This is a cross-post from my new blog Public Interest, which focuses on the politics and economics of global public goods. I'm starting the blog because many of the issues that the EA community prioritizes are related to global public goods. As the 80,000 hours problem profile notes, improving how we think about global public goods broadly may help us make progress on multiple cause areas at once.

Thanks to Charlie Guthmann, Juliana Conway, Raghavendra Pai, Savva Kerdemelidis, Daniella Choi, Tej Chethik, and Leigh Chethik for their comments. All opinions expressed (and any errors made) are my own.

1. Introduction to Global Public Goods Funding

Many of the most pressing problems -- such as future pandemics and climate change -- are examples of “global public goods” problems. For this reason, there’s growing discussion regarding how to best fund global public goods (including this article by 80,000 hours). Our post contributes to this conversation by assessing trade-offs between four public goods funding categories.

Before discussing the funding categories, let’s quickly describe what we mean by global public goods. Global public goods are goods/services that benefit most people in the world yet are predictably underfunded without the support of government/non-profit resources. This underfunding occurs because it’s difficult to exclude people from using a public good once it’s produced. As a result, producers struggle to receive appropriate compensation in a traditional market.

How does this play out in practice? Consider that all countries can reduce the likelihood of pandemic outbreaks by funding early detection of animal disease spillover into humans. Unfortunately, each country prefers to let other countries pay for this early detection research. Since no one actor is properly incentivized to fund this research, it continues to be underfunded according to experts. (Read here for a more technical definition of global public goods.)

So, how are global public goods funded? They’re most commonly funded upfront by governments and foundations. Much less frequently, they’re funded retroactively, via results-based financing (“RBF”). RBF involves a funder (i.e., a government or foundation) that promises to reward service providers based on the “results” of the goods/services provided.

We argue that, in many instances, RBF has advantages over upfront funding including the potential to catalyze more investment, reduce the risk of nepotism, and more effectively incentivize efficiency improvements. This blog post discusses the advantages and limitations of RBF. It concludes by discussing how RBF can help the Effective Altruism (“EA”) community and other impact-driven organizations.

2. Defining Funding Strategies

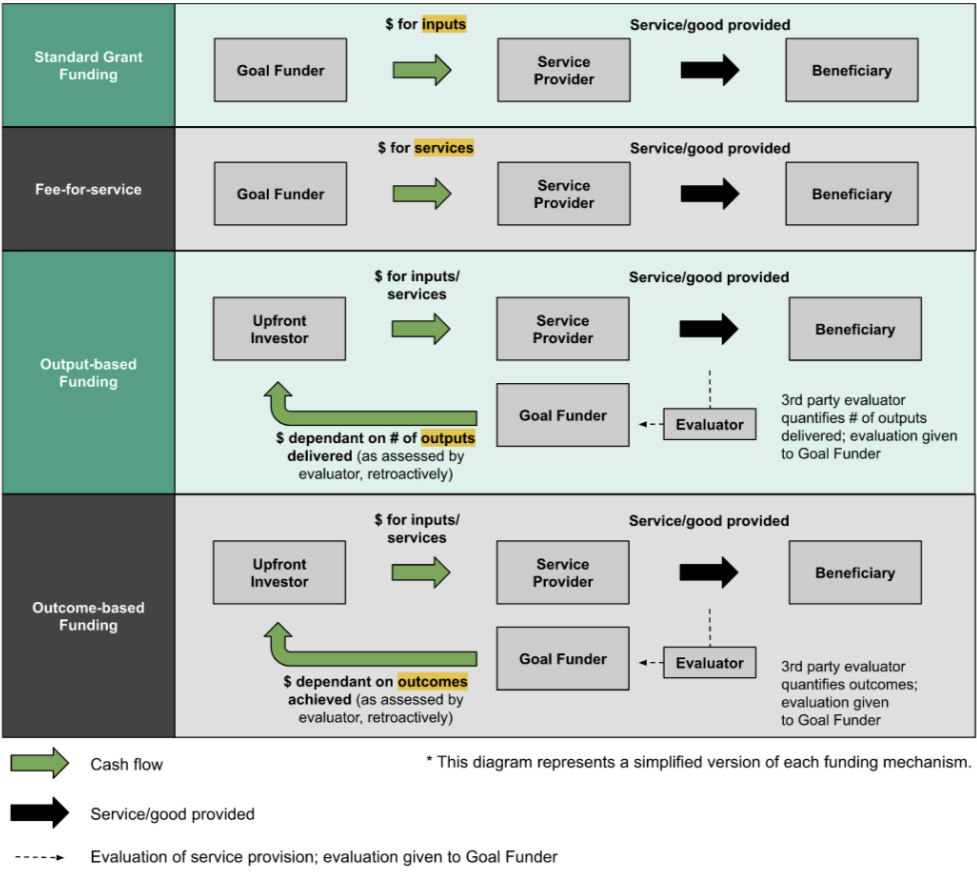

First, it’s important to understand the relevant actors:

- The “Goal Funder,” typically a government organization or foundation, picks the goods/services they wish to fund.

- When the Goal Funder uses RBF, an “Upfront Investor” funds the project, anticipating that they’ll make their money back (more on this later). Upfront Investors are usually banks.

- The entity that actually performs the service is called the “Service Provider”. Service Providers can be non-profit or for-profit firms.

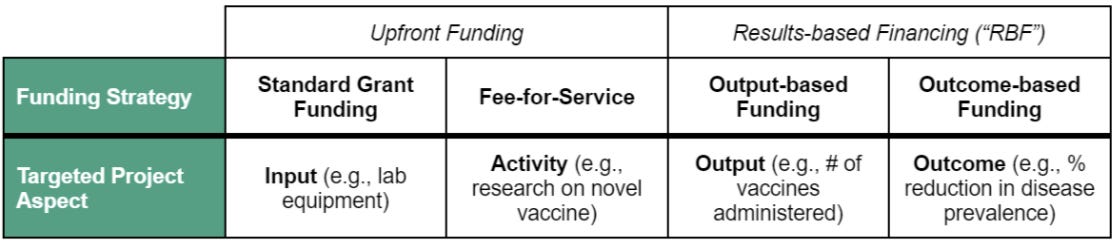

The actors use 4 broad funding strategies[1]

Upfront funding strategies

- Standard grant funding — The Goal Funder funds inputs such as lab equipment.

- Fee-for-service — The Goal Funder funds activities such as vaccine development.

RBF funding strategies

- Output-based funding — The Goal Funder promises a reward for the number of outputs produced such as the number of vaccines delivered (assessed retroactively by a 3rd party evaluator). These outputs have to meet minimum standards (e.g., efficacy standards in the case of vaccines). The Upfront Investor funds this work initially, hoping to eventually profit from the Goal Funder’s retroactive payment.

- Outcome-based funding — The Goal Funder promises a reward for the outcomes achieved such as the percentage reduction in disease prevalence (assessed retroactively by a 3rd party evaluator). Just as with output-based funding, the Upfront Investor funds this work initially, hoping to eventually profit from the Goal Funder’s retroactive payment.

See Table 1 below for a summary of what project aspect each strategy targets.

Table 1: Funding Strategies and Project Aspects

See figure 2 below for diagrams depicting how each of these funding strategies works.

Figure 1: Funding Strategies Diagram

Goal Funders can use combinations of these strategies as well. For example, sometimes a contract will primarily fund a public good via fee-for-service funding but will also offer small outcome-based incentives. Although the strategies are frequently combined, we discuss them separately to help more clearly explain the trade-offs between them.

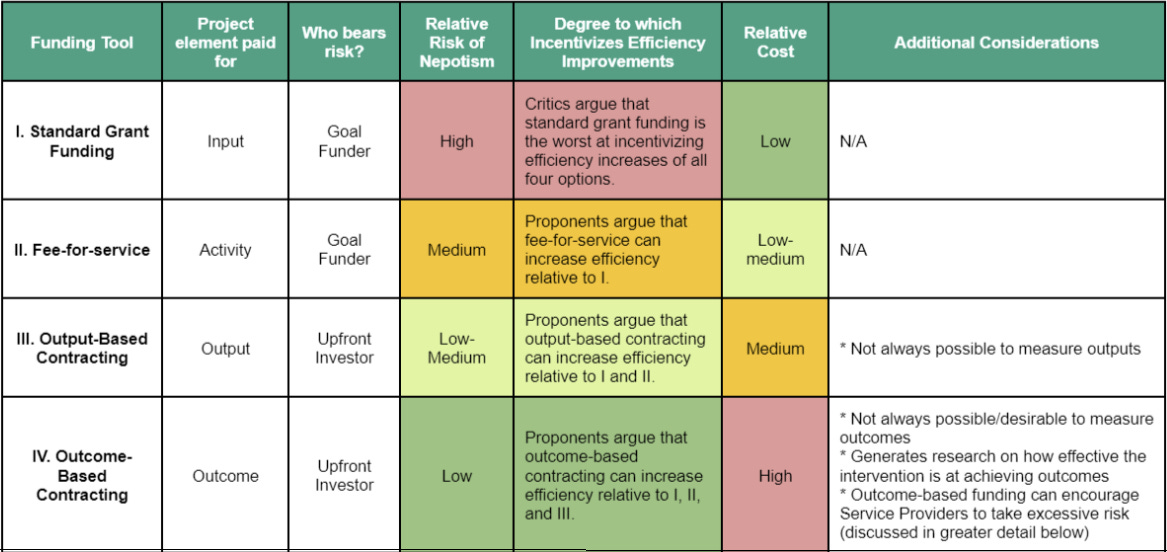

3. Assessing Tradeoffs between Strategies

We evaluate the funding strategies using four criteria -- who bears financial risk, cost, risk of nepotism, and the degree to which the strategy incentivizes efficiency improvements (summarized in Table 1 below). Our ratings are based on a quick review of research on these strategies, discussed below.

Table 2: Summary of Funding Strategies

Primary Considerations

- Who bears financial risk -- RBF enables the Goal Funder to shift financial risk and, thus, reputational risk onto Upfront Investors. Backlash for bad government funding can affect future funding but can be avoided with RBF because RBF allows Goal Funders to only pay for successful projects.

- Relative risk of nepotism -- Output and outcome-based funding forces Goal Funders to use more objective evaluation criteria. This reduces the risk of nepotism influencing funding decisions. We think nepotism, or at least public perception of nepotism, is overlooked by the EA community especially since EA grants are sometimes given to friends of the Goal Funders. Of course, this is okay to some extent -- it’s natural for people with similar values and interests to develop friendships and cross paths professionally. However, EA grantmakers should take advantage of opportunities to easily reduce the risk of nepotism/perceived nepotism when possible. RBF can help do this.

- Degree to which the strategy incentivizes efficiency improvements -- At the end of the day, Goal Funders want to maximize outcomes per dollar -- not outputs, services, or inputs per dollar. Take our vaccine example -- any Goal Funder cares more about reducing disease prevalence (outcomes) than maximizing lab equipment purchased (inputs). Outputs, services, and inputs simply serve as proxies for outcomes. Therefore, the closer the Goal Funder moves towards incentivizing outcomes, the better-aligned incentives are. Consider another example: Medicare and Medicaid (which fund national public goods, not global public goods, but still serve as a useful example). Experts argue that the historical funding strategy employed by Medicare and Medicaid -- fee-for-service -- provides limited incentive to improve quality of care and creates a perverse incentive to overprescribe services. To deal with these misaligned incentives, Medicare and Medicaid have shifted payment towards “value-based care”, which still relies somewhat on fee-for-service, but layers in output and outcome-based funding incentives (e.g., additional $ can be earned for providing customers with timely care and having low readmission rates). Early evidence in multiple fields, including medicine, suggests that RBF improves quality and reduces the price per outcome. However, further research needs to be done to understand the best use cases and practices.

- Relative cost -- The primary downside of RBF is that it costs more (at least in the short-run) than standard grant funding and fee-for-service. This is because RBF strategies require that the Goal Funder pays evaluators to measure the outputs or outcomes. Standard grant funding, on the other hand, does not require evaluators, and fee-for-service is cheap/free to assess (i.e., was the service performed or not?).

Additional Considerations

- Difficulty measuring results -- Outcomes or outputs can be difficult to evaluate due to problems defining metrics, long-time horizons, and small sample sizes. For example, how do you measure the benefits of an existential risks course, especially since class sizes are so small and outcomes may vary by teacher?

- Rigorous research is a byproduct of outcome-based funding -- Outcome-based funding requires the evaluation of programs (frequently in the form of randomized control trials). Therefore, with outcomes-based funding, Goal Funders can knock out two birds with one stone (i.e., funding a global public good AND funding research on the effectiveness of the service/good). This can be highly desirable in some cases. Crowd Funded Cures (“CFC”) is making progress on a great use case. Many experts argue that certain health interventions are predictably under-researched due to private companies’ inability to enforce the patent rights of these interventions (e.g., with repurposed generic drugs). As a result, many cheap, useful health interventions are never studied rigorously and, subsequently, never used en masse. CFC is planning to use outcome-based funding to incentivize FDA-approval-worthy research of these health interventions to improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs.

- Incentivizing risky behavior -- Some argue that since outcome-based funding cannot punish Service Providers for causing harm, it can -- unintentionally -- encourage engagement in activities with downsides (so long as the activities also have some upsides). However, this risk is somewhat mitigated because firms can be sued for harm.

4. How Results-based Financing Can Help the Effective Altruism Community and Other Impact-Driven People

- Grantmakers: Grantmakers can use RBF to increase the efficiency of positive impact work and reduce the relative risk/public speculation of nepotism. For example, in her 80,000 hours podcast interview, Dr. Cassidy Nelson suggests that creating “a design prize to see how (to) make reagents less costly” is an important strategy for reducing biorisk. A design incentive prize is a form of RBF. Additionally, RBF has the potential to reduce the risk of nepotism, which helps ensure grants are being optimally allocated and fosters public support.

- Policy Professionals: By shifting financial/reputational risk from Goal Funders to Upfront Investors, RBF can potentially enable governments to spend more. For example, EA-aligned government officials and policy researchers could encourage public school systems to develop advanced market commitments (a form of RBF) to purchase clean meat alternatives (that meet certain taste and health criteria) for school lunches. This conditional financial incentive would encourage clean meat R&D but would only cost schools money if tasty, healthy clean meat is developed. This “no risk, high reward” combination could help enable governments to spend more.

- Project Founders: Knowledge of RBF can help EA and other impact-driven organizations tap into additional funding opportunities beyond EA grants. For example, XPrize is working on a clean meat prize competition that EAs might have an interest in.[2]

- ^

These categories are adapted from Oxford’s Government Outcomes Lab work.

- ^

Broadly speaking, it may be beneficial to develop a database of prize opportunities relevant to important cause areas.

Great article! Thank you!

The quoted section surprised me a bit because (and perhaps this is only true in EAish circles, including the “randomista” movement) a lot of prospective funding is based on expensive evaluations: more leveraged priories research and RCTs but also less leveraged due diligence of particular implementing organizations. When you factor this in, retrospective evaluations can even be cheaper, depending on the field: If most projects fail in obvious ways, they don’t need to be evaluated in the first place, and if the projects produce artifacts such as research reports, it’s also very cheap to evaluate those (as opposed to, e.g., malaria incidence measures that you’d have to collect from hundreds of badly run hospitals).

FYI: I’m cofounder of GoodX (impactmarkets.io). We started out with a system that is perhaps best described as social impact bonds for high-impact research (e.g., on AI safety) and have since updated toward a system that is closer to voluntary carbon credit markets in structure but still for positive impact in general rather than just carbon removal.

Other groups in the space include Protocol Labs with their new Hypercerts Foundation and Manifund. There is also Ixo, but I don’t know them personally.