By Johannes Ackva

These posts were originally written for the Founders Pledge Blog so the style is a bit different (e.g. less technical, less hedging language) than for typical EA Forum posts. We add some light edits in [brackets] specifically for the Forum version and include a Forum-specific summary. The original version of this post can be found here.

Contextualization and summary

In the wake of massive climate policy wins in the US, it is prudent to ask how this step change in US climate effort changes the philanthropy landscape for impact-oriented donors. Framed in EA terms, a key question is how a much improved and enlarged policy effort affects marginal returns to advocacy, in particular how reasons to expect declining marginal returns (less neglectedness, overall a better effort with less room for improvement) and reasons to expect increased marginal returns (a much larger effort overall that can be affected and a reduced risk of failure of innovations failing in “valleys of death”) trade-off against each other.

While this will be the subject of future posts in this series, the present post focuses on setting the scene, recapitulating what happened, and establishing a perspective for how to evaluate different components of the recent wins and philanthropic attempts to improve their implementation – in particular arguing that there is very likely a negative correlation between what will reduce emissions in the US in the short-term (scaling mature technologies) and what is most significant about those bills in general (accelerating less mature technologies) – something that should affect our philanthropic foci.

Introduction

With the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act (together thoroughly reshaping and upgrading the US energy innovation system), as well as the midterm elections behind us, it is worth asking how the US climate action and philanthropy space has changed.

And, critically, how should our climate giving and grantmaking change in light of these developments?

We explore this question, drawing on our prior work on innovation advocacy and the impact of political developments, and try to incorporate a variety of developments to form a view on how innovation advocacy now compares to other opportunities, such as engaging with innovation work outside the US and/or via other theories of change.

To start, though, we will ask a much more narrow question: what happened and how can we make sense of it from a global perspective?

I. Background: 2021-22 - A period of massive climate wins

As we hopefully predicted in our 2020 report on the implications of Biden’s win for climate philanthropy, the last two years have seen dramatic progress in US climate policy with three major pieces of legislation having passed:

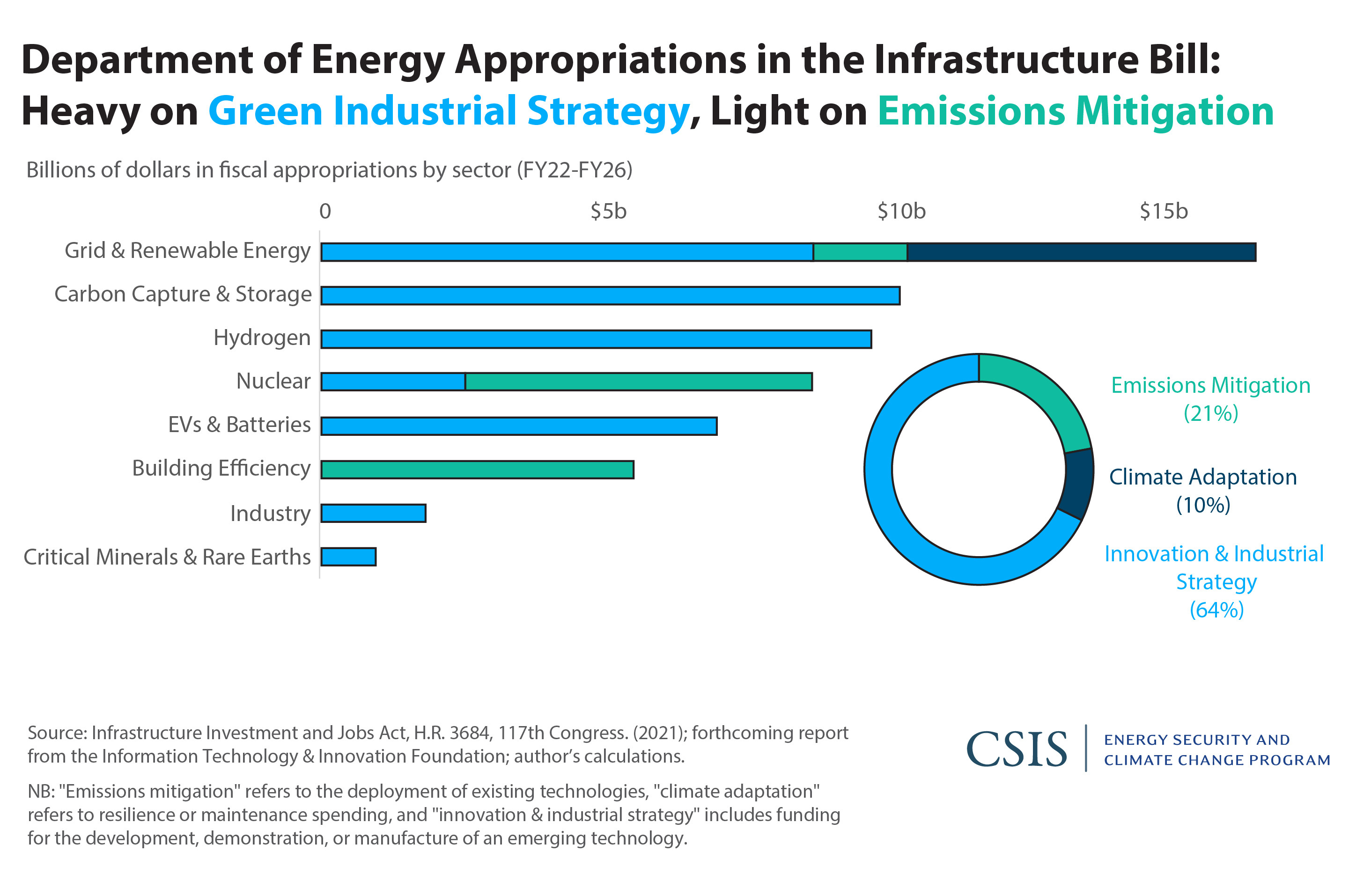

- Bipartisan Infrastructure and Investment and Job Act (IIJA) (2021): a bipartisan bill including investments in clean energy infrastructure as well as a large expansion of the US energy innovation effort, with – particularly noteworthy – increased attention on demonstration projects, a priorly missing link in the US innovation system. Most of the emissions effects here are over the long-term, with a meager 1% difference in emissions by 2035 compared to business as usual (according to REPEAT project’s modeling), but there are many innovation bets that could have large effects globally. An analysis by CSIS illustrates the focus on innovation (blue, below) compared to short-term emissions mitigation (green), arguing that the IIJA will do more to achieve 2050 than 2030 emissions targets:

- CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS) (2022): a bill increasing the overall innovation effort in the United States, with some climate-specific provisions. As with the IIJA, the main focus is on innovation and long-run changes to US innovation and competitiveness;

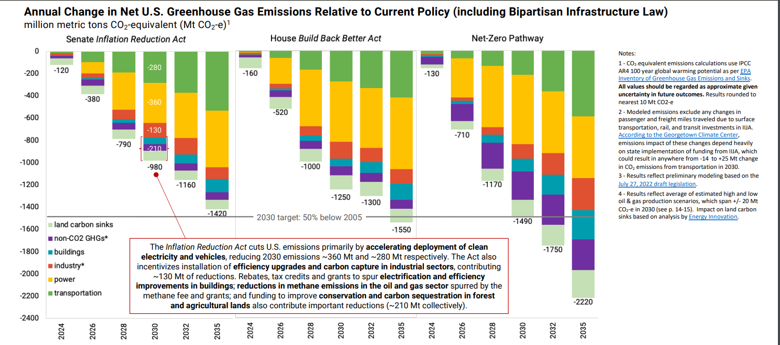

- The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) (2022): more than USD $360 billion of comprehensive investment into US decarbonization through tax credits, loans, and other “carrots” to accelerate the adoption of clean alternatives throughout the economy; a bill with tangible effects on US emissions over the next decade, shifting US emissions about 15% lower by 2035 than they would otherwise have been, according to the REPEAT project’s modeling.

The sum here is more than its parts.

As Nicholas Montoni puts it in an analysis of the interplay of the three bills: “The bigger picture here is that each of these clean energy bills supports a particular aspect of our clean energy innovation continuum: basic science and discovery (CHIPS), scale-up of emerging technologies (IIJA), and deployment, deployment, deployment (IRA)."

Together, they constitute a trajectory-changing moment for US climate policy, reshaping the outlook on US emissions as well as clean energy progress.

For anyone who wants to dive deeper, American climate journalist David Roberts’ podcast series on the Inflation Reduction Act is excellent listening, while the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) provides a thorough analysis of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill (here and here), and this joint piece by various organizations provides a great introduction to the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), one of the most exciting institutional innovations of recent bills.

II. The global significance of US climate wins

While a lot of the discussion, in particular around the IRA, has focused on how much closer these developments will put the US towards its 2030 target, the real significance of the IRA and the other bills lies in their global effect over this century – with total cumulative US emissions reductions until 2032 (over 10 years for a total of 6.3 gigatons (GT)) in the order of 12% of current annual global emissions (around 50 GT). Put differently, this means that, despite its tremendous significance for US climate policy, the IRA and other climate policies will shave off just more than 1% of global emissions directly over this decade per year.

Luckily, there are at least two powerful mechanisms for these pieces of legislation to have much wider global effects – policy leadership and innovation.

Before we dive in, a brief note on methodology. Throughout the course of the following exploration, we will often use rough “back-of-the-envelope” estimates that are certainly wrong and imprecise. The reason for this lies in the nature of what we are talking about, namely, indirect uncertain effects through space and time. While it might seem objectionable to put rough numbers – guesstimates – on these effects, we think it is important to do so because the alternative, just mentioning those effects as an afterthought or a qualitative consideration, effectively sets those effects to zero even though they might be the most important ones. Treating effects as zero just because they are uncertain or evolve over time is likely more misleading than approximating effects with rough estimates (see also here for a related argument as to why we should not just ignore uncertain effects).

Policy leadership

While the recent COP27 conference has been a disappointment in not achieving commitments for more ambitious global emissions cuts, it appears likely that the strengthened US climate policy effort will help achieve more ambitious targets in the future, compared to a counterfactual scenario without passage of the IRA. It also seems likely that, had the US not passed the IRA, the risk of backsliding on global targets would have been even larger.

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to say anything specific about these effects, but the basic emissions math – any one country being small in terms of global future emissions – and the expected leadership role of the US, suggests that the effect is large. Even if the existence of a strong US climate policy framework (the IRA) only reduced global emissions outside the US by 1% through its effect on inspiring action and avoiding backsliding, this effect alone would almost double the IRA’s effectiveness (increase it by 70%).[1]

Innovation

As we have seen in the discussion above, two of the three most significant climate bills of the Biden agenda – the IIJA and CHIPS – are explicitly focused on innovation, seeking to achieve progress on climate through changing the technological trajectory.

But even for the least innovation-focused of these bills, the IRA, the main effect on global emissions will likely be induced technological change over time, rather than short-term reductions in US emissions.

Green hydrogen example

To understand this, consider the example of clean/green[2] hydrogen -- a key lever to decarbonize sectors where direct electrification is challenging.

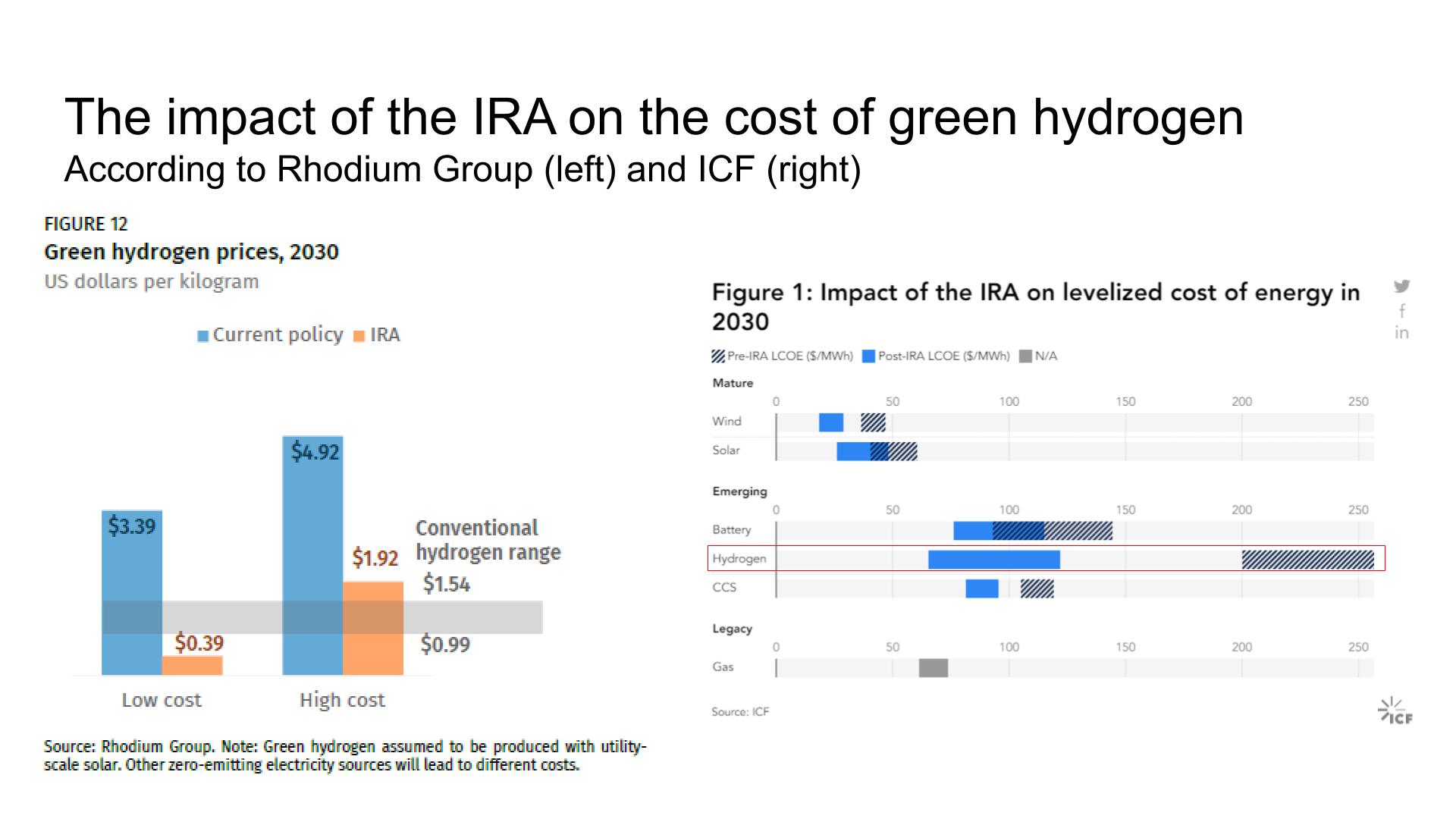

In ICF’s modeling of the IRA, clean hydrogen achieves the largest cost-reduction across all modeled technologies, suggesting a 60% reduction in cost, compared to the counterfactual of no IRA. Rhodium Group’s analysis independently models cost-reductions for green hydrogen at 60-90% cost-reduction through the IRA by 2030. Crucially, Rhodium Group’s analysis also suggests that this would lead green hydrogen towards being cheaper than high-carbon alternatives by 2030 in the optimistic case (low-cost assumptions) and close to cost-competitiveness in the pessimistic case (a high-cost scenario):

A conservative back-of-the-envelope calculation -- assuming that this acceleration of trajectory in green hydrogen, with cost reductions of 60-90% by 2030 (!), would only lead to a three-year acceleration of achieving a 5% abatement of global emissions through green hydrogen -- would suggest an emissions reduction of 4.5 GT from the green hydrogen component of the IRA alone. So, even under these conservative assumptions, the innovation effect of trajectory change in a single technological pillar would be close to the total estimated emissions effect of the IRA in the US over the next decade (6.3 GT).

Meanwhile, of the estimated 6.3 GT in total emissions reductions in the US over the next decade (by 2032, i.e. two years beyond the 2030 target, according to REPEAT Project 2022, p. 6), about ⅔ will be in the power and transport sector, primarily through the deployment of renewables and electric cars -- technologies where the innovation effects of additional deployment will be considerably lower than for less mature technologies.[3]

For example, even though the IRA is expected to lead to a massive increase in solar capacity additions -- a 5x increase in solar capacity additions by 2025 compared to 2020 (REPEAT Project 2022, p. 11) -- additional levelized cost reductions in solar through the IRA are only estimated to be in the 30% range compared to a 60% reduction for green hydrogen (ICF). [4]

Furthermore, these cost reductions are less relevant than for other technologies given both that solar is already competitive on the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) in many locations and that the key constraint is not levelized cost, but rather availability, siting, transport and storage infrastructure.

III. What this means for climate activists and philanthropists

We are thus in a situation where the following is likely to be true:

Thinking long-term and globally changes what is most important

- (1) US short-term reductions are dominated by mature technologies: The most significant short-term emissions reductions from the Biden policy window in the US which we can predict will be through the increased deployment of mature technologies, such as solar, wind and electric cars;

- (2) However, the main effects of Biden climate policies will be on other technologies that have not yet reached maturity: Even under quite conservative assumptions, the main effect of Biden’s climate policies on emissions reductions will “travel through” cost reductions and other improvements of currently immature technologies. This seems already true for the IRA and will be even truer once we take into account the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 and the IIJA, which do not even (seriously) aim to reduce emissions in the US in the short-term, but rather focus on improving the US energy innovation pipeline, i.e. prioritizing long-term global effects;

- (3) There is, thus, a negative correlation between short-term emissions reductions in the US by 2030 and the global significance of components of the IRA, IIJA and CHIPS Act: By and large, the policy components driving most of the emissions reductions in the US until 2030 are those where innovation effects are relatively lower, whereas the more globally relevant changes will reduce less emissions in the US by 2030. If a technology can reduce significant emissions in the US by 2030, then it is probably already (close to) mature. This, however, means that the technological learning per additional capacity is limited, as the steepest cost reductions usually appear in early deployment.

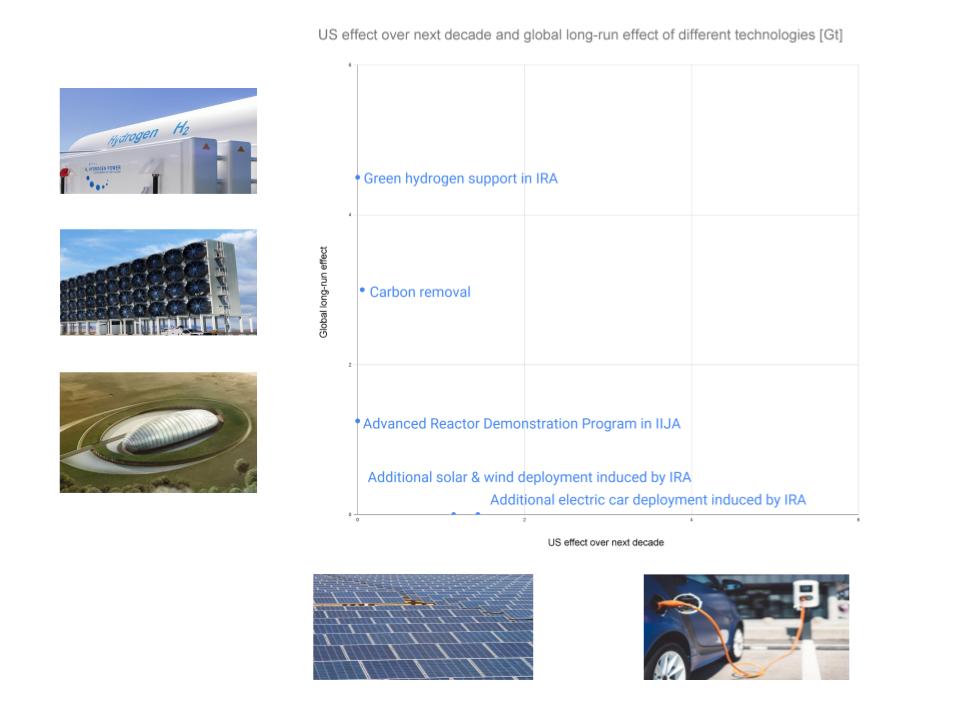

A visualization

To see this more clearly, consider the following visualization which tries to make reasonable estimates (data and some reasoning here) on the relative value of different parts of the legislations on US emissions until 2032 (using published estimates where available) and on the long-run global consequences. Note that this is about additional emissions savings through the legislation, not the total potential of those technologies, and that the estimates about innovation effects are intentionally conservative to bias against the argument we are making.

While those estimates are, of course, highly uncertain, and we hope to refine and expand on them in the future, here they are really just meant to more clearly make an important point that should be uncontroversial, but is – we believe – underappreciated: given that US emissions until 2032 are a small part of future emissions, but that the US is a major energy innovator – and much more so with the recent policy wins – we should appreciate the significant leverage that comes from helping make sure as many of those innovation bets as possible are successfully realized.

[As discussed, the back-of-the-envelope calculations here are very rough and we are keen to do more BOTECs on this in the future, also curious for ideas in the comments.

However, the basic point, that indirect innovation and technological learning effects will dominate the domestic impacts of US climate policy, and that this will be more so for less mature technologies, seems very robustly true to us from a variety of angles discussed throughout the post, e.g. the BOTECs, modeling on cost reductions, and the generalized lesson that earlier technology support reaps larger benefits while being comparatively more additional by default.]

What to look for when evaluating success

If 1 to 3 above are true, this has a couple of surprising implications for how to evaluate the implementation of Biden’s climate bills:

- (4) Modeled or observed emissions reductions patterns in the US by 2030 are not a good proxy for the significance of policy components: This is the case since those patterns will primarily be driven by already mature technologies that represent a minority of the global impact of the Biden climate bills;

- (5) Other signals are at least similarly important to look out for when evaluating the success of policies going into implementation: E.g. “What are the cost trends we can observe for technologies not quite mature enough to drive significant emissions reductions, such as green hydrogen or carbon capture and storage?”, or: “Is the strengthened framework for energy innovation established by the Energy Act of 2020, IIJA, and CHIPS and Science Act funded sufficiently and does it operate well?”, “Is the new Office on Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) succeeding?”, Or: “Are the bets around advanced nuclear and geothermal paying off?”

While it is unlikely that these ways of tracking progress will be entirely disjointed – after all, both stronger local action and stronger innovation policy become more likely with stronger overall support for climate policy – they are far from perfectly correlated. At the very least, this makes it important to look at “other signals” carefully in addition to emissions reductions.

Implications for action

However, the most important implication for action comes from comparing estimated importance to estimated existing attention and tractability.

Firstly, because activism, existing clean energy interests, and the overall mainstream climate discourse are heavily focused on short-term local or national targets as well as deploying mature technologies, impact-oriented philanthropists seeking to improve the trajectory of less mature technologies have the benefit of acting in a less crowded space where additional funding can make a larger difference.

Importantly, because policy support at early stages is often less politicized as it requires fewer jurisdiction-level regulations and controversial siting decisions, there is also an argument that one should expect improving earlier-stage support to be more tractable philanthropically, e.g. by funding the research and engagement of new offices, such as the OCED, maximizing the positive effect of the improved institutional and funding environment.

Thus, for impact-oriented philanthropists, at least tentatively, three independent factors speak in favor of primarily focusing on strategies improving the parts of the IIJA, IRA and CHIPS implementation that affect less mature technologies: (i) larger actual relevance (higher importance) as well as (ii) lower crowdedness (higher additionality) and (iii) lower politicization (suggesting higher tractability). They thus do well on metrics usually considered important in philanthropic effectiveness.

One should not take this view to the extreme and be entirely “surgical” –– all climate policies profit from a policy and regulatory environment where it is easier to build things, and where the overall support for climate policy is higher. And, indeed, this is very much a marginal argument given what everyone else is doing (i.e. not everyone should change tack!).

But in a situation where the implementation of the IIJA, CHIPS, and IRA, as well as the push for new additional climate policies, will lead to a continually crowded advocacy space, it is worth remembering that some projects, policies, and budgetary choices are much more important than others and, crucially, that our discourse’s focus on short-term local emissions reductions will often lead us astray as to what those important actions are. When trying to have the most positive impact on shaping the climate trajectory, a clear-eyed view of the global ramifications of different local actions is crucial, and something we will continue to work on and talk about in more detail going forward.

About Founders Pledge

Founders Pledge is a community of over 1,700 tech entrepreneurs finding and funding solutions to the world’s most pressing problems. Through cutting-edge research, world-class advice, and end-to-end giving infrastructure, we empower members to maximize their philanthropic impact by pledging a meaningful portion of their proceeds to charitable causes. Since 2015, our members have pledged over $7 billion and donated more than $700 million globally. As a non-profit, we are grateful to be community supported. Together, we are committed to doing immense good. founderspledge.com

- ^

Back of the envelope estimate: global emissions are around 50 GT/year, US is around 5-6, so 44 GT outside US, of which 1% would be 0.44 GT/year compared to the estimated annualized effect of the IRA of 0.63 GT/year.

- ^

The examples here are drawn from green hydrogen, hydrogen produced with renewable electricity, though Rhodium uses a broader terminology (“clean hydrogen”) which also includes other zero-carbon ways to produce hydrogen.

- ^

In learning curve models that are canonically used to describe the relationship between cumulative deployment and cost, cost reductions are expressed as a rate per cumulative capacity doubling, implying a lower marginal cost-reduction effect with a technology having been deployed more. Of course, this effect – the relative primacy of early effort – becomes even more pronounced when taking into account innovation activity before first deployment.

- ^

This is not a perfectly independent comparison, as solar electricity might be used to power electrolyzers for hydrogen production (i.e. cost reduction in solar is a component of green hydrogen cost). Note, however, that this makes the principal conclusion stronger as it implies that the cost-reductions in the non-electricity components of green hydrogen production must be significantly larger to reach the aggregate total of 60% cost reductions for green hydrogen overall.