(I promise I'm not crazy!)

This post is from my blog. It was written for International Shrimpact Day/Week. It may seem like a joke, but it is not. Perhaps I could have made the same argument better, however I wanted to seriously explain some category theory and write about why shrimp matter and also make a serious argument. It's a lot of constraints, okay!

Category theory is like the poetry of mathematics. It is so general that it can be used to explain many things, but also general enough to be abused to explain anything.

It is much like Fregean logic within philosophy. Of course, it initially was introduced as a means of fleshing out mathematical statements. But it’s such a general language that it can be useful for talking about other things — it can both make those other things look more formal than they are, but also help you point out flaws in arguments. Category theory is more relational than logic, since logic presumes you’re working on the terra firma of sets — I think it could be fruitful for philosophers to learn more about category theory and use it in their work.

In this article, I hope to explain some very basic category theory, and also make a category theoretic-argument for why you ought to donate to shrimp welfare. This argument is definitely not the only good argument for why you should donate to shrimp welfare. You can disagree with this argument and think it still makes sense to donate to help stop shrimp suffering. If you’re already convinced that shrimp are morally relevant, you can donate here! It’s incredibly effective as a donation to prevent suffering in the world!

I’m hoping that, by the end of this, you will have gained a sense of how category theory works at a basic level, but also how it can be used to formalize arguments outside of mathematics. I’ll try and introduce the necessary concepts as quickly as I can, with as few examples as are necessary to communicate my point (though no less). Furthermore, in order to specify the structures I’m actually talking about[1], I am going to have to stake out claims on certain moral issues and issues of philosophy of mind[2]. However, one need not agree with me about those particular issues in order to follow the rough outline of the argument, you would just need to replace certain concepts I’m using with other concepts. I’m pretty sure my arguments would also work on many substrate-dependent accounts and on many dualist accounts. Without further ado, let’s learn some category theory!

What is a Category?

A category is an incredibly general mathematical object — it has to be, since category theorists want their results to be applicable to a wide variety of mathematical objects. All you need in order to be a category is to:

- contain objects

- contain “morphisms,” which are mappings from objects to different objects

The objects can be anything we want, but usually in category theory they are mathematical structures. You can think of morphisms as specifying a structure-preserving relation or mapping between two objects.

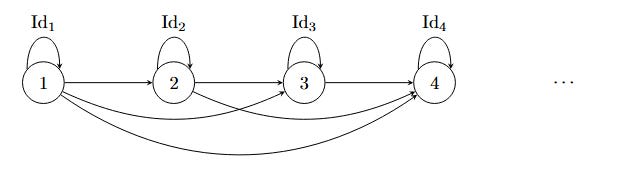

Categories can represent very simple relationships, for example we could just take the category, Num, which has whole numbers as its objects, and the morphisms represent the relation “less than or equal to.” So that our category looks like:

There always needs to be an “identity morphism” from an object to itself which we’ve included above[3]. In general, there can be more morphisms from an object to itself than just the identity morphism, or more than 1 morphism from any object to any other object — though neither of those are the case in the category above.

To be a category, we also need to be able to compose morphisms, so that if there is a morphism from 1 to 2, and a morphism from 2 to 3, there must be a morphism from 1 to 3. You can see that the diagram above does satisfy this, because 1 is less than or equal to 2 and 2 is less than or equal to 3 so also 1 is less than or equal to 3. So this is indeed a category.

The other rule that we need to follow is something called associativity. This says simply that how we decide to group operations together doesn’t matter. However, this property is pretty intuitive, and it just means that operations work how you would “expect them to,” so we’ll just breeze past it[4].

A slightly more complex category than Num, the one we gave above, is Set. This is the category of all sets[5]. The morphisms are functions between sets. So for example, you might have:

Then there are different morphisms that the arrow could represent, all valid, since there are lots of different functions from the set {1,2,3} to the set {4,5}[6]. This is a more similar category to the ones we’ll be talking about, since morphisms in our category will be some kind of function from one object to another object. I’ll note that in the category Set, the identity morphism on each set is the function that sends each element of the set to itself.

The Category of Biological Systems

I now propose a new category, the category of biological systems, which I will call BioSys. One of the objects in this category is me — I am a biological system. Another object is my dad, who is also a biological system. Another object in the category of biological systems is any shrimp (or other decapod), who is also a biological system. This category will also contain biological systems such as bacteria (though we could leave them out, and talk only about the category of possibly sentient biological systems).

The morphisms in this category are mappings between causal graphs of conscious systems that preserve a notion of qualia, if possible (there may also be more than one morphism between any two objects). These morphisms are hard to define rigorously, since we don’t really understand qualia. However, on my basic physicalist functionalist account, there is going to be some mapping from the causal structure of my brain, inasmuch as I am able to feel pain, to my dad’s brain, inasmuch as he is able to feel pain[7], that preserves the similarity between “the feeling I have when I my finger is stabbed with a needle” and “the feeling my dad has when his finger is stabbed with a needle,” along with a host of other qualia that are able to be preserved in some form between us.

I am not expecting the morphisms in this category to preserve complex feelings that might rely on specific personal data that differ between us. I am only expecting it to preserve basic immediate qualia. I believe that such a mapping is possible between all humans[8] in principle, since I believe other humans are capable of experiencing pain in a way that is extremely analogous to my experience of pain, and I think this analogy will eventually be able to be formalized in principle in some form.

In particular, I think there is also a mapping between what it is like for me to experience pain and what it is like for a shrimp to experience pain. This mapping is going to preserve less structure than a mapping between me and another human — thought I still think that this mapping exists (due to functional similarities of our respective nociceptors — i.e. pain receptors). But even if we ultimately were to determine that this mapping did not exist, it may be that there are other morally relevant types of pain that can exist in invertebrates, as is suggested by this fascinating report commissioned by my government[9]! Though I think the mapping does exist, and I will proceed from that assumption.

It is worth noting that even though what you think the morphisms themselves are will be dependent on your particular theory of phenomenal consciousness, the existence of such a category does not commit you to functionalism. The existence of the category BioSys follows only from the ability to make formal analogies between one person’s consciousness and the consciousness of another person.

What is a Functor?

A functor is a mapping from one category to another. For each “object” in the original category, a functor will associate it with a new object in the category being mapped to. Similarly, each morphism in the original category will be associated with a morphism in the new category.

A simple example of a functor can be given between our two example categories, the category of numbers, Num, with morphisms representing the “less than or equal to” relation; and the category of sets, Set, with morphisms representing functions.

We can map each number to the set containing only that number, and we can map each morphism to the unique function between those sets. Then we can say that this is a functor from the category Num to the category Set, which is written:

and this functor works as follows:

and

So that this is a valid functor. As you can see, in order to determine that a functor is indeed a functor, we just need to validate its behavior on the objects of the category, and on the morphisms of the category[10]. Let’s call this functor the Single functor — since it maps numbers to singleton sets— it will be useful later.

Functors are also extremely general objects. There were a large number of sets that had nothing mapped to them in the example above (e.g. any set containing more than one element). We don’t need to map to everything in the target category for a functor to be valid, so this is fine! It can also be the case that different morphisms in the original category map to the same morphism in the new category.

One example of how general functors can be is the “trivial” functor from any category to the "trivial category”. The trivial category looks as follows:

So that this is a valid functor. As you can see, in order to determine that a functor is indeed a functor, we just need to validate its behavior on the objects of the category, and on the morphisms of the category10. Let’s call this functor the Single functor — since it maps numbers to singleton sets— it will be useful later.

Functors are also extremely general objects. There were a large number of sets that had nothing mapped to them in the example above (e.g. any set containing more than one element). We don’t need to map to everything in the target category for a functor to be valid, so this is fine! It can also be the case that different morphisms in the original category map to the same morphism in the new category.

One example of how general functors can be is the “trivial” functor from any category to the "trivial category”. The trivial category looks as follows:

And the “trivial” functor maps every object to 1, and maps every morphism to Id₁, and this is a valid functor. It really can be as basic as that!

Two Functors From Biological Systems

There are two functors that I think are of interest for analyzing the category of biological systems, in particular as it pertains to how we should evaluate the moral worth of animals. The first is the functor from BioSys to the category Meas of measurable spaces[11]. This functor takes e.g. a shrimp brain, and views it as a system to which we can assign probabilities and discuss effect-sizes. For example, if the mathematical structure of the object in the category of biological systems were a directed graph, then the functor just takes the directed graph and maps it to a measurable space representing the different values that nodes or edges in that graph can take[12]. Then, since the morphism in BioSys is a qualia-preserving transformation, in the measurable space the functor will give us a measurable transformation from one measurable space to another, which allows us to compare properties of qualia between these different biological systems. Let’s call this functor the brain-state functor.

I know it may sound overcomplicated, to have this functor just to be allowed to assign probabilities to elements in BioSys. This is something we could do before just by assigning probabilities and describing the system, why bother with a functor?! This really is all we’re doing, and you should not overthink the functor. However, it will be useful when we introduce later concepts to recognize that we are using a functor here, so it is worth making explicit.

The second interesting functor is also between BioSys and the category of measurable spaces, Meas. This functor maps biological systems to some space on which we can evaluate their moral worth[13]. That is, it maps the system to a measure space of morally relevant mental states. Some biological systems may be mapped to an empty measurable space, as there might be nothing that is plausibly of any inherent moral worth (e.g. bacteria). Some biological systems will get mapped to non-empty measurable spaces (e.g. me, and you, and shrimp!). Then this functor transforms morphisms in the category of BioSys by turning them into measurable functions on these morally relevant mental states. This requires assuming that a biological system’s moral worth is dependent on physical facts about the biological system, a contentious assumption, but one that we will take. We will call this functor the moral evaluation functor.

You might be wondering why we’ve defined these two functors, well, this is where it gets interesting!

The Natural Transformation

A natural transformation is a mapping between functors. This is where category theory starts to get really categorical and we’re able to exploit the fact that our definitions were so general to build something interesting on top of them. A natural transformation is a way to see how one functor can transform into another functor.

It’s difficult to give a simple example of a natural transformation that doesn’t rely on mathematical knowledge[14], but I’ll do my best! Let’s first start with our category of ordered numbers, Num, from before. Let’s define a functor from the category Num into the category Set which sends each number to the product of the singleton set of that number with the set {0,1}. So that our functor looks something like this:

So the new objects are essentially the original objects product with the set {0,1}. We also need to say what the new morphisms are. Remember that the original morphisms in Num went from any number to any number that is greater than or equal to that number. After we’ve applied our functor, the new morphisms will map the lesser number to the greater number as a function on elements of sets. We need to handle the {0,1} components though, and on those we’ll just define that the function behaves as the identity. Let’s look at a quick example:

Before we applied the functor, one morphism we had was:

Which represents that 2 is less than or equal to 5. Then after applying the functor, the morphism would be:

And our new function would map (2,0) to (5,0) and (2,1) to (5,1).

This functor, let’s call it the Duplicative functor, looks very similar to the Single functor we defined between Num and Set earlier. The Single functor just mapped Num to Set without the additional product by {0,1}. Is there a way we can capture the similarity between these functors formally? Yes, we can, using natural transformations.

The natural transformation we will make will operate between these two functors from Num to Set[15]. A natural transformation will always be between functors, not between categories.

In order to specify a natural transformation, we need to specify a morphism in the category that is being mapped to (in this case, a function in the category Set) for each object in the original category Num. The natural transformation here is defined as follows:

That is, for each number in Num, the morphism we choose in Set is the function from {n} to {(n,0)}. What makes this transformation natural is the fact that it doesn’t matter in which order we perform the morphisms in the new category and the natural transformation. To spell this out in more detail:

- We could first apply the natural transformation, takins us from {n} to {(n,0)}. Then we apply a morphism in Set which we get from our Duplicative functor. This morphism maps {(n,0)} to {(m,0)} for some m which is greater than or equal to n.

- Or we could first apply the morphism in Set which we get from our Single functor, which maps {n} to {m{ for some m which is greater than or equal to n. Then we can apply our natural transformation which takes us from {m} to {(m,0)}.

Notice that, whatever order we apply them, we end up with {(m,0)} — the same thing. This is because there is some sense in which the two functors are doing the same thing[16]. This is what makes the transformation a natural transformation.

Okay, that was a lot of abstraction, is there a payoff for it?

The Payoff

Now we can turn back to the functors we defined before. These functors map from BioSys into Meas. There is a natural transformation between these two functors, the brain-state functor and the moral evaluation functor. To define this natural transformation we’ll need to assign a measurable map (i.e. a morphism in Meas) for each object in the category BioSys. This assignment will have to be such that it doesn’t matter in which order we apply the morphism and the natural transformation. We can assign a measurable maps by saying that the map for an object is the measurable map that simply forgets the non-morally-relevant qualities of the systems.

Let’s make this more concrete. This means that when we want to evaluate the moral worth of a shrimp, there are two ways we can do it, which we get from the natural transformation:

- We could take the shrimp’s brain state considered as a measurable object (as given by the brain-state functor) and then forget the non-morally relevant qualities of the system, so that it looks like the result we would get had we just applied the moral evaluation functor. Then we can map only the morally-relevant properties of a shrimp to e.g. a human, using the measurable map between the morally relevant qualities of a shrimp to a human (which we know exists from the morphism between shrimp and human in BioSys).

- We could take the shrimp’s brains state, considered as a measurable object (as given by the brain-state functor), and then compare how the shrimp’s brain state embeds into e.g. a human’s brain state. This includes all possible information, such as nociceptive circuitry, any capacity for reflection, any reflexive behavior that results from the inducement of pain. Then we forget the non-morally relevant qualities of the embedded system which is now considered as living inside a human’s brain state.

I think both of these ways to view the issue of shrimp welfare are interesting, but that most people tend to take the first viewpoint. That is to say, they consider only the morally-relevant qualities of a shrimp and then compare those morally relevant qualities of a shrimp to those of a human. This moral comparison can often be faulty, because the comparison happens after viewing the morally-relevant properties as the properties of a shrimp. In my opinion this leads people to underweight the morally relevant properties of shrimp, because of non-morally relevant properties of shrimp, such as “shrimp don’t look cute,” that affect people’s view of what the measurable map will actually be.

The second viewpoint asks you to instead first compare all the possible mental states of a shrimp with those of other biological systems. This can be those of a human, but it can also be those of a fish, or those of a lobster (which people are often reticent to see boiled alive). Once we’ve done this comparison between a shrimp and another creature across all mental states, only then do we evaluate the moral worth of the equivalent embedded properties within e.g. a lobster or a human — which of course, we tend to view as much more morally valuable. This leads more clearly to an assignment of shrimp as having some, potentially quite high, moral worth. If you think a human’s pain system has some morally relevant properties, then a shrimp’s pain system must also have some morally relevant properties, as there is some embedding from one to the other.

Conclusion

I will try not to further bore you with discussions of the functor from moral evaluations to the category of moral interventions (which I would call Interv). I will say, however, that I think interventions are orderable, and under any reasonable moral evaluations of shrimp’s welfare, the ability to save thousands of shrimp’s from agony for as little as a dollar (or a pound, or a euro) comes highly in the ordering of interventions indeed — there’s a lot of morphisms to it!

If this convinced you that it makes sense to save these shrimp for such little cost, then you can donate to help them here. Finally, I will make some brief comments on possible extensions and further investigations in the category theoretic framing for consciousness I’ve discussed here — only because I can’t help myself. I won’t explain in as much detail as I tried to do above, so feel free to skip this and go straight to donating — I think you’ve done well to get this far! It seems to me that we could instead talk about consciousness-generating properties, and then analyze whether there is a potential adjunction from the measurable space of brain-states to these consciousness-generating properties, through the category of BioSys. I think one also could take a categorical limit over the moral evaluation measurable space, and this limit will correspond to assigning consistent moral worths across different biological systems. In fact, we could even take this limit over the category of interventions itself (though we may need to add more structure than just an ordering), and this limit would correspond to a consistent moral framework for comparing actions.

I won’t conduct any of these investigations here, feel free to steal these ideas or reach out to me if you’re interested in doing that. I do wish analytic philosophers would use category theory more in their investigations, the same way they currently use logic. It seems like it could be fruitful, since there’s already such a deep categorical “bag of tricks” that philosophers could use to clarify and expand upon their explanations. It seems to me that they’re somewhat stuck in the Fregean world — which still has its place in mathematics, no doubt, but there have been developments! I am more of a logician than category-theorist by training, so the current state-of-play works better for me — but I can’t help but feel value is being left on the table here.

Finally, I’ll reiterate, I think this is not the only good argument for shrimp welfare and there are other reasons you ought to donate.

Here's that donation link again!- ^

As is necessary when we undertake an investigation in the language of mathematics.

- ^

I think I’m what you might call a physicalist functionalist, who does not believe in substrate-dependence. That is, I think consciousness arises physically and is purely a physical phenomenon, but that it arises out of an interplay of functional properties of systems, not as a result of the makeup of that system alone. I’m sure there are many great arguments against this position (some of which I already know), but it’s really not the main point of this particular essay.

- ^

And these identities make sense in this case, since 1 is less than or equal to 1! Occasionally you will see people omit these when categories are explicitly written out, to avoid cluttering up diagrams.

- ^

If it feels too intuitive to be worth mentioning, that’s because it kind of is!

- ^

There’s no set of all sets, so we can’t apply set-like reasoning to this category, since it isn’t a set. But this is okay as long as we don’t treat this object like a set.

- ^

There are precisely 8 such functions.

- ^

You could imagine constructing different types of morphisms if you’re a naturalist dualist, or a substance dualist, or believe in some form of substrate dependence. I think they will ultimately end up looking structurally quite similar to what I am proposing here.

- ^

Maybe there’s some gray areas depending on the brain structure people who have incredibly serious cephalic disorders, though I think it’s likely for there to be some mapping even in those cases.

- ^

I’m really happy that my taxes are spent on this sort of stuff!

- ^

Technically there are two other rules we need to validate for a functor, which is that the identity morphism on objects in the original category must be mapped to the identity morphism on objects in the new category, and that “functors respect composition,” so that:

That is to say, if we first compose the morphisms and apply the functor, we get the same morphism in the new category as if we applied the functor first and then composed the new morphisms. I will leave it as an exercise to show that the functor I defined between Num and Set obey this (it’s not too difficult, don’t overthink it).

- ^

I’m not going to go into detail about what a measurable space is. Just consider it a way to fully be able to describe and talk mathematically about a particular system, including the ability to define probabilities on properties of that system.

- ^

Sometimes I will switch from assigning probabilities on a particular biological system at a moment in time, which is representable by a graph and assigning probabilities on a trajectory of configurations one could imagine for a biological system. The differences between the former and the latter are not massive, so that you don’t need to worry about it too much. We can assign probabilities using a sigma algebra defined on cylinder sets on configurations, if you want a hint towards all the gory detail.

- ^

The belief that we can assign to each biological system a mapping according to its moral worth will ultimately end up implying some form of utilitarianism in the way that I will proceed to use it. However, if you don’t like assigning numbers then you could also just map it into a partial ordering, or some other structure that better represents your philosophical system. I think the same argument will go through. Or if you think there are multiple competing values, you could map to a multidimensional evaluation system. I’ve chosen the one that I personally find most plausible, which also happens to be the one that’s mathematically easiest.

- ^

If you want an example that does utilize existing mathematical knowledge then the classic example is the natural transformation from a vector space to its double dual, which has a natural transformation with the identity functor on a vector space.

- ^

A natural transformation always has to be between two functors from one category C, to another category D. If we had e.g. a functor from C to D, and a functor from C to E, we would not be able to create a natural transformation.

- ^

In fact, we can also see the sense in which the Duplicative functor really is just a duplication of the Identity functor, by seeing that there are two natural transformations here. We could instead have chosen our morphism to be:

So we have two copies of essentially the same natural transformation, this captures the duplicative nature of our Duplicative functor.

Executive summary: The author uses basic category theory to argue, in a reflective and somewhat speculative way, that once we model biological systems, brain states, and moral evaluations as categories, functors, and a natural transformation, it becomes structurally clear that shrimp’s pain is morally relevant and that donating to shrimp welfare is a highly cost-effective way to reduce suffering.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.