Summary

This post visualizes an individual’s momentary wellbeing (product of their momentary wellbeing height and depth of perception); sketches a person’s wellbeing over time; relates wellbeing activity, capacity and potential; and shows one wellbeing-adjusted life year (WALY).

Wellbeing growth sequence

- Weighted wellbeing population theory

- Wellbeing height and depth visualizations

- Visual analog scale wellbeing data gathering method

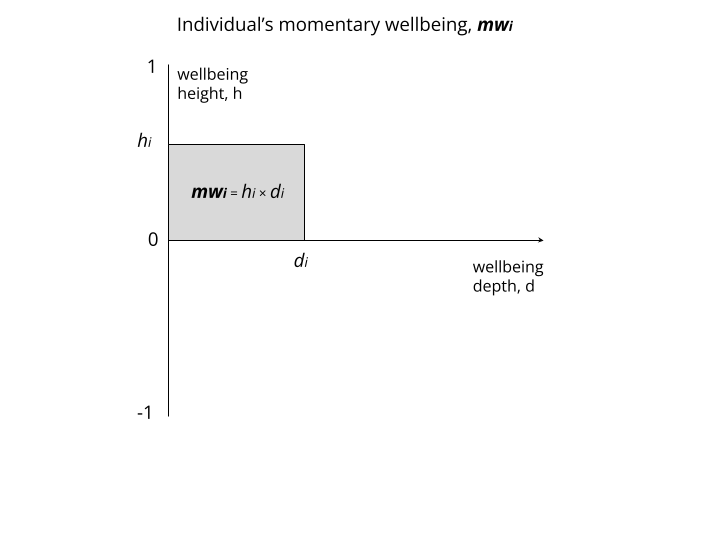

Momentary wellbeing: height × depth

Based on Jason Schukraft’s Comparisons of Capacity for Welfare and Moral Status Across Species, individuals experience wellbeing of different heights and depths. Wellbeing height measures the positiveness or negativity of the state the person experiences. Wellbeing depth describes the relative consciousness of the individual. The momentary wellbeing of an individual, mwi, can be defined as a product of their welfare height, hi, and depth, di.

The wellbeing height of an individual can take values between -1 and 1, where

- 1: the best state that any individual has ever experienced

- -1: the worst state ever experienced

- 0: neutral point, such as non-existence

Wellbeing depth can be expressed as an average (reference) awake sober relaxing human’s consciousness dulling or intensification equivalent. The reference value is 1. For example, a half-awake human can experience wellbeing depth of ½.

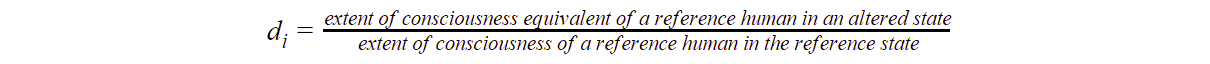

Wellbeing over time: changing height and depth

Wellbeing height and depth can change over time. Individuals can experience different positiveness and negativity of experiences as well as different consciousness states.

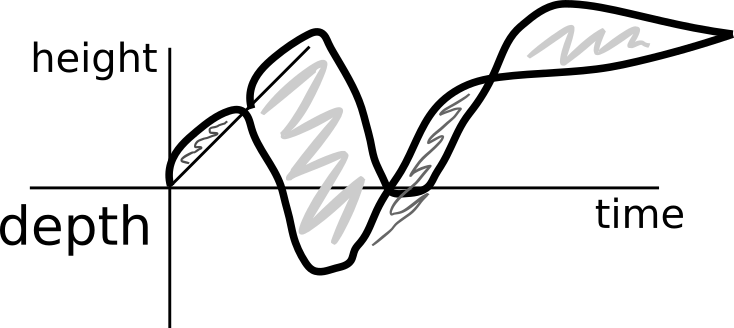

Activity, capacity, potential

At any given time, individuals experience wellbeing height and depth activity, capacity, and potential.

- Activity (value): currently experienced

- Capacity (range): possible to experience at the moment (but not experienced)

- Potential (range): would be possible to experience if past experiences were different (but is not possible)

For example, an individual can be experiencing a wellbeing height of 0.3 (activity) but could be experiencing states anywhere between -0.1 and 0.4 (capacity) at that moment. If they had different past experiences, they would be able to experience wellness height within the range of -0.2 to 0.6 (potential). Similarly, their extent of perception can be 20% of that of a reference awake human (wellbeing depth of 0.2) at present (activity), it could currently range between 0 and 0.8 (capacity) and with different prior experiences, their wellbeing depth could be between 0 and 0.9 (potential).

Wellbeing-adjusted life year:

The wellbeing-adjusted life year calculation considers wellbeing activity, because such value is subjectively perceived by individuals. However, wellbeing capacity and potential can still be considered in welfare theories.

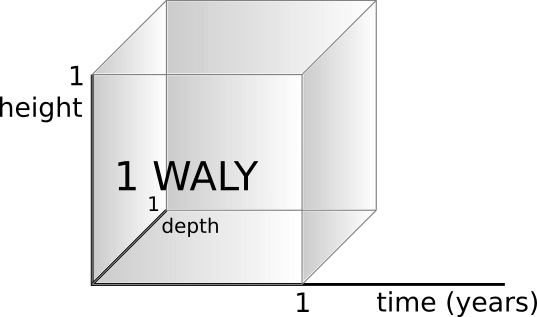

Wellbeing-adjusted life year can be defined as one year in maximum wellbeing (height = 1) experienced by the reference awake human (depth = 1).

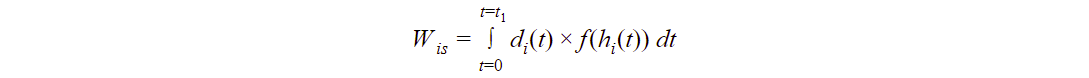

More generally, considering the possibility of non-linear weighting of wellness height and the dependence of this weighting on prior height states, but assuming constant valuation of wellbeing depth, the number of WALYs, Wis, experienced by an isolated individual over time 0–t1 can be defined as:

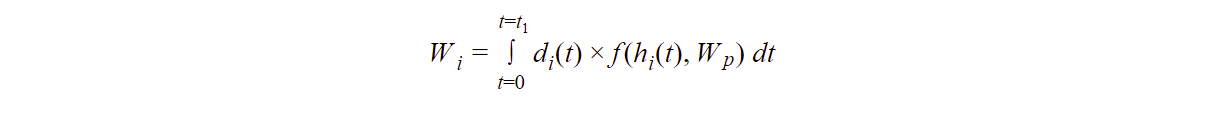

Since the valuation of an individual’s wellbeing can be dependent on the wellness of other individuals in the population, Wp the wellbeing of an individual in a population, Wi, can be expressed as:

Data smoothing may be applicable in presumably more uniform population studies (such as of caged chicken) to motivate the advancement of entire populations. However, this operation may remove important outliers within already relatively well-off systems which should be focused on or studied in particular.

DALY/QALY relevance

A synthesis of this post can be that wellness depth data can be added to the existing DALY/QALY metrics research that already includes some information on wellbeing (such as assigning disability weights to mental health conditions).

Time discounting should be discussed with relevant experts from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation in order to reasonably maximize positive impact.

In addition, various aspects that constitute one's wellbeing should be researched further and incorporated into the DALY/QALY metric computation.

Acknowledgements

I thank Jason Schukraft and Jojo Lee for useful comments on a draft of this post. I also thank Michael Plant and Geetanjali Basarkod for sharing background literature.

I'd recommend making your recent posts into a sequence, since that lets you make use of our built-in functionality for post series.

+1. These posts look really interesting, but I'm sort of missing a brief motivation section