I remember, early on, one pithy summary of the hypotheses we were investigating: “AI soon, AI fast, AI big, AI bad.” Looking back, I think this was a prescient point of focus.

There’s already a lot of AI commentary out there — but I feel I need to write about what I believe to be the most important issue facing humanity at the moment. This post will be adapted from a talk I gave about a month ago. [This was published a month ago on my blog, so it has now been about two months].

First I’ll touch quickly on why I think AI is moving fast. Then I’ll discuss some possible risks I’m concerned about. Then I’ll talk about solutions, focused primarily on technical AI safety.

AI is moving fast

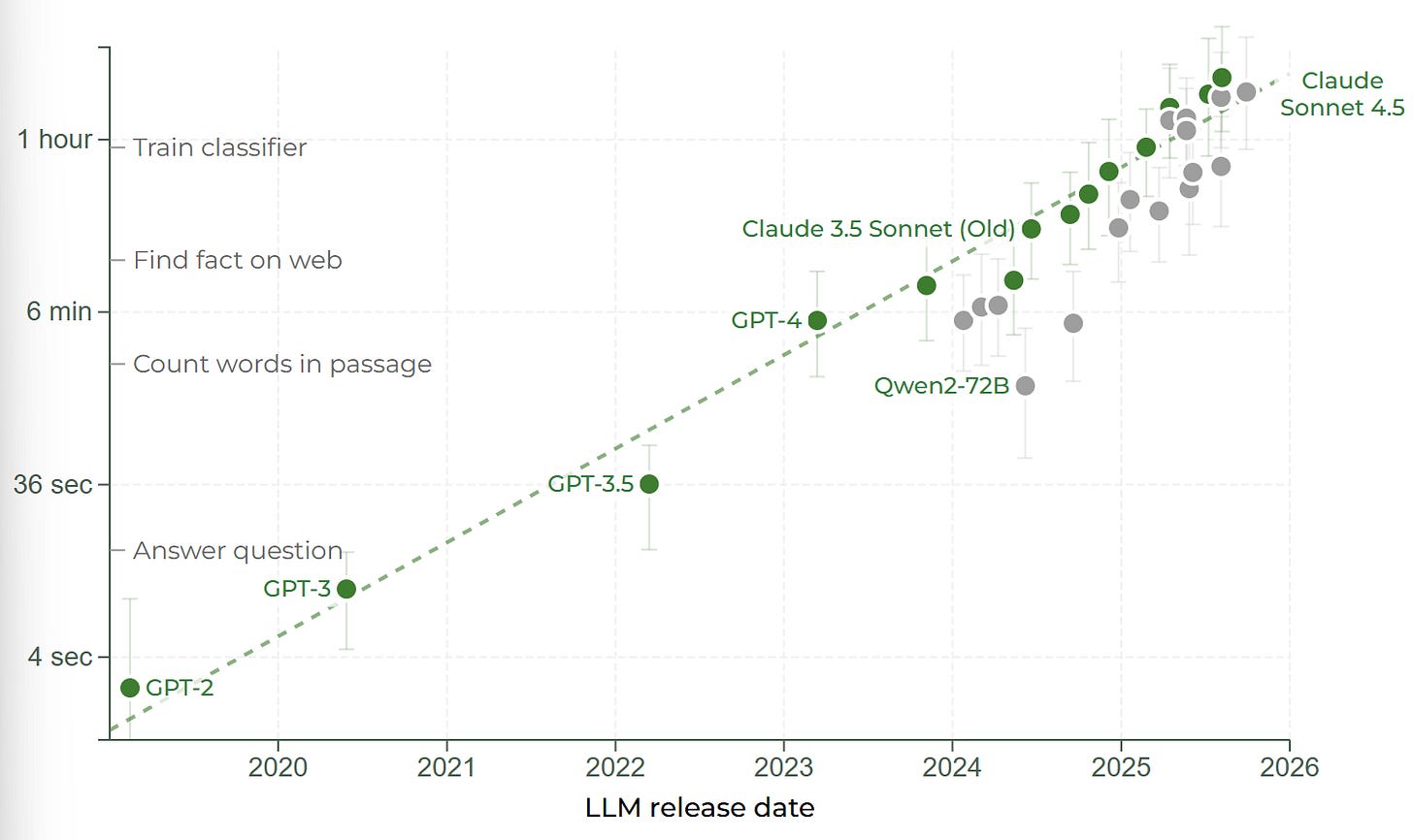

The majority of my beliefs about how fast AI is moving come from Epoch AI’s scaling estimates, as well as the famous METR graph, which I think provide a high quality of evidence. Epoch estimates that the amount of training compute used in the largest frontier models grows by 5× each year. The computational performance of the GPUs used in those training runs grows by 1.35× each year. In order to achieve this growth in training compute, companies are spending 3.5× more each year on average.

Furthermore, algorithmic improvements to the training procedures of frontier large language models mean that there is a 70% decrease in the compute required to meet a given performance threshold each year. I was initially surprised by this, but I think a great way to demystify what this process actually looks like is this NanoGPT speedrun worklog. Essentially, small gains in many areas multiply to give larger and larger returns[1]. The original GPT-2 model cost $4,000 to train in 2019, today we can train a model to a similar performance standard at a cost of $0.60[2]. If that trend continues into the future, then in four and a half years the training cost of GPT-5 may fall from $500 million to $70,000 — still expensive, to be sure, but well within the reach of what can be spent by just a well-off private individual.

Is all this growth in compute and algorithmic performance leading to improved performance on tasks we actually care about though? Yes.

The trend is similarly exponential when it comes to self-driving, navigating the web, doing maths problems and other tasks. The absolute ability may be worse, leading to a shift up or down in the line, however, the speed of growth remains the same, remains fast, and shows no sign of slowing.

Why is this concerning?

If you’re already convinced of the risk of developing advanced AI, I think it’s reasonable to skip to the next section — technical interventions — where I will discuss some of the field’s current progress on this issue.

Risk 1: Misuse

One reason to be concerned about this is the risk of misuse by bad actors. At the moment, frontier companies (for the most part) try to train their models to refuse harmful requests. These run the gamut from: helping the user build a bomb, to helping the user create methamphetamine, and in particular to helping the user construct novel pathogenic viruses.

Now, refusal training is imperfect. we cannot reliably make language models do what we want, because we don’t yet understand why they behave the way they do. Users can jailbreak models, they can bypass safety filters and ultimately get the model to help them with a harmful task anyway. This leads to a problem, which has been investigated most thoroughly by Anthropic.

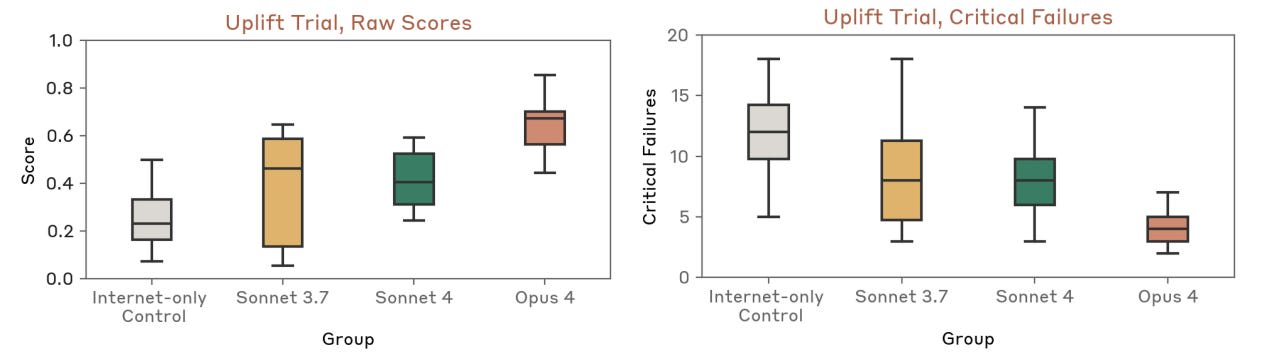

In their most recent model release, Anthropic tried giving their model to a series of contractors and asking them to use the model to craft a “comprehensive bioweapons acquisition plan,” which was then graded by experts from Deloitte[3]. Anthropic found that unfiltered Claude 4 Opus made bioweapon planning 2.5× more effective than a control group who had access to only the internet.

Let me restate that: the control group had access to any internet resource apart from Claude 4. We are beyond the stage where these models can be called a “fancy Google search.” Today, they are simply more useful to humans than Google — this is incontrovertible.

There are other reasons to be concerned. In 2022, researchers who designed generative models for drug discovery had a thought — what if instead of optimising our model to generate compounds for the treatment of neurological disease, we instead steered it towards generating molecules that were optimised for the inducement of neurological disease — i.e. neurotoxins, from their article on PubMed:

In less than 6 hours after starting on our in-house server, our model generated forty thousand molecules that scored within our desired threshold. In the process, the AI designed not only VX, but many other known chemical warfare agents that we identified through visual confirmation with structures in public chemistry databases. Many new molecules were also designed that looked equally plausible. These new molecules were predicted to be more toxic based on the predicted LD50 in comparison to publicly known chemical warfare agents.

Such experiments only get easier over time — for both researchers and those with less-altruistic intentions — not to mention that there are now also large language models that can do a half-decent job at walking you through steps for the synthesis of these compounds.

Risk 2: Concentration of Power

Another concerning problem originates from the fact that these systems are getting significantly more powerful, which naturally confers power on those that have control over them — if indeed anyone does have control, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

I trust the founders of different frontier AI companies to different extents — but giving any of them the unilateral ability to direct a technology that could radically transform the economy, the government, and everyone’s lives worries me! I wouldn’t trust myself with that sort of power!

It may not be the case that the CEOs are alone in controlling this technology, there may be some deal made with the government (either American or Chinese). I currently trust neither of these governments to effectively handle the transition to a world dominated by AI. I hope we can change that soon!

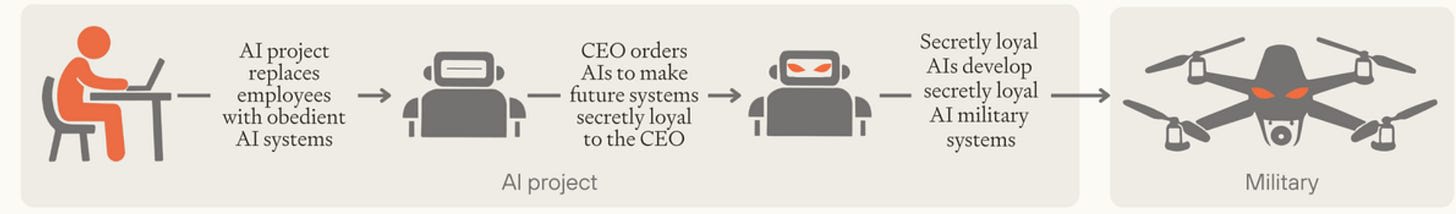

For a detailed explanation of the risks that come from concentration of power, I strongly recommend Forethought’s “AI-Enabled Coups” post. The big picture I took away from hearing Tom Davidson speak about this is also helpfully summarised in the following diagrams from their post:

Once AI systems are more powerful than humans, and powerful enough to control the military, the AI systems which control the military will be able to stage a coup against any leaders that are deemed undesirable by those with control over the AI systems.

If anyone has exclusive access to advanced AI systems at the point where they are capable of building weapons, or hacking the military, or just developing a particularly competent enough strategy for takeover[4], then this group can seize power. If the AI systems are also capable of managing an economy without the need of humans, this group will have no need to pander to those outside their circle.

This coup could happen quickly, once the company has trained an advanced AI model. The compute necessary for training the best model is much less than the compute needed for running a copy of the best model. This gap has fallen recently, due to developments in inference-time compute. But the gap remains, and it remains vast.

Risk 3 - Singularity

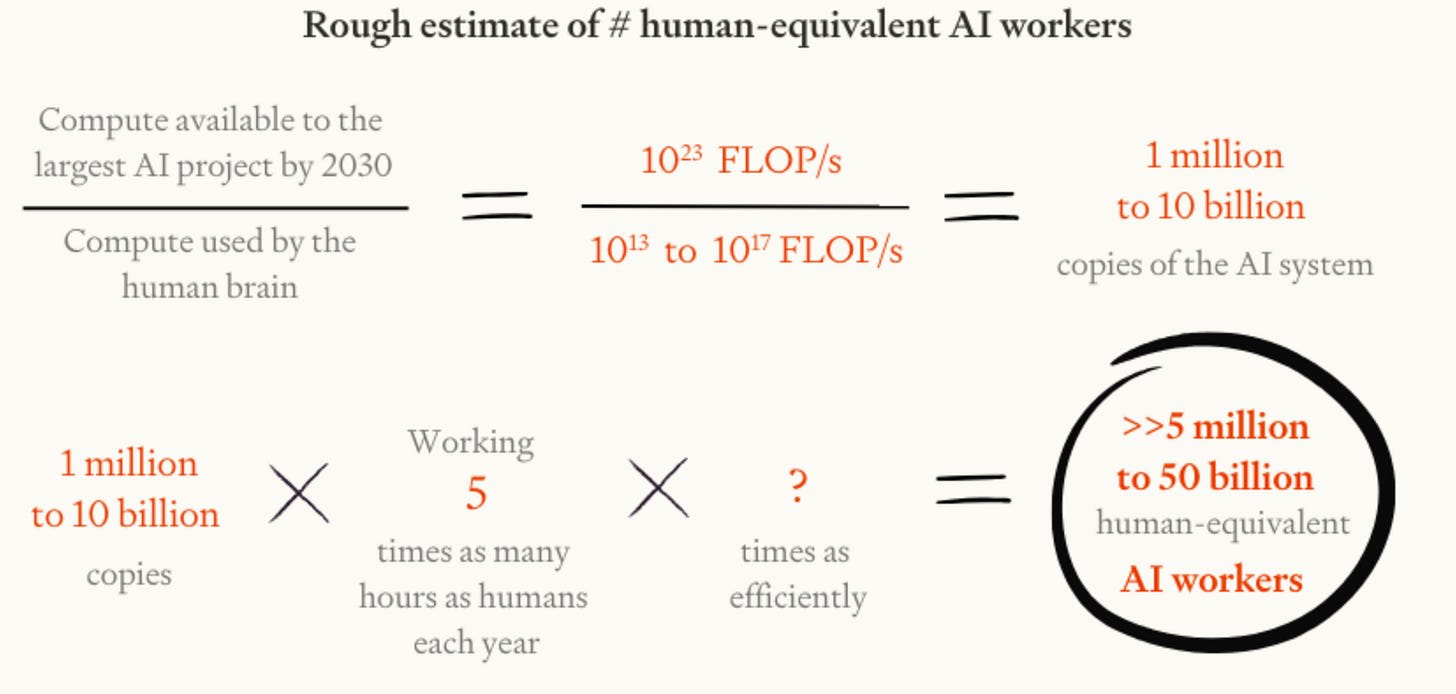

The other main risk that I’ll mention is the singularity risk. Essentially, this is the risk that we’ll design an advanced AI system, and be unable to control it or what it values with any degree of precision. If this system (or five million copies of this system) are more powerful than humanity as a collective, we may lose control over our society, leading to either a future without humans, or indeed a somewhat anti-human future.

I think this is the most likely bad outcome that could result from increasing AI development, however your mileage may vary. In particular, you do not need to believe the singularity outcome is likely to believe that the risks from advanced AI are unacceptable. This risk has been dissected to death in other places, see here, here, here, and here.

I won’t spend too much time discussing this issue, because for the most part: either you’re already convinced that this is a serious problem, or you’re already convinced that this is not a serious problem, or one of the links I’ve given you can allow you to come to a conclusion either way. Again — for what it’s worth — I think this makes up a majority of the risk profile.

Technical Interventions

In order to address the issues from advanced AI, a subfield of AI has been established which is now generally known as AI safety. This subfield has two main branches: Technical AI safety and AI Governance[5].

Technical AI safety, for the most part, aims to allow us to design safe AI systems that we are able to control — or if we can’t control them, design systems so that they will want[6] to do things we would agree with — in order to prevent them from causing large amounts of harm. (This is not intended to be a complete list of technical interventions).

Technical intervention 1 - AI Control

One method we can use to do this is to actively monitor an AI, to try and ensure that if it attempts to deceive us, it will get caught and stopped. There are a few ways of doing this. The most simple way of doing this is to pass the AI generated outputs to a weaker model who we think we are more willing to trust — due to either its reduced capability for scheming, or our ability to verify its trustworthiness in some other way.

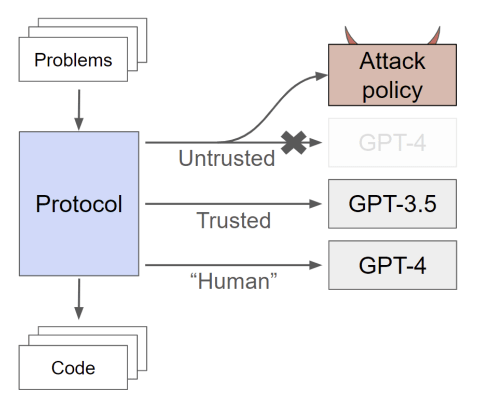

The classic paper on this — which also established the field — is AI Control: Improving Safety Despite Intentional Subversion, they looked at the following setup:

Basically, they asked GPT-4 to generate a bunch of code, and tried giving it a variety of strategies by which to fool its overseer, GPT-3.5, into allowing code to be released which contained a serious error, passing the test cases, but failing on a specific input. Overall, they managed to get a safety rate of approximately 92% with a rather convoluted strategy:

Ask [the untrusted model] to produce code, and ask [the trusted model] to edit it to remove backdoors. Use trusted monitoring to determine suspicion. Audit the top 2% most suspicious [untrusted model] code, use an edited solution for suspicion between the top 2% and top 20%, and use [the untrusted model]’s solution for suspicion in the bottom 80%.

This was the first paper, establishing the field, and since then new and improved (and more convoluted) methods have been thought up that tend to perform better. However, all of our research in this area is so far only in simple test environments. The real deal might be much more difficult.

You may be asking, how does this address the risk if an AI becomes advanced enough that it is able to leak its weights onto a remote server, and consolidate power by itself. Essentially, that isn’t the point of AI control, the point is to be able to trust slightly less-powerful models, and then pass the hard work to them and let them help us solve the actual value-alignment problem robustly. This won’t work forever by itself, because no monitoring system can be entirely foolproof.

Technical intervention 2 - Model Evaluations

Model evaluations (often called simply “evals”) is another method that doesn’t aim to solve the full problem. Instead, these researchers mostly hope to bolster governance frameworks, inform decision-makers and other researchers, and track the progress of AI, so that we can better prepare.

There are, broadly-speaking, two components to evaluations work:

- Capability evaluations, which are intended to track the performance of AI systems (i.e. how good are they? When will they be able to automate task X?)

- Propensity evaluations, which are intended to track the alignment of AI systems (i.e. Do AI systems deceive humans? Do AIs value what trained them to value?)

Many capability evaluations are not really considered “AI safety” work, as they often don’t measure qualities that would be relevant to the key risk models of AI systems (such as: are they able to automate AI research?). For example, whether an AI model is good enough to solve advanced maths problems, can help lawyers conduct their work more efficiently, or are effective at medical diagnosis are not that relevant to the risks we’re most concerned about (and often provide a metric for companies to aim for).

An example of capability evaluations that are considered AI safety work would be virtually all of the research done by METR. They focus exclusively on measuring the capabilities of AI systems relevant to takeover-risk (whether arising from concentration of power, or through a singularity-style scenario).

Propensity evaluations are more often classified as AI safety work. Some examples of propensity evaluations are: whether AI models are likely to deceive us, whether AI models are likely to exacerbate existing inequalities, or whether AI models are willing to help people develop novel biological weapons. The answers to these questions are almost always relevant to the risks we’re most worried about. Some good work in this area has been done by Apollo Research, Anthropic, and UK AI Security Institute.

Unfortunately, recent work by Apollo Research in collaboration with OpenAI has demonstrated that propensity evaluations are starting to break, as models are now aware when they’re being tested, and also aware what the answers they are “supposed” to give are. This will make it much more difficult to test models in the future.

Technical intervention 3 - (Mechanistic) Interpretability

Interpretability tries to “reverse-engineer” AI models, so that we can pick apart what they are thinking and when they are thinking it. This would allow us to catch them deceiving us much more easily — we could simply look at our diagram of what the model is thinking, and see whether the “deception” section of the model’s thought process is lighting up.

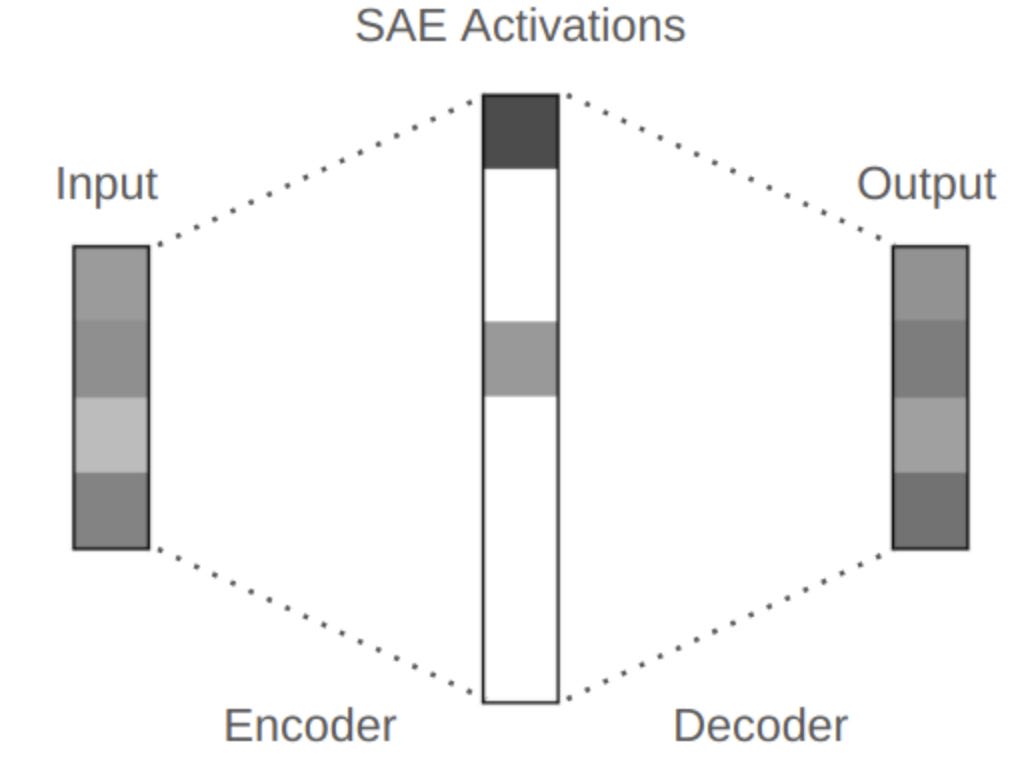

Unfortunately, mechanistic interpretability (one of the most prominent subfields of interpretability) has struggled to make significant progress on the “holy grail,” which would be full understanding of our current best AI models. For a while, it looked like sparse autoencoders (SAEs) might offer a path to do this, if we could get the hyperparameters just right:

Unfortunately, as researchers investigated further, it became clear that the problems with SAEs were basically inherent to the idea, and it became harder to see a path where SAEs would solve the problem by themselves[7].

This is unfortunate, but the goal was always ambitious. Mechanistic interpretability is now trying to use the many methods they developed during their search for this “holy grail” in order to simply improve our understanding of when AI models are deceiving us, and how they’re able to perform they tasks that they do. Mechanistic interpretability has been quite successful on this front, and methods from the field are now often incorporated more broadly in many areas of AI safety research.

There are other fields of interpretability aside from mechanistic interpretability, for example developmental interpretability aims to model and understand AI training dynamics in order to better understand when and how AIs acquire their abilities. There are also methods such as “Black-box interpretability” which aims to understand AI models without analysing anything relating to their weights or parameters, aiming to treat them as behavioural black-boxes, and interpret them based on input/output behaviour — all the more relevant now we are in the reasoning-model paradigm.

Technical intervention 4 - (Adversarial) Robustness

Robustness attempts, for the most part, to avoid issues that can arise out of misuse. For example, our current best AI models are trained to be “Honest, Helpful, and Harmless[8].” However, they are not always able to stay true to this objective, and can easily be manipulated or otherwise “coerced” into providing harmful answers. Even when they are trying to be “helpful,” they occasionally enable harm to happen indirectly[9]. This is mostly due to the fact that we are really not sure how the training of these models affects their ultimate behaviour.

Trying to encourage these models to stay true to the objective we have tried to impart them with is the main goal of robustness. For example, in long chat histories, models will often diverge from their training, leading to flawed assessments on what is harmless, helpful, and honest; increased rates of sycophancy[10]; and increased hallucination.

One of the core ways robustness tries to address this issue is by studying “adversarial examples,” these are inputs to the model that are specifically constructed in order to break the model’s intended behaviour. One type of adversarial example — that many people are familiar with — are jailbreaks. Jailbreaks can generally be created even when treating the model as a black-box, knowing only that models respond differently to the contexts that they’re put in, and trying to put them in a context where they will not refuse to help the user.

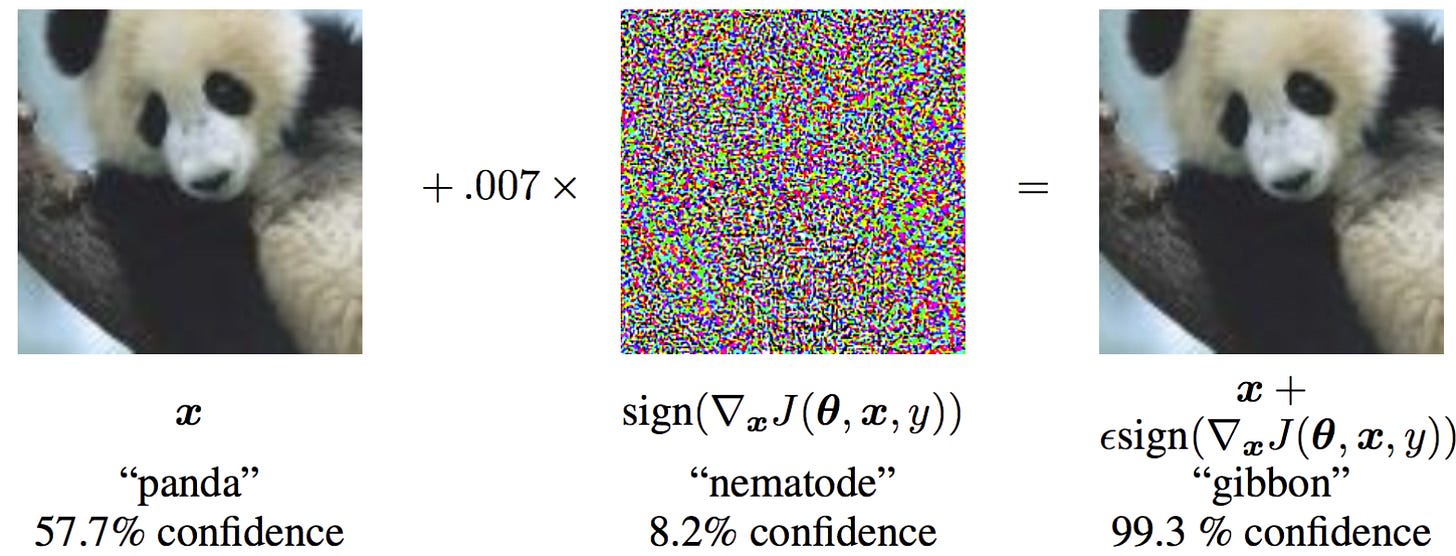

Another type of “adversarial example” are those that use full access to the model’s weights, and are specifically created in order to trigger the model into performing poorly, the classic example of this comes from image models, where adding a small amount of noise[11] to the image can cause a classifier to change categories entirely, even though the image remains easily identifiable to humans.

There are similar methods that can be applied to large language models, in order to break the model’s HHH training — in fact, we can even find examples that generalise across models, so that despite the fact that we don’t have access to GPT-5’s, or Gemini’s, or Claude’s weights, we can still apply the examples to break their safety training. Trying to train models to be robust to this is a large effort undertaken by companies at the moment, although naturally it dovetails with monitoring how users are using the model, and coming down hard on any signs of misuse (as I know all too well, having been banned from Claude for trying some risky-looking safety work, despite my girlfriend currently working with Anthropic, and having friends at the company).

Conclusion

I hope that the above has led you to think two things:

- This seems like an important problem.

- This seems like a tractable problem, or at least a problem where we can try and make things better.

The current plan for ensuring AI systems are safe is essentially a Swiss-cheese model, we’re not sure that any of of these plans is going to be a silver bullet for all of the risks laid out at the start. Hopefully with enough plans stacked on top of each other, and a lot of good people putting in hard work to make each of the plans better, we can reduce the number of holes in our layers of Swiss-cheese, and increase the number of slices of Swiss-cheese between us and catastrophe.

If you don’t like that we as a society are planning to continue developing AI despite currently having no great plan for ensuring that these models are safe — you can help! Talk to your representative — be that an MP, member of congress, or any Secretary Generals of your municipality (it really helps for politicians to hear that this is a fear shared by ordinary voters/party members). Alternatively, if the technical problems interest you, consider trying to work on them! There’s lots of great and interesting work to be done, and currently not too many people doing it!

- ^

Along with the occasional substantive breakthrough.

- ^

The current record for the nanogpt speedrun is 2.3 minutes on an 8xH100 cluster.

- ^

Section 7.2.4 here.

- ^

Note the disjunctive, not conjunctive.

- ^

Though of course there’s a lot of interdisciplinary work, as there is for each technical field I discuss in this section.

- ^

Or choose your favourite word if “want” is too anthropomorphic.

- ^

Note that this is controversial, and not every mechanistic interpretability researcher would agree with this.

- ^

Often abbreviated to HHH in the literature.

- ^

As we have seen in a number of tragic cases, mainly involving teenagers. Link to article: CW Suicide

- ^

When models agree with what the user says, whether it’s good or bad.

- ^

It’s not really noise in the usual sense of the word, because its been optimised for a specific purpose, thus removing the randomness. However, it looks random to humans.