Talk announcement: I will be presenting the arguments in this post and the post on (re)discovering natural laws on Tuesday 17 February at 18:00 GMT / 10:00 PT, as part of the closing of the Dovetail Fellowship. If you'd like to discuss these ideas live, you're welcome to join via this Zoom link. The session will be a 40-minute presentation followed by 20 minutes of Q&A.

BLUF: The Platonic Representation Hypothesis, the Natural Abstraction Hypothesis, and the Universality Hypothesis all claim that sufficiently capable AI systems will converge on a shared, objective model of reality, and that this convergence makes alignment more tractable. I argue that this conclusion does not follow, for four reasons:

- Reduction between physical theories is not clean (Section III). Even the textbook paradigm case, the reduction of thermodynamics to statistical mechanics, involves observer-relative choices (coarse-graining), additional empirical posits (the Past Hypothesis), and scope limitations. The "natural" abstractions these hypotheses invoke are not simply read off from the physics; they require substantive decisions that different observers could make differently.

- Physics is a patchwork of scale-dependent theories (Section IV). The limits connecting physical theories (classical to quantum, Newtonian to relativistic) are singular: they involve discontinuous changes in ontology, not smooth interpolation. There is no single unified description of reality from which all others derive. Different scales have autonomous effective ontologies with their own causal structures and explanatory frameworks. The convergence hypotheses assume precisely the unified reductive hierarchy that physics itself calls into question.

- Observation is not passive (Section V). Information gathering is a physical process that requires interaction, and every interaction has thermodynamic costs and scale-dependent constraints. There is no "view from nowhere": the data available to any observer is shaped by the mode and scale of its coupling to the world. Furthermore, all observation is theory-laden, presupposing theoretical and instrumental frameworks that determine what counts as a measurement and how results are interpreted. The datasets that train current AI systems are doubly mediated, by the physics of the instruments that captured them and by the choices about what was worth recording.

- The observed convergence in AI is better explained without strong metaphysics (Section VI). Current AI systems are all trained on artefacts of human culture at human scales (photographs, text, code). Their convergence reflects shared training distributions and shared inductive biases. Other attractor basins, corresponding to other scales and data sources, likely exist.

Even granting that environmental pressures exert strong inductive force on learned representations, these pressures are scale-dependent and observer-relative. What current AI systems are converging toward is not a conclusive set of representations of objects of reality but the statistical signature of the human-scale world as filtered through human instruments and theories.

I. Introduction

There is a pervasive optimism to be found in the interpretability and AI safety communities. It appears in John Wentworth's Natural Abstraction Hypothesis, in the Universality Hypothesis championed by the zoom in circuits crowd, and most explicitly in the Platonic Representation Hypothesis recently articulated by Huh et al. The core intuition is seductive: reality has a "natural" structure (or "a set of joints at which nature waits to be carved") and any sufficiently capable intelligence, driven by the convergent pressure of prediction, must eventually discover these same joints.

If this is right, the alignment problem becomes significantly more tractable. An AI's internal ontology[1] need not be an alien artefact of its architecture but a mirror of our own scientific understanding. Interpretability becomes a matter of reading off a shared map rather than translating between incommensurable conceptual schemes. Scaling need not produce alien representations; it should produce convergent ones.

I want to challenge this optimism. Not to dismiss it entirely, as the environment clearly exerts strong inductive pressure, and the convergence observed in current systems is real, but to argue that the story is considerably more complicated than it appears, and that the alignment conclusions drawn from it are premature.

My argument proceeds in four stages:

- Section II lays out the three convergence hypotheses and their alignment implications in detail, identifying the shared philosophical commitments (convergent realism, Nagelian reduction) that underpin them.

- Section III examines the philosophical case for reduction, focusing on the paradigm case of thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. I argue that even this best-case example involves observer-relative coarse-graining choices, additional empirical assumptions, and scope limitations that undermine the claim that "natural" abstractions are simply read off from the physics.

- Section IV zooms out to the structure of physical knowledge as a whole, arguing that the limits connecting different physical theories are singular, not smooth, and that physics is better understood as a patchwork of scale-dependent theories than as a reductive pyramid converging on a single fundamental description.

- Section V addresses the physics of observation itself, arguing that information gathering is always a physical interaction with associated costs, and that data is never a neutral reflection of reality but the product of theory-laden, scale-dependent coupling between observer and system.

- Section VI offers an alternative explanation for the observed convergence: current AI systems are converging toward a basin of attractors shaped by physical scale, data provenance, and shared inductive biases, and not toward the objective structure of reality.

- Section VII draws out the implications for alignment research.

The baseline is that what we observe is not convergence toward an objective "Platonic" reality, but convergence toward the statistical signature of the human-scale world. This is still important and worth studying, but it warrants considerably less metaphysical confidence than the convergence hypotheses suggest.

II. The Convergence Hypotheses

II.A. The Platonic Representation Hypothesis

Huh et al. (2024) state their position with remarkable directness:

"Neural networks, trained with different objectives on different data and modalities, are converging to a shared statistical model of reality in their representation spaces."

The philosophical commitment here is explicit. They frame their hypothesis as a modern instantiation of Platonic realism:

"Our central hypothesis is that there is indeed an endpoint to this convergence and a principle that drives it: different models are all trying to arrive at a representation of reality, meaning a representation of the joint distribution over events in the world that generate the data we observe."

This is not merely a claim about the behaviour of neural networks; it is a claim about the structure of reality itself, namely that there exists an objective "underlying reality" (which they denote ) of which our observations are "projections," and that sufficiently powerful learners will converge upon isomorphic statistical models of this reality. The claim is teleological[2]: convergence has an endpoint, and that endpoint is not arbitrary but latent in the structure of the world itself. Models are not merely finding useful compressions of their training data, but they are, in some meaningful sense, discovering the generative structure of reality, or at least, future models will do so.

Furthermore, the authors suggest this convergent representation may be uniquely identifiable:

"Additionally, this representation might be relatively simple, assuming that scientists are correct in suggesting that the fundamental laws of nature are indeed simple functions, in line with the simplicity bias hypothesis."

This is a strong metaphysical wager. It assumes not only that reality has a determinate structure waiting to be discovered, but that this structure is simple. It assumes that the joints at which nature waits to be carved are few, and that the inductive biases of neural networks (their preference for low complexity solutions) will guide them toward these joints rather than toward idiosyncratic artefacts of architecture or training distribution. The implicit claim is that simplicity bias is not merely a useful heuristic but is truth tracking.

Embedded in this view is a strong form of reductionism. The appeal to "fundamental laws of nature" as the basis for representational simplicity presupposes that higher level phenomena are in principle derivable from lower level descriptions. On this picture, there is a single unified from which all observations flow, and the task of representation learning is to recover this universal generative structure. The alignment implications from the Platonic Representation Hypothesis (PRH) follow naturally. If all sufficiently capable models converge toward the same representation of reality, then an AI's internal ontology need not (or indeed shall not) be opaque or incommensurable with our own. Interpretability becomes a matter of reading off a shared map rather than translating between fundamentally different conceptual schemes.

II.B. The Universality Hypothesis

The mechanistic interpretability community makes a related empirical bet. Olah et al. (2020) articulate the Universality Hypothesis (UH):

"Analogous features and circuits form across models and tasks."

They elaborate:

"It seems likely that many features and circuits are universal, forming across different neural networks trained on similar domains."

The hope is that interpretability research on one model transfers to others, that we are not chasing shadows unique to each architecture but uncovering something stable about how intelligence must represent the world.

The hypothesis matters because it determines what kind of research makes sense. As the authors put it:

"We introduced circuits as a kind of 'cellular biology of deep learning.' But imagine a world where every species had cells with a completely different set of organelles and proteins. Would it still make sense to study cells in general, or would we limit ourselves to the narrow study of a few kinds of particularly important species of cells? Similarly, imagine the study of anatomy in a world where every species of animal had a completely unrelated anatomy: would we seriously study anything other than humans and a couple domestic animals? In the same way, the universality hypothesis determines what form of circuits research makes sense."

The authors are careful to note that their evidence remains anecdotal:

"We have observed that a couple low level features seem to form across a variety of vision model architectures (including AlexNet, InceptionV1, InceptionV3, and residual networks) and in models trained on Places365 instead of ImageNet... These results have led us to suspect that the universality hypothesis is likely true, but further work will be needed to understand if the apparent universality of some low level vision features is the exception or the rule."

There are several reasons to be cautious about the strong interpretation of universality.

There is a selection effect in the evidence worth being cautious about. Researchers naturally notice and report the features that look similar across models. Edge detectors, curve detectors, and Gabor-like filters are visually recognisable and match our prior expectations from neuroscience. But what about the features that do not match? The Distill articles document numerous "polysemantic" neurons that respond to seemingly unrelated inputs (cat faces, car fronts, and cat legs in one documented case). These neurons are model-specific in their particular combinations. This does not by itself refute universality, as polysemanticity might be a compression artefact that disappears at scale, or it might yield to better analysis tools. But it does suggest that if we focus on the clean, interpretable features and set aside the messy polysemantic ones, we risk overstating the degree of universality. The picture may look tidier than it is because we are drawn to the cases that confirm our expectations.

The question is whether this convergence extends beyond low-level features with known-optimal solutions. Do models converge on "dog detector" or "tree detector" in the same way they converge on "edge detector"? Here the evidence is considerably thinner. Low-level features like edge and curve detectors have a strong mathematical claim to optimality: they are, roughly speaking, the solutions you would derive from first principles if you wanted to efficiently encode local image statistics. It is not surprising that different architectures converge on them, any more than it is surprising that different calculators agree on the value of pi. Higher-level features are more likely to be shaped by the statistics of the training data, the architectural details of the model, and the specific task being optimised. A model trained on ImageNet, which is heavily weighted toward certain categories of objects photographed from certain angles in certain contexts, may learn very different high-level features than a model trained on satellite imagery or medical scans or abstract art.

A defender of the convergence view will reasonably object that this misses the intended claim. The argument is not that any single narrow dataset produces convergent representations, but that convergence emerges in the limit: as you aggregate datasets, covering ImageNet and satellite imagery and medical scans and protein structures and everything else, training a sufficiently capable general-purpose system on all of it, the representations should converge. On this view, the lack of convergence we see with narrow datasets is simply a symptom of insufficient data diversity, not evidence against the hypothesis itself.

This is a serious objection, and I want to be careful not to dismiss it too quickly. It may well be that broader training distributions produce broader convergence across many human-relevant domains. But I think there are substantive reasons to doubt that this process terminates in a single unified representation of reality, reasons that go beyond the contingent limitations of current systems.

The first reason concerns the provenance of the data. Even a maximally diverse aggregation of datasets is not a neutral sample of "reality itself." Every dataset in the collection is the product of human instruments, human selection criteria, and human theoretical frameworks. Satellite imagery is captured by instruments designed according to our physical theories, at resolutions we chose, of regions we decided were interesting. Medical scans reflect the diagnostic categories of human medicine. Protein structure data comes from X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, techniques that impose their own constraints on what is observable. Aggregating all of these gives you a richer and more comprehensive picture of the world as accessed through human instrumentation, but it does not thereby give you unmediated access to the world's structure. You have expanded the basin, not escaped it. The dataset that aggregates "everything" is still everything-as-measured-by-us, which is a importantly different thing from everything-as-it-is. Section V develops this point in detail.

The second reason is more fundamental and concerns the structure of physical theory itself. If the effective theories governing different physical regimes are connected by singular limits rather than smooth interpolation, as I argue in Section IV, then there is no guarantee that more data from more scales produces a single coherent ontology. It might instead produce something closer to what we actually see in physics: a patchwork of representations that work well within each regime but resist unification into a single consistent picture. This is not a temporary embarrassment that will be resolved by more data or better architectures. It reflects something about the structure of physical knowledge itself. The history of physics is, among other things, a history of repeated failed attempts to achieve exactly the kind of unified representation that the convergence hypothesis posits.

I want to stress that neither of these points constitutes a knockdown refutation of the weak version of the convergence hypothesis. Strong convergence may well hold across a wide range of human-relevant scales and domains, and that would be both important and useful. The question is whether the evidence we currently have warrants the further conclusion: that this convergence reflects the discovery of objective, mind-independent structure rather than the structure of our particular epistemic situation.

And here the empirical evidence is simply not up to the task. The universality claim rests primarily on observations from vision models trained on natural images from datasets like ImageNet and Places365. These are all models trained on human photographs of macroscopic objects in human environments. That different architectures, when trained on this shared distribution, learn similar features is a genuinely interesting finding. But it is a finding about the interaction between neural network inductive biases and this particular data distribution. The leap from "different architectures converge when trained on similar data" to "all sufficiently capable intelligences will converge on the same representation of reality" is enormous, and the evidence does not come close to bridging it.

II.C. Natural Abstraction Hypothesis

Wentworth's Natural Abstraction Hypothesis tries to provide formal machinery for a similar intuition. In his 2025 update on the Natural Latents agenda, he articulates the "territory first" view explicitly:

"It doesn't matter if the observer is a human or a superintelligence or an alien, it doesn't matter if they have a radically different internal mind-architecture than we do; it is a property of the physical gas that those handful of parameters (energy, particle count, volume) summarize all the information which can actually be used to predict anything at all about the gas' motion after a relatively-short time passes."

And further:

"The key point about the gas example is that it doesn't talk much about any particular mind. It's a story about how a particular abstraction is natural (e.g. the energy of a gas), and that story mostly talks about properties of the physical system (e.g. chaotic dynamics wiping out all signal except the energy), and mostly does not talk about properties of a particular mind. Thus, 'territory-first'."

A terminological note is in order here, since Wentworth's work involves two distinct components that are easy to conflate. The Natural Abstraction Hypothesis (NAH) is the broad empirical and philosophical claim: that the physical world abstracts well, that the low-dimensional summaries relevant for prediction correspond to the high-level concepts humans use, and that a wide variety of cognitive architectures will converge on approximately the same abstractions. Natural latents are the specific mathematical formalism developed to make this precise. A natural latent is a latent variable satisfying two conditions: mediation (parts of the system are approximately independent given the latent) and redundancy (the latent can be recovered from any single part). The central theorem then shows that latents satisfying these conditions are stable across ontologies, meaning they are translatable between agents with different generative models of the same data. The mathematical results about natural latents are genuine contributions and not what I am challenging here. My target is the NAH: the philosophical claim that these natural latents correspond to objective, observer-independent features of reality and that any sufficiently capable intelligence will converge upon them. It is the step from "here is a well-defined mathematical property that certain latent variables can have" to "reality is structured such that the important latent variables will generically have this property" that carries the philosophical weight, and it is that step I want to interrogate.

The alignment implications of the NAH are drawn out in Natural Latents:

"When and why might a wide variety of minds in the same environment converge to use (approximately) the same concept internally? ...both the minimality and maximality conditions suggest that natural latents (when they exist) will often be convergently used by a variety of optimized systems."

This is a philosophically ambitious claim. But it is worth noting that it is not, strictly speaking, a new claim. The "territory first" framing recapitulates a position well established in the philosophy of science: convergent realism, as defended by Putnam (1960) and Boyd (1983). As the SEP entry on Scientific Realism summarises: "The idea that with the development of the sciences over time, theories are converging on ('moving in the direction of', 'getting closer to') the truth, is a common theme in realist discussions of theory change."

The structure of the argument is identical. Convergent realism holds that (i) there is a determinate, mind independent world; (ii) scientific theories are approximately true descriptions of this world; and (iii) the progress of science asymptotically converges on a true account. The Natural Abstraction Hypothesis transposes this into the language of information theory and Bayesian agents: (i) there is a determinate physical structure; (ii) natural latents are essentially complete correct summaries of this structure; and (iii) any sufficiently capable learner will converge on the same natural latents. The philosophical work is being done by the same assumptions. It is convergent realism with a change of vocabulary.

Similarly, the claim that natural latents are "stable across ontologies", or that they provide a translation layer between agents with different generative models, recapitulates the classical Nagelian account of intertheoretic reduction. Nagel (1961) argued that a theory T₂ reduces to a theory T₁ just in case the laws of T₂ are derivable from those of T₁ (plus bridge laws connecting their vocabularies). Wentworth's natural latents play exactly this role: they are the bridge laws that guarantee translatability. When Wentworth asks, "Under what conditions are scientific concepts guaranteed to carry over to the ontologies of new theories, like how e.g. general relativity has to reduce to Newtonian gravity in the appropriate limit?", he is asking the classical question of intertheoretic reduction, and answering it with the classical answer: reduction is possible when the higher level theory's vocabulary can be defined in terms of the lower level theory's vocabulary, mediated by natural latents rather than Nagel's bridge laws.

II.D. The Alignment Promise

If these hypotheses hold, the alignment problem becomes significantly more tractable. We could hope to identify "natural" concepts in neural networks that correspond to human legible categories, trust that scaling does not produce alien ontologies but converges toward familiar structure, build interpretability tools that generalise across architectures, and perhaps even hope for something like "alignment by default," where a sufficiently capable world model naturally develops an abstraction of human values simply by virtue of modelling the human world accurately, making the remaining alignment work a matter of identifying and leveraging that internal representation rather than constructing one from scratch.

This post is an interrogation of that optimism.

To understand what these convergence claims are actually asserting, we need to trace their intellectual lineage. The PRH, the UH, and NAH are making broad metaphysical claims about the structure of reality and the conditions under which different observers must arrive at the same representations. These are, in essence, claims about reduction: about how descriptions at one level relate to descriptions at another, and whether there is a privileged "fundamental" description toward which all others converge. Philosophy of science has been grappling with exactly these questions for decades, and the lessons are instructive.

III. The Trouble with Reduction

III.A. The Nagelian Model and Its Failures

The Nagelian model of intertheoretic reduction holds that one theory reduces to another when the laws of the former can be logically derived from the latter, supplemented by bridge laws connecting their vocabularies. This picture has a certain elegance: if the derivation goes through, truth is preserved, and we can explain why the reduced theory worked so well. But the philosophical literature on reduction has, over the past sixty years, catalogued a series of difficulties that complicate this tidy picture considerably.

The first problem is that even in textbook cases, strict derivation fails. Schaffner (1967) and Sklar (1967) pointed out that Galileo's law of free fall (constant acceleration near Earth's surface) is strictly inconsistent with Newtonian gravitation, which implies acceleration varies with distance from Earth's centre. What Newton gives us is an approximation to Galileo, not Galileo itself. Nagel (1970) eventually conceded this, suggesting approximations could be folded into the auxiliary assumptions, but this weakens the deductive picture considerably. The SEP entry on intertheory relations notes that "at most, what can be derived from the reducing theory is an approximation to the reduced theory, and not the reduced theory itself."

More fundamental challenges came from Feyerabend (1962), who attacked the very idea that bridge laws could connect the vocabularies of successive theories. His incommensurability thesis held that scientific terms are globally infected by the theoretical context in which they function. "Mass" in Newton doesn't mean the same thing as "mass" in Einstein, and so purported identifications across theories become philosophically suspect. This is not to deny that there is something connecting "mass" across the two theories: they agree numerically in a wide range of cases and play analogous structural roles. But the similarity does not amount to identity. Newtonian mass is conserved, frame-independent, and additive. Relativistic mass (insofar as the concept is even used in modern physics, which it mostly isn't) is frame-dependent and not straightforwardly additive. Rest mass is Lorentz invariant but plays a different theoretical role than Newtonian mass does. The connection between these notions is real, but it is a relationship of partial overlap and approximate agreement within a regime, not the clean identity that Nagelian bridge laws require or that a single stable natural latent would imply. Kuhn developed similar ideas about meaning change across paradigm shifts. The SEP entry on incommensurability provides a thorough treatment of how both thinkers developed these critiques, and how they differ: Feyerabend located incommensurability in semantic change, while Kuhn's version encompassed methodological and observational differences as well.

Then there is multiple realisability. Sklar (1993) argues that thermodynamic temperature can be realised by radically different microphysical configurations: mean kinetic energy in an ideal gas, but something quite different in liquids, solids, radiation fields, or quantum systems. If a single macroscopic property can be instantiated by indefinitely many microscopic substrates, then no simple bridge law of the form "temperature = mean kinetic energy" will suffice. The reducing theory doesn't give us a unique correspondent for each term in the reduced theory. Batterman (2000) develops related arguments in the context of universality in statistical field theory, the phenomenon whereby radically different physical systems exhibit identical statistical behaviour near critical phase transitions.

III.B. The Paradigm Case: Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics

These general problems become especially acute in the case most often cited as the paradigm of successful reduction: thermodynamics to statistical mechanics. Wentworth's Natural Abstraction Hypothesis leans heavily on this example, treating the ideal gas as the canonical instance of natural latents, where macroscopic variables like energy, volume, and particle number that supposedly summarise all predictively relevant information about a system's future. The claim is that these variables are properties of the physical system itself, not of any particular mind, and that any sufficiently capable observer would converge on them.

This is a strong claim, and the ideal gas is the best case for it. If the "territory first" view cannot be sustained even here, it is difficult to see how it could be sustained in general. I want to argue that it cannot, for a specific reason: getting from the microphysics to the macroscopic variables that Wentworth treats as "natural" requires a series of substantive choices and assumptions that are not dictated by the physics itself. Each of the well-known philosophical difficulties with this reduction illustrates a different way in which observer-relative decisions enter the picture.

1.Coarse-graining is not unique

The most direct challenge to the "territory first" view comes from the very definition of entropy in statistical mechanics. Boltzmann entropy counts the number of microstates compatible with a given macrostate. But classical phase space is continuous; there are uncountably many microstates. To get a finite count, one must coarse- grain: partition phase space into cells and count cells rather than points. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes that "since the values of and p can be chosen arbitrarily, the entropy is not uniquely defined." This matters directly for the NAH, because the macroscopic variables that emerge (the supposedly "natural" abstractions) depend on how the coarse-graining is performed. Different partitions of phase space yield different macrostates and therefore different candidate abstractions. The choice of coarse-graining is not given by the microphysics; it is imposed from outside, and different observers with different interests or instruments could in principle impose different ones.

This point can be seen by looking at the difference between Boltzmann and Gibbs entropy. The Gibbs fine-grained entropy is computed from the exact probability distribution over phase space and is constant under Hamiltonian evolution by Liouville's theorem. Only the coarse-grained entropy increases. Entropy growth is thus not a feature of the dynamics themselves but an artefact of our chosen level of description. If the central quantity of thermodynamics depends on a choice that is not dictated by the physics, then the macroscopic theory cannot be straightforwardly "read off" from the microscopic one, which is precisely what the territory-first view claims.

2. The arrow of time requires an additional posit

Even granting a particular coarse-graining, there is the question of why entropy increases toward the future rather than the past. The underlying classical dynamics are time-reversal symmetric: for any trajectory along which entropy increases, there exists a time-reversed trajectory along which it decreases. Statistical mechanics cannot derive strict irreversibility from reversible microdynamics; it can only explain why entropy increase is overwhelmingly probable. The Second Law becomes a statistical generalisation rather than a necessary truth. As the SEP's entry on statistical mechanics puts it:

"The thermodynamic principles demand a world in which physical processes are asymmetric in time. Entropy of an isolated system may increase spontaneously into the future but not into the past. But the dynamical laws governing the motion of the micro-constituents are, at least on the standard views of those laws as being the usual laws of classical or quantum dynamics, time reversal invariant."

Poincaré's recurrence theorem compounds the difficulty. Any bounded Hamiltonian system will, given enough time, return arbitrarily close to its initial state. Zermelo weaponised this against Boltzmann: if a gas eventually returns to its initial low-entropy configuration, entropy cannot increase forever. Boltzmann's response was pragmatic rather than principled (recurrence times are astronomically long, far exceeding any observation timescale), but this concedes that the Second Law is not strictly derivable from mechanics.

To explain the temporal asymmetry, contemporary Boltzmannian approaches require a cosmological boundary condition: the universe began in an extraordinarily low-entropy state. Albert (2000) calls the resulting probabilistic framework the "Mentaculus." But this Past Hypothesis is not derived from statistical mechanics; it is an additional empirical posit about initial conditions. And Earman (2006) has argued that in general relativistic cosmologies, there may be no well-defined sense in which the early universe's Boltzmann entropy was low; the hypothesis may be, in his memorable phrase, "not even false." The relevance for the NAH is that the macroscopic behaviour Wentworth treats as flowing from the system's intrinsic properties in fact depends on a cosmological assumption about the boundary conditions of the entire universe. The "natural" abstractions are not self-contained properties of the gas; they require external input about the state of the cosmos to do their explanatory work.

3. The paradigm case has limited scope

Uffink (2007) emphasises that the standard combinatorial argument for equilibrium (showing that the Maxwell- Boltzmann distribution maximises the number of compatible microstates) assumes non-interacting particles. This works tolerably for dilute gases but fails for liquids, solids, and strongly interacting systems. Yet thermodynamics applies perfectly well to all of these. The bridge between statistical mechanics and thermodynamics depends on special conditions, like weak interactions, large particle numbers, and particular initial conditions, that are not always met. If the "natural" abstractions only emerge under these special conditions, they are less natural than advertised: they are properties of a particular class of systems under particular idealisations.

4. The same abstraction has no single microphysical basis

Finally, there is the multiple realisability problem in concrete form. A gas of molecules and a gas of photons both have well-defined temperatures, pressures, and entropies, but their microscopic constituents are utterly different: massive particles versus massless bosons. There is no single microphysical property that "temperature" reduces to across all thermodynamic systems. For the NAH, this creates a tension. If "temperature" is a natural latent, what is it a latent of? It cannot be mean kinetic energy, because that identification fails for radiation. It cannot be any single microphysical property, because the microphysical realisers differ across systems. The abstraction is stable at the macroscopic level, but it does not correspond to a unique structure at the microscopic level. This is consistent with the view that temperature is a useful macro-scale summary rather than a joint at which nature is pre-carved.

What this means for the NAH

Wentworth uses the ideal gas as his paradigm case of "natural" abstractions that any observer would converge upon. But the philosophical literature suggests this case is considerably messier than advertised. The abstractions are not simply read off from the physics; they require substantive choices about coarse-graining scales, assumptions about initial conditions, limiting procedures (the thermodynamic limit ), and restrictions on the class of systems considered. Different choices could yield different "natural" variables. The gas example does not demonstrate that nature comes pre-labelled with observer-independent abstractions; it demonstrates that, with the right approximations, assumptions, and limiting procedures, we can construct useful macroscopic descriptions. That is a much weaker claim, and it is not obvious that it generalises beyond the special conditions of equilibrium statistical mechanics.

To recap, the territory-first view as put forward by Wentworth does not escape the well-known challenges to convergent realism and Nagelian reduction by restating them in information- theoretic terms. The question of whether coarse-graining is objective or observer-relative, of whether there is a unique "natural" level of description or a pluralism of scale-dependent theories, remains open. The Natural Abstraction Hypothesis does not resolve it so much as assume it away.

One might object that thermodynamics is a special case: a nineteenth-century theory with well-known conceptual peculiarities, perhaps not representative of physics as a whole. But the difficulties we have encountered are not confined to the relationship between statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. They recur, in different guises, across every major transition in physics. To see this, it helps to step back and look at the structure of physical knowledge as a whole.

IV. Physics as a Patchwork of Scale-Dependent Theories

IV.A. The Cube of Physics

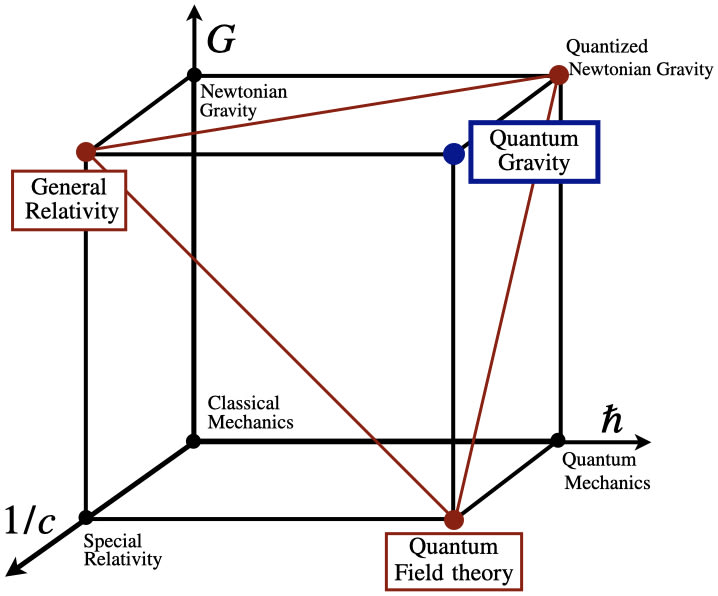

The hope that there is a single "natural" representation that any observer must converge upon ignores what physics itself teaches us about the structure of physical knowledge. Modern physics is not a single unified theory but a collection of models, each accurate within certain regimes of scale.

The cube of physics is a map which helps us to navigate the conceptual landscape of physical theories. The main idea is to make sense of this landscape by talking about the following fundamental constants:

- The speed of light , which encodes an upper speed limit for all physical processes.

- The gravitational constant , which encodes the strength of gravitational interactions.

- The (reduced) Planck constant , which encodes the magnitude of quantum effects.

Each corner of the cube represents a different physical theory, valid in a different regime. Classical Mechanics lives where we can ignore relativistic effects (), quantum effects (), and gravitational effects (). Special Relativity incorporates finite . Quantum Mechanics incorporates finite . General Relativity incorporates finite and . Quantum Field Theory combines quantum and special relativistic effects. And at the corner where all three constants are finite, we would need a theory of Quantum Gravity that we do not yet possess.

The cube is a useful pedagogical device, but it is thus a simplification that obscures important complications. The edges of the cube suggest smooth, well defined limits connecting one theory to another. In reality, these limits are far more treacherous than they appear.

IV.B. The Newtonian Limit of General Relativity

Consider the "Newtonian limit" of General Relativity. The standard story is that as (or equivalently, as velocities become small compared to the speed of light and gravitational fields become weak), the equations of General Relativity reduce to those of Newtonian gravity. But what does it mean to let the speed of light, a fundamental constant, "go to infinity"? This is conceptually peculiar: is not a parameter we can vary but a feature of the structure of spacetime itself. As Nickles (1973) pointed out in one of the first philosophical discussions of this limiting relation, what is the significance of letting a constant vary, and how is such variation to be interpreted physically?

But the problems run deeper than interpretation. Newtonian spacetime has a fundamentally different structure from relativistic spacetime. In General Relativity, spacetime is a four-dimensional Lorentzian manifold equipped with a single non-degenerate metric tensor of signature , which determines both spatial and temporal distances and encodes the causal structure in the light cones. In Newton-Cartan theory, this single object is replaced by two separate degenerate structures: a temporal 1-form that defines surfaces of absolute simultaneity, and a symmetric contravariant spatial metric of rank 3 that measures distances within those surfaces, subject to the compatibility condition . These two structures cannot be combined into a single non-degenerate metric. The limit does not smoothly deform one structure into the other; it involves the non-degenerate Lorentzian metric degenerating into the pair , a discontinuous change in which the light cones "open up" to become horizontal planes of simultaneity.

To make the limiting relationship mathematically precise, physicists have developed Newton-Cartan theory, a geometric reformulation of Newtonian gravity first introduced by Élie Cartan. In this formulation, Newtonian gravity is recast in the language of differential geometry, with gravity appearing as spacetime curvature encoded in a connection rather than as a force. The degenerate metric structure described above is precisely the geometry that this formulation requires. Newton-Cartan theory was constructed, in part, so that a rigorous sense could be given to the claim that Newtonian spacetimes are "limits" of general relativistic ones. But this is revealing in itself: a new theoretical framework had to be built to make the limit well-defined.

But the crucial point is that Newton-Cartan theory is not the same as Newton's original theory. It involves philosophical and mathematical assumptions that Newton never made and that are not present in the standard formulation of Newtonian mechanics. Newton-Cartan theory requires a four dimensional manifold structure, a degenerate temporal metric, a separate spatial metric, specific compatibility conditions between these structures, and a connection that encodes the gravitational field geometrically. None of this machinery appears in Newton's Principia. Newton conceived of gravity as a force acting instantaneously across absolute space; the geometrisation of this into spacetime curvature is a retrofitting that makes the theory look more like General Relativity precisely so that a limit can be defined.

So to show that General Relativity "reduces to" Newtonian gravity, we must first reformulate Newtonian gravity in a way that it was never originally formulated. The target of the reduction is not Newton's theory but a geometrised version of it constructed specifically to be the endpoint of a limiting procedure. This raises obvious questions about what "reduction" means in this context. Are we showing that GR reduces to Newtonian mechanics, or are we constructing a new theory (Newton-Cartan theory) that interpolates between them?

Furthermore, even with Newton-Cartan theory in hand, the limit is not straightforward. As Fletcher (2019) has shown, making the Newtonian limit rigorous requires careful attention to the topology one places on the space of spacetime models. Different choices of topology correspond to different classes of observables that one demands be well approximated in the limit. The question "does GR reduce to Newtonian gravity?" does not have a unique answer; it depends on what quantities you care about preserving.

IV.C. The Classical Limit of Quantum Mechanics

Similar problems arise with the quantum to classical transition. The relationship between quantum mechanics and classical mechanics as ℏ → 0 is notoriously problematic. The classical limit is singular: quantum interference effects do not smoothly disappear as ℏ decreases. Instead, they become increasingly rapid oscillations that require careful averaging or coarse-graining procedures to eliminate. The Wigner function, which provides a phase space representation of quantum states, develops finer and finer oscillatory structure as ℏ → 0, and only upon appropriate averaging does it approach a classical probability distribution.

The semi-classical regime, where ℏ is small but nonzero, exhibits phenomena that belong to neither the quantum nor the classical theory proper. Quantum tunneling persists at any finite ℏ, no matter how small. The behaviour near classical turning points (where a classical particle would reverse direction) involves Airy functions and other special structures that have no classical analogue. The WKB approximation, which provides the standard bridge between quantum and classical mechanics, breaks down precisely at these turning points, requiring "connection formulas" that patch together different approximations in different regions.

Many physicists point to decoherence as resolving the quantum-to-classical transition. Decoherence is real and well understood: when a quantum system becomes entangled with a large number of environmental degrees of freedom, interference effects become unobservable, and the system appears to behave like a classical statistical mixture. But as Adler (2003) and Schlosshauer (2004) argue, this appearance is not the same as a genuine reduction. Decoherence explains why interference terms vanish in practice, but it does not explain why one particular outcome occurs rather than another; the underlying quantum state remains a superposition (see the SEP entry on decoherence for a thorough treatment). More importantly for our purposes, decoherence requires a split between "system" and "environment" that is not given by the fundamental theory. Where one draws this boundary affects which states are selected as robust "pointer states." For macroscopic objects in typical terrestrial environments, there is usually an obvious choice, but the choice is not determined by the Schrödinger equation alone. It is imposed from outside, based on our interests and our coarse-grained description of the world. This is the same pattern we saw in the thermodynamic case: the "natural" classical description emerges only given a particular observer-relative decomposition of the total system.

IV.D. Batterman and the Asymptotic Borderlands

Robert Batterman, in his book The Devil in the Details, has made these points systematically. He argues that the limits connecting physical theories are typically singular limits, and that the behaviour in the neighbourhood of these limits often requires explanatory resources that neither the "fundamental" nor the "emergent" theory can provide on its own.

Consider the relationship between wave optics and ray optics. As the wavelength , wave optics should reduce to ray optics. But at finite small wavelength, one observes caustics: regions where the intensity of light becomes very high, associated with the focusing of rays. These caustic structures are not part of ray optics (which predicts infinite intensity at these points) nor are they straightforwardly derivable from wave optics (which requires asymptotic analysis to extract them). As the physicist Berry (1995), whom Batterman quotes extensively, puts it: the patterns "inhabit the borderland between the ray and wave theories, because when is zero the fringes are too small to see, whereas when is too large the overall structure of the pattern cannot be discerned: they are wave fringes decorating ray singularities."

Batterman's point is that these "asymptotic borderlands" are not merely technical curiosities. They are where much of the interesting physics lives, and they require what he calls "asymptotic reasoning" to understand: methods that are irreducibly approximate, that rely on the interplay between theories rather than the derivation of one from another. The dream of smooth reduction, where the emergent theory is simply a limiting case of the fundamental theory, fails in precisely the cases that matter most.

But the framework that explains universality, the renormalisation group, is itself a coarse-graining procedure, and it involves the same kind of substantive methodological choices we encountered in the thermodynamic case. One must decide on a blocking scheme (how to group microscopic degrees of freedom into effective variables), a cutoff scale (where to draw the line between "short-distance" and "long-distance"), which degrees of freedom to integrate out, and what order of truncation to impose on the effective action. Different blocking schemes can yield different RG flows. The identification of which operators count as "relevant" versus "irrelevant" depends on which fixed point one is flowing toward, something that is not known in advance but is determined by the coarse-graining choices one has already made. The universality of the resulting fixed point is robust across different microscopic starting points, but it is not robust across arbitrary coarse-graining procedures. The "natural" structure emerges only given a particular class of methodological choices that are not themselves dictated by the microphysics. This means that universality, instead of being a counterexample to the patchwork picture, is its purest illustration.

IV.E. Implications for Convergence

This has direct implications for the convergence hypotheses we have been examining. If theories do not reduce cleanly to one another, but are related by singular limits with autonomous "borderland" phenomena, then there is no reason to expect that representations learned at one scale will transfer smoothly to another. A system that learns to represent the world in terms of ray optics will not, by taking a smooth limit, arrive at wave optical representations. It will instead encounter a regime where neither representation is adequate and new concepts (caustics, Airy functions, the Maslov index) are required.

The point I want to draw from this is that these scale-dependent theories are not obviously mere approximations to some "true" underlying theory. There is a credible case that each regime has its own effective ontology, its own causal structure, its own explanatory framework, and that a solid theoretical understanding at one corner does not automatically translate to others (for a more detailed treatment of this perspective, see Some Perspectives on the Discipline of Physics).

The PRH's claim that there exists a single unified from which all observations flow, and that sufficiently powerful learners will converge upon it, assumes precisely what the structure of physics calls into question. The possibility that reality might be better described by a patchwork of scale dependent theories, each with its own effective ontology, is set aside. But physics itself suggests that this patchwork is not a temporary state of incomplete knowledge; it may be fundamental to how physical theories work.

Yet, there is an even deeper issue lurking here. The convergence hypotheses imagine observers as standing outside the physical world, passively receiving information about its structure. But observers are not outside the world; they are embedded in it. To learn anything about a physical system, an observer must interact with it, and interaction is a physical process governed by the same scale dependent physics we have been discussing. The "natural" representations are not those that carve reality at its joints, but those that match the scale and mode of the observer's coupling to the world. The next section examines this embedding in detail.

V. The Physics of Observation

We intuitively lean on the idea that certain world models (like Newtonian mechanics) are "natural." But where does this naturalness come from? It is not a property inherent to the "raw" microstates of the universe. Two distinct considerations suggest that the apparent naturalness of our representations is neither inevitable nor observer-independent.

V.A. The Physical Cost of Information

The scale dependence of physics has a direct consequence for any epistemic agent: the information available to an observer depends on the scale at which it interacts with the world. There is no such thing as information gathering without physical interaction. Any measurement requires a mechanism that couples the observer to the observed, and this coupling inherently requires an exchange of energy. A thermometer cannot learn the warmth of a bath without stealing some of its heat, infinitesimally altering the very state it seeks to record. To "know" the texture of a surface, a finger or sensor must press against it, deforming it; to "see" a distant star, a telescope must intercept photons that would otherwise have travelled elsewhere. Since every such interaction occurs at a particular energy scale and is governed by the effective physics of that scale, the data an observer gathers is not a neutral sample of "reality itself" but a reflection of the regime in which the observer operates. Data is never a disembodied "view from nowhere"; it is the product of a scale-dependent coupling between observer and world. This remains true even when the agent receiving the data is not the one that gathered it. A large language model trained on text, or a vision model trained on photographs, may appear to be learning from a static dataset that arrives "from nowhere." But that dataset was produced by cameras, thermometers, particle detectors, etc., all of which operate at particular energy scales and are governed by the effective physics of those scales. The scale-dependence is baked into the data before the model ever sees it.

In classical physics, we often treat observation as passive. At macroscopic scales, this is a reliable approximation: the photon bouncing off a car does not alter its trajectory in any measurable way. But this passivity is the result of a separation of scales, not a fundamental feature of measurement. The energy required to observe the system is negligible compared to the system's own energy, and so we can act as if the observation had no effect. The quantum case does not introduce a new problem; it reveals a universal one. When the energy of the interaction is comparable to the energy of the system being observed, the approximation breaks down and the observer's coupling to the world can no longer be ignored.

This has an important implication. It means that there is no such thing as getting information "for free." Every bit of information that an agent possesses about its environment was obtained through some physical process that coupled the agent to that environment. The information had to be captured and stored, and this capturing and storing is itself a physical process with thermodynamic costs (this is also why Maxwell's demon cannot violate the second law). The agent is always, in principle, embedded in the system it is measuring. In macroscopic physics, we can justifiably ignore this embedding when the scales are sufficiently separated, but the embedding never disappears entirely. It is a fundamental constraint on what it means to be an epistemic agent in a physical world.

V.B. The Theory-Ladenness of Observation

But there is another point to be made. Observations are not merely physical events; they are theoretical acts that always take place within a certain frame. As philosophers of science since Hanson (1958) and Kuhn (1962) have emphasized, every measurement presupposes a theoretical context that determines what counts as a measurement, what the relevant variables are, and how the results should be interpreted. There is no theory-neutral observation.

Consider quantum field theory. Our knowledge of QFT does not come from passively observing the quantum vacuum. It does not even come, in the first instance, from experiment. The Standard Model was constructed largely by postulating symmetries (like gauge invariance, Lorentz invariance, and local conservation laws) and working out their consequences. Experimental confirmation came later, often much later, and required apparatus that could only have been designed by people who already knew what they were looking for. The Higgs boson was not discovered by building a 27-kilometre ring of superconducting magnets and seeing what turned up. The LHC was built, in part, because the Standard Model predicted the (until then unobserved) Higgs boson; the collisions were run at 13 TeV because that was the energy regime where the theory said to look; and the decay products were analysed according to the predictions of a framework that had been developed decades earlier. There is no plausible history in which we build the LHC without already mostly knowing the answers. The observation is not merely inseparable from the theoretical framework within which it occurs, because the theoretical framework is what called the observation into existence in the first place.

This is not a defect of particle physics; it is a general feature of all observation. What follows from this for the question of "natural" representations? It means that datasets are always selected and curated. There is nothing purely objective about any dataset, as there are always choices made about what to measure and how, what instruments to use, what theoretical framework to employ, what counts as signal and what counts as noise. These choices are not arbitrary because they are constrained by what works, but they are also not uniquely determined by "reality itself." Different choices, reflecting different theoretical commitments and different practical purposes, could yield different datasets.

The data that trains our AI systems is therefore doubly theory-laden. It is theory-laden at the level of collection: a camera captures electromagnetic radiation in the narrow band of wavelengths that human eyes can see, at frame rates matched to human perception, at resolutions determined by our optical engineering. A microphone records pressure waves in the frequency range of human hearing. These are not neutral recording devices; they are instruments designed around human sensory capacities and built according to our physical theories. A civilisation with different sense organs or different theories might build very different instruments and produce very different datasets from the same physical world. The data is theory-laden a second time at the level of curation: what gets photographed, what gets written, what gets stored reflects human choices about what is interesting, valuable, or worth recording. The "convergence" that we observe in neural network representations is convergence on these doubly filtered datasets, not convergence on a theory-independent reality.

VI. Convergence to What?

The PRH, UH, and NAH posit that neural networks, as they scale, converge toward a shared, objective representation of reality, a "model of the world" that transcends specific architectures or training data. I want to argue that this "convergence" is better understood as convergence toward a shared statistical attractor than as discovery of an objective ontology.

VI.A. Why We Should Expect Convergence

To be clear: I do not dispute that convergence is occurring. I expect it, and I think we can explain why without invoking the PRH.

Consider what vision models and language models are actually trained on. Vision models see photographs, images captured by humans, of scenes humans found worth photographing, framed according to human aesthetic and practical conventions. Language models read text written by humans, about topics humans find interesting, structured according to human linguistic and conceptual categories. Both modalities are saturated with information about the same underlying subject matter: the human-scale world of objects, actions, and social relations that matter to us.

When a vision model learns to recognise cars, and a language model learns to predict text about cars, they are both extracting statistical regularities from data that was generated by humans interacting with cars. The car-concept that emerges in both models is not some Platonic form hovering in the abstract; it is the common structure present in how humans photograph, describe, and reason about cars. Given that both training distributions contain this shared structure, convergence is not surprising. It is the expected outcome.

This mundane explanation is reinforced by a further observation: the 'environments' used to train modern AI are not even independent in the way that would be needed to support the PRH's stronger claims. The PRH paper claims that different neural nets "largely converge on common internal representations," citing this as evidence for a universal structure. However, the datasets used (Common Crawl, Wikipedia, ImageNet, massive code repositories) are not diverse "environments" in any philosophically robust sense. They are different snapshots of the same statistical distribution: the human internet.

VI.B. The Basin of Attractors

Here is the alternative picture I want to propose. Neural network representations do converge, but toward a basin of attractors shaped by three factors.

The first is physical scale. The representations that emerge are appropriate to the scale of the data and the tasks. Macroscopic object categories, linguistic structures, and social concepts dominate because that is the scale at which human-generated training data exists. A model trained on ImageNet learns to represent dogs and chairs, not quarks and galaxies, because dogs and chairs are what ImageNet contains.

The second is data provenance. The convergence is toward the statistical regularities of human cultural production, not toward the objective structure of reality in itself. Our photographs are framed to highlight what humans find worth photographing, and our language is structured to describe our specific biological and social needs. When models align, they are finding the common denominator in how humans visually and linguistically categorise the world. This is convergence toward the statistical mean of the human perspective, because that is the only signal available in the training data.

The third factor is shared inductive biases. Neural architectures share certain biases (simplicity, smoothness, compositionality) that make them converge on similar solutions given similar inputs. These are properties of the learning algorithms, not of reality itself.

This explains why the Convergence Hypotheses seem compelling: there really is convergence, and it really is robust across architectures and modalities. But the convergence is toward a human-scale, human-generated, culturally mediated attractor basin, not toward the fundamental structure of reality.

The crucial point is that other basins likely exist. A model trained purely on quantum mechanical simulation data might converge toward representations incommensurable with macroscopic object categories. A model trained on cosmological data might develop ontologies organised around large-scale structure, dark matter distributions, and gravitational dynamics, concepts with no obvious counterpart in ImageNet. A model trained on the statistical patterns of protein folding might develop representations organised around energy landscapes and conformational dynamics that do not map onto human-legible categories.

Recall the natural response from Section II: that if we simply aggregate all these datasets, a sufficiently capable system trained on the lot would converge on a single unified representation. The arguments of Sections III through V give us reason to doubt this. If the effective theories governing these different regimes are connected by singular limits rather than smooth interpolation, there is no guarantee that representations learned at one scale combine neatly with those learned at another. And even the aggregated dataset remains the product of human instruments operating at particular scales, filtered through human theoretical frameworks. You have more coverage of the human-accessible world, but you have not escaped the human-accessible world. The convergence observed in current AI systems may simply reflect that we have trained them all on data from a single narrow band of scale and cultural origin. The PRH mistakes a local attractor for a global one.

VII. Implications for Alignment

If the basin of attractors picture is correct, several implications follow for alignment research.

Interpretability may not generalise as far as hoped. The structural motifs that interpretability researchers study (feature directions, circuits, polysemantic neurons) may well recur across architectures and scales; whether they do is a deep open question about the nature of neural network optimisation. But the specific features and circuits catalogued in current models, the particular concepts they represent, are products of training on human-scale, human-generated data. The evidence that these same features would appear in any sufficiently capable system is, as we have seen, considerably thinner than the convergence hypotheses suggest. What current interpretability research has established is that models trained on similar data develop similar representations. That is a useful and important finding, but it does not warrant the stronger conclusion that the interpretive frameworks we are building now will necessarily transfer to systems trained under substantially different conditions.

The implications for "alignment by default" are more nuanced than they might first appear. If current AI systems converge on human-legible representations because they are trained on human-scale data, then systems that continue to be trained this way may well continue to converge, and that convergence may be practically useful for alignment. But the justification for optimism shifts. It is no longer "these systems are discovering the objective structure of reality, so their ontologies will necessarily remain commensurable with ours," but rather "these systems are trained on human data, so their representations reflect human concepts." The former is a guarantee grounded in metaphysics; the latter is a contingent fact about training pipelines that could change. Alignment strategies that depend on representational convergence should be clear about which of these they are relying on, because the practical version offers considerably less assurance if and when training regimes change.

VIII. Conclusion and Future Directions

The Platonic Representation Hypothesis, the Natural Abstraction Hypothesis, and the Universality Hypothesis all share a common hope: that reality has a determinate structure, that intelligent systems will converge upon it, and that this convergence will make alignment tractable.

I have argued that this hope, while not baseless, rests on foundations that are considerably shakier than often acknowledged. The philosophical framework recapitulates convergent realism and Nagelian reduction, positions subject to extensive critique. The paradigm case of thermodynamics-to-statistical-mechanics reduction is far messier than advertised, involving substantive observer-relative choices. Physics itself suggests that different scales have autonomous effective ontologies connected by singular, non-smooth limits. And the apparent convergence of current AI systems may reflect shared training distributions and inductive biases rather than discovery of objective structure.

None of this means that convergent pressures are illusory, or that interpretability research is misguided. But it suggests we should be cautious about treating current empirical observations as evidence for strong metaphysical claims about the structure of reality or the absolute convergence of representations. It also means that these metaphysical claims should not serve as the primary motivation for interpretability research, since the convergence they point to may be an artefact of shared training conditions rather than a deep fact about intelligence. Interpretability research deserves better foundations than that. What we currently observe is convergence toward a basin of attractors, one shaped by human scales, human data, and human conceptual schemes. Other basins may exist, accessible to systems trained differently or operating at different scales.

The near-term path: specialised networks on curated data

If this picture is correct, it suggests a constructive path forward. If representations are shaped by training data and inductive biases, then we can deliberately choose data and architectures to push systems toward attractor basins corresponding to different scales and domains.

This is not merely a hypothetical. There is already a growing body of work demonstrating that neural networks can recover known physical laws when trained on appropriate data. Symbolic regression systems have rediscovered Newtonian mechanics from trajectory data. Graph neural networks have learned to simulate complex physical systems with remarkable accuracy. Neural networks have been used to identify conserved quantities and symmetries directly from raw observations, without being told what to look for. More striking still, we have been able to train networks to find regularities that were previously unknown. AlphaFold cracked the protein folding problem that had resisted solution for fifty years. Its success stems in part from its ability to draw on vastly more data than could otherwise be processed. It was able to find representations of the structure of energy landscapes and conformational dynamics that enabled it to predict protein folding. This suggests that appropriately designed networks, trained on carefully curated scientific data, can access attractor basins corresponding to genuine novel physical structure.

I believe that these specialised networks, trained on curated scientific datasets, will transform scientific practice in the near term more profoundly than general-purpose AI systems. The next major challenge is figuring out how to do this reliably across different areas of science: understanding which architectures and datasets and training regimes unlock which domains, and how to verify that the representations learned correspond to genuine structure. In a subsequent post, I describe these examples in more detail, and discuss some of the efforts made in automating the (re)discovery of natural laws in physics.

But there is an important limitation to notice here. AlphaFold, symbolic regression, and physics-informed neural networks all operate within the current paradigm: human researchers identify the domain, curate the dataset, design the architecture, and interpret the results. The system learns representations within a basin that the humans selected. The human is still in the loop, and the attractor basin is still, in a meaningful sense, human-chosen. The representations may be novel in their specifics, but they are novel within a framework that human scientific practice defined.

The harder question: escaping the basin

What would it take for a system to genuinely escape the human attractor basin? Not just to find new regularities within a human-curated dataset, but to discover entirely new theoretical frameworks at scales and in regimes that existing human data does not cover?

This would require something considerably more ambitious than learning from static datasets. A system would need to identify gaps in current theoretical understanding, design experiments or simulations to probe those gaps, gather and interpret the resulting data, and iteratively refine its representations based on what it discovers. This is, in effect, the full iterative loop of the construction of new scientific theories.

The crucial point is that this loop is itself a long-horizon coherent plan. It involves executing a sequence of steps over weeks or months, maintaining coherence across them, learning from intermediate results, and adjusting strategy accordingly. And this is precisely where current AI architectures hit a quantitative wall.

In a previous post on the economics of autonomous AI agents, I model this constraint quantitatively. The important crux is that current AI agents become unreliable on long tasks in a way that scaling does not fix. Larger models make fewer errors per step, but the structure of how errors compound over time appears to be an architectural property rather than a scaling property. The bottleneck is not capability per step but coherence across steps: current systems cannot learn from their own experience mid-task, and this limitation is not something that more parameters or more training data addresses.

This connects directly to the argument of this post. If current systems cannot maintain coherence over long-horizon plans, they cannot run the experimental loop that would be needed to access genuinely new attractor basins. They are confined to the basins defined by their static training data, which is to say, the basins that human researchers selected for them. The convergence we observe is not just a consequence of shared data in a philosophical sense; it is enforced by a concrete architectural limitation that prevents systems from gathering their own data at different scales.

What this means

The picture that emerges is, I think, more nuanced than either the convergence optimists or the most pessimistic alignment scenarios suggest. In the near term, current AI systems will continue to converge on human-legible representations, because they are trained on human data and confined to the human attractor basin by architectural limitations. This convergence is real and practically useful. Interpretability research that exploits it is valuable. Specialised networks trained on curated scientific data will push into new parts of this basin and may produce transformative results in specific domains.

In the longer term, the question of whether systems can access genuinely different attractor basins is gated on architectural breakthroughs, most likely some form of continual learning or an equivalent that enables coherent long-horizon autonomous operation. Whether we will have built adequate replacements by then is, I think, the question that matters most. And, it is a question that the convergence hypotheses, by encouraging complacency about the stability of current representations, may be making harder to take seriously.

Acknowledgments

This post was written by Margot Stakenborg. My background is in theoretical physics, chemistry, and philosophy of physics.

This work was funded by the Advanced Research + Invention Agency (ARIA) through project code MSAI-SE01-P005, as part of the Dovetail Fellowship.

Initial research was conducted during the SPAR winter programme.

Thanks also to Alex Altair, Alfred Harwood, Robert Adragna, Clara Torres Latorre,

Charles Renshaw-Whitman, and Daniel C for feedback and helpful conversations.

References

Adler, S. L. (2003). "Why Decoherence has not Solved the Measurement Problem: A Response to P.W. Anderson." Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 34(1), 135-142.

Albert, D. (2000). Time and Chance. Harvard University Press.

Batterman, R. (2000). "Multiple Realizability and Universality." British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 51(1): 115–145.

Batterman, R. (2002). The Devil in the Details: Asymptotic Reasoning in Explanation, Reduction, and Emergence. Oxford University Press.

Berry, M. (1995). "Asymptotics, singularities and the reduction of theories." Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics (Vol. 134, pp. 597-607). Elsevier.

Boyd, R. (1983). "On the Current Status of the Issue of Scientific Realism." Erkenntnis 19(1–3): 45–90.

Earman, J. (2006). "The 'Past Hypothesis': Not Even False." Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 37(3): 399–430.

Feyerabend, P. (1962). "Explanation, Reduction, and Empiricism." In Feigl & Maxwell (eds.), Scientific Explanation, Space, and Time. Minnesota Studies in Philosophy of Science 3.

Fletcher, S. C. (2019). "On the Reduction of General Relativity to Newtonian Gravitation." Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 68, 1-15.

Hanson, N. R. (1958). Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science. Cambridge University Press.

Huh, M., Cheung, B., Wang, T., & Isola, P. (2024). "The Platonic Representation Hypothesis." arXiv:2405.07987.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Nagel, E. (1961). The Structure of Science. Harcourt, Brace & World.

Nagel, E. (1970). "Issues in the Logic of Reductive Explanations." In Kiefer & Munitz (eds.), Mind, Science, and History.

Nickles, T. (1973). "Two Concepts of Intertheoretic Reduction." The Journal of Philosophy, 70(7), 181-201.

Olah, C., Cammarata, N., Schubert, L., Goh, G., Petrov, M., & Carter, S. (2020). "Zoom In: An Introduction to Circuits." Distill.

Schaffner, K. (1967). "Approaches to Reduction." Philosophy of Science 34(2): 137–147.

Schlosshauer, M. (2004). "Decoherence, the measurement problem, and interpretations of quantum mechanics." Reviews of Modern Physics, 76(4), 1267-1305.

Sklar, L. (1967). "Types of Inter-Theoretic Reduction." British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 18(2): 109–124.

Sklar, L. (1993). Physics and Chance: Philosophical Issues in the Foundations of Statistical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press.

Uffink, J. (2007). "Compendium of the Foundations of Classical Statistical Physics." In Butterfield & Earman (eds.), Handbook of the Philosophy of Physics.

Wentworth, J. (2025). "Natural Latents: Latent Variables Stable Across Ontologies" LessWrong.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries:

Philosophy of Statistical Mechanics

Intertheory Relations in Physics

The Incommensurability of Scientific Theories