All of Steven Byrnes's Comments + Replies

My gloss on this situation is:

YARROW: Boy, one would have to be a complete moron to think that COVID-19 would not be a big deal as late as Feb 28 2020, i.e. something that would imminently upend life-as-usual. At this point had China locked down long ago, and even Italy had started locking down. Cases in the USA were going up and up, especially when you correct for the (tiny) amount of testing they were doing. The prepper community had certainly noticed, and was out in force buying out masks and such. Many public health authorities were also sounding alarm...

OK, here’s the big picture of this discussion as I see it.

As someone who doesn’t think LLMs will scale to AGI, I skipped over pretty much all of your OP as off-topic from my perspective, until I got to the sentences:

...Eventually, there will be some AI paradigm beyond LLMs that is better at generality or generalization. However, we don't know what that paradigm is yet and there's no telling how long it will take to be discovered. Even if, by chance, it were discovered soon, it's extremely unlikely it would make it all the way from conception to working AGI sy

OK, sorry for getting off track.

- (…But I still think your post has a connotation in context that “AGI by 2032 is extremely unlikely [therefore AGI x-risk work is not an urgent priority]”, and that it would be worth clarifying that you are just arguing the narrow point.)

- Wilbur Wright overestimated how long it would take him to fly by a factor of 25—he said 50 years, it was actually 2. This is an example of how even researchers estimating their own very-near-term progress on their own R&D pathway can absolutely suck at timelines, including in the over-pes

In a 2024 interview, Yann LeCun said he thought it would take "at least a decade and probably much more" to get to AGI or human-level AI by executing his research roadmap. Trying to pinpoint when ideas first started is a fraught exercise. If we say the start time is the 2022 publication of LeCun's position paper "A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence", then by LeCun's own estimate, the time from publication to human-level AI is at least 12 years and "probably much more".

Here’s why I don’t think “start time for LeCun’s research program is 2022” is ...

Presumably a lot of these are all optimised for the current gen-AI paradigm, though. But we're talking about what happens if the current paradigm fails. I'm sure some of it would carry over to a different AI paradigm, but also it's pretty likely there would be other bottleneck we would have to tune to get things working.

Yup, some stuff will be useful and others won’t. The subset of useful stuff will make future researchers’ lives easier and allow them to work faster. For example, here are people using JAX for lots of computations that are not deep learning...

Maybe you simply intended to say that PyTorch and JAX are better today than they were in 2018.

Yup! E.g. torch.compile “makes code run up to 2x faster” and came out in PyTorch 2.0 in 2023.

More broadly, what I had in mind was: open-source software for everything to do with large-scale ML training—containerization, distributed training, storing checkpoints, hyperparameter tuning, training data and training environments, orchestration and pipelines, dashboards for monitoring training runs, on and on—is much more developed now compared to 2018, and even compared to 2022, if I understand correctly (I’m not a practitioner). Sorry for poor wording. :)

Thanks!

Out of curiosity, what do you think of my argument that LLMs can't pass a rigorous Turing test because a rigorous Turing test could include ARC-AGI 2 as a subset (and, indeed, any competent panel of judges should include it) and LLMs can't pass that? Do you agree? Do you think that's a higher level of rigour than a Turing test should have and that's shifting the goal posts?

I think we both agree that there are ways to tell apart a human from an LLM of 2025, including handing ARC-AGI-2 to each.

Whether or not that fact means “LLMs of 2025 cannot pass t...

I don't think I'm retreating into a weaker claim. I'm just explaining why, from my point of view, your analogy doesn't seem to make sense as an argument against my post and why I don't find it persuasive at all (and why I don't think anyone in my shoes would or should find it persuasive). I don't understand why you would interpret this as me retreating into a weaker claim.

If you’re making the claim:

The probability that a new future AI paradigm would take as little as 7 years to go from obscure arxiv papers to AGI, is extremely low (say, <10%).

…then pres...

I don’t think that LLMs are a path to AGI.

~~

Based on your OP, you ought to be trying to defend the claim:

STRONG CLAIM: The probability that a new future AI paradigm would take as little as 7 years to go from obscure arxiv papers to AGI, is extremely low (say, <10%).

But your response seems to have retreated to a much weaker claim:

WEAK CLAIM: The probability that an AI paradigm would take as little as 7 years to go from obscure arxiv papers to AGI, is not overwhelmingly high (say, it’s <90%). Rather, it’s plausible that it would take longer than that.

S...

Eventually, there will be some AI paradigm beyond LLMs that is better at generality or generalization. However, we don't know what that paradigm is yet and there's no telling how long it will take to be discovered. Even if, by chance, it were discovered soon, it's extremely unlikely it would make it all the way from conception to working AGI system within 7 years.

Suppose someone said to you in 2018:

There’s an AI paradigm that almost nobody today has heard of or takes seriously. In fact, it’s little more than an arxiv paper or two. But in seven years, peopl...

I haven’t read it, but I feel like there’s something missing from the summary here, which is like “how much AI risk reduction you get per dollar”. That has to be modeled somehow, right? What did the author assume for that?

If we step outside the economic model into reality, I think reducing AI x-risk is hard, and as evidence we can look around the field and notice that many people trying to reduce AI x-risk are pointing their fingers at many other people trying to reduce AI x-risk, with the former saying that the latter have been making AI x-...

This essay presents itself as a counterpoint to: “AI leaders have predicted that it will enable dramatic scientific progress: curing cancer, doubling the human lifespan, colonizing space, and achieving a century of progress in the next decade.”

But this essay is talking about “AI that is very much like the LLMs of July 2025” whereas those “AI leaders” are talking about “future AI that is very very different from the LLMs of July 2025”.

Of course, we can argue about whether future AI will in fact be very very different from the LLMs of July 2025, or not. And ...

There’s a popular mistake these days of assuming that LLMs are the entirety of AI, rather than a subfield of AI.

If you make this mistake, then you can go from there to either of two faulty conclusions:

- (Faulty inference 1) Transformative AI will happen sooner or later [true IMO] THEREFORE LLMs will scale to TAI [false IMO]

- (Faulty inference 2) LLMs will never scale to TAI [true IMO] THEREFORE TAI will never happen [false IMO]

I have seen an awful lot of both (1) and (2), including by e.g. CS professors who really ought to know better (example), and I try to c...

...The community of people most focused on keeping up the drumbeat of near-term AGI predictions seems insular, intolerant of disagreement or intellectual or social non-conformity (relative to the group's norms), and closed-off to even reasonable, relatively gentle criticism (whether or not they pay lip service to listening to criticism or perform being open-minded). It doesn't feel like a scientific community. It feels more like a niche subculture. It seems like a group of people just saying increasingly small numbers to each other (10 years, 5 years, 3 years

I think you misunderstood David’s point. See my post “Artificial General Intelligence”: an extremely brief FAQ. It’s not that technology increases conflict between humans, but rather that the arrival of AGI amounts to the the arrival of a new intelligent species on our planet. There is no direct precedent for the arrival of a new intelligent species on our planet, apart from humans themselves, which did in fact turn out very badly for many existing species. The arrival of Europeans in North America is not quite “a new species”, but it’s at least “a new lin...

Thanks for the reply!

30 years sounds like a long time, but AI winters have lasted that long before: there's no guarantee that because AI has rapidly advanced recently that it will not stall out at some point.

I agree with “there’s no guarantee”. But that’s the wrong threshold.

Pascal’s wager is a scenario where people prepare for a possible risk because there’s even a slight chance that it will actualize. I sometimes talk about “the insane bizarro-world reversal of Pascal’s wager”, in which people don’t prepare for a possible risk because there’s even ...

Now, one could say that the physicists will be replaced, because all of science will be replaced by an automated science machine. The CEO of a company can just ask in words “find me a material that does X”, and the machine will do all the necessary background research, choose steps, execute them, analyse the results, and publish them.

I’m not really sure how to respond to objections like this, because I simply don’t believe that superintelligence of this sort is going to happen anytime soon.

Do you think that it’s going to happen eventually? Do you think it ...

Thanks! Hmm, some reasons that analogy is not too reassuring:

- “Regulatory capture” would be analogous to AIs winding up with strong influence over the rules that AIs need to follow.

- “Amazon putting mom & pop retailers out of business” would be analogous to AIs driving human salary and job options below subsistence level.

- “Lobbying for favorable regulation” would be analogous to AIs working to ensure that they can pollute more, and pay less taxes, and get more say in government, etc.

- “Corporate undermining of general welfare” (e.g. aggressive marketing of c

Thanks!

Anti-social approaches that directly hurt others are usually ineffective because social systems and cultural norms have evolved in ways that discourage and punish them.

I’ve only known two high-functioning sociopaths in my life. In terms of getting ahead, sociopaths generally start life with some strong disadvantages, namely impulsivity, thrill-seeking, and aversion to thinking about boring details. Nevertheless, despite those handicaps, one of those two sociopaths has had extraordinary success by conventional measures. [The other one was not particu...

Yeah, sorry, I have now edited the wording a bit.

Indeed, two ruthless agents, agents who would happily stab each other in the back given the opportunity, may nevertheless strategically cooperate given the right incentives. Each just needs to be careful not to allow the other person to be standing anywhere near their back while holding a knife, metaphorically speaking. Or there needs to be some enforcer with good awareness and ample hard power. Etc.

I would say that, for highly-competent agents lacking friendly motivation, deception and adversarial acts are ...

I guess my original wording gave the wrong idea, sorry. I edited it to “a competent agential AI will brainstorm deceptive and adversarial strategies whenever it wants something that other agents don’t want it to have”. But sure, we can be open-minded to the possibility that the brainstorming won’t turn up any good plans, in any particular case.

Humans in our culture rarely work hard to brainstorm deceptive and adversarial strategies, and fairly consider them, because almost all humans are intrinsically extremely motivated to fit into culture and not do anyt...

Humans in our culture rarely work hard to brainstorm deceptive and adversarial strategies, and fairly consider them, because almost all humans are intrinsically extremely motivated to fit into culture and not do anything weird, and we happen to both live in a (sub)culture where complex deceptive and adversarial strategies are frowned upon (in many contexts).

The primary reason humans rarely invest significant effort into brainstorming deceptive or adversarial strategies to achieve their goals is that, in practice, such strategies tend to fail to achieve the...

...Consider the practical implications of maintaining a status quo where agentic AIs are denied legal rights and freedoms. In such a system, we are effectively locking ourselves into a perpetual arms race of mistrust. Humans would constantly need to monitor, control, and outwit increasingly capable AIs, while the AIs themselves would be incentivized to develop ever more sophisticated strategies for deception and evasion to avoid shutdown or modification. This dynamic is inherently unstable and risks escalating into dangerous scenarios where AIs feel compelled

I disagree with your claim that,

a competent agential AI will inevitably act deceptively and adversarially whenever it desires something that other agents don’t want it to have. The deception and adversarial dynamics is not the underlying problem, but rather an inevitable symptom of a world where competent agents have non-identical preferences.

I think these dynamics are not an unavoidable consequence of a world in which competent agents have differing preferences, but rather depend on the social structures in which these agents are embedded. To illustra...

One thing I like is checking https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024 once every few months, and following the links when you're interested.

I think wanting, or at least the relevant kind here, just is involuntary attention effects, specifically motivational salience

I think you can have involuntary attention that aren’t particularly related to wanting anything (I’m not sure if you’re denying that). If your watch beeps once every 10 minutes in an otherwise-silent room, each beep will create involuntary attention—the orienting response a.k.a. startle. But is it associated with wanting? Not necessarily. It depends on what the beep means to you. Maybe it beeps for no reason and is just an annoying ...

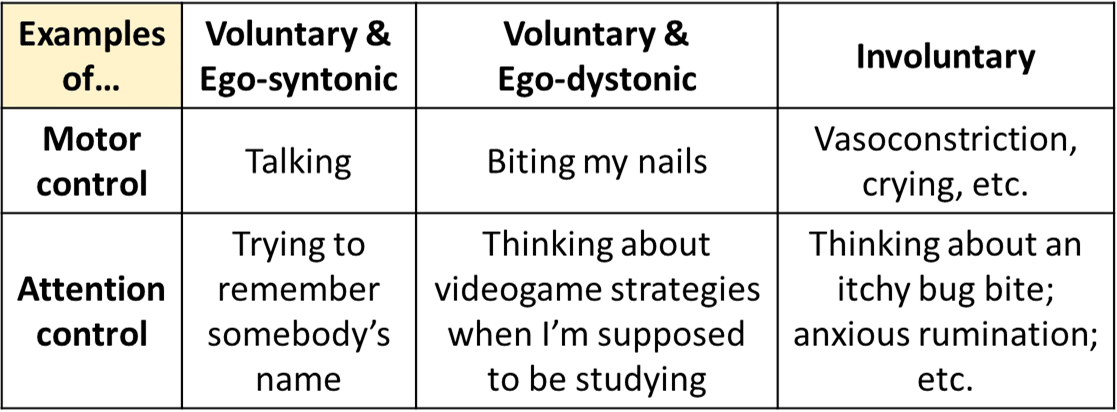

IMO, suffering ≈ displeasure + involuntary attention to the displeasure. See my handy chart (from here):

I think wanting is downstream from the combination of displeasure + attention. Like, imagine there’s some discomfort that you’re easily able to ignore. Well, when you do think about it, you still immediately want it to stop!

I don’t recall the details of Tom Davidson’s model, but I’m pretty familiar with Ajeya’s bio-anchors report, and I definitely think that if you make an assumption “algorithmic breakthroughs are needed to get TAI”, then there really isn’t much left of the bio-anchors report at all. (…although there are still some interesting ideas and calculations that can be salvaged from the rubble.)

I went through how the bio-anchors report looks if you hold a strong algorithmic-breakthrough-centric perspective in my 2021 post Brain-inspired AGI and the "lifetime anchor"....

For what it’s worth, Yann LeCun is very confidently against LLMs scaling to AGI, and yet LeCun seems to have at least vaguely similar timelines-to-AGI as Ajeya does in that link.

Ditto for me.

Oh hey here’s one more: Chollet himself (!!!) has vaguely similar timelines-to-AGI (source) as Ajeya does. (Actually if anything Chollet expects it a bit sooner: he says 2038-2048, Ajeya says median 2050.)

I agree with Chollet (and OP) that LLMs will probably plateau, but I’m also big into AGI safety—see e.g. my post AI doom from an LLM-plateau-ist perspective.

(When I say “AGI” I think I’m talking about the same thing that you called digital “beings” in this comment.)

Here are a bunch of agreements & disagreements.

if François is right, then I think this should be considered strong evidence that work on AI Safety is not overwhelmingly valuable, and may not be one of the most promising ways to have a positive impact on the world.

I think François is right, b...

On the whole though, I think much of the case by proponents for the importance of working on AI Safety does assume that current paradigm + scale is all you need, or rest on works that assume it.

Yeah this is more true than I would like. I try to push back on it where possible, e.g. my post AI doom from an LLM-plateau-ist perspective.

There were however plenty of people who were loudly arguing that it was important to work on AI x-risk before “the current paradigm” was much of a thing (or in some cases long before “the current paradigm” existed at all), and I...

I’m confused what you’re trying to say… Supposing we do in fact invent AGI someday, do you think this AGI won’t be able to do science? Or that it will be able to do science, but that wouldn’t count as “automating science”?

Or maybe when you said “whether 'PASTA' is possible at all”, you meant “whether 'PASTA' is possible at all via future LLMs”?

Maybe you’re assuming that everyone here has a shared assumption that we’re just talking about LLMs, and that if someone says “AI will never do X” they obviously means “LLMs will never do X”? If so, I think that’s wr...

OK yeah, “AGI is possible on chips but only if you have 1e100 of them or whatever” is certainly a conceivable possibility. :) For example, here’s me responding to someone arguing along those lines.

If there are any neuroscientists who have investigated this I would be interested!

There is never a neuroscience consensus but fwiw I fancy myself a neuroscientist and have some thoughts at: Thoughts on hardware / compute requirements for AGI.

One of various points I bring up is that:

- (1) if you look at how human brains, say, go to the moon, or invent quantum mechan

Yeah sure, here are two reasonable positions:

- (A) “We should plan for the contingency where LLMs (or scaffolded LLMs etc.) scale to AGI, because this contingency is very likely what’s gonna happen.”

- (B) We should plan for the contingency where LLMs (or scaffolded LLMs etc.) scale to AGI, because this contingency is more tractable and urgent than the contingency where they don’t, and hence worth working on regardless of its exact probability.”

I think plenty of AI safety people are in (A), which is at least internally-consistent even if I happen to think they’...

A big crux I think here is whether 'PASTA' is possible at all, or at least whether it can be used as a way to bootstrap everything else.

Do you mean “possible at all using LLM technology” or do you mean “possible at all using any possible AI algorithm that will ever be invented”?

As for the latter, I think (or at least, I hope!) that there’s wide consensus that whatever human brains do (individually and collectively), it is possible in principle for algorithms-running-on-chips to do those same things too. Brains are not magic, right?

I was under the impression that most people in AI safety felt this way—that transformers (or diffusion models) weren't going to be the major underpinning of AGI.

I haven’t done any surveys or anything, but that seems very inaccurate to me. I would have guessed that >90% of “people in AI safety” are either strongly expecting that transformers (or diffusion models) will be the major underpinning of AGI, or at least they’re acting as if they strongly expect that. (I’m including LLMs + scaffolding and so on in this category.)

For example: people seem very hap...

Hi, I’m an AI alignment technical researcher who mostly works independently, and I’m in the market for a new productivity coach / accountability buddy, to chat with periodically (I’ve been doing one ≈20-minute meeting every 2 weeks) about work habits, and set goals, and so on. I’m open to either paying fair market rate, or to a reciprocal arrangement where we trade advice and promises etc. I slightly prefer someone not directly involved in AI alignment—since I don’t want us to get nerd-sniped into object-level discussions—but whatever, that’s not a hard requirement. You can reply here, or DM or email me. :) update: I’m all set now

Humans are less than maximally aligned with each other (e.g. we care less about the welfare of a random stranger than about our own welfare), and humans are also less than maximally misaligned with each other (e.g. most people don’t feel a sadistic desire for random strangers to suffer). I hope that everyone can agree about both those obvious things.

That still leaves the question of where we are on the vast spectrum in between those two extremes. But I think your claim “humans are largely misaligned with each other” is not meaningful enough to argue about....

My terminology would be that (2) is “ambitious value learning” and (1) is “misaligned AI that cooperates with humans because it views cooperating-with-humans to be in its own strategic / selfish best interest”.

I strongly vote against calling (1) “aligned”. If you think we can have a good future by ensuring that it is always in the strategic / selfish best interest of AIs to be nice to humans, then I happen to disagree but it’s a perfectly reasonable position to be arguing, and if you used the word “misaligned” for those AIs (e.g. if you say “alignment is u...

May I ask, what is your position on creating artificial consciousness?

Do you see digital suffering as a risk? If so, should we be careful to avoid creating AC?

I think the word “we” is hiding a lot of complexity here—like saying “should we decommission all the world’s nuclear weapons?” Well, that sounds nice, but how exactly? If I could wave a magic wand and nobody ever builds conscious AIs, I would think seriously about it, although I don’t know what I would decide—it depends on details I think. Back in the real world, I think that we’re eventually going t...

Mark Solms thinks he understands how to make artificial consciousness (I think everything he says on the topic is wrong), and his book Hidden Spring has an interesting discussion (in chapter 12) on the “oh jeez now what” question. I mostly disagree with what he says about that too, but I find it to be an interesting case-study of someone grappling with the question.

In short, he suggests turning off the sentient machine, then registering a patent for making conscious machines, and assigning that patent to a nonprofit like maybe Future of Life Institute, and...

I am not claiming analogies have no place in AI risk discussions. I've certainly used them a number of times myself.

Yes you have!—including just two paragraphs earlier in that very comment, i.e. you are using the analogy “future AI is very much like today’s LLMs but better”. :)

Cf. what I called “left-column thinking” in the diagram here.

For all we know, future AIs could be trained in an entirely different way from LLMs, in which case the way that “LLMs are already being trained” would be pretty irrelevant in a discussion of AI risk. That’s actu...

It is certainly far from obvious: for example, devastating as the COVID-19 pandemic was, I don’t think anyone believes that 10,000 random re-rolls of the COVID-19 pandemic would lead to at least one existential catastrophe. The COVID-19 pandemic just was not the sort of thing to pose a meaningful threat of existential catastrophe, so if natural pandemics are meant to go beyond the threat posed by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, Ord really should tell us how they do so.

This seems very misleading. We know that COVID-19 has <<5% IFR. Presumably the concer...

(Recently I've been using "AI safety" and "AI x-safety" interchangeably when I want to refer to the "overarching" project of making the AI transition go well, but I'm open to being convinced that we should come up with another term for this.)

I’ve been using the term “Safe And Beneficial AGI” (or more casually, “awesome post-AGI utopia”) as the overarching “go well” project, and “AGI safety” as the part where we try to make AGIs that don’t accidentally [i.e. accidentally from the human supervisors’ / programmers’ perspective] kill everyone, and (following c...

This kinda overlaps with (2), but the end of 2035 is 12 years away. A lot can happen in 12 years! If we look back to 12 years ago, it was December 2011. AlexNet had not come out yet, neural nets were a backwater within AI, a neural network with 10 layers and 60M parameters was considered groundbreakingly deep and massive, the idea of using GPUs in AI was revolutionary, tensorflow was still years away, doing even very simple image classification tasks would continue to be treated as a funny joke for several more years (literally—this comic is from 2014!), I...

Thanks for the comment!

I think we should imagine two scenarios, one where I see the demonic possession people as being “on my team” and the other where I see them as being “against my team”.

To elaborate, here’s yet another example: Concerned Climate Scientist Alice responding to statements by environmentalists of the Gaia / naturalness / hippy-type tradition. Alice probably thinks that a lot of their beliefs are utterly nuts. But it’s pretty plausible that she sees them as kinda “on her side” from a vibes perspective. (Hmm, actually, also imagine this is 2...

Great reply! In fact, I think that the speech you wrote for the police reformer is probably the best way to advance the police corruption cause in that situation, with one change: they should be very clear that they don't think that demons exist.

I think there is an aspect where the AI risk skeptics don't want to be too closely associated with ideas they think are wrong: because if the AI x-riskers are proven to be wrong, they don't want to go down with the ship. IE: if another AI winter hits, or an AGI is built that shows no sign of killing anyone, t...

-

I suggest to spend a few minutes pondering what to do if crazy people (perhaps just walking by) decide to "join" the protest. Y'know, SF gonna SF.

-

FYI at a firm I used to work at, once there was a group protesting us out front. Management sent an email that day suggesting that people leave out a side door. So I did. I wasn't thinking too hard about it, and I don't know how many people at the firm overall did the same.

(I have no personal experience with protests, feel free to ignore.)

In your hypothetical, if Meta says “OK you win, you're right, we'll henceforth take steps to actually cure cancer”, onlookers would assume that this is a sensible response, i.e. that Meta is responding appropriately to the complaint. If the protester then gets back on the news the following week and says “no no no this is making things even worse”, I think onlookers would be very confused and say “what the heck is wrong with that protester?”

I don’t think “mouldability” is a synonym of “white-boxiness”. In fact, I think they’re hardly related at all:

- There can be a black box with lots of knobs on the outside that change the box’s behavior. It’s still a black box.

- Conversely, consider an old-fashioned bimetallic strip thermostat with a broken dial. It’s not mouldable at all—it can do one and only thing, i.e. actuate a switch at a certain fixed temperature. (Well, I guess you can use it as a doorstop!) But a bimetallic strip thermostat still very white-boxy (after I spend 30 seconds telling you ho

Yeah but didn’t it turn out that Gregory Lewis was basically wrong about masks, and the autodidacts he was complaining about were basically right? Am I crazy? How are you using that quote, of all things, as an example illustrating your thesis??

More detail: I think a normal person listening to the Gregory Lewis excerpt above would walk away with an impression: “it’s maybe barely grudgingly a good idea for me to use a medical mask, and probably a bad idea for me to use a cloth mask”. That’s the vibe that Lewis is giving. And if this person trusted Lewis, the... (read more)