I speak seven languages to varying degrees of proficiency. People often ask me how I learned all these languages, so I wrote the blog I wish I could send every time.

My native language is Russian. The language I live and work in is English, at about a C2, near-native level (here and later in the post, I will reference the CEFR model, which is how language levels are determined in the language learning community).

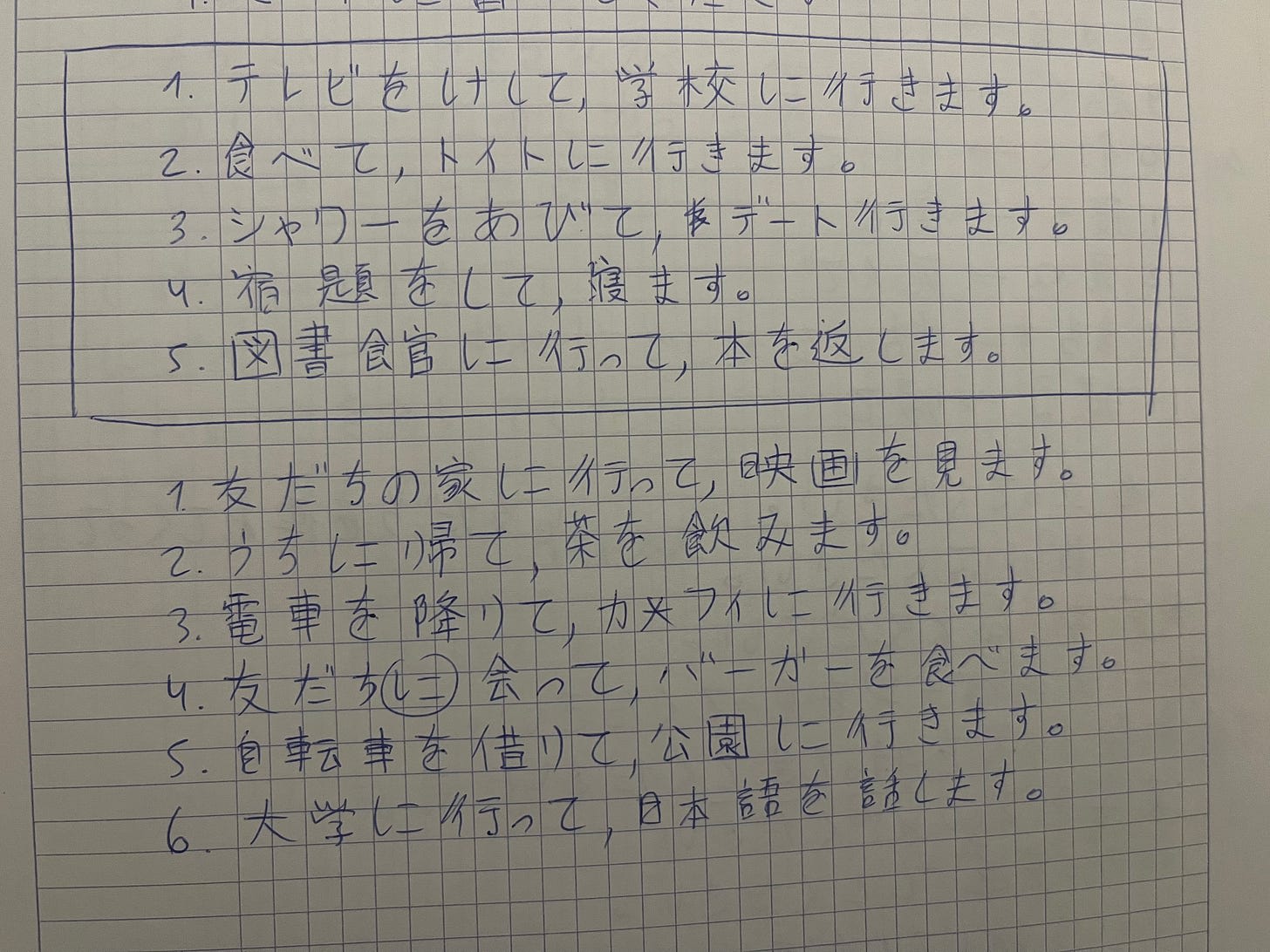

I speak Belarusian (where I grew up), Mandarin (my university degree, now intermediate, around B1-B2), Polish (from living in Poland), French and Spanish at roughly B1 to B2. I am currently learning Japanese from scratch.

Languages have changed my life. They opened doors, gave me careers, friendships, and a sense of belonging in places that would otherwise have felt foreign.

Who this guide is for

If you need languages for:

- Working or studying abroad

- Traveling

- Reading or consuming content in another language

- Talking to a partner’s family

- Feeling at home somewhere new

Then this post may be for you. My aim is to provide functional, motivating advice so as to avoid burnout or wasting time. I’m also, unusually, really into the process, so take what works for you and ignore what doesn’t.

Everything in this post comes from two places: what second-language research tends to support, and what has actually worked for me across very different languages. Those two usually line up, but they are not guarantees. People differ in motivation, time, memory, and learning style, so treat this as a strong starting point, not a rigid rulebook. I would love for you to experiment and share what you discover in the comments.

Step 1: Be brutally honest about your goal

Before you open an app or buy a book, ask:

Why do I want to learn this language?

And then test your answer against reality.

For example, many people tell me they want to learn Russian “to read Dostoevsky in the original”. Even I, as a native speaker, do not casually read Dostoevsky. That level of literary language is closer to C2 (near native, can take a decade to achieve) than B2 (upper-intermediate, fluent).

A better goal would be something like:

- “In one year, I want to travel to Japan and order food, read menus, ask for directions, and have basic conversations.”

- “I want to have casual conversations with my Spanish-speaking in-laws when we meet for dinner.”

- “I live in Germany and want to be able to work in German, which will give me more job opportunities”

Your goal determines whether you focus on speaking, listening, reading, grammar, or vocabulary, and how intensively you need to study.

If your goal is travel, you need everyday phrases and listening comprehension. If your goal is family, you need conversational fluency. If your goal is reading, you need vocabulary and grammar.

This is exactly the same logic I wrote about in my post Calibrating Your Ambition. Goals that aren’t linked to the effort you can realistically make create frustration. If you don’t choose a destination, you can spend a lot of time moving without getting where you want.

Step 2: Customise your strategy to the language

Not all languages are equally hard for every learner.

Polish was much easier for me because I speak Belarusian and Russian. The grammar is similar. Many words are familiar.

Japanese is hard for me because the grammar is structurally different from European languages (sentence order, particles, politeness). It would likely feel more familiar to a Korean speaker. On the other hand, reading is easier for me than for most beginners because I already know many characters from Mandarin.

This is why there is no universal method.

Spend a bit of time up front understanding:

- How different is this language from the ones you already know?

- What do you already have as an advantage?

- What will be genuinely new?

Today, this is easier to do with ChatGPT. You can ask it to compare your native language with your target language and suggest an optimal strategy.

That small investment can save you months of confusion.

Step 3: Start with comprehensible input

Second language acquisition research strongly suggests that we learn best when we get a lot of comprehensible input. That means listening and reading things that are just slightly above your level, where you understand most of it but not everything.

At the beginning, this usually means:

- Simple stories

- Dialogues about daily life

- Graded readers

- Slow, clear audio

Don’t be too picky at first - some stories may seem too simplified or boring. Real content is inaccessible when you know only 500 words.

The goal is always the same: to understand more today than yesterday. As a beginner, you need to build enough of a base in the language to move on to real native content that you will be more interested in.

One tool I really like for this is LingQ because it lets you read and listen, click on words to view their meaning and pronunciation, and track what you are learning in context instead of memorising lists.

You can also get a good starter book, such as Teach Yourself, which provides an introduction to grammar, culture, and basic vocabulary.

Step 4: Be consistent, not heroic

Half an hour every day beats three hours on Sunday.

Your brain learns languages through repeated exposure. It is like building a neural network. You need frequent updates.

I try to study in the morning when my brain is fresh. I also listen to audio recordings while walking my dog or doing the chores around the house.

This adds up; most days I do at least an hour a day.

Motivation from your initial goal will likely ebb and flow over time as the going gets tough, but the good news is that motivation also comes from progress. When I see myself understanding more Japanese than I did last month, I want to keep going.

Step 5: Understand how long this actually takes

This is where many people quit.

Learning a language is genuinely hard. Five minutes a day, even for years, will keep the streak alive and may be fun, but it will not make you fluent.

The US Foreign Service Institute estimates around two years of full-time study to reach professional working proficiency, roughly the B2 range, in languages like Spanish for an English native speaker. That is what most people call “fluent”.

That’s hundreds of hours, so for most people it’s a multi-year project at a few hours a day.

Languages like Japanese or Chinese take even longer for European language speakers.

Most people fail not because they are bad at languages, but because they underestimate how long the road is.

Do you need “language talent”? I don’t think so. I struggled a lot when I first learned English as a teenager. What helps now is experience: I know how to study, and I often have overlap with languages I already speak. Many people learn their first foreign language in their 20s or 30s and become fluent speakers. Some backgrounds give advantages, but consistency matters more than talent.

Step 6: Grammar, but only a little

Adults benefit from explicit grammar. However, it should not dominate.

A good ratio is roughly: 10 minutes of grammar, 40 to 50 minutes of input

Grammar helps you notice patterns. Input makes those patterns stick.

I use more explicit grammar when the structure is new (Japanese) and less when there’s overlap (Spanish via French). Later, if you want to polish accuracy, targeted grammar study can help even more.

Step 7: When to start speaking

Grammar and input build the mental model of the language. Speaking trains your ability to use that model in real time. When to start speaking will depend on your goal and the language.

With Spanish, I spoke very early because I had already studied French before, and the pronunciation was easy for me. After a few lessons, I could already communicate.

With Japanese, I am delaying speaking because I first need to understand how the language works. I do not need to speak yet for my goal, so I am not forcing it.

Speaking is most useful once you can follow the other person reasonably well. Otherwise, you spend most of the time asking for translations.

You can survive with a few hundred common words, but comfortable conversation takes thousands of words plus lots of common phrases and patterns. Vocabulary and listening depth matter more than people expect.

Many people recommend waiting until around B1 (lower-intermediate level) to speak. That is a very reasonable guideline, especially for languages which are very different from yours.

Step 8: To speak well, speak a lot

Once you can understand simple conversations, start speaking regularly.

Two or three sessions per week are enough for most goals. With harder languages, I recommend starting with 30 minutes rather than an hour.

Your tutor should:

- Let you talk

- Not correct every mistake

- Keep the conversation flowing using simple words and phrases.

Expect the first 20 hours to feel clumsy and tiring. That’s normal.

Where do you get the practice? When I was a student and didn’t have the funds for a tutor, I participated in language exchanges on websites like HelloTalk and italki. It can work well if you’re willing to help the other person with your native language, too. If you can afford to pay a tutor on recommended sites, such as italki or Verbling ($15 to $25 per session), it often saves time.

Can you use AI to practice speaking instead? In my current experience, for beginners, AI voice tools are too fast and not adaptive enough (although they can be very good for intermediate and advanced learners). With a real native speaker, there is far more accountability to practice. It can be very enjoyable to build a friendship over the course of your lessons.

Example: What actually made me fluent in English

I learned English from almost zero to a near-native level.

What did I do?

- Started with a very solid foundation of grammar and vocabulary from comprehensible input (got to about B1 level)

- Then, massive exposure to books, films, and podcasts I was interested in (3+ hours a day over 2-3 years)

- Living my life in English (I moved in with my then-boyfriend, who is from the UK, even though we lived in Belarus)

- My British partner corrected me as I spoke (at B2 and above, correction becomes useful because it polishes your language instead of blocking it).

While not everyone can get a partner just to practice their target language, you can replace this practice with a regular tutor if you can afford it, even if it ends up being a bit slower.

I didn’t use flashcards. Many people love Anki for spaced repetition, but I find it hard to stick to and prefer learning words through input.

What to do when you achieve your goal?

Most people do not need to sound native.

B1 to B2 (intermediate) is the minimum level where you could live, work at some jobs, and have relationships.

C2 (near-native), the highest level you can reach, is usually only needed if you live permanently in the country.

Decide how far you need to go, and once you get there, it’s fine to stop “studying” and just use the language.

Will you forget the language if you don’t use it? In my experience, if you’ve learned a language to an intermediate level and stopped using it, you are unlikely to completely forget it, but it will become rusty. You will find that it’s harder to speak or understand at the same level you were able to before, but if you resume input and practice, it can come back to you pretty fast.

Is it ok to still make mistakes even if you’re fluent? Yes. Even native speakers make mistakes. Most people appreciate the effort and won’t judge you, especially in languages they know are hard. As a Russian speaker, I’m always impressed when someone tries, even a little.

Speaking English at a C2 level allowed me to integrate and find work in the UK.

What I do not recommend

- Group classes: They are usually slow and inefficient for most adult learners. You get very little speaking time, and other students may be slower/faster than you, which can be very frustrating.

- Ten different apps/books: Pick one or two you like and use them consistently. Don’t be afraid to change resources if they stop benefiting you.

- Trying to memorise grammar and vocabulary perfectly: continuous input and output will eventually make these automatic, so focus on understanding and recognition over perfection.

- Forcing speaking too early: If you cannot understand, it is frustrating and unproductive.

- “Learning like a child”: Children learn through immersion, but adults have powerful analytical skills and world knowledge. You can use grammar explanations, comparisons, and conscious strategies to learn faster than a child.

- Learning from content you hate: Once you are intermediate, use content you actually care about. Try to find conversations about topics you are genuinely interested in. The best resources are the ones you want to binge on.

Resources I recommend:

I used different resources for every language I learned, but here are some general resources I found universally useful.

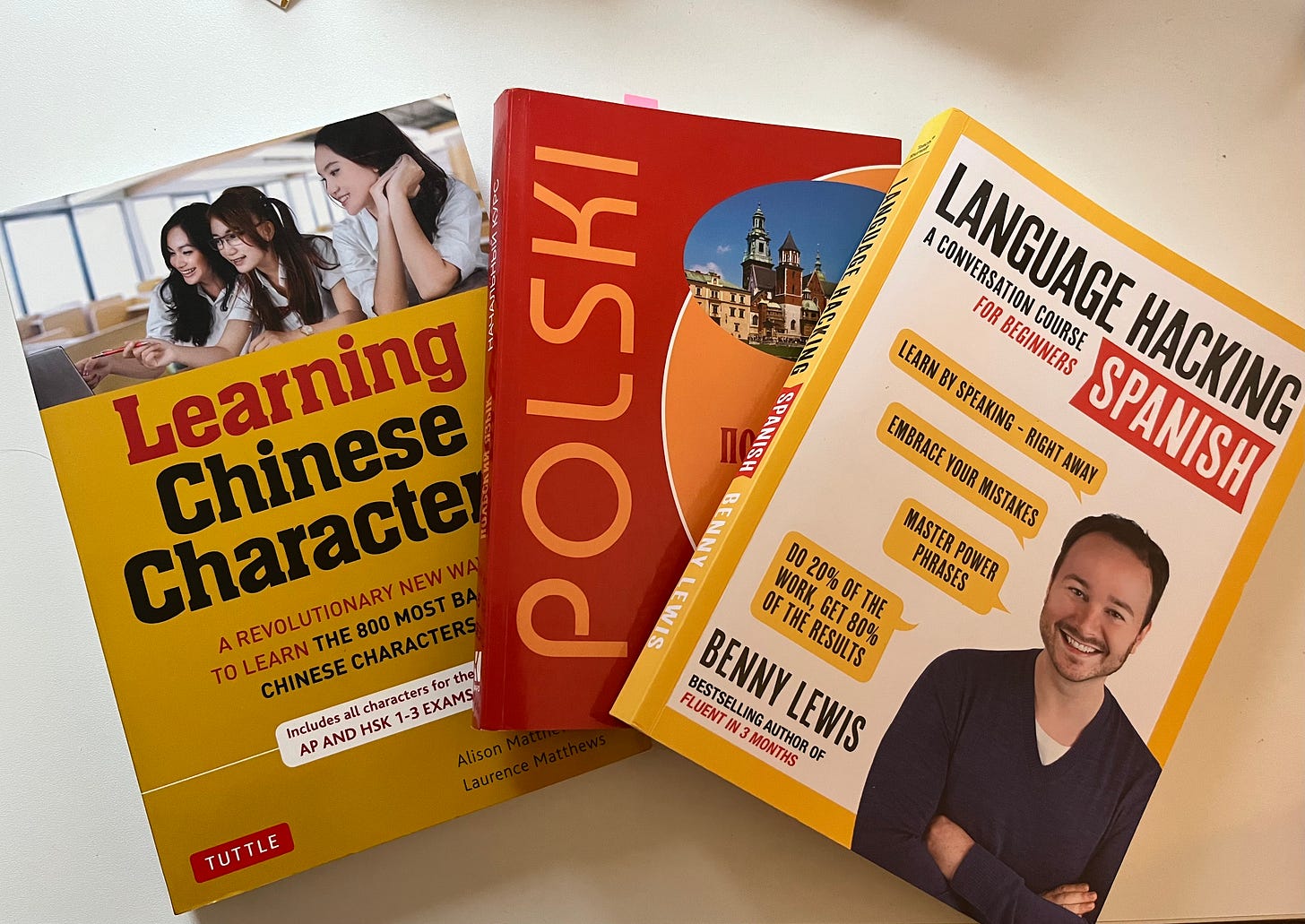

- Beginner conversation textbooks from series like Teach Yourself. I especially recommend the Language Hacking series from Benny Lewis (available in German, French, Mandarin, Italian and Spanish) - great if you need to jump to speaking fast.

- LinQ (paid) - a great platform for beginners and continuing learners, which makes reading/listening comprehension and input much easier. You can also import your own content. Made by a polyglot, Steve Kaufmann, who learned 20 languages!

- Pimsleur (paid) - speaking/listening basic, good if you don’t need reading/writing and best suited for languages with easier pronunciation. I have, however, found it a bit slow, and I do think that you need a lot of extra input in addition to the app to really understand native speakers. I also think it’s not the best value for the price.

- Easy Languages (free) - a YouTube series for many languages featuring native speakers interviewed on the street. A bit too hard for total beginners, but from A2+. There is also tons of other content on YouTube, so I recommend typing your language in and watching what you like the look of.

- Duolingo (free with ads) - I think it’s a very good app to build a habit and learn the basics, especially if you’re completely new to language learning. However, in my experience, after a few months, you need more comprehensible input to make serious progress.

- Language Reactor (free) - a Chrome plug-in that makes subtitles clickable on YouTube and Netflix. Great for binging on the content you like!

- Short stories by beginners by Olly Richards - especially if you like reading from paper books. These use simple vocabulary and grammar, although you can probably get better value and convenience from tools like LinQ.

- When you’re ready to speak, I recommend websites like italki and Verbling to book classes at affordable prices.

- If you’d like to learn more about how polyglots learn languages, you can check out these books (that said, I’d advise not to spend too much time learning how to learn a language, and more time on actually learning it.):

I am happy to share the exact resources I used for all the languages I’ve learned and what I especially liked and disliked. If you’re interested, let me know in the comments, and I can start with that language.

What’s next for me?

I’d love to continue learning languages, likely for the rest of my life. I can definitely see myself learning at least five more languages (Portuguese, Italian, Cantonese, German and Korean), and improving the languages I already speak.

To conclude this post, I’d like to share a quote by a late Hungarian polyglot Kató Lomb: “We should learn languages because language is the only thing worth knowing even poorly.”

Languages are a skill that keep giving back for the rest of your life. I hope this helps you find a way into one that fits your goals and your life.

Thanks for reading, and happy learning!

Hi, I’m Sofia Balderson. I lead Hive, a global community for people working to end factory farming. This post is from my Substack, Notes from the Margin, which I've started to share the messier, more personal reflections that don’t fit in formal updates. If you care about leading, belonging, or building something that matters (especially from the edges), you might enjoy sticking around. You can subscribe here.

Executive summary: Drawing on second-language research and her experience learning multiple languages, the author offers a practical, goal-driven guide to language learning that emphasizes realistic goals, comprehensible input, consistency, and tailoring strategies to both the learner and the language.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback