(Crossposted from the MIRI blog)

Update Nov. 28: We’ve updated this post to announce that Haskell developer Edward Kmett has joined the MIRI team! Additionally, we’ve added links to some of our recent Agent Foundations research.

Our donors showed up in a big way for Giving Tuesday! Through Dec. 29, we’re also included in a matching opportunity by professional poker players Dan Smith, Aaron Merchak, Matt Ashton, and Stephen Chidwick, in partnership with Raising for Effective Giving. As part of their Double-Up Drive, they’ll be matching up to $200,000 to MIRI and REG. Donations can be made either on doubleupdrive.com, or by donating directly on MIRI’s website and sending your donation receipt to receipts@doubleupdrive.com. We recommend the latter, particularly for US tax residents (MIRI is a 501(c)(3) organization).

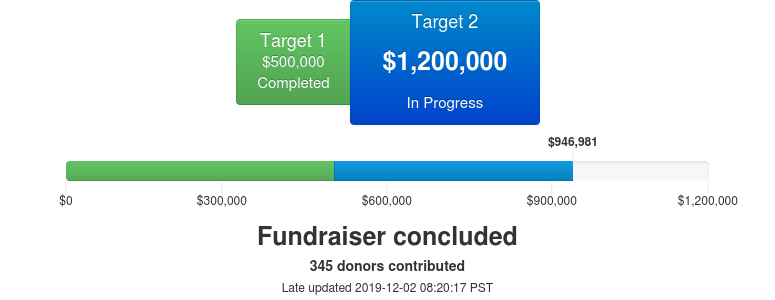

MIRI is running its 2018 fundraiser through December 31! Our progress:

MIRI is a math/CS research nonprofit with a mission of maximizing the potential humanitarian benefit of smarter-than-human artificial intelligence. You can learn more about the kind of work we do in “Ensuring Smarter-Than-Human Intelligence Has A Positive Outcome” and “Embedded Agency.”

Our funding targets this year are based on a goal of raising enough in 2018 to match our “business-as-usual” budget next year. We view “make enough each year to pay for the next year” as a good heuristic for MIRI, given that we’re a quickly growing nonprofit with a healthy level of reserves and a budget dominated by researcher salaries.

We focus on business-as-usual spending in order to factor out the (likely very large) cost of moving to new spaces in the next couple of years as we continue to grow, which introduces a high amount of variance to the model.[1]

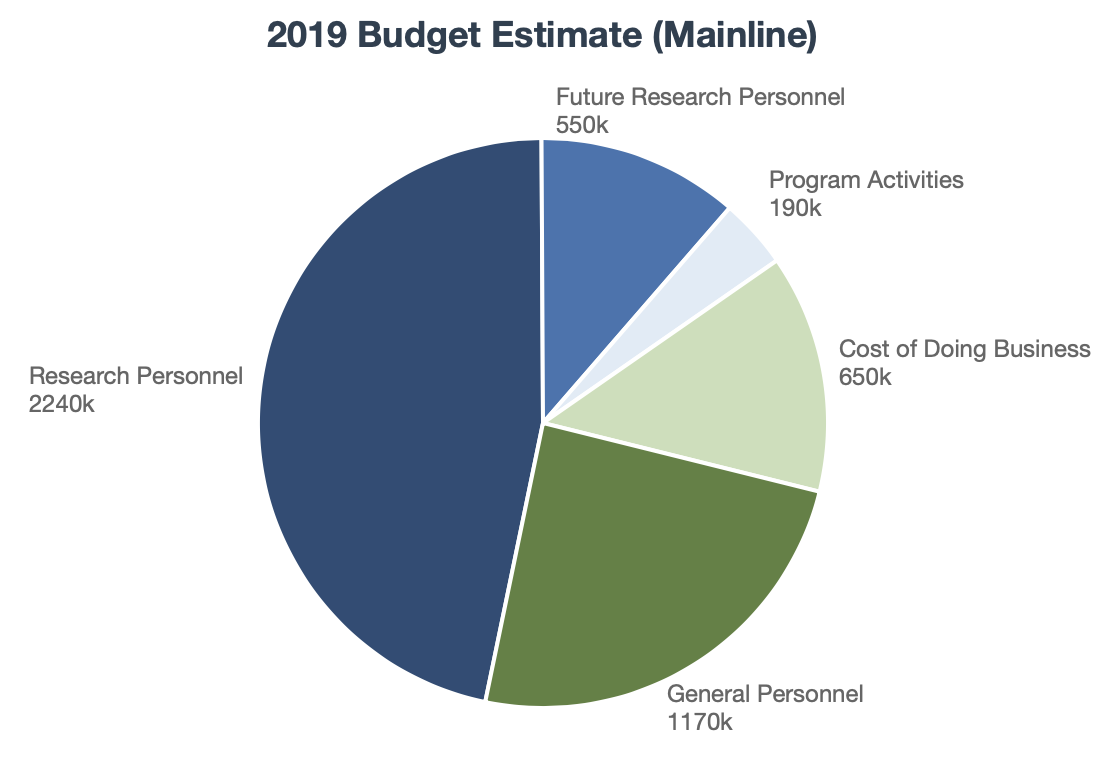

My current model for our (business-as-usual, outlier-free) 2019 spending ranges from $4.4M to $5.5M, with a point estimate of $4.8M—up from $3.5M this year and $2.1M in 2017. The model takes as input estimated ranges for all our major spending categories, but the overwhelming majority of the variance comes from the number of staff we’ll add to the team.[2]

In the mainline scenario, our 2019 budget breakdown looks roughly like this:

In this scenario, we currently have ~1.5 years of reserves on hand. Since we’ve raised ~$4.3M between Jan. 1 and Nov. 25,[3] our two targets are:

- Target 1 ($500k), representing the difference between what we’ve raised so far this year, and our point estimate for business-as-usual spending next year.

- Target 2 ($1.2M), what’s needed for our funding streams to keep pace with our growth toward the upper end of our projections.[4]

Below, we’ll summarize what’s new at MIRI and talk more about our room for more funding.

1. Recent updates

We’ve released a string of new posts on our recent activities and strategy:

- 2018 Update: Our New Research Directions discusses the new set of research directions we’ve been ramping up over the last two years, how they relate to our Agent Foundations research and our goal of “deconfusion,” and why we’ve adopted a “nondisclosed-by-default” policy for this research.

- Embedded Agency describes our Agent Foundations research agenda as different angles of attack on a single central difficulty: we don’t know how to characterize good reasoning and decision-making for agents embedded in their environment.

- Summer MIRI Updates discusses new hires, new donations and grants, and new programs we’ve been running to recruit researcher staff and grow the total pool of AI alignment researchers.

And, added Nov. 28:

- MIRI’s Newest Recruit: Edward Kmett announces our latest hire: noted Haskell developer Edward Kmett, who popularized the use of lenses for functional programming and maintains a large number of the libraries around the Haskell core libraries.

- 2017 in Review recaps our activities and donors’ support from last year.

Our 2018 Update also discusses the much wider pool of engineers and computer scientists we’re now trying to recruit, and the much larger total number of people we’re trying to add to the team in the near future:

We’re seeking anyone who can cause our “become less confused about AI alignment” work to go faster.

In practice, this means: people who natively think in math or code, who take seriously the problem of becoming less confused about AI alignment (quickly!), and who are generally capable. In particular, we’re looking for high-end Google programmer levels of capability; you don’t need a 1-in-a-million test score or a halo of destiny. You also don’t need a PhD, explicit ML background, or even prior research experience.

If the above might be you, and the idea of working at MIRI appeals to you, I suggest sending in a job application or shooting your questions at Buck Shlegeris, a researcher at MIRI who’s been helping with our recruiting.

We’re also hiring for Agent Foundations roles, though at a much slower pace. For those roles, we recommend interacting with us and other people hammering on AI alignment problems on Less Wrong and the AI Alignment Forum, or at local MIRIx groups. We then generally hire Agent Foundations researchers from people we’ve gotten to know through the above channels, visits, and events like the AI Summer Fellows program.

A great place to start developing intuitions for these problems is Scott Garrabrant’s recently released fixed point exercises, or various resources on the MIRI Research Guide. Some examples of recent public work on Agent Foundations / embedded agency include:

- Sam Eisenstat’s untrollable prior, explained in illustrated form by Abram Demski, shows that there is a Bayesian solution to one of the basic problems which motivated the development of non-Bayesianlogical uncertainty tools (culminating in logical induction). This informs our picture of what’s possible, and may lead to further progress in the direction of Bayesian logical uncertainty.

- Scott Garrabrant outlines a taxonomy of ways that Goodhart’s law can manifest.

- Sam’s logical inductor tiling result solves a version of the tiling problem for logically uncertain agents.

- Prisoners’ Dilemma with Costs to Modeling: A modified version of open-source prisoners’ dilemmas in which agents must pay resources in order to model each other.

- Logical Inductors Converge to Correlated Equilibria (Kinda): A game-theoretic analysis of logical inductors.

- New results in Asymptotic Decision Theory and When EDT=CDT, ADT Does Well represent incremental progress on understanding what’s possible with respect to learning the right counterfactuals.

These results are relatively small, compared to Nate’s forthcoming tiling agents paper or Evan Hubinger, Chris van Merwijk, Vladimir Mikulik, Joar Skalse, and Scott Garrabrant’s forthcoming “The Inner Alignment Problem.” However, they should give a good sense of some of the recent directions we’ve been pushing in with our Agent Foundations work.

2. Room for more funding

As noted above, the biggest sources of uncertainty in our 2018 budget estimates are about how many research staff we hire, and how much we spend on moving to new offices.

In our 2017 fundraiser, we set a goal of hiring 10 new research staff in 2018–2019. So far, we’re up two research staff, with enough promising candidates in the pipeline that I still consider 10 a doable (though ambitious) goal.

Following the amazing show of support we received from donors last year (and continuing into 2018), we had significantly more funds than we anticipated, and we found more ways to usefully spend it than we expected. In particular, we’ve been able to translate the “bonus” support we received in 2017 into broadening the scope of our recruiting efforts. As a consequence, our 2018 spending, which will come in at around $3.5M, actually matches the point estimate I gave in 2017 for our 2019 budget, rather than my prediction for 2018—a large step up from what I predicted, and an even larger step from last year’s budget of $2.1M.[5]

Our two fundraiser goals, Target 1 ($500k) and Target 2 ($1.2M), correspond to the budgetary needs we can easily predict and account for. Our 2018 went much better as a result of donors’ greatly increased support in 2017, and it’s possible that we’re in a similar situation today, though I’m not confident that this is the case.

Concretely, some ways that our decision-making changed as a result of the amazing support we saw were:

- We spent more on running all-expenses-paid AI Risk for Computer Scientists workshops. We ran the first such workshop in February, and saw a lot of value in it as a venue for people with relevant technical experience to start reasoning more about AI risk. Since then, we’ve run another seven events in 2018, with more planned for 2019.As hoped, these workshops have also generated interest in joining MIRI and other AI safety research teams. This has resulted in one full-time MIRI research staff hire, and on the order of ten candidates with good prospects of joining full-time in 2019, including two recent interns.

- We’ve been more consistently willing and able to pay competitive salaries for top technical talent. A special case of this is hiring relatively senior research staff like Edward Kmett.

- We raised salaries for some existing staff members. We have a very committed staff, and some staff at MIRI had previously asked for fairly low salaries in order to help keep MIRI’s organizational costs lower. The inconvenience this caused staff members doesn’t make much sense at our current organizational size, both in terms of our team’s productivity and in terms of their well-being.

- We ran a summer research internship program, on a larger scale than we otherwise would have.

- As we’ve considered options for new office space that can accommodate our expansion, we’ve been able to filter less on price relative to fit. We’ve also been able to spend more on renovations that we expect to produce a working environment where our researchers can do their work with fewer distractions or inconveniences.

2018 brought a positive update about our ability to cost-effectively convert surprise funding increases into (what look from our perspective like) very high-value actions, and the above list hopefully helps clarify what that can look like in practice. We can’t promise to be able to repeat that in 2019, given an overshoot in this fundraiser, but we have reason for optimism.

Donate now

- That is, our business-as-usual model tries to remove one-time outlier costs so that it’s easier to see what “the new normal” is in MIRI’s spending and think about our long-term growth curve.

- This estimation is fairly rough and uncertain. One weakness of this model is that it treats the inputs as though they were independent, which is not always the case. I also didn’t try to account for the fact that we’re likely to spend more in worlds where we see more fundraising success.

However, a sensitivity analysis on the final output showed that the overwhelming majority of the uncertainty in this estimate comes from how many research staff we hire, which matches my expectations and suggests that the model is doing a decent job of tracking the intuitively important variables. I also ended up with similar targets when I ran the numbers on our funding status in other ways and when I considered different funding scenarios. - This excludes earmarked funding for AI Impacts, an independent research group that’s institutionally housed at MIRI.

- We could also think in terms of a “Target 0.5” of $100k in order to hit the bottom of the range, $4.4M. However, I worried that a $100k target would be misleading given that we’re thinking in terms of a $4.4–5.5M budget.

- Quoting our 2017 fundraiser post: “If we succeed, our point estimate is that our 2018 budget will be $2.8M and our 2019 budget will be $3.5M, up from roughly $1.9M in 2017.” The $1.9M figure was an estimate from before 2017 had ended. We’ve now revised this figure to $2.1M, which happens to bring it in line with our 2016 point estimate for how much we’d spend in 2017.

Update: Added an announcement of our newest hire, Edward Kmett, as well as, a list of links to relatively recent work we've been doing in Agent Foundations, and updated the post to reflect the fact that Giving Tuesday is over (though our matching opportunity continues)!