In the effective altruism movement it's common to break things down into three general approaches:

- earning to give: earning more so you can donate more, using this money to fund things you think are really important.

- direct work: spending your working time doing something useful, not mediated by money.

- building career capital: doing something that isn't valuable for itself, doesn't make you much money that you can donate, but is focused on preparing you for future direct work or earning to give.

For example, my working as a programmer so I can donate money is earning to give, while when I was briefly working full time as an independent researcher that was direct work. My time in school was primarily about building career capital, though I wasn't thinking about things in an EA way at that point.

I've been thinking about how these choices interact with paying for college for your kids, and especially the financial aid system.

Fancy colleges use a very powerful system of price discrimination. They set their price very high, but don't expect most people to pay the sticker price. Instead they have a financial aid system where they collect as much information as possible about each family's financial situation, estimate the most the family would be able to pay, and then charge that. About twenty top schools are rich enough to charge exactly what they think you can afford (meet 100% of demonstrated financial need without loans), while about another ~10 will do this for families with income under a threshold, and another ~45 will include student loans in the price (meet 100% of demonstrated need, with loans). Here's a list of these schools.

If you don't have so much income or assets that the college will expect you to pay the full amount, you can think of these as a 100% tax on your post-tax income: earning $1 more means the college will charge $1 more.

This pushes very hard in favor of direct work over earning to give. If I earn $200k after tax and donate $150k, the school still sees that $150k as money I could pay them. Even though I only took the high earning job so I could give the money away, that's not how the school would see it. On the other hand, if I took a direct work job paying $50k after tax I would be in a similar place in terms of effective income, but the school doesn't make a claim on the income I'm passing up.

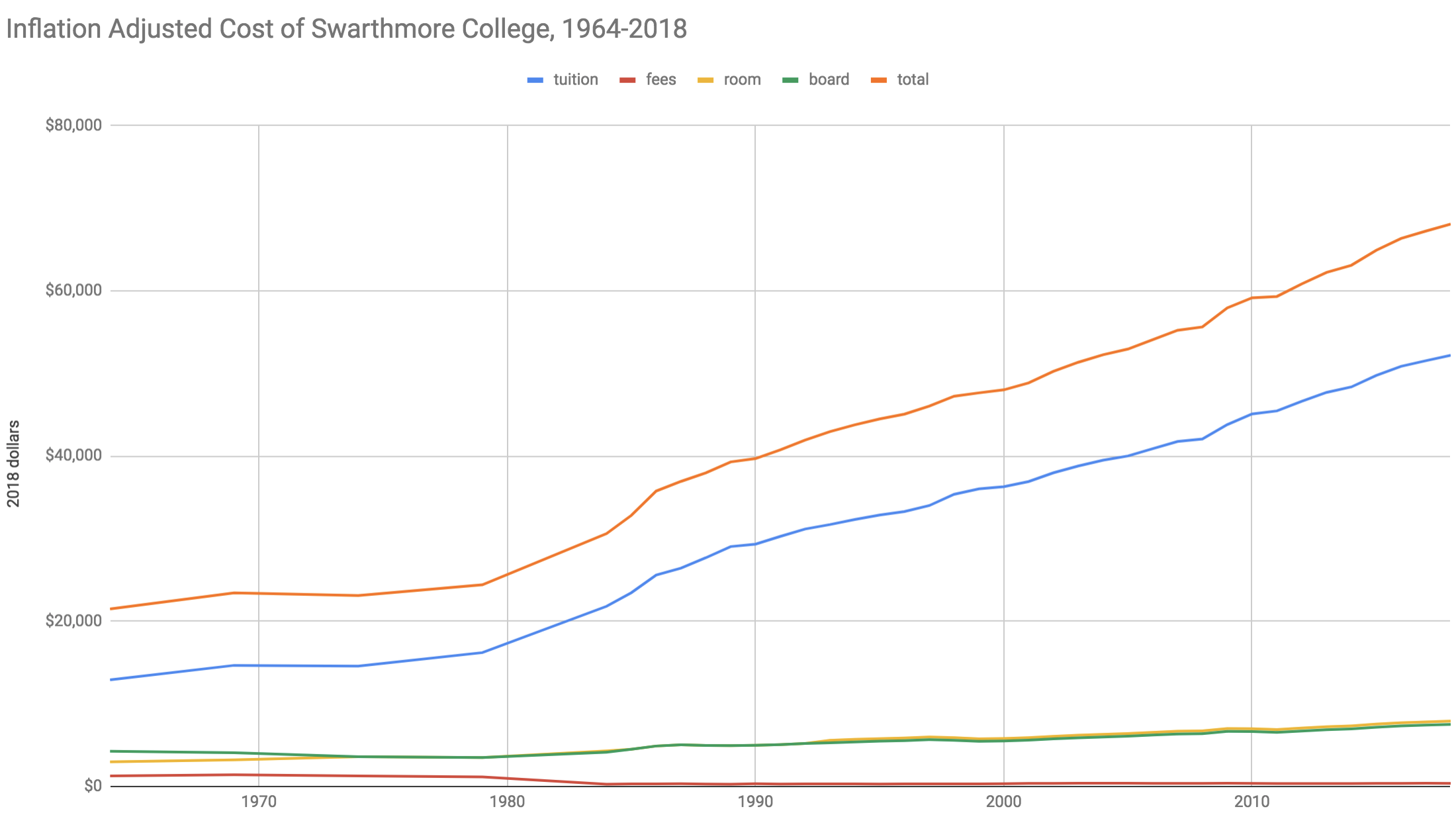

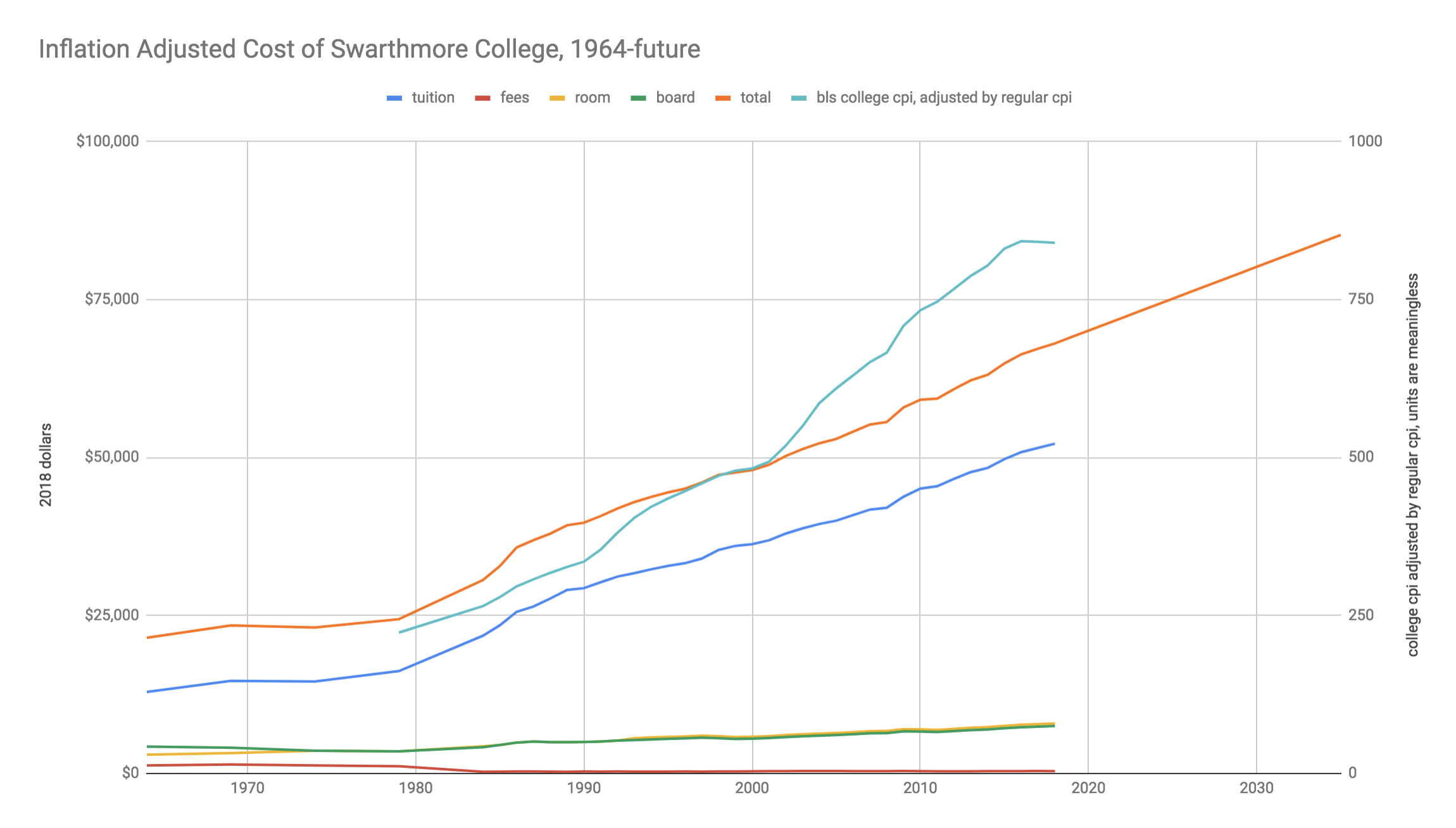

Before we can get into figuring out approaches, though, how much is college likely to cost? My kids are two and four, so let's say the mid 2030s? Let's start concrete and look at how prices have been changing at the college I went to (Swarthmore), adjusted for inflation:

Looking at that chart, the main thing that comes to mind is to wonder what changed in the early 1980s? Why did costs suddenly move from increasing at about the same rate as inflation to increasing so much faster? I've read some things suggesting this is colleges hiring many more administrators, but I'd be really curious to read more if people know what's happening here? I'd also love to see two similar charts, one showing the amount students actually pay, after financial aid, and the other showing college expenses per-capita, since fundraising is also a large source of college income.

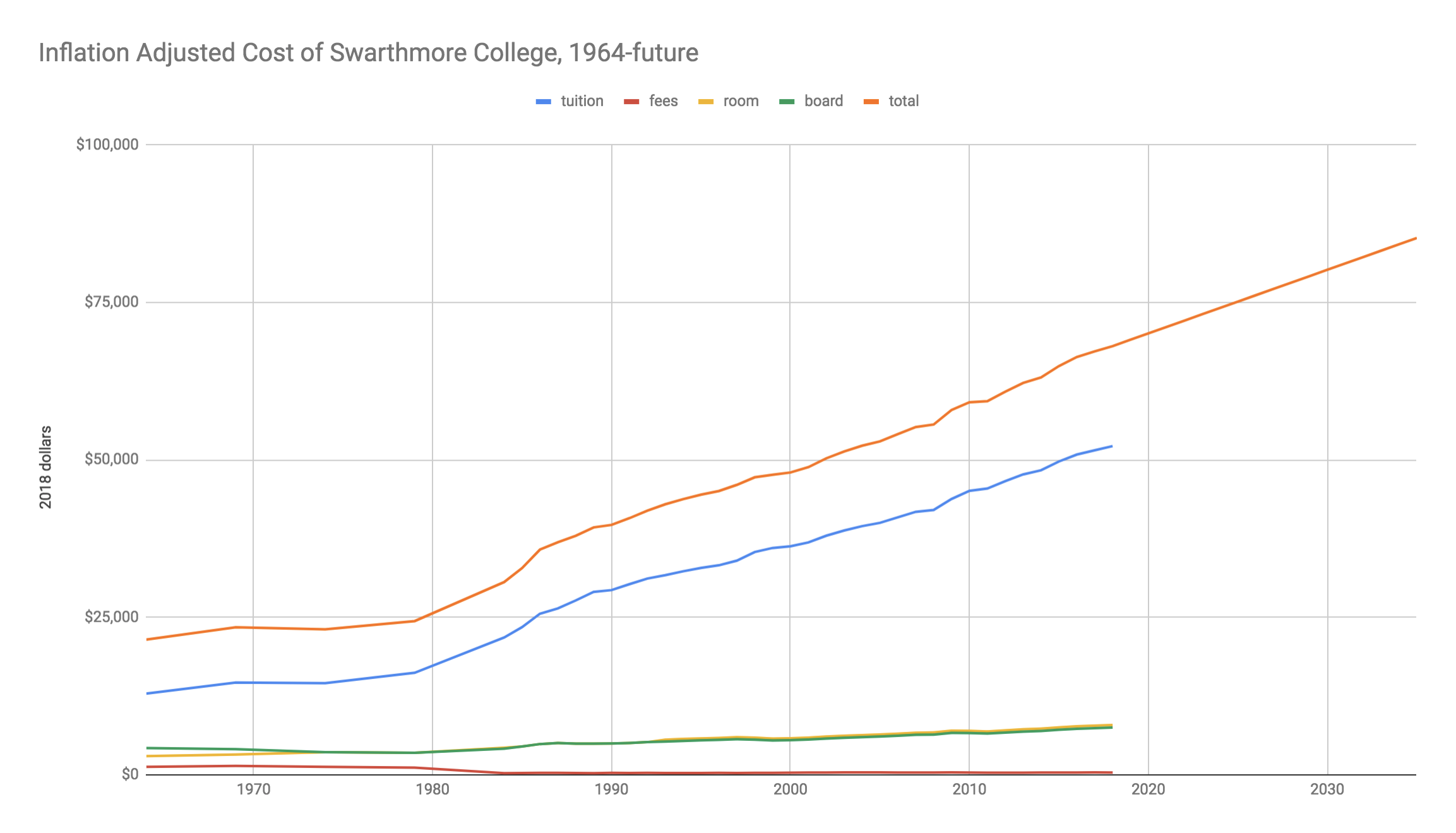

While understanding the growth in costs more would be useful in trying to predict it, the slope is remarkably steady going back to that bend in the early 80s. Averaging over the 1986-2018 period, costs have been going up $1,009 per year in 2018 dollars. Naively extrapolating you get:

This would give estimates, still in 2018 dollars, of $82k for when a now-four year old starts college, and $87k when a now-two year old finishes.

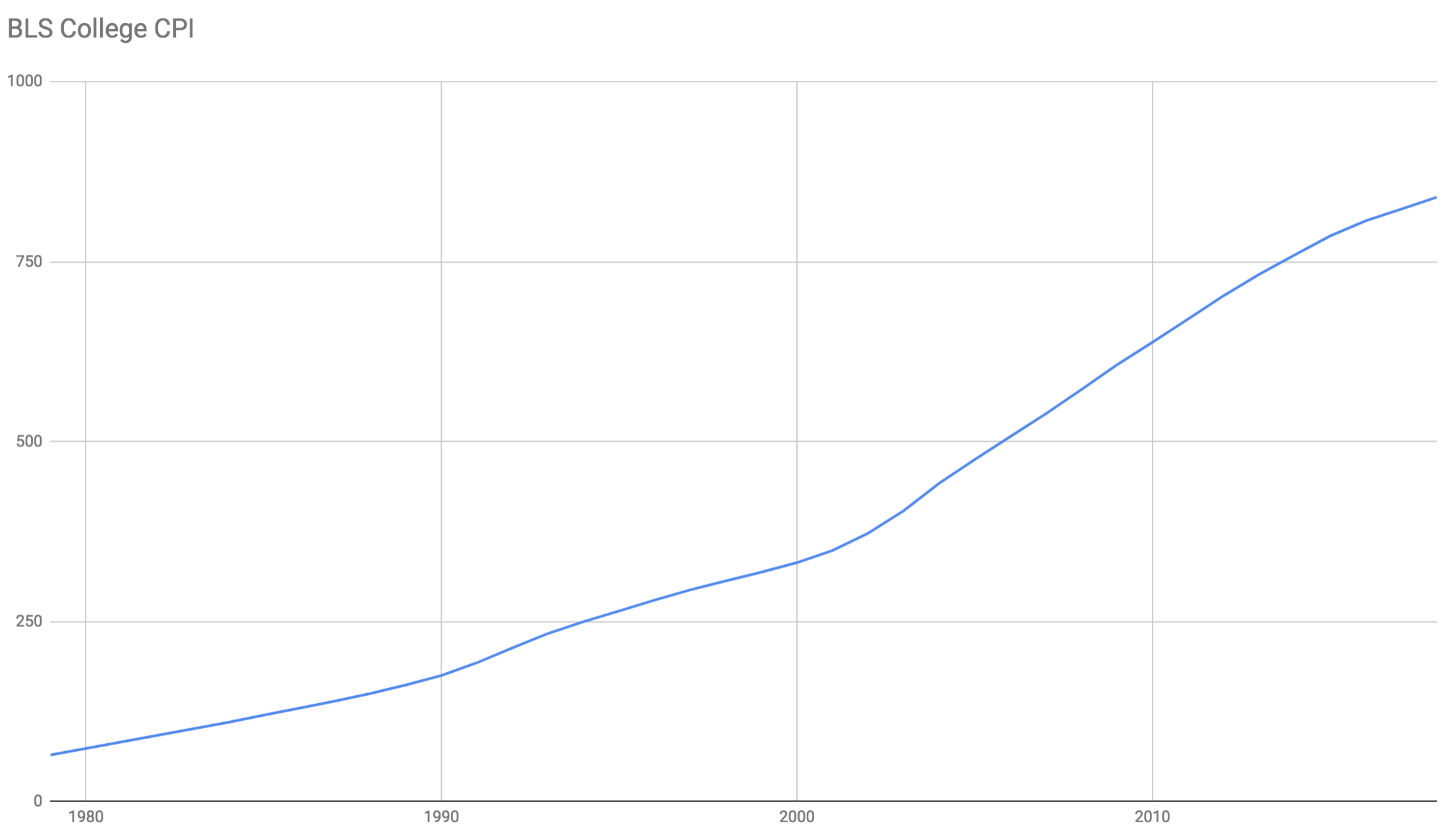

This was much less of an increase than I was expecting to find! If you look for a cost of college graph you often find things like:

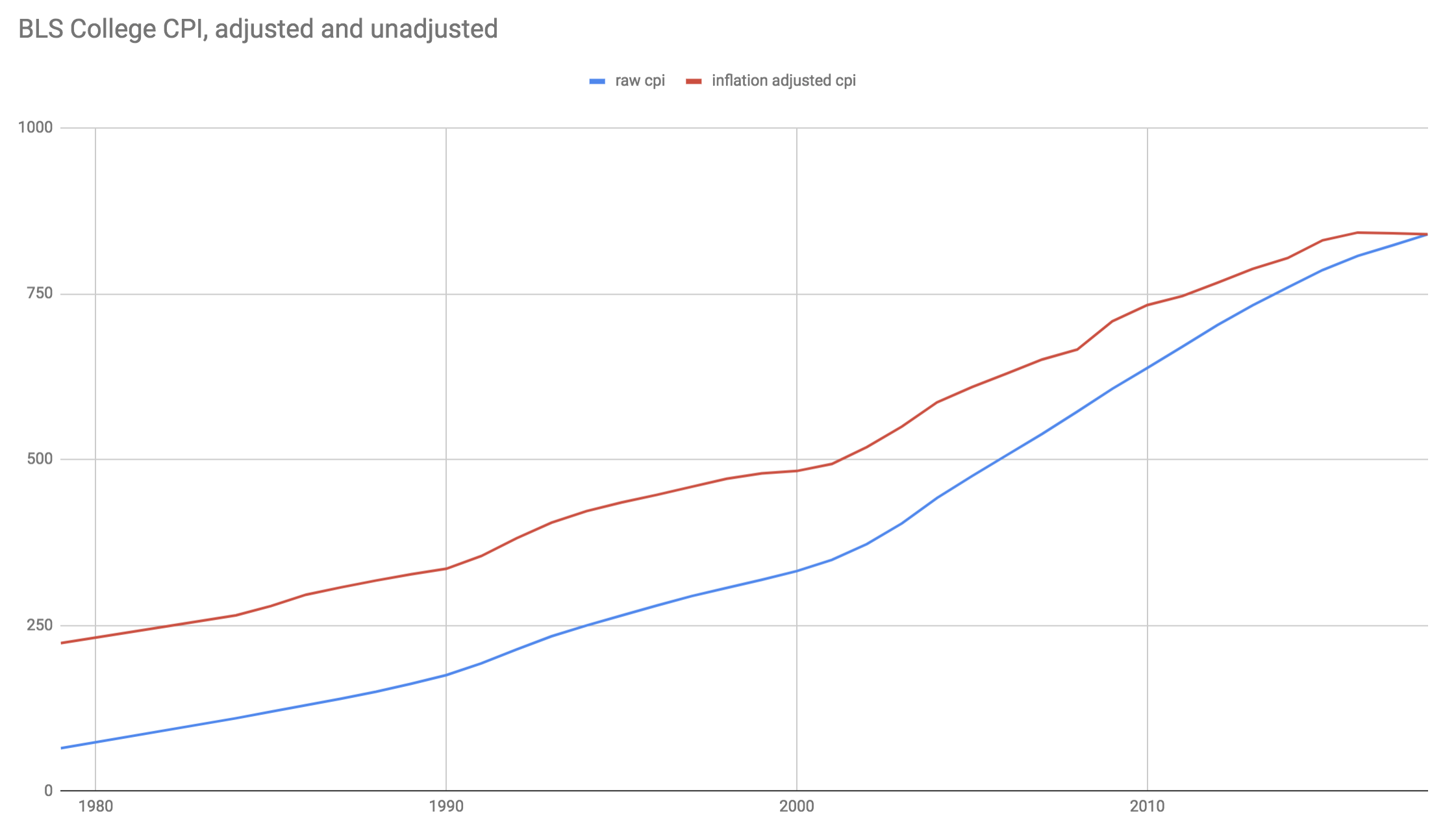

This is graphing the BLS College Tuition and Fees consumer price index, which tries to track the cost of college. This shows college cost rising much faster than above, because it isn't adjusted for overall inflation. What if we adjust this for inflation, the same way we would convert past dollars to present dollars?

This is still a faster increase than we saw with Swarthmore. Let's put them side-by-side:

If Swarthmore's costs had grown at that rate it would have moved from $16k in 1986 ($36k in 2018 dollars) to $101k in today, instead of the $68k we actually see. That's 2.8x instead of 1.9x.

I think what's going on is that Swarthmore was already a very expensive place, while most of the schools in the CPI started off much cheaper. While I haven't looked at numbers for the other schools at the top of the price range, I'm pretty sure I'd see the same thing: large cost increases, but not as fast as the college CPI.

Are there other factors affecting cost? For the most expensive schools, with their financial aid-assisted price discrimination I think there's not much of a downside to continuing to increase the official price. A larger and larger fraction of people will be on financial aid but, since these schools are careful not to charge more than the families can pay, higher prices probably don't end up turning people away. I'm not sure what keeps the colleges from raising their prices even faster, but my guess is that they want to avoid looking greedy. This makes me think $80-90k/year in 2018 dollars is a pretty good guess for schools at the upper end of the price range in the 2030s.

Now, there are lots of other ways things could change by the 2030s. College could lose its relevance as top employers start recruiting promising high school students. The idea that everyone should go to college could fade for some other reason. Colleges could be "disrupted" by something else that can fill a similar role in a much cheaper way. Or colleges could become even more central, even more competitive, even more able to use high sticker prices as evidence of the value they provide, financial aid loses its remaining stigma, and sticker prices could rise faster. Or there could be some kind of collapse or disruption, where this all looks very different. I'm going to try looking ahead assuming stuff doesn't change, but also avoid giving recommendations too tied to the current way things work.

(It's also possible that our kids won't be strong academically and so not a good fit for college, especially the top colleges I'm talking about here. We'll know much more about what they're like closer to the time, and can adjust then.)

First, whether this is worth caring about at all depends on how much money you're making. If your income is $1M/year, you probably do well to continue earning to give even if colleges are taking $85k. On the other hand, if I'm making closer to $300k then after taxes and college there would be very little left to donate. It's very hard to predict how the market for software engineers will look that far out, and I think there's a decent chance my income will fall substantially, but I'll keep going assuming it stays in this range.

So even if I'm a much better fit for earning to give than direct work, I might want to move out of earning to give when my kids are getting close to starting college. Because colleges look at ~2 past years income when making current aid determinations, this transition would need to happen a few years early. Closer to the time I'd want to look into aid determinations again, to make sure I didn't stick with earning to give too long.

I'm guessing my two kids will be in college for a combined six year span, so this would mean at least eight years away from earning to give. One consideration is whether I'd be able to move back into this after being away for so long. It might be worth having six years of not being able to donate 50% in exchange for the years after being much more productive. I think this depends a lot on what I do in the intervening time. For example, if my direct work were in tech of some kind I'd still be getting relevant practice, whereas if I did this as more of a career change it would make more sense if it wasn't something I would be switching back from.

Another possibility is that I could continue earning to give, and our kids could go to a cheaper school. I don't know what that's likely to look like in the 2030s, but if I were deciding this today my guess is that it's worth it for our kids long term to go to the best school they can get into. It doesn't take very many years of higher income alone to make up the difference.

I also looked some into the best ways for parents to save money if their kids would be getting financial aid. While I previously suggested students get married so their parents' finances wouldn't be considered, schools that do this kind of price discrimination request the CSS Profile in addition to the FAFSA, which does include finances for parents of married students. Details of how this works are likely to change, but it looks like retirement accounts are pretty much the only place you can reliably put money and not be expected to use it to pay for your kids' college. Retirement early withdrawal is a 10% penalty, and schools typically take 5% of assets per year, so it makes sense to put money into retirement accounts even if you think you might need it before you retire.

It looks like saving money for college in a 529 plan, especially one in the student's name, is not a good idea. The more you save the less financial aid you get, though not with at high a rate as with income: the CSS Profile currently figures 5% (per year) for parental assets and 25% for student assets.

College is still a long way off, with my kids yet to start kindergarten, so it looks like the only two take-aways right now are that it's not useful to safe explicitly for college and that retirement savings accounts are good. Look for an update some time around 2028.

cross-posted from jefftk.com

I enjoyed this very much.

I would love to see a paper actually breaking out how all the reasons why college has gotten so much more expensive actually contribute quantitatively, but I have not seen it yet. In general, we expect something that is labor dominated to increase faster than inflation, because salaries increase faster than inflation (this is roughly per capita economic growth). But college has increased faster than per capita income. You mention more administrators. Also, there are more services, like career services. You point out that tuition has increased faster than the amount actually paid, because there is more price discrimination. There is also reduced state funding for state colleges (I believe absolute and definitely as a percentage). There may be reduction in mean class sizes-there has been for primary and secondary. There is more technology use inside and outside the classroom - overall I think this has increased efficiency, but it would still probably show up as an increase in tuition. On the side for controlling costs, a much greater proportion of classes are taught by low-paid adjuncts. Also, terms have gotten shorter. Another factor that can control costs is endowments. Princeton has actually reduced its tuition recently because its endowment is so big.

I've also heard that a strategy is to have your kids get adopted, but as I look into it I'm not sure why this would work, as it seems the CSS profile would then look at your child's adoptive parent's assets. I guess you could have your children be adopted by someone with low income/assets. (I'm also not sure if this strategy is legal)

Combine this with the destitute medicare strategy, and have them adopted by grandparents: https://www.jefftk.com/p/adapting-to-means-testing

Or let them pay for their own college. The rates they'll get charged will take your income into account, so they'll have to get a lot of loans. But the loans are pretty manageable and essentially risk-free as long as income-based repayment remains an option. Now, if they are committed EAs and will be earning to give, this doesn't accomplish as much since this comes out of their future earnings. But even if there's a 95% probability that they turn out to be earning to give as EAs, that's still better than the ~100% odds with respect to you. And the interest rates on those loans are lower than average stock market returns, so the smart financial move is always to get the loans and pay them off as slowly as possible rather than pay higher up front costs (assuming they're reasonably risk tolerant, as young people should be but especially when the goal is to maximize good done rather than maximize their own comfort) (this is a little more complicated to see when we're talking about earning to give. but you must be assuming a larger discount rate for the value of donations than what you could earn by investing and giving later; otherwise you'd be doing that instead of giving now. So if giving the money away now is worth sacrificing the ~10% annual gains you could make on it, then it's even more worth sacrificing ~7%/year in interest payments).

I agree it is good to think about it early! The 529 still can be better than general taxable savings because of a tax deduction and then tax-free growth. The problem is limited investment options. However, the Coverdell has more freedom of investment, so I'm doing that. Depending on the college, faculty or even staff have their kids go at reduced or free tuition, which could be an option for some people. That is a creative idea to do direct work while kids are in college. If one does have significant savings by then (including retirement savings, because as you point out the penalty for withdrawal is not that large), one could even take off time from paid work. This is facilitated by being able to take out an interest free loan on the part one does not have to pay right away while the kids are in college. Or if one is doing direct work while kids are in college, one could just continue the direct work afterwards. Since parents are expected to pay 5% of taxable assets per year when in college, I believe that means one would need to pay about 30% over six years. As you point out, there is also uncertainty that it would even be required (like if MOOCs take over). But you can still think of this (and the interest free loan) as an additional reason other than avoiding taxes to donate more money now instead of accumulating it in a taxable account. (Disclaimer: I am not a financial advisor nor a tax professional.)

This post describes part of the cost of college as a "100% [marginal] tax on your post-tax income". Have you seen other financial-planning and -optimization resources mention this and deduce things from it (whether in an EA context, as you have done, or not)?

There are lots of financial planning resources online (including at places you frequent like lesswrong), and many of them discuss saving for college. But it seems like people generally appear to have missed a minus sign on the utility of saving for college (in certain situations, as you describe). For all the words people say about, say, how HSAs are the best investment vehicle available, they don't seem to say as much about how financial aid works at high-end schools. I'd be especially interested in anyone who's competent enough to run a simulation with this factor in mind.

I haven't seen other resources that talk about the cost of college this way, but I also don't spend much time looking at financial planning advice?

The approach in this post is only relevant to a pretty small fraction of people:

I think this is likely enough that a 529 plan or similar does not make sense for our family, but I'm planning to revisit when my kids are getting close to high school (and I have a better sense of their academic standing) before considering a career change.

Thanks for your response.

I think it's slightly more general than you suggest, because the "tax" is so high. For example, if you're trying to decide whether to buy a larger house or invest the difference in a 529 plan, it could be a better idea to buy a larger house.

I went to one of these schools, and my parents noted at the time that under the right circumstances, they might have saved money by buying a fancy car "instead of" saving for my college.

This is a great article! Given the extremely high cost and demanding debt structure of college in the US, do you think that those of us who are lucky enough to live in countries with free, cheap(er) or more easily paid-off college tuition, should remain in those countries at least for undergrad (while aiming for top world colleges if/when we do a PhD)?