Introduction

When I first read about effective altruism, it wasn’t long until I came across the importance-neglectedness-tractability (INT) framework. Almost immediately upon reading a description of the framework I stopped and excitedly said aloud “wait, this is just the stock issues! … Sort of…!”

For years, I had practically been preaching the stock issues framework—the poorly named, varyingly conceived, and occasionally misapplied decision-evaluation framework which nonetheless rests at the heart of competitive policy debate in many high school leagues. It just seemed like such a simple and effective way to improve decision making, yet I had never seen even a generic/alternatively-named version of it outside of debaterland. Then, lo and behold, I find the 80,000 Hours description of the INT framework. (The framework turned out to be just one of many EA-related concepts that I had loosely articulated/supported even prior to actually learning about EA)

Yet, I soon came to see that they are distinct in some key ways, even if they are conceptually similar. Furthermore, I saw that the stock issues framework seems to avoid some of the problems that people have pointed out with the INT framework (e.g., assumptions regarding diminishing marginal returns).

I will explain what the stock issues are in the next section, but I wanted to note up front that I still have not come across even a generic/alternatively-named version of the stock issues framework, even as I’ve looked through EA forum/concepts posts where I thought I might find some mention of a decision-centered framework[ftn 1] like the stock issues, only to instead find references to things like typical cost-benefit analysis or the INT framework. I had considered but delayed writing a comment/post on this for some time, but then I saw this post and didn’t see any mention of this concept,[2] so I felt compelled to finally write this post.

Brief Outline

In this post, I hope to:

- Introduce and explain a framework for evaluating decisions which at least seems (based on some mild-moderate research) to be surprisingly unarticulated/unknown in the EA community;

- Partially compare/contrast it with the INT framework;

- Solicit some feedback/thoughts on the framework, especially regarding its applicability to EA, and also ask some more general questions (e.g., “have you seen this framework or something similar”)

I will say up front that I may be imprecise at times in my definitions (among other things), since it’s a lot to cover and I don’t want to write something so long [3] and nuanced in an introduction article (for both your sake and mine); if needed, I can clarify things in response to questions.

What is the stock issues framework?

Because people are often initially confused, I’ll first note that it has nothing to do with “stocks” as in the stock market; the “stock” part of the name just refers to “key/central” issues. Second, even though in my experience most debaters refer to “it” as “a” universal concept (i.e., “the” stock issues), there are lots of minor variations in how people conceive of the framework (e.g., how they define the issues and which issues they include). My interpretation, though, is notably unique—in large part since I’ve tried to adapt the framework for use outside of just competitive policy debate rounds. Additionally, as is the case with the INT framework, there are “informal” (heuristic) and “formal” (more-rigorously defined) conceptions of the framework. However, for now I will typically focus on defining it in the more-formal sense, especially since the two aren’t radically different. [4]

With those points out of the way, I can finally outline the framework, then respond to commentary/objections as needed. (If you want a longer explanation, you can read these two articles.)

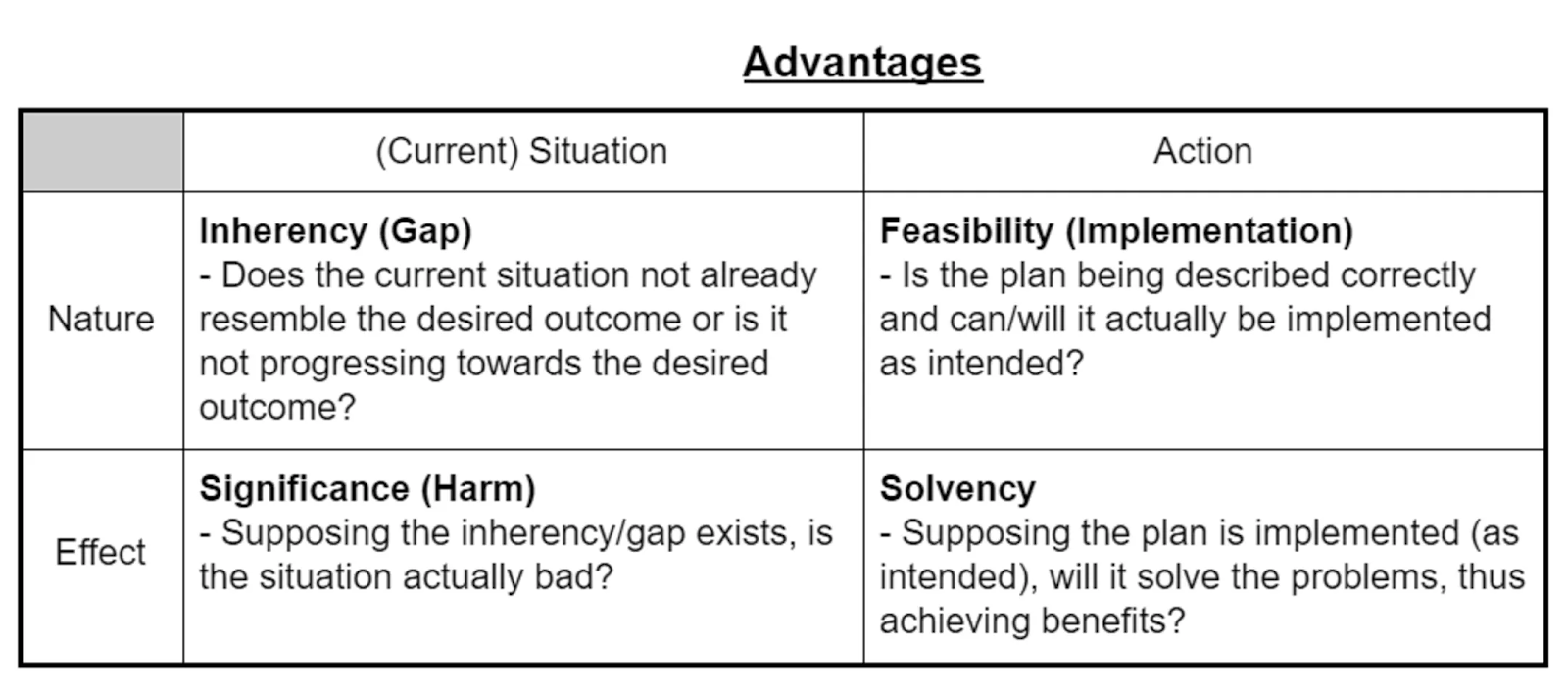

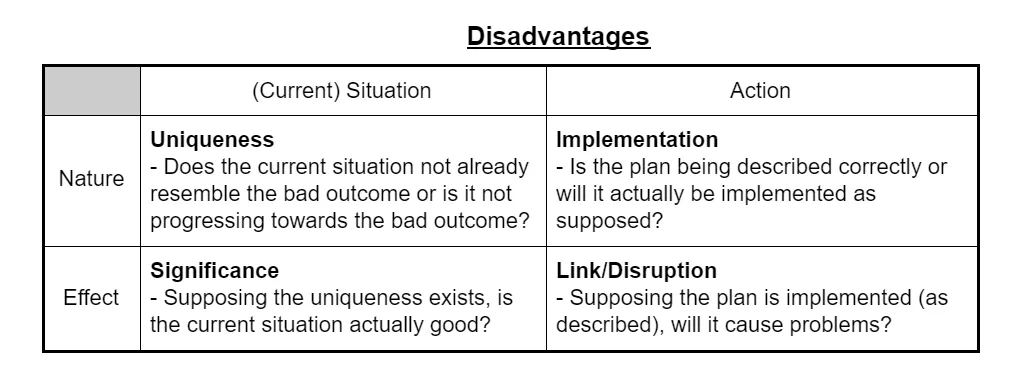

In short, the framework breaks down the analysis of individual costs and benefits (i.e., each advantage and disadvantage) of a decision into four smaller, more-manageable claims/concepts which are linked and collectively exhaustive—and, in the formal conception, conceptually distinct. Thus, it is used to scrutinize or measure the expected/claimed advantages and disadvantages of a decision.

As illustrated by the diagrams later on, these four issues roughly map onto a 2x2 matrix along lines similar to “before/after” and “cause/effect” (but not exactly those terms, as clarified in the diagrams). Before I explain each one individually, I think it helps to briefly outline what they generically look like together when explaining benefits/advantages:

- Inherency/Gap: There is a particular aspect of the status quo (or its future)... (somewhat similar to INT’s neglectedness mixed with parts of importance)

- Significance: Which is bad/nonoptimal… (somewhat similar to “importance”)

- Feasibility/Implementation: But a course of action could/would be taken… (related to tractability)

- Solvency [5]: Which would fix/improve that aspect of the status quo. (related to tractability)

(For anyone who actually is familiar with traditional stock issue theory in policy debate and is wondering where topicality is, the short answer is that I don’t include it since it is a “pseudo/heuristic issue” which is just highly useful given the rules of policy debate but logically redundant—as I explain in more detail here.)

It’s rather unfortunate that the first stock issue is the worst-named and most confusing, but basically it just makes the purely descriptive claims regarding what the current situation is and/or what the future will be like without the decision in question. It’s helpful to consider it in conjunction/contrast with significance, which is where one attaches a normative (“good/bad”) dimension to the inherency claims.[6] Together, these two points make up something similar to the “before” part of a loose “before/after” analysis.

The third stock issue, feasibility/implementation, essentially relates to the question “to what extent can/will the decision actually be implemented?” Again, it helps to consider this in conjunction/contrast with the next issue, solvency. Solvency basically refers to the claims regarding the effects of the decision/plan, supposing it is implemented in a certain way or to a certain extent.

The four points interact to create something of a multiplication equation (somewhat similar to the INT framework) which can be used when evaluating the individual costs and benefits in a cost-benefit analysis. Policy debaters generally simplify the framework and just say things like “an advantage’s weight is the degree to which an issue is inherent (e.g., the amount of pollution that exists) times the degree to which it is significant (e.g., the severity of that pollution existing) times the degree to which the plan solves it (e.g., how much pollution is reduced by the plan).” That’s somewhat imprecise/informal; it is probably better described at least as a product of functions if not a singular nest of functions. However, for now I’ll just leave it at that, and clarify/formalize later. One of the key reasons for highlighting its multiplicative nature, though, is the interdependence of the issues: if a decision seeks to fix a definitely-existent and normatively serious problem, but has either 0% feasibility or 0% solvency, it’s basically irrelevant.

At one point, I decided to try to illustrate these concepts visually by creating a diagram that essentially creates a loose 2x2 matrix (and has questions associated with each stock issue); I personally acknowledge these diagrams might be imprecise and a bit clunky (especially some of the row/column labels), but the diagrams are mainly just meant to illustrate the framework’s underlying reasoning (i.e., that it just slices up the analysis of an advantage into smaller parts—along lines reminiscent of “before/after” and “cause/effect”). Here is the diagram for advantages:

The same kind of analysis can be done for disadvantages, as illustrated by the following diagram. Note: although the names of the issues are different (due to policy debate jargon, tradition, etc.), the concepts being described are basically all the same except towards a negative end.

To apply it all in a relatively simple example, let’s suppose the decision in question is whether your organization should allocate $10,000 to a charity dealing with some health intervention. The stock issues framework holds that for any individual advantage that you claim stems from that decision, it logically must address the four criteria:

- Inherency: What is the extent/nature of the situation or issue in question, descriptively speaking? How many people actually have or are at risk of having the condition? Is there any money already allocated to deal with this issue? (Note, though, that this does not in itself determine “diminishing marginal returns.” To evaluate diminishing marginal returns requires combining this factual/descriptive understanding of the status quo with the analysis in solvency.)

- Significance: Does the current situation actually matter, normatively speaking? How much do the people in question suffer? Is this relevant under the/a valid moral framework (or “the moral framework we have justified and are operating under”)?

- Feasibility/implementation: Will this plan actually get implemented (as supposed)? Do we actually have $10,000 that we can allocate? Can we do it in the proposed timeframe? Will this require some funding or personnel which is not allocated?

- Solvency: Supposing we do implement the decision (or, for each possible degree of implementation), to what extent will this decision solve the problem described by inherency and significance?

Ultimately, like I said up front, it’s hard to strike a balance between preemptive clarifications/nuance and readability/writability (especially since I’m so familiar with it that I sometimes struggle to know where I might be losing people); given that I can address questions in comments and I’ve covered it with more examples elsewhere, I’ll mostly leave it at that for now.

Comparing/Contrasting With the INT Framework

I imagine that some of the comparisons to the INT framework might already be clear by this point, but I’ll note a few key points on their similarities and differences:

- Both frameworks try to break larger, more-complex questions into multiple smaller, more-manageable questions.

- The two frameworks both can have varying levels of formality in usage: the informal/less-restrictive approaches can serve as heuristics that spark questions (among other benefits); the formal approaches try to accurately identify the logic underpinning the analysis.

- The frameworks’ “issues” (individual points) have some loose similarities, such as neglectedness vs. inherency, tractability vs. solvency. However:

- Crucially, the stock issues and the INT framework have different “units of analysis”: the INT framework evaluates problem areas whereas the stock issues analyze decisions.

- Mainly as a result of this, the frameworks’ “issues” are meaningfully distinct. For example, the stock issues framework absorbs and splits some of the relevant aspects of neglectedness into inherency and solvency, while leaving out some of neglectedness’ problematic assumptions regarding diminishing marginal returns.

(A Future Update/Post: Why I Recommend/Use the Stock Issues Framework)

This is quite a can of worms to tackle, and this post has already gotten a bit long. In the past, I have made explicit arguments for why I think it is helpful in a variety of settings, and thus I can definitely try to give a defense of this. I think it would be more helpful/efficient, though, to get a sense of what people are or aren’t skeptical/confused about before trying to cast such a wide net of preemptive argumentation.

That being said, I will admit that I am less confident in the claim “The stock issues framework is very useful in a setting such as this (EA)” vs. claims like “The stock issues are collectively exhaustive” and “It is useful in analyzing policies,” but given my views on its effectiveness in other areas, I do expect it would likely at least be helpful to have as a tool in your back pocket, if nothing else.

Conclusion

Hopefully I have explained it decently enough—at least to the point that you can get the general idea and ask questions anywhere you are confused. Ultimately, through policy debate I have seen how it can be an effective framework for decision-making, so I figured that it could be helpful in certain aspects of EA decision-making, but have been surprised to see how little attention/awareness it seems to have in comparison with other frameworks.

I do recognize that the INT framework is meant to help guide thinking about general cause prioritization rather than individual decisions by evaluating problems’ characteristics (even if the goal is to help decisions such as “which cause should I prioritize”). However, when it comes to frameworks for decisions, I haven’t found much other than cost-benefit analysis as a formal/exhaustive foundation on one end with informal/non-exhaustive “pieces” or heuristics (e.g., urgency, hingeyness, the informal INT framework) on the other. In contrast, I would argue that the stock issues framework is just as exhaustive as basic cost-benefit analysis, yet also provides some “pieces” and heuristics that help guide/test your analysis. (As well as providing other benefits which I will discuss at a later time.)

Questions

- (A preliminary/implicit question: is my explanation clear, or are there parts I still need to clarify?)

- Is there anything in the EA community already like this—primarily, something which analyzes decisions (rather than problems) and breaks down the evaluative analysis in smaller but collectively exhaustive pieces?

- Has anyone seen anything else like this outside of EA or debate?

- I’d love to just get your general opinions on the framework, primarily in terms of “accuracy/coherency” and/or “usefulness.”

- Lastly, any recommendations on changes/tweaks are definitely welcome!

---------

Footnotes

1. This source in particular (https://mdickens.me/2016/06/10/evaluation_frameworks_(or-_when_scale-neglectedness-tractability_doesn't_apply)/) does try to provide an alternative framework for focusing on decisions rather than problems, but they take an approach that I think might work better when used within the stock issues framework (e.g., finding evidence through the lens of / to fulfill each of the stock issues), rather than vice versa or just plainly not using the stock issues’ framework’s reasoning.

2. In retrospect, especially having read more about some of the frameworks and their purposes, I suppose that this may not be a full alternative to the INT framework, but I’ve since figured it is related enough to warrant some response.

3. Upon finishing this, I realize I might have failed this goal.

4. One of the most notable differences between the formal and informal frameworks is the division between inherency and significance: if they even bother making the distinction explicit/clear, many debaters will tend to treat significance as including “descriptive causal” claims in addition to “end normative” claims. For example, they may say “The inherency is that we currently have a tariff in place. The significance is that the tariff causes economic harm (which is just obviously bad).”

5. I and many other people including coaches have pointed out that this is not what the word “solvency” means in common/non-debater usage, but it’s stuck very well in leagues (especially among high schoolers who have never used the actual meaning of the word), so it’s what people say.

6. When this is taken very literally, it seems that significance could start to ontologically shrivel up in relation to inherency, given that someone might be able to technically say “You say the status quo leads to economic harm, but is economic harm inherently ‘bad’? Causes people to die, you say? But is that inherently bad? Suffering? What even is suffering but chemicals/neurons producing a factual state in someone’s mind?” This is part of the reason why I (and other debaters, perhaps unwittingly) tend to use significance in the more informal sense, as mentioned in a previous footnote.