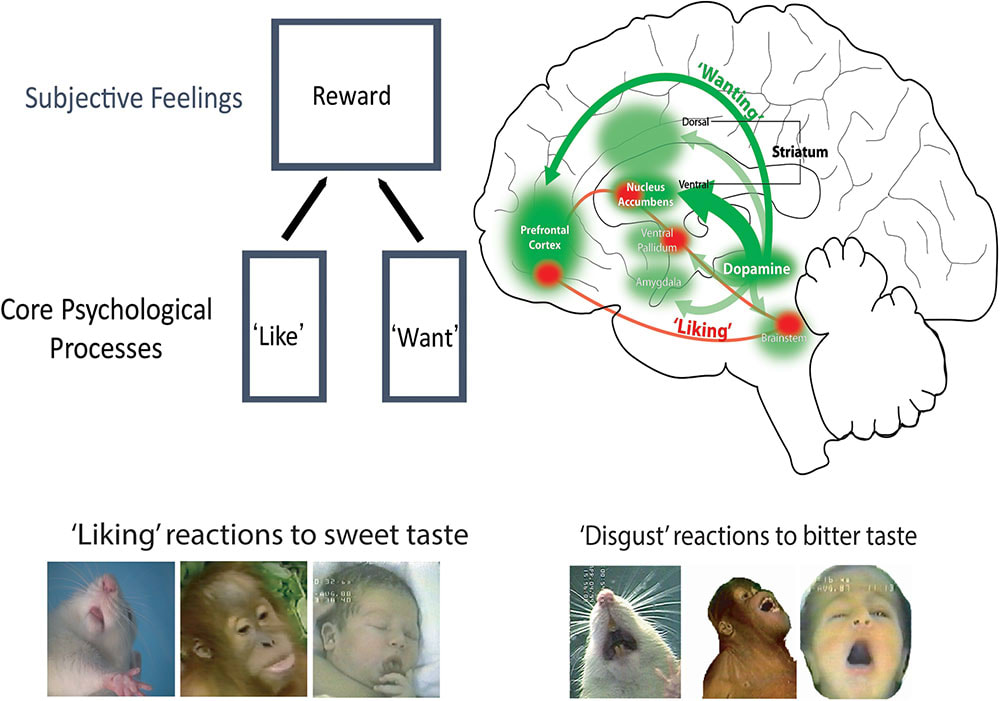

Pleasure and suffering are not conceptual opposites. Rather, pleasure and unpleasantness are conceptual opposites. Pleasure and unpleasantness are liking and disliking, or positive affect and negative affect, respectively.[1]

Imagine an experience of suffering that involved little or no effects on your attention. It's easy to ignore, along with whatever is causing it and whatever could help relieve it. We (or at least, I) would either recognize this as at most mild suffering, and perhaps not suffering at all.

Our concept of suffering probably includes both unpleasantness and desire (or wanting), which is mediated by motivational salience (or incentive salience and aversive/threat/fearful salience), a mechanism for pulling our attention (Berridge, 2018).[2] I'd guess the apparent moral urgency we assign to intense suffering requires intense desire, and so strong effects on attention. We wouldn't mind an intensely unpleasant experience if it had no effects on our attention,[3] although it's hard for me to imagine what that would even be like. I find it easier to imagine intense pleasure without strong effects on attention.

Pleasure and unpleasantness need not involve desire, at least conceptually, and it seems pleasure at least does not require desire in humans. Desire, as motivational salience, depends on brain mechanisms in animals distinct from those for pleasure, and which can be separately manipulated (Berridge, 2018, Nguyen et al., 2021, Berridge & Dayan, 2021), including by reducing desire (incentive salience) without also reducing drug-induced euphoria (Leyton et al., 2007, Brauer & H De Wit, 1997). Berridge and Kringelbach (2015) summarize the last two studies as follows:

human subjective ratings of drug pleasure (e.g., cocaine) are not reduced by pharmacological disruption of dopamine systems, even when dopamine suppression does reduce wanting ratings (Brauer and De Wit, 1997, Leyton et al., 2007)

On the other hand, in humans and other animals, the aversive salience of physical pain may not be empirically separable from its unpleasantness (Shriver, 2014), but as far as I can tell, the issue is not settled.

- ^

Or specifically the conscious versions of these. On the possibility of unconscious liking and unconscious emotion, see Berridge & Winkielman, 2003 (pdf) and Winkielman & Berridge, 2004.

- ^

And perhaps specifically aversive desire, i.e. aversive/threat salience.

- ^

This could be true by definition, if "to mind" is taken to mean "to pay attention to" or find aversive (aversive salience), at least while experiencing the unpleasantness.

I think you can have involuntary attention that aren’t particularly related to wanting anything (I’m not sure if you’re denying that). If your watch beeps once every 10 minutes in an otherwise-silent room, each beep will create involuntary attention—the orienting response a.k.a. startle. But is it associated with wanting? Not necessarily. It depends on what the beep means to you. Maybe it beeps for no reason and is just an annoying distraction from something you’re trying to focus on. Or maybe it’s a reminder to do something you like doing, or something you dislike doing, or maybe it just signifies that you’re continuing to make progress and it has no action-item associated with it. Who knows.

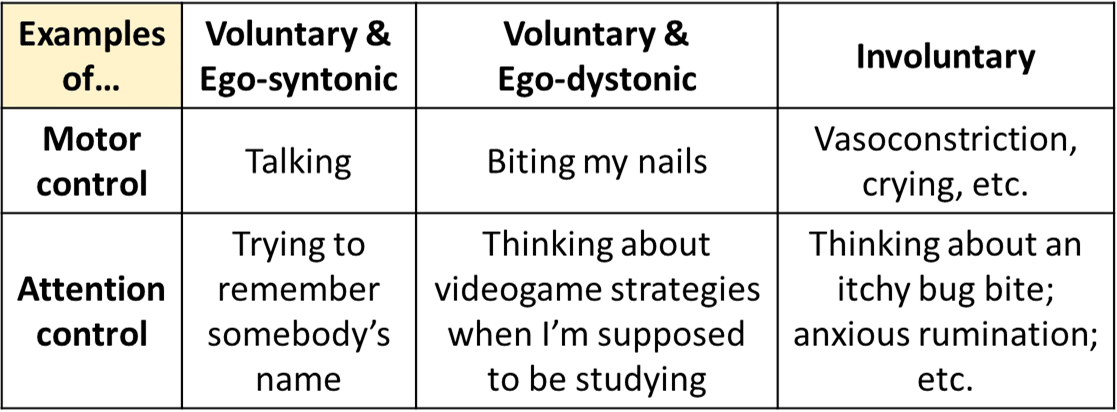

In my ontology, voluntary actions (both attention actions and motor actions) happen if and only if the idea of doing them is positive-valence, while involuntary actions (again both attention actions and motor actions) can happen regardless of their valence. In other words, if the reinforcement learning system is the reason that something is happening, it’s “voluntary”.

Orienting responses are involuntary (with both involuntary motor aspects and involuntary attention aspects). It doesn’t matter if orienting to a sudden loud sound has led to good things happening in the past, or bad things in the past. You’ll orient to a sudden loud sound either way. By the same token, paying attention to a headache is involuntary. You’re not doing it because doing similar things has worked out well for you in the past. Quite the contrary, paying attention to the headache is negative valence. If it was just reinforcement learning, you simply wouldn’t think about the headache ever, to a first approximation. Anyway, over the course of life experience, you learn habits / strategies that apply (voluntary) attention actions and motor actions towards not thinking about the headache. But those strategies may not work, because meanwhile the brainstem is sending involuntary attention signals that overrule them.

So for example, “ugh fields” are a strategy implemented via voluntary attention to preempt the possibility of triggering the unpleasant involuntary-attention process of anxious rumination.

The thing you wrote is kinda confusing in my ontology. I’m concerned that you’re slipping into a mode where there’s a soul / homunculus “me” that gets manipulated by the exogenous pressures of reinforcement learning. If so, I think that’s a bad ontology—reinforcement learning is not an exogenous pressure on the “me” concept, it is part of how the “me” thing works and why it wants what it wants. Sorry if I’m misunderstanding.