This transcript of an EA Global talk, which CEA has lightly edited for clarity, is crossposted from effectivealtruism.org. You can also watch the talk on YouTube here.

Probabilistic thinking is only a few centuries old, we have very little understanding on how most of our actions affect the long-term future, and prominent members of the effective altruism community have changed their minds on crucial considerations before. These are just three of the reasons that Will Macaskill urges effective altruists to embrace uncertainty, and not become too attached to present views. This talk was the closing talk for Effective Altruism Global 2018: San Francisco.

The Talk

Thanks so much for an awesome conference. I think this may be my favorite EAG ever actually, and we have certain people to thank for that. So let's put a big round of applause for Katie, Amy, Julia, Barry, and Kerri did an awesome job. Thank you.

Now that I've been to the TED conference, I know that they have an army of 500 people running it, and we have five, which shows just how dedicated they are. But we also had an amazing team of volunteers, led by Tessa. So, a round of applause for their help as well. You all crushed it, so thank you.

Let's look at a few conference highlights. There was tons of good stuff at the conference, can't talk about it all, but there were many amazing talks. Sadly, every EAG, I end up going to about zero, but I heard they were really good. So, I hope you had a good time there. We had awesome VR.

I talked about, from animal equality, I talked about the importance of, or the idea of like really trying to get in touch with particular intuitions. So I hope many of you had a chance to experience that.

We also had loads of fun along the way. This photo makes us look like we had a kind of rave room going on. I want to throw particular attention to Igor's blank stare, but like a little smile. So you know, I want to know what he was having. And then, most importantly, we had great conversations.

So look at this photo. Look how nice Max and Becky look. Just like, you know, you want them to be your kids or something like it. It's kind of heartwarming.

My own personal highlight was getting to talk with Holden, but in particular him telling us about his love of stuffed animals. You might not know that from his Open Philanthropy posts, but he's going to write about it in the future.

I talked about like having a different kind of gestalt, a different worldview. The aspect of that, that feeling of gestalt shift, was actually most present for me in some stuff Holden said. In particular, he emphasized the importance of self care, this idea that he worked out what's the average number of hours he works in a week, and that's his fixed point, he can't work harder than that, really. And that there's no reason to feel bad about it. And yeah, in my own case, I was like, "Well obviously I kind of know that on an abstract level, or something." But hearing it from someone who I admire as much, and I know is as productive as Holden is, really helped turn that into something that I feel... now I think I am able to feel that on more of a gut level.

So, the theme of the conference was Stay Curious. And I talked earlier on about the contrast between Athens and Sparta. I think we definitely got a good demonstration that you are excellent Athenians, excellent philosophers. In particular, I told the story about philosophers at this old conference not being able to make it to the bar after the conference. Well, last night, attempting to go to the speakers' reception, two groups of us, one goes into an elevator before us, me and my group go in, go down, and the others just aren't there. Scott Garrabrant tells me they went from the fourth floor down to the first, doors opened, doors closed again, and they went right back up to the fourth. So, I don't want to say I told you so, but yeah, we're definitely doing well on the philosopher side of things.

So, we talked about being curious over the course of this conference. Now I'm going to talk a bit about taking that attitude and continuing it over to the following year. And I'm going to give quickly three arguments, or ways of thinking, just to emphasize how little we know, and how important it therefore is to keep such an open mind.

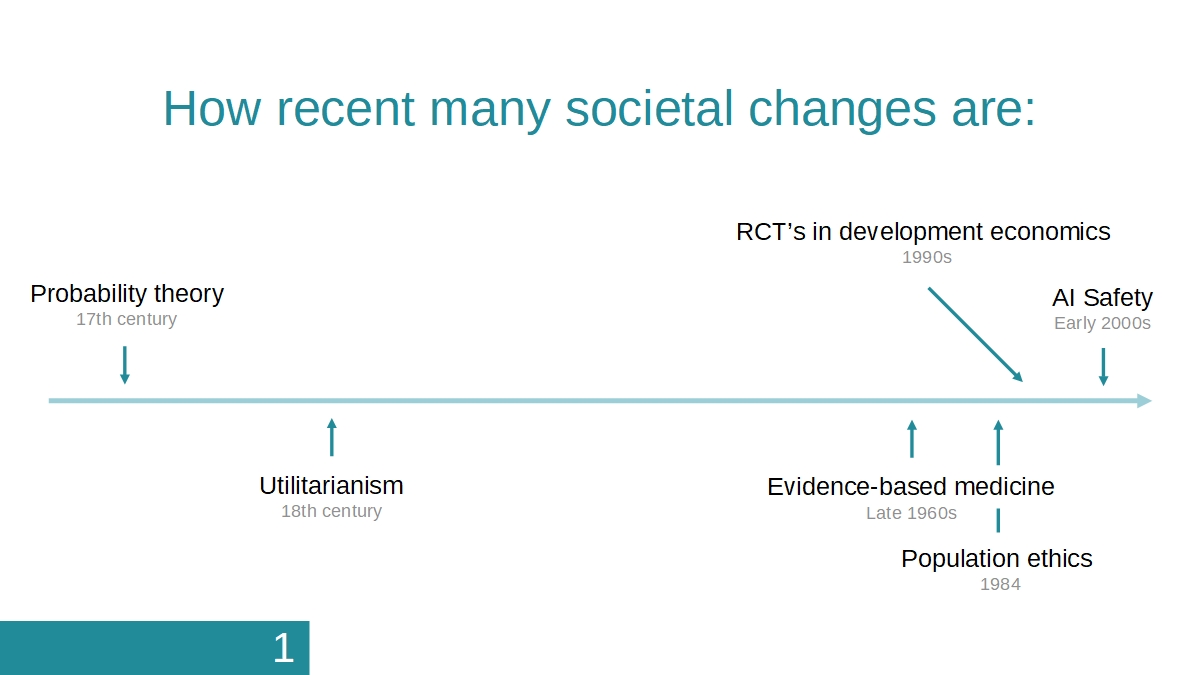

The first argument is just how recent many intellectual innovations were. The idea of probability theory is only a few centuries old. So for most of human civilization, we just didn't really have the concept of thinking probabilistically. So, if we'd made the argument like, "Oh, we're really concerned about risk of human extinctions, not that we think it's definitely going to happen, but there's some chance it'd be really bad." People would have said just, "I don't get it."

I can't even really imagine what it'd be like to just not have the concept of probability, but yet for thousands of years people were operating without that. Simple utilitarianism, again. I mean, this kind of goes back a little bit to the Mohists in early China, but at least in its modern form, it was only developed in the 18th century. And while effective altruism is definitely not utilitarianism, it's clearly part of a similar intellectual current. And the fact that this moral view that I think has one of the best shots of being the correct moral view was only developed a few centuries ago, well, who knows what the coming centuries have?

More recently as well, the idea of evidence-based medicine. The term evidence-based medicine only arose in the 90s. It actually only really started to be practiced in the late 1960s. There was almost no attempt to apply the experimental method more than 80 years ago. And again, this is just such an obvious part of our worldview. It's amazing that this didn't exist before that point. The whole field of population ethics, again, what we think of as among the most fundamental crucial considerations, only really came to be discussed with Parfit's Reasons and Persons, published in 1984. The use of randomized controlled trials in development economics, at least outside the area of health care, again, only in the 1990s, still very recent by societal terms.

And then the whole idea of AI safety, or the importance of ensuring that artificial intelligence doesn't have very bad consequences, again, really from the early 2000s. So this trend should really make us appreciate, there are so many developments that should cause radical worldview changes. I think it should definitely usher in the question of "Well, what are the further developments over the coming decades that might really switch our views again?"

The second argument is, more narrowly, really big updates that people in the EA community have made in the past. So again, with my conversation with Holden, he talked about how for very many years he did not take seriously the loopy ideas of effective altruism. But, as he's written about publicly, he's really massively changed his view on things like considerations of the long-term future, and the moral status of nonhuman animals as well. And again, these are huge, worldview-changing things.

In my own case as well, certainly when I started out with effective altruism, I really thought, there's a body of people who form the scientific establishment, and they work on stuff, and then they produce answers, and that's knowledge. Then, I thought you could just act on that, and that was the way the scientific establishment worked. Turns out things are a little bit more complicated than that, a little bit more human, and that just, unfortunately, the state of empirical science is a lot less robust than I thought. And that came out in the early days of relying on, say the Disease Control Priorities Project, which had much shakier methodology, and in fact mistakes that I really, really wouldn't have predicted at the time. And that's definitely been a big shift in my own way of understanding the world.

And then, in two different ways, from my colleagues at FHI, their views on nanotechnology. Where it really used to be the case that nanotechnology was... atomically precise manufacturing was regarded as one of the existential risks. And I think people just converged on thinking that actually that argument was very much overblown. On the other side, Eric Drexler spent most of his life saying like, "Actually, atomically precise manufacturing is the panacea. We can be at a post-scarcity world. We can have radical abundance. This is going to be amazing." And then was able to change his mind and actually think, "Well actually, I'm not sure if it's... it might be good, it might be bad. I'm not sure," despite having kind of worked and promoted these ideas for decades. This is actually kind of amazing, that people in the community are able to have shifts like that.

Then the third argument I'll give you, is that if we've made these updates, perhaps we will make such significant updates again in the future. So the third class of arguments is just all the categories of things that we still really don't understand. So, I mean, the thing I'm focused on most at the moment is trying to build this field of global priorities research to try and address some of these questions, get more smart people working on them. But one is just how we should weigh probabilities against very large amounts of value. So, we clearly think that most of the time something like expected utility theory gets the right answers. But then people get to start a bit antsy about it when it comes to very, very low probabilities of sufficiently large amounts of value.

When we then start thinking about, well, what about infinite amounts of value? If we're happy to think about very, very large amounts of value, as long-termists often are thinking about, if we think it's not wacky to talk about that, why not about infinite amounts? But then, you're really starting to throw a spanner in the works of any sort of reasonable decision theory.

And it just is the case, we just have like no idea at the moment really, how to handle this problem. Similarly with something Open Phil has worked a lot on: which entities are morally relevant? We're very positive about expanding the moral circle, but how far should that go? Nonhuman animals, of course. But what about insects? What about plants or something? Seems like we have a strong intuition that plants don't have consciousness, and perhaps they don't count. We don't really have any good underlying understanding of why that is the case. There's plenty of people trying to work on this on the cutting edge, like Qualia Research Institute, among others, but it's exceptionally difficult. And if we don't know that, then there's a ton we don't know about doing good.

Another category that we're ignorant about is indirect effects and moral cluelessness. So we know that like most of the impact of our actions are in unpredictable effects over the very, very long term, because of butterfly effects and so on, because of the ways that our actions will change who is born in the future. We know that that's actually where most of the action is, and it's just that we can't predict it at all. So we know we're just peering very dimly into the fog of the future. And there's been basically almost no work on really trying to model that, really trying to think, well, you take this sort of action in this country, how does that differ from this other sort of action in this other country, in terms of its very long-run effects?

So it's not just that we've got this general abstract argument, looking inductively from experience in terms of how we've, as a society and as a community, changed our mind in the past. It's also that we just know that there's tons of things that we don't understand. So I think what's appropriate is a attitude of deep, kind of radical uncertainty when we're trying our best to do good. But what kind of concrete implications does this have? Well, I think there's kind of three main things.

One is just actually trying to get more information, so continuing to do research, continuing to engage in intellectual inquiry. Second is to keep our options open as much as possible, ensuring that we're not closing doors, that even though they look not too promising, they might actually turn out to be much more promising than they were, when we gain more information going into the future, and when we change our minds. Thirdly is plausibly pursuing things that are convergently good. So things that look like, "Yeah, this is a really robustly good thing to do from a wide variety of perspectives or worldviews." So, reducing the chance of a great power war for example. Even if my empirical beliefs about the future changed a lot, even if my moral beliefs changed a lot, I'd still feel very confident that reducing the chance of major war in our lifetime would be a very good thing to do.

So, the thing I want to emphasize to you most is keeping this attitude of kind of uncertainty and exploration through what you're doing over the coming year. I've emphasized Athens in response to this Athens versus Sparta dilemma, trying to bear in mind that we want to stay uncertain. We want to keep conformity at the meta-level and cooperate and sympathize with people who have very different object-level beliefs to us. And so, above all, we want to keep exploring and stay curious.

"Where it really used to be the case that nanotechnology was... atomically precise manufacturing was regarded as one of the existential risks. And I think people just converged on thinking that actually that argument was very much overblown." - Why is it considered overblown?

This reminds me of a pretty excellent Simone de Beauvoir quote: "We must decide upon the opportuneness of an action and attempt to measure its effectiveness without knowing all the factors that are present." (From The Ethics of Ambiguity) I quite like this quote, because I don't interpret it as an argument against trying to measure and predict the consequences of an action, but rather, as an expression of the fact that uncertainty and incomplete information is a fact of life, and we must at some point act anyway rather than becoming paralysed by this. We should always be at least passively open to the possibility of new and unknown factors, and compassionate toward people (including our past selves) who have made mistakes or held views that turned out to be incorrect.