Summary

- Bivalve aquaculture increases population health, increases food security, improves developing country welfare, benefits the environment, mitigates climate change, and improves animal welfare.

- There is enough availability of suitable coastline to support at least an order of magnitude more production.

- Bivalves are significantly more expensive than meat, and the demand curve can absorb large increases in supply.

- There do not appear to be any intractable problems preventing significant expansion.

- Increasing production can be financially risky, which is why we have less bivalve production than is optimal.

Bivalve aquaculture means marine farming of scallops, oysters, clams, mussels, and similar. We will be focusing on these four because they are the largest production share of edible bivalves. In contrast to intensive fish aquaculture, bivalve aquaculture is an extensive form of aquaculture; bivalves feed on algae that occur naturally in the ecosystem and no additives such as vitamins and antibiotics are added.

It has multiple benefits, the main ones being developing country welfare, food security, climate change and environmental benefits, and animal welfare. These will be described fully in their respective sections.

Bivalve aquaculture is one of the most promising interventions but not the top one along each of these dimensions. For example, Allfed approaches it from a food security perspective, finding that it is worth further research based on this alone. Tren Griffin is interested in it for its positive impact on climate change.This positioning means that it falls between the cracks and is not prioritized. Indeed, a search for the term “bivalve aquaculture” on the Effective Altruism forum did not return any relevant hits apart from my draft post on this topic.

We should prioritize this cause area because its combined benefits mean that it is an intervention with very high impact.

This is an initial look into this cause area; approximately 35 hours was spent on research and on “shallow” introductory discussions with people interested in this idea.

Note: The preliminary idea for this submission was previously posted here. This post contains additional research and supersedes the previous post.

Bivalves are the most preferred protein source

Epistemic confidence for this category: high

People mostly love the taste of scallops, oysters, clams, and mussels. In some areas of the world, such as most of East and Southeast Asia, they are considered to be highly prestigious luxury foods. They are also desired in South America and many parts of Europe. Bivalves are less popular in North America, and so we would expect North Americans to underestimate the desirability of bivalves as a food.

Here is a brief overview of how these bivalves are seen:

- Scallops are universally loved: “Even people that don’t naturally enjoy seafood eat scallops. Because of the rich taste, it is a best seller.”

- Oysters are polarizing. A significant proportion of people hate oysters, while many others love them. This is fine for bivalve aquaculture potential because the oyster-haters don’t matter – current production levels of 6 million tonnes per year (in 2018) represents less than 0.2% of total food production of 4 billion tonnes (2020), and increasing production even by an order of magnitude wouldn’t dent the demand curve.

- Clams are popular, and especially popular in Asian cuisine: “Clams are delicious, and what they taste like will depend on the time of year.” Even people in the United States are familiar and accepting of clams, such as in New England clam chowder. Their relatively neutral taste makes them versatile.

- Mussels are slightly less popular because of their inferior texture, but are still considered yummy: “What Do Mussels Taste Like: Yummy or Yucky? They are super healthy yet yummy at the same time.”

In most parts of the world, seafood is more highly valued than meat like beef, chicken, or pork. When available, seafood readily substitutes for meat, and the main obstacle is that seafood is more expensive. For example, here is a typical Chinese wedding banquet menu that has three options. We compare the cheapest one with the most expensive one.

To make it easier to compare, we cancel out identical items and ignore the non-meat or seafood ones, and categorize them as “meat”, “seafood”, or “bivalve”.

The cheap option includes pork and chicken. The expensive one contains seafood and bivalves. This implies that most people like the taste of bivalves more than meat, as shown by their willingness to pay extra for it. If we were to substantially increase bivalve production, it would mostly substitute for a lot of other protein sources, mainly beef, pork, and chicken – we do not need to worry about a demand deficit or a lack of substitution effect.

How big is the opportunity?

Epistemic confidence for this category: high

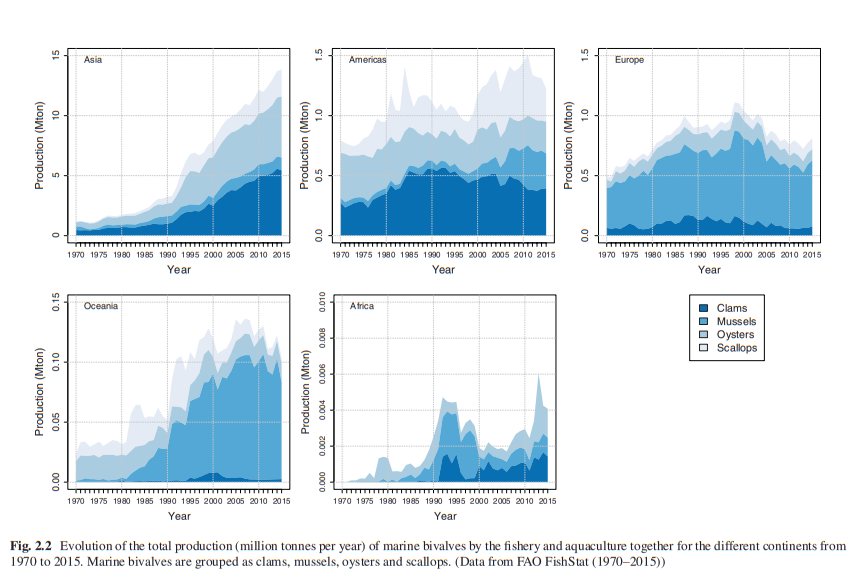

The global production of marine bivalves for human consumption is more than 15 million tonnes per year (average period 2010–2015), which is about 14% of the total marine production in the world. For a ballpark comparison, total food production was 4 billion tonnes in 2010. Most of the marine bivalve production (89%) comes from aquaculture, with a total economic value of 20.6 billion US$ per year, and only 11% comes from the wild fishery. Asia, especially China, is by far the largest producer of marine bivalves, accounting for 85% of the world production and responsible for the production growth.

Here is a breakdown of production by type of bivalve, and by continent, as a time series:

Bivalves are more expensive than farmed animals at the moment. For example, retail prices at my local supermarket for fresh food are:

| Scallops | $49/kg (Australian dollars) |

| Beef | $28/kg |

| Pork | $18/kg |

| Chicken | $13/kg |

We observe a large price gap between scallops and other meat. Combined with the small current bivalve percentage of total food production, this implies that a large increase in the supply of scallops would meet ample latent demand at a good market-clearing price. This intuitively makes sense, since bivalves are the most preferred protein source as shown in the previous section.

Seasonality is another potential concern. If bivalves are only available for a few months of the year, then demand would be harder to match to supply.

Oysters are usually seasonal but can be farmed to be year-round: “Perhaps the best reason to only buy oysters during the fall, winter, and spring—the "r" months—is related to the creature's reproductive cycle […] a new genetic procedure being used by some commercial oyster farms renders farm-raised oysters sterile, so they don't spawn at all. These prime oysters are available for year-round enjoyment.”

Clams and mussels share the same seasonality as oysters, but are less sensitive: “Clams and mussels do lose quality in months without R, but not as noticeably as oysters.” Scallops also have similar seasonality, but I wasn’t yet able to find supporting evidence.

All bivalves can be cost-effectively snap frozen for transport and for future use, with a small loss in quality. This reduces the seasonality effect significantly.

Lots of room to scale

Epistemic confidence for this category: high

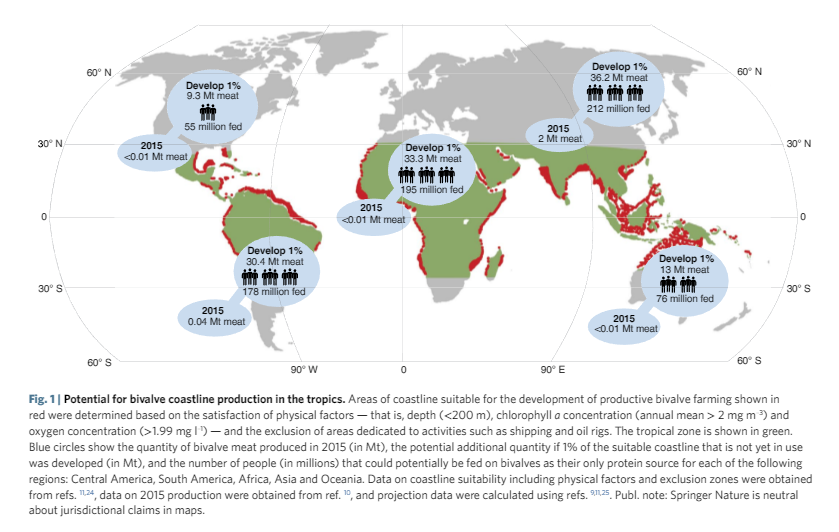

“Across the world there is an estimated 1.5 million sq km (579,000 sq miles) of coastline suitable for growing bivalve shellfish. According to Willer, developing just 1% of this could produce enough bivalves to fulfil the protein requirements of more than one billion people.”

The July 2020 article in Nature by Willer maps out tropical regions that are suitable for bivalve aquaculture. These regions contain a majority of the world’s population:

It’s possible that some of this coastline is located in areas with bad governance, and that not all of these places would be accessible or economically viable. But this is a tractable problem which can be ameliorated with new technologies and support, and shows that room to scale is unlikely to be the bottleneck.

Additionally, the gradient of scaling is also satisfactory; for example, “There is a high potential for expansion of mollusc farming in the ASEAN region as an alternative economic activity for small-scale fishermen.” Incremental effort has a proportional benefit, so a bootstrapping approach transitioning into larger scale action is viable.

If we look at bivalve aquaculture using a “startup” lens, the blue sky scenario is encouraging, with a huge “total addressable market”. Serious long-term efforts are unlikely to be wasted.

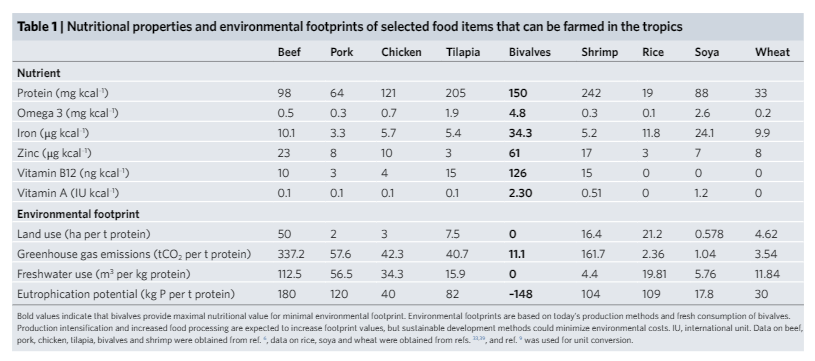

Health benefits

Epistemic confidence for this category: very high

All bivalves are highly nutritious and healthy:

- Oysters are high in protein (9.5g protein, 2.3g fat, 5.0g carbohydrates per 100g), and contain micronutrients including zinc, B12, omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, iron, and magnesium.

- Scallops are even higher in protein (20.0g protein, 0.8g fat, 5.2g carbohydrates per 100g), and contain omega-3 fatty acids as well as magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, selenium, B12, and choline.

- Clams are also good (25.5g protein, 2.0g fat, 51.g carbohydrates per 100g), and are excellent sources of iron, zinc, selenium, and B12, as well as other micronutrients.

- Mussels have 11.9g protein, 2.2g fat, 3.7g carbohydrates per 100g, and provide B12, selenium, manganese, omega-3 fatty acids, and iron.

Here is a summary, calculated for tropical regions:

The main risk factor for bivalves is heavy metal accumulation when their water is contaminated. For example, scallops and oysters can contain cadmium. This says that cadmium is the main heavy metal risk for bivalves, but it is more concerned about fish as a bioaccumulator. This paper gives a relative ranking of heavy metal contributors, saying that “The total THQ (TTHQ) values were 0.88 for vegetables, 0.57 for cereals, 0.46 for meat, 0.32 for fish, and 0.07 for fruits.”

Since fish is riskier than bivalves, and vegetables, cereals, and meat are more serious than fish, my understanding is that bivalves are significantly safer and healthier than other foods. Commercial farming involves a “depuration” stage, where bivalves are held for a minimum of 48 hours after harvest in clean water, but farmers might be tempted to skip this step, depending on the incentives involved. However, the magnitude of this harm should be small, since bivalves are near the bottom of the food chain. Therefore, increasing bivalve production, particularly in developing countries, would have a multiplicative benefit as it would not only provide food security and economic value, but also health benefits.

Food security

Epistemic confidence for this category: high

Bivalve aquaculture can help with food security, as it makes our food supply more resilient. Quoted from JuanGarcia at ALLFED with permission:

Bivalves can be grown in sinergy with seaweed in what is know as integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) systems, which promise a consistent feedstock, in situ, with the co-benefit of recycling aquaculture waste (ref). They are also resilient to food trade restriction and the pests that affect land crops. They look like they could be significantly more resilient to changes in climate than land crops, thus being useful to counter falling agricultural yields in two ways like most resilient foods: 1) resilience - the higher the production of this food is prior to an abrupt food production shock, the smaller the overall fall in food production capacity, 2) response - the fall in agricultural yields could be countered by rapidly scaling production of this food post-catastrophe.

These are the things that we have yet to ascertain though. Uncertainty remains, but there definitely seems to be potential for bivalves and IMTA to compete in price and speed with other resilient food options, indeed contributing to a resilient food portfolio. It mostly depends on how growth rates would be affected by changes in climactic conditions. Because bivalve cultivation is not very complex technologically it looks like it could not only contribute to resilience and response against global catastrophic food shocks involving an agricultural collapse, but also those originating from a loss of critical infrastructures.

Developing countries

Note: Epistemic confidence is low; more research needed to quantify the impact size.

It’s quite likely that bivalve aquaculture can have an enduring positive impact on developing countries. This report claims widespread benefits in Vietnam, for example: “There exists an opportunity to rapidly advance and sophisticate oyster aquaculture in Vietnam by exploring the full economic potential that has environmental, social, and sustainability benefits.”

Even if distribution isn’t developed enough for export, bivalve aquaculture can still provide highly nutritious food locally, as mentioned in the previous section.

Another potential benefit is “protein lock-in”: all countries increase their protein consumption as they become more prosperous. If we manage to influence protein preferences during the growth phase, we can lock in the proportions so that bivalves make up more of the consumption. This makes the demand for bivalves strong and sustainable, while bringing the benefits discussed in the rest of this report.

I think that a correctly implemented plan would have very low risk of causing harm. The main risk to watch out for is whether the bivalve farms displace already-existing activities. This requires sensitivity to local conditions, but no more so than for any other intervention in a developing country.

Environmental benefits and climate change

Epistemic confidence for this category: high

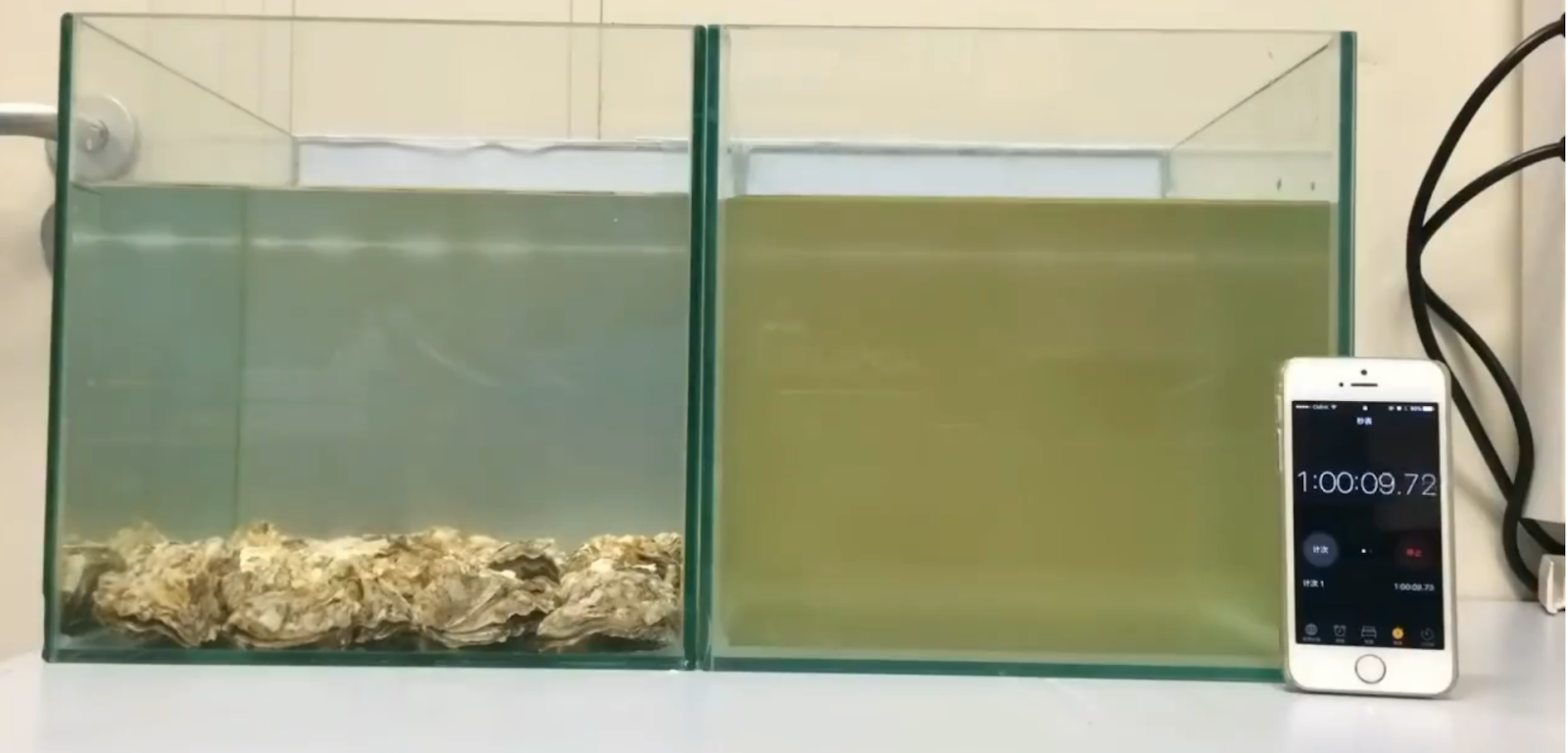

Bivalves are great for removing algae, and can clean up polluted water. Here is a fascinating time-lapse video of oysters in action!

They also provide coastal defense and increase biodiversity. We do need to be careful of unanticipated consequences because it changes the marine ecosystem, but the consensus seems to be that the risk is limited and the overall effect is almost certainly positive.

Bivalve aquaculture can also ameliorate climate change: “Marine bivalves [...] sequester carbon in their shells as calcium carbonate and may be used to mitigate the effects of climate change.”

See also: “The animals that are the source of this food require no feeding, need no antibiotics or agrochemicals to farm. And they actively sequester carbon.”

Some effective altruists place a lower priority on climate change because there are many other causes that are less in the public eye, but no less important. However, since many non-EAs think of climate change as a very high priority, we could emphasize its positive effect in order to gain allies for more effective operations and impact.

Animal welfare

Epistemic confidence for this category: medium

Eating bivalves causes less suffering than an equivalent amount of chickens, pigs, cows, and most other animals. Depending on what it substitutes for, it would also reduce crop farming and associated rodent/insect deaths, which are more sentient than bivalves.

Bivalves have a simple nervous system with usually three sets of ganglia connected by nerve fibers. Ganglia are clusters of nerve cells that form simple nerve centers distinct from the brain. They do not have brains (i.e. a central nervous system). For a neuron count comparison, small clams have around 6,000 neurons. Garden snails have around 60,000 neurons in their whole nervous system. Aplysia (sea slugs) have around 18,000 neurons throughout their nervous system. For reference, common octopuses have half a billion neurons throughout their nervous system, and dogs have 2.25 billion.

An absolutist approach would require not eating bivalves because there is still uncertainty about bivalve sentience. On the other hand, a practical approach would focus on the alternatives. For most people, the alternative to eating bivalves is to eat meat, so we would be trading an uncertain and unlikely possible harm for an immediate, certain, and large harm; most people are receptive to a proposal to substitute bivalves for other meat, but are not receptive to proposals to go vegetarian/vegan.

Another potential substitute for meat is plant-based meat. Bivalves are far healthier than current plant-based meat alternatives, which have minimal health benefits: “Diets based on novel plant-based substitutes were below daily requirements for calcium, potassium, magnesium, zinc and Vitamin B12 and exceeded the reference diet for saturated fat, sodium and sugar.”

How tractable is it?

Epistemic confidence for this category: fairly high

Increasing bivalve production appears tractable: “Bivalve aquaculture has proven highly successful in Vietnam. Species are easy to farm and require low-level skills, training, and technology to produce healthy and conditioned animals that are nutrient-packed and ready for the local markets and tourists. Previous ACIAR investment in Vietnam has supported the establishment and rapid growth of the edible oyster industry, which is now thriving, and demonstrates just how important this industry now is as a reliable and nutrient-packed food source.”

Another data point: “Production costs are also relatively low, making bivalve farming an accessible venture for both large businesses and also small-scale farmers in the developing world. The economic viability of bivalve farming in a rapidly developing nation has been proven in China, which began extensive bivalve farming in the 1950s and now yields over 85% of global production.”

It appears that this is a surmountable problem. This Nature article is high quality and has more explanation of the hurdles preventing increased bivalve aquaculture: “To meet and expand its potential, the bivalve industry in tropical regions requires development across the entire value chain. As discussed below, major challenges must be overcome across hatchery, grow-out and depuration stages of production, as well as in infrastructure and consumer marketing — but innovations and technologies can turn these challenges into exciting opportunities for success.”

I note that the two successful examples, Vietnam and China, are countries with high state capacity. This is likely because the lead time required to develop bivalve aquaculture is quite long, from hatchery to grow-out. For example, oysters can take 2 years to mature. This would require significant working capital. Large amounts of capital could also be needed for building out supporting infrastructure. These constraints have useful implications for where EA work on bivalve aquaculture would be the most effective.

Bivalve aquaculture has tail risk: “There are a ton of tail risks that can go wrong and wipe you out. Big one is disease, and the bigger the scale the harder that problem is. A lot of unknown unknowns.” “Intensive aquaculture is tricky, diseases and anoxic conditions can wipe out entire crops.”

The combination of tail risk and long lead time means that we’d expect bivalve aquaculture to be systematically underfunded, especially in developing countries with weaker state capacity. This means that it is a great candidate as a funding cause: both risk capital and investment capital are valuable. It also means that we can be creative in how we approach spending money. For example, paying for insurance policies might be as impactful as investing directly.

Who is already working on it?

I haven’t talked with experts in the field, and would love to find out more about this. This is a high priority area for additional research, in order to “catch up” to the knowledge frontier. Important sectors would include:

- Industry bodies

- Universities and marine biology institutes, for research

- Government agricultural agencies, for development

- Philanthropic establishments already active in the area

Next Steps

Epistemic confidence for this category: medium

Bivalve aquaculture is a high impact cause that has multiple benefits, is robust to evaluation errors, and is neglected because of its “jack of all trades” positioning. It is a high priority for additional research and funding.

The following sequence might be a sensible path forward:

- Catch up to the knowledge frontier, in order to efficiently learn about the current state of affairs.

- Conduct a feasibility study to make sure that the benefits described above are real, and to work out whether there are any downsides that we haven’t discovered.

- Discover which area of the bivalve aquaculture production cycle is the bottleneck.

- Work out what kind of funding approach or intervention would be the most effective.

I appreciate the effort you've put into this and I hope in this comment I don't discourage this sort of investigation. I think it is laudable and valuable, and I hope you continue doing research on potential cause areas. That said, there are several assumptions this works off of that I think are at best questionable, if not outright incorrect. Some of these were noted in the comments of your earlier post, but do not seem to be addressed in this updated version. I am concerned by this given the potential significant harm of EAs adopting bivalve farming as something to champion, as well as the inaccurate claims this post perpetuates. I won't address all of these issues in this comment, but I'll try to go through a few of them:

From your writeup:

You appear to be comparing different animal menu items against each other, rather than sources of protein. Globally, looking at consumption by grams of protein, plants continue to comprise the largest category in people's diets (Our World In Data). From your writeup, I don't see evidence that bivalves are the most preferred protein source; I see some indication that bivalves are sometimes viewed as a luxury food.

Is there a citation for this? And if this is correct, what animals are the primary alternative and what plant foods were presented as alternatives?

The claim you are making here is not backed by the linked source. The linked source shows that people are going vegetarian/vegan, but retention is the issue. What is the source behind the claim that people are receptive to substituting bivalves for other animals? And is there data on what portion of people would substitute e.g. chickens or cows for bivalves but not also substitute chickens or cows for one of many plant options?

The claim you are making here is not backed by the linked source and appears to be directly contradicted by the linked source. The linked study appears to be referencing diets with "novel" plant-based ingredients (e.g. vegan junk food) in contrast to diets that use "traditional" plant-based ingredients (e.g. "pulses, legumes and vegetables") and the study directly states that "all diets with traditional plant-based substitutes met daily requirements for calcium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, iron and Vitamin B12 and were lower in saturated fat, sodium and sugar than the reference diet."

I don't feel as informed on this point, but I do think the human health risks associated with bivalve consumption were not given adequate consideration here, especially because some of the purported advantages pertain to survival scenarios. In addition to the heavy metal concerns, bivalves are also potentially one of the greatest sources of food poisoning, a concern that may be even more relevant in a catastrophe with increased environmental pollution and decreased access to both medical care and decontamination information. It seems unlikely that depuration will be carried out successfully in many of the places or times where failure will be the most harmful.

Other concerns:

Overall, I think this is a risky proposition and I worry about EAs getting excited about it based on weak assumptions.

Thanks so much for your response Rockwell, really appreciate it. The detailed inspection of the supporting evidence is really valuable for me, because it helps improve the quality of the thesis and so that we all have a more accurate understanding of the benefits and drawbacks. I’d also like to share my thoughts in more detail on some of the points you raised.

I believe that plants comprise the largest category of protein because they are much cheaper than meat or seafood. They are an inferior good in an economic sense, compared with meat as a normal good, and seafood as a luxury good. As incomes rise, people consume a higher proportion of meat. (This is also why asking people to substitute plants for meat generates resistance)

For a less technical viewpoint, evidence comes from a poll of people's food preferences of their most liked foods. Going through the list and excluding the items that don't contain significant amounts of protein, it looks like almost all of the most liked foods are entirely meat, or mostly meat. There are one or two exceptions such as Bibimbap or Fajitas, which have only a small amount of meat. Generally, plant foods are not the favorite foods unless they are made into sweet desserts.

It seems intuitively obvious to me that bivalves substitute for meat, since if you want to substitute for a normal good, you’d be willing to do so with a luxury good but not with an inferior good. But I don’t have a citation for that.

A blogpost about this says:

“A recent meta-analysis and systematic review reviewed the available research on this subject (both peer-reviewed and conducted by advocacy organizations to inform their decision-making). So what have we learned? Trying to convince people to eat less meat works—but with some very serious caveats.

Almost no one is turned off by being told about how bad eating meat is, and many people do decide they want to eat less meat. Some of those people actually eat less meat, while others don’t but rationalize that they ate less when filling out surveys. But it’s hard to stick to any major dietary change, and within a few weeks or months they’re off the wagon for good.

Ultimately, the solution is good meat substitutes that make it easy for people to become vegetarian.”

Plants are not a good meat substitute. Bivalves are a good meat substitute. If people think this is not completely obvious, and is something that needs additional evidence, I could pay for a Mechanical Turk survey. Maybe a question like “If you were to stop eating chicken/beef/pork, which would you prefer to substitute it with: vegetables or bivalves?”

I wrote that “Another potential substitute for meat is plant-based meat. Bivalves are far healthier than current plant-based meat alternatives, which have minimal health benefits”. The source refers to “novel plant-based ingredients”, which is their term for plant-based meat.

It’s possible that you thought I was comparing bivalves with traditional vegetarian/vegan diets? I’m not sure how to phrase it any clearer than what I wrote. If you have a suggestion for clearer phrasing to indicate that I am comparing bivalves to plant-based meat as potential substitutes for meat, and not to traditional vegetarian/vegan diets, that would be great.

I was initially upset because you accused me of quoting a source that directly contradicts my claim, but it looks like it was likely a misunderstanding. Please let me know if this is the case. Thank you!

Definitely - food poisoning is quite common with bivalves when they are eaten raw. For example, in the Western cultural context, oysters are typically eaten raw soon after being shucked. Parasites can easily enter the body this way.

In developing countries, this is less common because bivalves are generally eaten cooked. So for developing country consumption, I am more concerned with heavy metals. Assuming that bivalves substitute for meat/seafood consumption, they would have slightly more than meat, and much less than most seafood. So it would be a negligible harm compared to the benefits.

Regarding bivalve suffering - I am personally not as interested in this point because I see it as a type of "nirvana fallacy". For example, potential insect suffering is much more pertinent. There are 10 quintillion insects in the world, which is 8-9 orders of magnitude more than farmed bivalves. Insects also have an order of magnitude shorter lifespan than farmed bivalves. Insects are more sentient and experience more suffering than bivalves. They have a central nervous system and bivalves do not.

Any increase in bivalve suffering, multiplied by the very small chance that they suffer, multiplied by the small amount of suffering in the case they do suffer, means that it's not a material consideration. The entire suffering could be ameliorated by humanely destroying less than 1 hectare of termite nests, like “carbon credits” but for suffering. This is just my opinion of course, and different people will have different ethical weights.

I really want fish and bivalves to be a more prevalent and environmentally friendly option. I really appreciate you doing this write up and I expect to reference it in the future in conversation and when I have a question. Thank you so much for doing an exploration into this important and neglected topic!