Pleasure and suffering are not conceptual opposites. Rather, pleasure and unpleasantness are conceptual opposites. Pleasure and unpleasantness are liking and disliking, or positive affect and negative affect, respectively.[1]

Imagine an experience of suffering that involved little or no effects on your attention. It's easy to ignore, along with whatever is causing it and whatever could help relieve it. We (or at least, I) would either recognize this as at most mild suffering, and perhaps not suffering at all.

Our concept of suffering probably includes both unpleasantness and desire (or wanting), which is mediated by motivational salience (or incentive salience and aversive/threat/fearful salience), a mechanism for pulling our attention (Berridge, 2018).[2] I'd guess the apparent moral urgency we assign to intense suffering requires intense desire, and so strong effects on attention. We wouldn't mind an intensely unpleasant experience if it had no effects on our attention,[3] although it's hard for me to imagine what that would even be like. I find it easier to imagine intense pleasure without strong effects on attention.

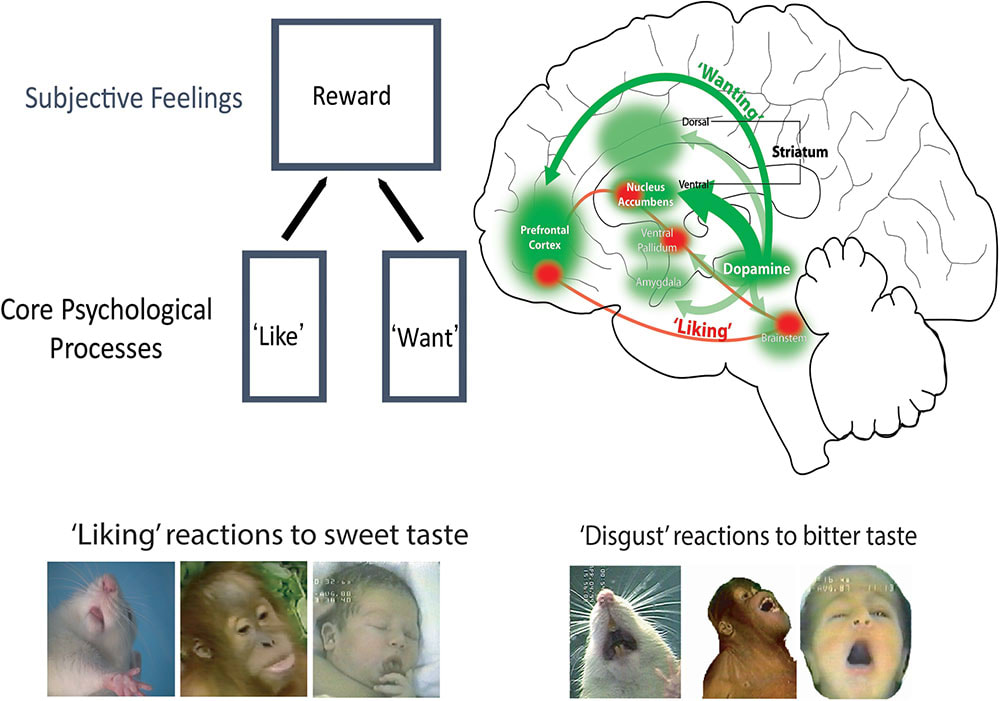

Pleasure and unpleasantness need not involve desire, at least conceptually, and it seems pleasure at least does not require desire in humans. Desire, as motivational salience, depends on brain mechanisms in animals distinct from those for pleasure, and which can be separately manipulated (Berridge, 2018, Nguyen et al., 2021, Berridge & Dayan, 2021), including by reducing desire (incentive salience) without also reducing drug-induced euphoria (Leyton et al., 2007, Brauer & H De Wit, 1997). Berridge and Kringelbach (2015) summarize the last two studies as follows:

human subjective ratings of drug pleasure (e.g., cocaine) are not reduced by pharmacological disruption of dopamine systems, even when dopamine suppression does reduce wanting ratings (Brauer and De Wit, 1997, Leyton et al., 2007)

On the other hand, in humans and other animals, the aversive salience of physical pain may not be empirically separable from its unpleasantness (Shriver, 2014), but as far as I can tell, the issue is not settled.

- ^

Or specifically the conscious versions of these. On the possibility of unconscious liking and unconscious emotion, see Berridge & Winkielman, 2003 (pdf) and Winkielman & Berridge, 2004.

- ^

And perhaps specifically aversive desire, i.e. aversive/threat salience.

- ^

This could be true by definition, if "to mind" is taken to mean "to pay attention to" or find aversive (aversive salience), at least while experiencing the unpleasantness.

Unpleasantness doesn't only apply to sensations. I think sadness, like as an empathetic response to the bug struggling, involves unpleasantness/negative affect. That's the case on most models, AFAIK. I agree (or suspect) it's not the sensations (visual experience) that are unpleasant.

To add to this, there’s evidence negative valence depends on brain regions common to unpleasant physical pain, empathic pains and social pains (from social rejection, exclusion, or loss) (Singer et al., 2004, Eisenberger, 2015). In particular, the title of Singer et al., 2004 is "Empathy for Pain Involves the Affective but not Sensory Components of Pain".

I'm not sure either way whether I'd generally consider sadness to be suffering, though. I'd say suffering is at least unpleasantness + desire (or maybe unpleasantness + aversive desire specifically), but I'm not sure that's all it is. I might also be inclined to use some desire (and unpleasantness) intensity cutoff to call something suffering, but that might be too arbitrary.

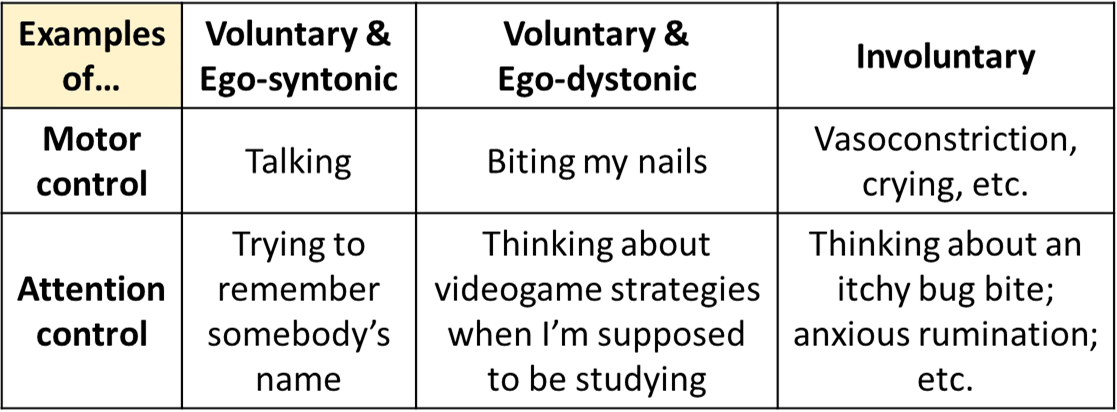

You're right that I didn't define desire. The kind of desire I had in mind in this post basically just is motivational (incentive + aversive) salience, which is a neurological mechanism that affects (biases) your attention.[1] There might be more to this kind of desire, but I think motivational salience is a lot of it, and could be all of it. (There are other types of desires, like goals, but those are not what I have in mind here.)

Brody (2018, 2023) defines suffering so that an individual suffers when “she has an unpleasant or negative affective experience that she minds, where to mind some state is to have an occurrent desire that the experience not be occurring.” Unpleasantness and aversion wouldn't be enough for suffering: there must be aversion to the experience itself. Whereas, instead, we could be averse to other things outside of us, like a bear we're afraid of, rather than to the experience itself.

I have some sympathy for this definition, but I'm also not sure it even makes sense. If this kind of "occurrent desire" is just aversive salience, how exactly would it apply differently from when we're afraid of a bear, say? If it's not aversive salience, then what kind of desire is it and how exactly does that work?

It's a different mechanism from the one for (bottom-up) stimulus intensity, and the one for (top-down) task-based attention control. From Kim et al., 2021: