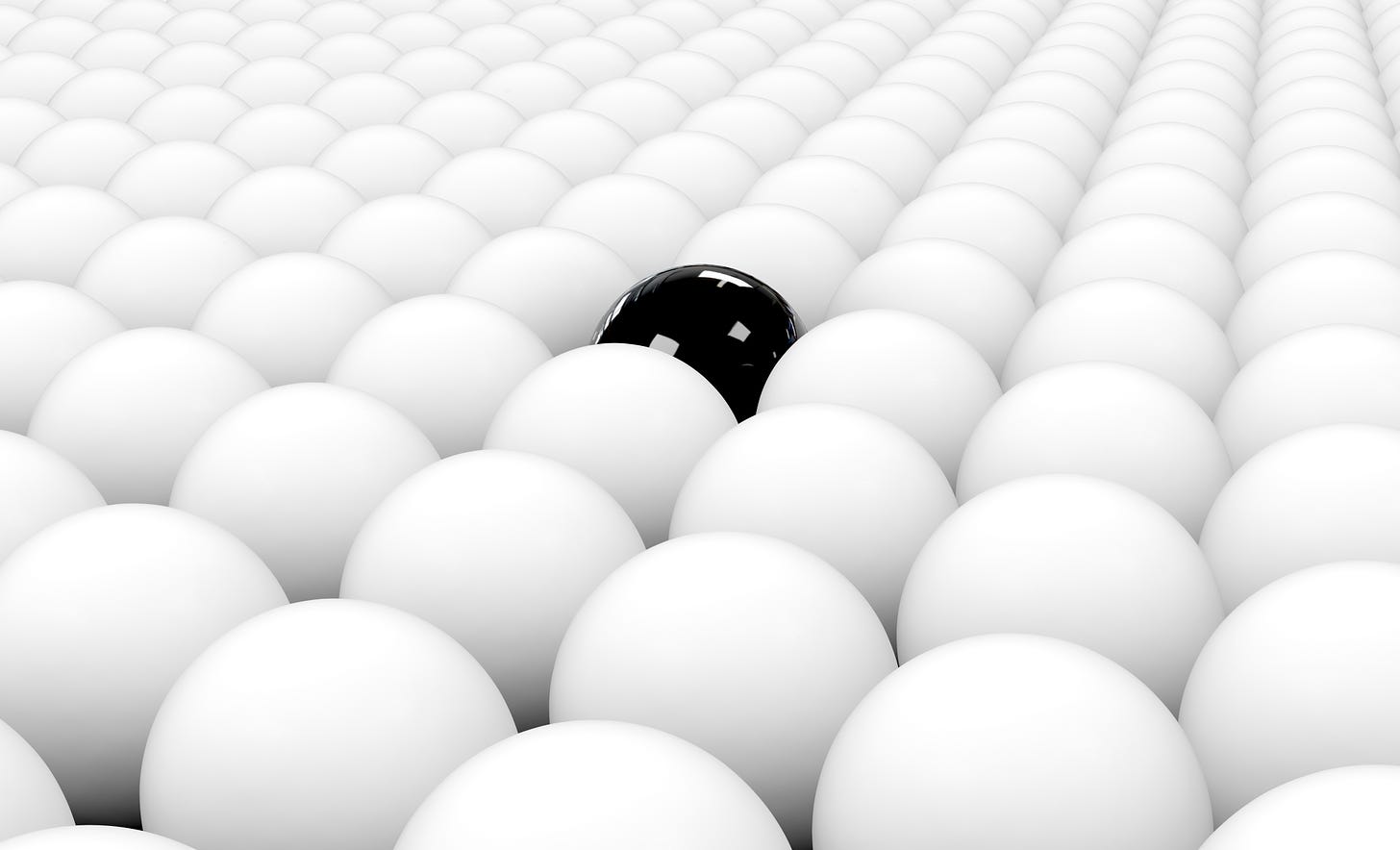

Black Balls

One way of looking at human creativity is as a process of pulling balls out of a giant urn. The balls represent possible ideas, discoveries, technological inventions. Over the course of history, we have extracted a great many balls— mostly white (beneficial) but also various shades of gray (moderately harmful ones and mixed blessings). The cumulative effect on the human condition has so far been overwhelmingly positive, and may be much better still in the future.

What we haven’t extracted, so far, is a black ball: a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it. The reason is not that we have been particularly careful or wise in our technology policy. We have just been lucky.

—Nick Bostrom, “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis”

Let’s borrow Bostrom’s scheme and adapt it as so:

Light balls

- White balls—beneficial ideas

- Light grey balls—mixed blessing (dual-use) ideas

Dark balls

- Dark grey balls—moderately harmful (e.g. a new scamming method)

- Black balls—truly pernicious species-altering or -ending ideas (Bostrom gives the example of “easy nukes” in his paper: suppose it became relatively trivial and cheap for a small group of adults to build a nuclear bomb)

There are two primary questions then:

- Would the JoDI increase the overall amount of harm done from dark balls?

- Would the JoDI increase the total benefit from drawing white balls enough to offset any increased levels of harm from dark balls?

In regards to the first question, it seems likely that the JoDI would, simply by virtue of its existence, inspire us to grab more dark balls from the urn. But for these balls to cause harm, they must “fall into the wrong hands”, so to speak. It seems plausible to that the JoDI could cause a drop in the rate of dark balls grabbed or possessed by bad actors because more good actors will be reaching for dark balls (assuming large numbers of people are aware of the JoDI and attempting to publish in it). While too much oversight defeats the entire purpose of the journal, it might make sense to have some kind of initial screening process whereby sufficiently dangerous black balls can be kept under wraps and routed to the appropriate authorities/experts. This screening process presents its own serious concerns and questions (who watches the watchers?), but it should still increase the chances that a black ball is pulled in the safest possible manner. For lighter and less dangerous orbs, publication can obviate the idea’s element of surprise and give us a head start on developing new safety or security technologies, regulations, counter-arguments, cultural movements, etc.

White Balls

H. P. Lovecraft, writing to Edwin Baird, the first editor of Weird Tales:

Popular authors do not and apparently cannot appreciate the fact that true art is obtainable only by rejecting normality and conventionality in toto, and approaching a theme purged utterly of any usual or preconceived point of view. Wild and “different” as they may consider their quasi-weird products, it remains a fact that the bizarrerie is on the surface alone; and that basically they reiterate the same old conventional values and motives and perspectives. Good and evil, teleological illusion, sugary sentiment, anthropocentric psychology—the usual superficial stock in trade, and all shot through with the eternal and inescapable commonplace….

Whoever wrote a story from the point of view that man is a blemish on the cosmos, who ought to be eradicated? As an example—a young man I know lately told me that he means to write a story about a scientist who wishes to dominate the earth, and who to accomplish his ends trains and overdevelops germs…and leads armies of them in the manner of the Egyptian plagues. I told him that although this theme has promise, it is made utterly commonplace by assigning the scientist a normal motive. There is nothing outré about wanting to conquer the earth; Alexander, Napoleon, and Wilhelm II wanted to do that. Instead, I told my friend, he should conceive a man with a morbid, frantic, shuddering hatred of the life-principle itself, who wishes to extirpate from the planet every trace of biological organism, animal and vegetable alike, including himself. That would be tolerably original. But after all, originality lies with the author. One can’t write a weird story of real power without perfect psychological detachment from the human scene, and a magic prism of imagination which suffuses theme and style alike with that grotesquerie and disquieting distortion characteristic of morbid vision. Only a cynic can create horror—for behind every masterpiece of the sort must reside a driving demonic force that despises the human race and its illusions, and longs to pull them to pieces and mock them.

Lovecraft’s argument for the novelty of a truly pessimistic perspective also applies to the general pursuit of ideas: all of human thought and activity is tilted towards goodness—towards pleasure, happiness, flourishing, sunshine, rainbows, kittens; we rarely, if ever, gaze into the abyss in a sustained and systematic manner; the black forests and swamps of the landscape of ideas are under-explored; we sometimes stumble upon detrimental ideas in the happy valleys and sunny meadows of idea-land, so it would stand to reason that we might also stumble upon the most wondrous and beneficent ideas while exploring darker terrain; if “the road to hell is paved with good intentions”, then ipso facto the road to heaven is paved with bad intentions; QED.

ALL THE BALLS

Is The Journal of Dangerous Ideas a bad idea? Yeah, probably.

But we can’t know for sure. And what I do know for sure is that we didn’t get this far by playing it safe or playing scared.

We got this far by playing to WIN. We got this far by putting all of our SKIN IN THE GAME and playing for KEEPS. We got this far by going BALLS TO THE WALL and putting the PEDAL TO THE METAL.

So how do we want to go out?

Do we want to timidly grope around for white balls until we accidentally (but inevitably) grab a black ball? Or do we want to reach for ALL THE BALLS and go out in a BLAZE OF GLORY with our guns BLAZING?

Do we want to slowly fade away or rage against the dying of the light?

Do we want to go out like cowards or go wildly into that good night?

(To answer the obvious question: No, I do not have any current plans to actually found the JoDI, so if anyone is feeling sufficiently inspired, then by all means go for it. I’m happy to consult on the project and share the lessons I’ve learned from founding Seeds of Science.)

Further reading

- the aforementioned “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis” (Bostrom, 2019)

- Bostrom again (2011): “Information Hazards: A Typology of Potential Harms from Knowledge”

And two from me:

- 20 Modern Heresies (maybe not dangerous per se but definitely spicy)

- Ideas are Alive and You are Dead

I'm not sure if this is a good post (I didn't vote on it either way), but it seems like the sort of thing that would be far more likely to get a positive reception on April Fools Day than any other point.