First published in 2023. Updated in 2024. Chapter 2 in the book “Minimalist Axiologies: Alternatives to ‘Good Minus Bad’ Views of Value”.

Readable as a standalone post.

1. Introduction

What are minimalist views?

- Minimalist views of value (axiologies) are evaluative views that define betterness solely in terms of the absence or reduction of independent bads. For instance, they might roughly say, “the less suffering, violence, and violation, the better”. They reject the idea of weighing independent goods against these bads, as they deny that independent goods exist in the first place.

- Minimalist moral views are views about how to act and be that include a minimalist view of value, instead of an offsetting (‘good minus bad’) view of value.[1] They reject the concept of independently positive moral value, such as positive virtue or pleasure that could independently counterbalance bads.[2]

Alleged recommendations of absurd acts

Overall, we may find minimalist views to be plausible alternatives to ‘good minus bad’ views. Yet minimalist views are sometimes alleged (at least in their purely consequentialist versions) to recommend absurd acts in practice, such as murdering individuals, or choosing not to save people’s lives, so as to prevent their future suffering.[3]

My goal here is to broadly outline the various reasons why the most plausible and well-construed versions of these views — including their purely consequentialist versions — do not recommend such acts.

For instance, in the case of purely consequentialist minimalist views, the consequentialist framework would be just as considerate of indirect, long-term effects as it would be in the offsetting versions of such views. This is worth noting because the purported absurd practical implications arguably don’t stem from minimalism itself, but from its combination with implausible interpretations of pure consequentialism.

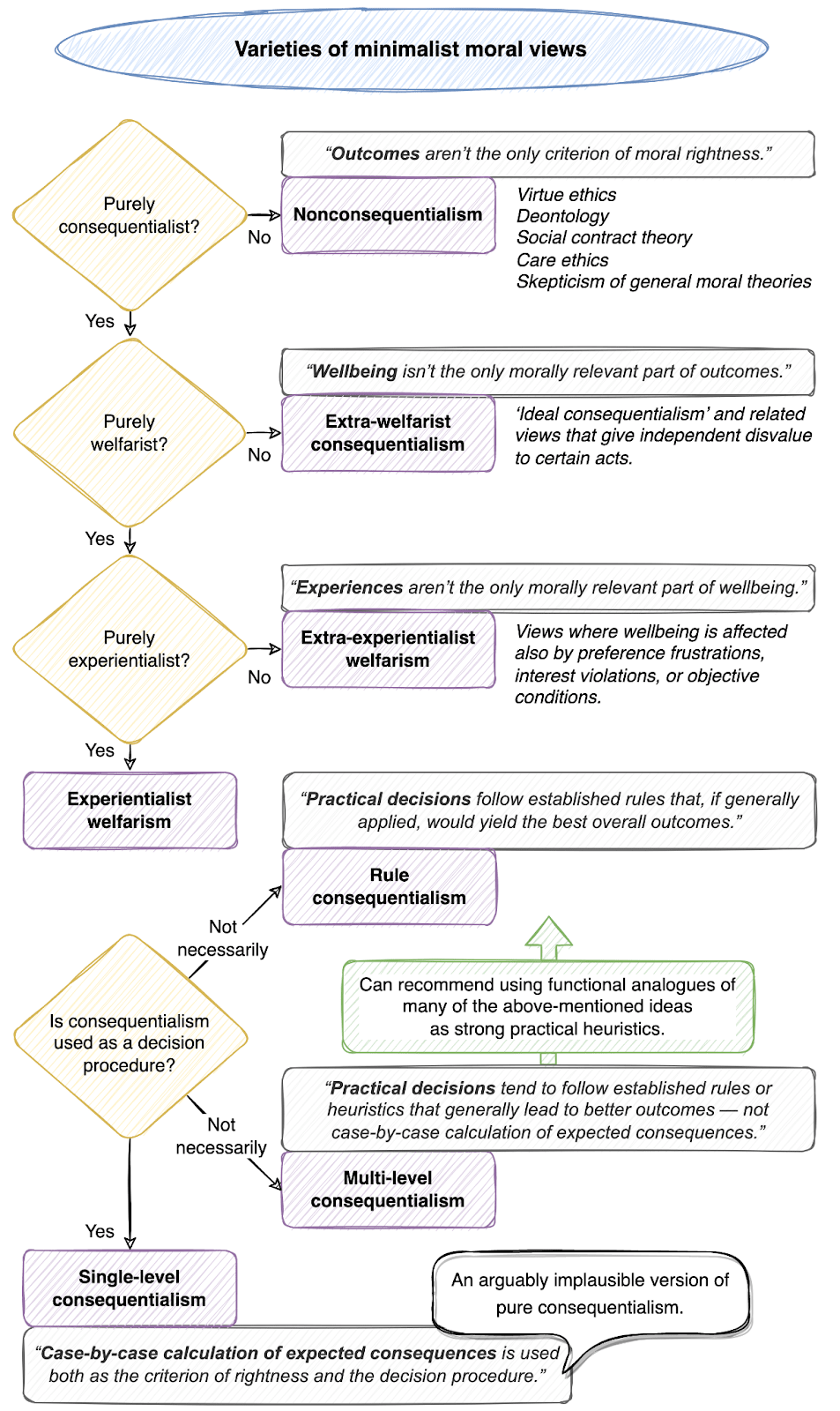

Only straight down in the diagram: Minimalist views are broader than that

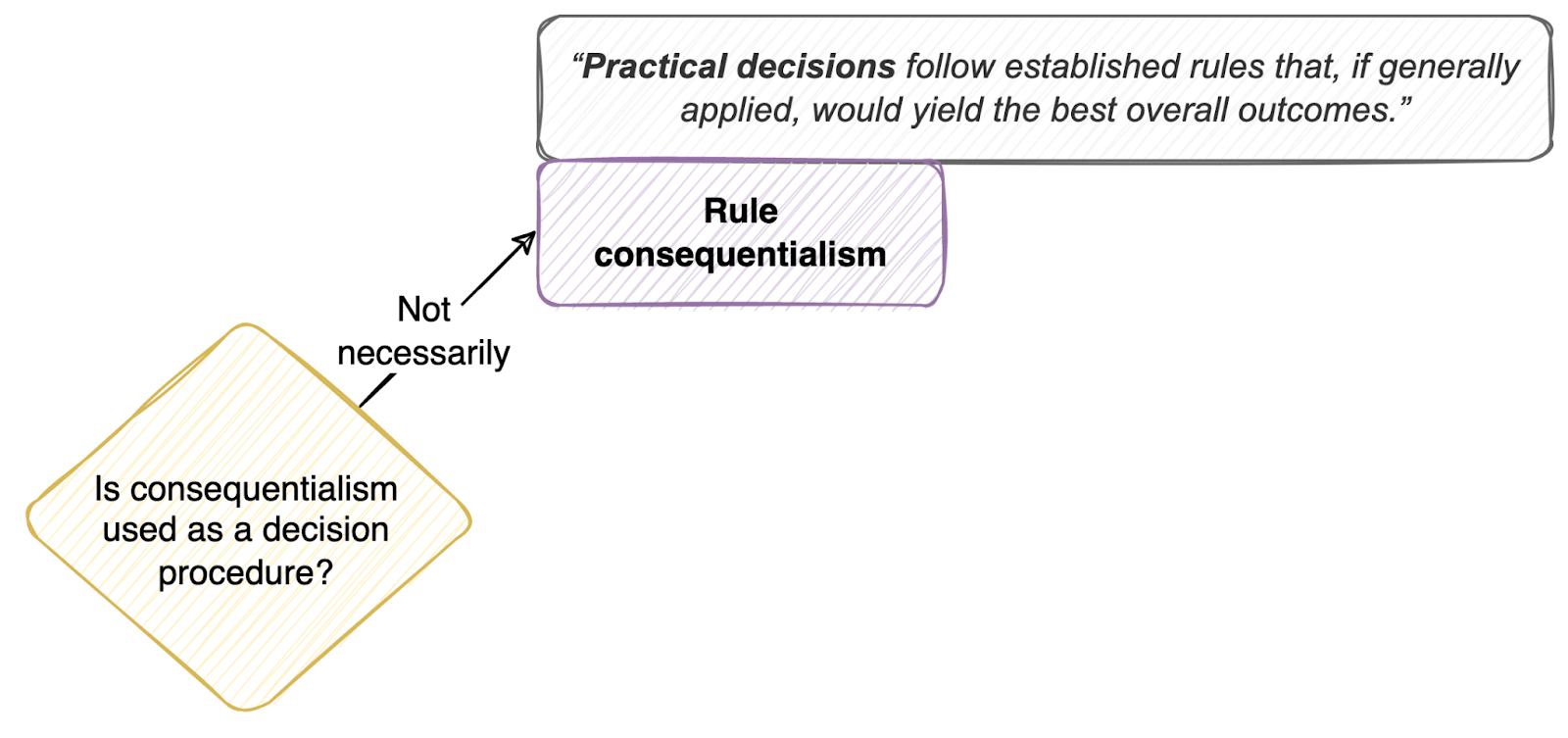

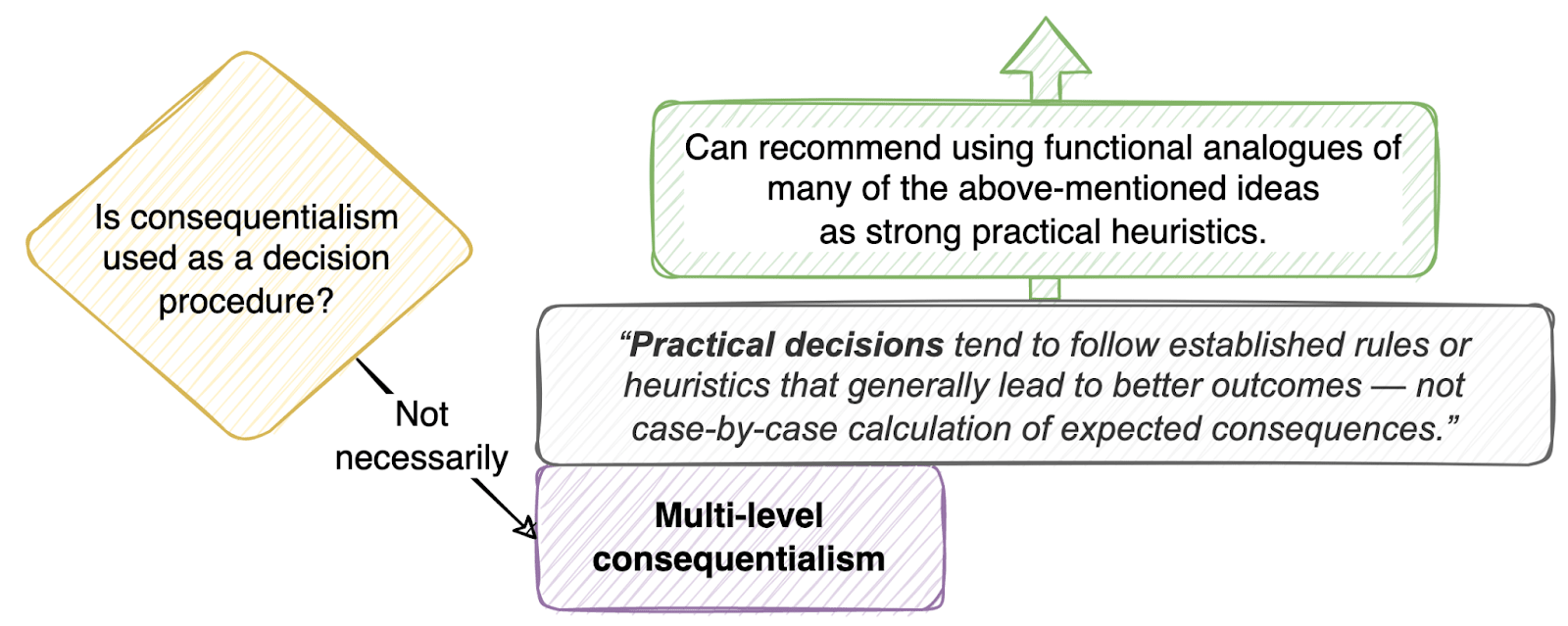

Minimalist views need not be purely consequentialist at the normative level. Similarly, purely consequentialist views need not be purely welfarist, and purely welfarist views need not be purely experience-focused. And even in the case of minimalist views that are purely experience-focused and purely consequentialist, one would still, in practice, give a lot of weight to many extra-experiential and seemingly nonconsequentialist considerations — such as the positive roles of autonomy, cooperation, and nonviolence — as part of a nuanced and impartial multi-level consequentialism (cf. Figure 2.1).

The diagram reflects the structure of this essay:

- In 2.2, I outline nonconsequentialist reasons against absurd acts.

- I focus on virtue ethics, deontology, social contract theory, care ethics, and skepticism of general moral theories.

- In 2.3, I outline consequentialist reasons against absurd acts.

- I focus briefly on extra-welfarist and extra-experientialist axiologies, namely on how such views may consider acts of violence or violation to be bad independent of their overall effects on experiential wellbeing.

- Lastly, I focus on rule consequentialist and multi-level consequentialist reasons, such as the instrumental reasons for respecting autonomy, cooperation, and nonviolence, which are relevant for all plausible minimalist moral views to the degree that they contain a consequentialist component.

2. Nonconsequentialist reasons against absurd acts

Views of wellbeing alone aren’t normative views: they don’t in themselves constitute any general principle for us to follow as a ‘criterion of rightness’ in our moral decision-making. They have normative implications for our actions only when combined with moral views whose criteria of rightness depend on wellbeing. For instance, welfarist consequentialism says that wellbeing outcomes alone determine the rightness of actions, with all other factors — such as intentions, rules, or virtues — being morally relevant only insofar as they affect the wellbeing outcomes.

I assume that all minimalist moral views would give at least some weight to how our actions affect the wellbeing of others. Thus, the consequentialist reasons against absurd acts (outlined in 2.3) can be relevant for all such views. Yet many views may also give additional normative weight to other factors, independent of the consequences of our actions. These views and factors may be seen as separate, nonconsequentialist reasons against absurd acts.[4]

Virtue ethics

Nothing stands in the way of combining a minimalist view of wellbeing or value with virtue ethics, whose central focus is the lifelong commitment to developing one’s moral character. Virtue ethics is not about seeking out any particular actions that yield the best outcomes, but about fostering a virtuous character from which the right actions would naturally follow.[5]

Imagine a moral exemplar who embodies the widely emphasized virtues of courage, kindness, honesty, and integrity. Would they sneak around, opportunistically murdering innocent individuals in the name of reducing suffering? Walk past drowning children? Sabotage healthcare?

They most certainly would not act in such ways. After all, those widely emphasized virtues are highly antithetical to such acts of backstabbing, betrayal, deception, and the like. And even in the unlikely case where one might imagine a consequentialist justification for some seemingly absurd actions, the focus of virtue ethics remains not on any particular actions, but rather on the continuous cultivation of an unfailingly virtuous character, avoiding deviation from the path of highest virtue.[6]

Deontology

A minimalist view may also be combined with deontology, where right action is determined by adherence to a set of moral rules or duties.[7] For instance, deontology can entail a commitment to non-maleficence (“do no harm”), the golden rule (“treat others as you wish to be treated”), or respecting certain inviolable rights that apply universally to all individuals, such as the right to autonomy.

Deontological commitments often directly oppose the kinds of extreme actions that a purely consequentialist analysis might otherwise justify as stepping stones to better outcomes. Consider severe rights violations aimed at hastening the termination of lives that are perceived to have negative welfare. Regardless of whether such actions would practically lead to better outcomes, deontology rejects that outcomes are the full picture of what matters morally. Instead, it holds that our actions should primarily align with our duties, which often contradict what may seem justified in the edge cases of purely consequentialist reasoning.[8]

Social contract theory

Similarly, one may endorse minimalist versions of social contract theories, which derive moral norms from a hypothetical agreement conceived through rational deliberation (a “social contract”). Social contract theories center around the idea of consensus among rational agents, implying that an action is morally wrong when it violates the norms of this hypothetical consensus.[9]

Imagine a diverse set of people, endorsing a minimalist view of wellbeing, who deliberate on the moral principles governing their society. Would they endorse norms that allow callous acts like murder, passive bystanderism, or attempting to collapse the healthcare system? It seems doubtful that they would endorse the kind of chaotic and unsafe society where such unilateral choices were acceptable.

More likely, they would converge on impartial, predictable norms of justice, trust, and respect for everyone’s autonomy, with a focus on cooperatively minimizing severe problems like extreme suffering, violence, and violation. By contrast, the callous acts in question seem like textbook examples of breaching the social contract.[10]

Care ethics

Compared to the previous views, care ethics is less abstract and universalistic, and more concrete and contextualistic. A core idea in care ethics is that individuals are fundamentally relational and interdependent beings, with ethical obligations arising from relationships. It is focused on attentive, empathetic, and proactive responsiveness to the needs of others, particularly within relationships of care and dependency.[11]

A minimalist version of care ethics would naturally focus on anticipating and addressing the unmet needs of others, without necessarily assuming that their primary concern would be anything like minimizing personal suffering. Rather, it would plausibly involve attending and responding to others on their own terms, with sensitivity to their own goals and pursuits in life.[12] Thus, minimalist care ethics would likely oppose any acts that fail to respond to others in a caring way, such as acts of murder, betrayal, or being insensitive to the subjective perspectives of others.

Skepticism of general moral theories

Various philosophers doubt the idea of a universal moral criterion that would apply to all actions in all situations, often highlighting the complexity or context-sensitivity of morality.[13] They may argue that a universal ethical framework will inevitably oversimplify ethics, or that there is no pressing need for such a framework.

A comparison could be made to how physicists use different physical theories in different domains of applicability, reflecting the complexity of physical phenomena. Similarly, one may find some moral theories plausible and applicable in some domains, yet doubt that any single moral theory could fully capture the complexity of all moral phenomena across all domains.

For example, Simon Knutsson combines a minimalist view of wellbeing and value with skepticism of overarching moral theories.[14] The resulting moral view does not generate the alleged absurd implications often falsely attributed to minimalist views of wellbeing or value, as it is not tied to any moral theory that would generate such implications.

In sum, while purely consequentialist views deem outcomes the sole criterion of moral rightness, we may also — to the degree that we find it plausible — give independent normative weight to other factors, such as character, duties, agreements, or empathetic responsiveness in our relations with others.[15]

3. Consequentialist reasons against absurd acts

The following reasons against absurd acts relate to varieties of purely consequentialist minimalist views, but also to all other views that give some normative weight to the relevant assumptions, namely:

- extra-welfarist disvalue,

- extra-experiential components of wellbeing,

- rule consequentialism, or

- multi-level consequentialism.

Axiological reasons

This section covers views that may consider acts of violence or violation to be bad — in themselves, or for the victim — independent of their overall effects on experiential wellbeing.

Extra-welfarist axiologies

Even if consequentialist views agree that the rightness of actions is determined solely by the value of outcomes, they diverge in what they define as the morally relevant parts of outcomes. Only purely welfarist views hold that the value of outcomes is based solely on the wellbeing they contain. By contrast, some forms of ideal consequentialism hold that certain acts have intrinsic value or disvalue, independent of their overall effects on wellbeing.[16]

Minimalist versions of ideal consequentialism wouldn’t count any acts as intrinsically good or valuable. Yet certain acts would have independent disvalue, thereby decreasing the value of outcomes. For instance, acts like murder or betrayal could in themselves constitute severe bads, and hence count among the very phenomena to be minimized.[17]

Extra-experientialist welfarist axiologies

We have seen how the scope of morally relevant phenomena can be broader than “only consequences” (according to nonconsequentialist views), and how the scope of relevant consequences can be broader than “only effects on wellbeing” (according to extra-welfarist views). Similarly, even if we do assume a purely welfarist consequentialist view, the scope of what we find relevant for wellbeing can be broader than “only conscious experiences”.

While experientialist minimalist views (1.3.1) define wellbeing as the degree to which we are free from experiential sources of illbeing (like suffering, disturbance, or a visceral non-acceptance of our current experience), minimalist versions of extra-experientialist views (1.3.2) may additionally hold that we can be severely harmed by factors outside our immediate experience (like unmet preferences, violated interests, or objective conditions).[18]

If we combine welfarist consequentialism with these broader views, it follows that we should reduce not only felt harms, but also harms like premature death, failed life projects, and being subjected to violence. This adds another layer of opposition to the absurd alleged implications that people sometimes associate with minimalist views of wellbeing or value.

Rule and multi-level consequentialism

Consequentialist views need not recommend case-by-case calculations of the expected outcomes of every single action. This is often cognitively demanding, time-consuming, or even impossible, and hence practically counterproductive by consequentialism’s own lights.

Instead, some versions of consequentialism provide clearer and more practical guidance for action by focusing on general rules or heuristics to follow. These rules or heuristics can capture the wisdom of past experiences, codifying patterns of action that generally lead to better outcomes.

Rule consequentialism

Rule consequentialism deems actions right if they follow rules that, when generally applied, yield the best overall outcomes.[19] Unlike deontology and social contract theory, it selects rules based solely on their expected consequences. Yet all three evaluate the moral rightness of individual actions by rule adherence rather than case-by-case consequences.

Minimalist rule consequentialism would strongly oppose acts like unprovoked murder or severe and unprovoked rights violations, as the allowance of such acts is prone to overall increase rather than decrease the amount of problems in the world. At worst, general rules that allowed such acts would risk leading to catastrophic futures. After all, increased conflict and hostility among future actors is a key risk factor for worst-case outcomes — namely, worlds defined by ruthless competition, adversarial dynamics, and escalations that bring out the worst tendencies for hatred, vengeance, and sadism.[20]

Rather, the best general rules to adopt will most likely involve a proactive protection of people’s lives and safety, in part because that is arguably the best way to secure and develop our shared capacity to solve problems in cooperative ways.

Multi-level consequentialism: Relevant for all minimalist moral views

Multi-level consequentialism merges act-based and rule-based approaches, providing a layered approach to consequentialist decision-making.[21] It ties the rightness of actions to their overall consequences, yet only recommends that we attempt to estimate the consequences of individual actions in the arguably rare, ‘critical’ situations where this is plausibly worth the effort. These could be the occasional high-stakes situations where our established heuristics deeply conflict, are silent, or might lead to highly suboptimal outcomes, prompting a switch to the more analytical level of moral reasoning.

In situations where such detailed analysis is impractical, the multi-level approach recommends the ‘intuitive’ decision procedure of following established heuristics that generally lead to better outcomes. These heuristics can often be inferred and justified at the analytical level given our past experiences and knowledge. Yet consequentialists need not reinvent all the moral wheels of society, because a highly sensible meta-heuristic (by consequentialism’s own lights) is to assign significant weight to the long-standing recommendations of other ethical views and established norms in typical moral decisions — at least when these recommendations strongly converge to discourage certain types of actions.[22]

If we want to effectively reduce problems in the big picture, the multi-level approach also recommends that we mostly focus on the kinds of positive, constructive goals that best enable us to collectively prevent problems like extreme suffering — a multi-generational, shared endeavor that requires greater levels of coordination and cooperation, and which requires us to avoid and actively prevent absurd acts.[23] And since all the minimalist moral views discussed here give at least some weight to minimizing the badness of outcomes, this is (an added) reason for all people with such views to oppose absurd acts.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for helpful comments by Simon Knutsson and Magnus Vinding.

References

Alexander, L. & Moore, M. (2021). Deontological ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological

Ashford, E. & Mulgan, T. (2018). Contractualism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/contractualism

Baumann, T. (2019/2022). Risk factors for s-risks. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/risk-factors-for-s-risks

Brennan, S. M. K. (1988). Ideal utilitarianism (Doctoral dissertation). University of Iowa. philpapers.org/rec/BREIU

Cudd, A. & Eftekhari, S. (2021). Contractarianism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/contractarianism

Ewing, A. C. (1948). Utilitarianism. Ethics, 58(2), 100–111. doi.org/10.1086/290597

Hooker, B. (2023). Rule consequentialism. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/consequentialism-rule

Hursthouse, R. & Pettigrove, G. (2023). Virtue ethics. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/ethics-virtue

Häyry, M. (2024). Exit Duty Generator. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 33(2), 217–231. doi.org/10.1017/S096318012300004X

Knutsson. S. (2022a). Pessimism about the value of the future and the welfare of present and future beings based on their acts and traits. simonknutsson.com/pessimism-value-future-welfare-acts-traits

Knutsson, S. (2023a). My moral view: Reducing suffering, ‘how to be’ as fundamental to morality, no positive value, cons of grand theory, and more. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/my-moral-view-reducing-suffering-by-simon-knutsson

Mayerfeld, J. (1999). Suffering and Moral Responsibility. Oxford University Press. goodreads.com/book/show/2438988

Ord, T. (2013). Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian. amirrorclear.net/academic/ideas/negative-utilitarianism

Orsi, F. (2012). David Ross, Ideal Utilitarianism, and the Intrinsic Value of Acts. Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy, 1(2). doi.org/10.4148/jhap.v1i2.1348

Ridge, M. & McKeever, S. (2023). Moral particularism and moral generalism. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/moral-particularism-generalism

Vinding, M. (2020d). Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications. Ratio Ethica. magnusvinding.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/suffering-focused-ethics.pdf

Vinding, M. (2022f). Point-by-point critique of Ord’s “Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian”. centerforreducingsuffering.org/point-by-point-critique-of-why-im-not-a-negative-utilitarian

Vinding, M. (2022g). Reasoned Politics. Ratio Ethica. magnusvinding.files.wordpress.com/2022/03/reasoned-politics.pdf

Vinding, M. (2022j). Some pitfalls of utilitarianism. magnusvinding.com/2022/11/25/some-pitfalls-of-utilitarianism

Vinding, M. (forthcoming). Compassionate Purpose: Personal Inspiration for a Better World. magnusvinding.com/books/#compassionate-purpose

Notes

- ^

Cf. 1.2.

- ^

Others may define “minimalist moral views” more broadly to include views that reject independently positive or offsetting moral value without endorsing minimalist axiological claims of any kind (e.g. views that lack an axiology). Such views might include versions of fully nonconsequentialist views that entail only moral claims that are “minimalist in flavor”, such as that we have moral reasons to reduce vice, harm, violations, and so on.

- ^

For instance, an influential yet misleading essay by Toby Ord (2013) contains the following claim:

[Negative utilitarianism, a consequentialist view focused on the minimization of suffering] implies that much healthcare and lifesaving is of enormous negative value. It says that the best healthcare system is typically the one that saves as few lives as possible, eliminating all the suffering at once. This turns healthcare policy debates on their heads and means we shouldn’t be emulating France or Germany, but should instead look to copy failed states such as North Korea.

(This and other misleading claims in Ord’s essay are given a point-by-point reply in Vinding, 2022a.)

- ^

For some context regarding how widely endorsed these nonconsequentialist views are, it is worth noting that among the respondents of the 2020 PhilPapers survey (of 1741 English-speaking philosophers from around the world), only a fifth were exclusively favorable toward pure consequentialism (survey2020.philpeople.org/survey/results/4890):

• 37% leaned toward virtue ethics (25% exclusively);

• 32% toward deontology (20% exclusively);

• 31% toward consequentialism (21% exclusively);

• 16% for combined views;

• 6% for alternative views.

The responses among normative ethicists (n = 358) indicate similar or even broader support for nonconsequentialist views (survey2020.philpeople.org/survey/results/4890?aos=30):

• 38% leaned toward virtue ethics (21% exclusively);

• 41% toward deontology (23% exclusively);

• 30% toward consequentialism (20% exclusively);

• 22% for combined views;

• 10% for alternative views.

- ^

Cf. Hursthouse & Pettigrove, 2023.

- ^

As mentioned in 1.3.2.3, one may see virtue as the absence of vice.

- ^

Cf. Alexander & Moore, 2021.

- ^

Analogous to the case of minimalist virtue ethics: Minimalist deontology would see rule adherence as the absence of rule violation. To fulfill one’s duties is to not fail at them, but does not constitute an offsetting moral good.

- ^

- ^

While rational agents might converge only on a relatively narrow range of acceptable means for reducing extreme suffering, there’s still good reason to assume that they would give strong priority to the underlying aim of reducing extreme suffering. A contractualism-based argument for the latter claim is found in Vinding, 2020d, sec. 6.7. Similarly, Mayerfeld (1999, p. 115) identifies a contractualist justification for the duty to relieve suffering as follows:

… reasonable moral rules are those that would be chosen by people made temporarily ignorant of their life circumstances [i.e. behind the ‘veil of ignorance’]. … People who could not predict the extent of their vulnerability to suffering in real life might seek protection from the worst eventuality by agreeing on a strong requirement to relieve suffering.

- ^

- ^

Given this sensitivity to individuals’ own goals and pursuits, it may be natural to combine a minimalist version of care ethics with a minimalist preference-based view of wellbeing (1.3.2.1).

- ^

Cf. Ridge & McKeever, 2023.

- ^

Knutsson, 2023a.

- ^

The factors can also be combined in various ways. For instance, one may combine them into “overarching pluralist theories”, where factors like different virtues and duties all play an advisory role in all of one’s moral decisions. Alternatively, one may combine them into skeptical or particularist views, where no single aspect of morality is universally applicable, yet many may have their own domains where they best apply.

- ^

- ^

A minimalist view that assigns disvalue to acts is introduced and defended in Knutsson, 2022a, though note that Knutsson’s moral view is not consequentialist.

- ^

The 2020 PhilPapers survey polled global English-speaking philosophers on wellbeing views. Of the 967 respondents, most seemed to agree that wellbeing can be negatively affected by things outside our experience, as only 10% favored experientialism exclusively (survey2020.philpeople.org/survey/results/5206):

• 53% leaned toward objective list views (50% exclusively);

• 19% toward desire satisfaction/preferentialist views (15% exclusively);

• 13% toward hedonism/experientialism (10% exclusively);

• 5% for combined views;

• 5% for alternative views.

Among the 244 normative ethicists (survey2020.philpeople.org/survey/results/5206?aos=30):

• 64% leaned toward objective list views (59% exclusively);

• 15% toward desire satisfaction/preferentialist views (12% exclusively);

• 11% toward hedonism/experientialism (9% exclusively);

• 6% for combined views;

• 8% for alternative views.

There were weak correlations between consequentialist and experientialist views (r = 0.26), between consequentialist and preferentialist views (r = 0.19), and an inverse one between consequentialist and objective list views (r = -0.29). This indicates that academic philosophers broadly endorse various combinations of normative and wellbeing views, including extra-experientialist versions of consequentialist views. (A minimalist example might be the need-based view of Häyry, 2024, which is about reducing “pain, anguish, and dwarfed autonomy”.)

- ^

Hooker, 2023.

- ^

Baumann, 2019, “Conflict and hostility”.

- ^

Multi-level consequentialism has more often been discussed under “two-level consequentialism” or “two-level utilitarianism”, as developed by R. M. Hare.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consequentialism#Two-level_consequentialism; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-level_utilitarianism.

- ^

Cf. Vinding, 2022c, “A more plausible approach”:

In other words, it seems that utilitarian decision procedures are best approached by assigning a fairly high prior to the judgments of other ethical views and common-sense moral intuitions (in terms of how plausible those judgments are from a utilitarian perspective), at least when these other views and intuitions converge strongly on a given conclusion. And it seems warranted to then be quite cautious and slow to update away from that prior, in part because of our massive uncertainty and our self-deceived minds. This is not to say that one could not end up with significant divergences relative to other widely endorsed moral views, but merely that such strong divergences probably need to be supported by a level of evidence that exceeds a rather high bar.

Likewise, it seems worth approaching utilitarian decision procedures with a prior that strongly favors actions of high integrity, not least because we should expect our rationalizing minds to be heavily biased toward low integrity — especially when nobody is looking.

Put briefly, it seems that a more defensible approach to utilitarian decision procedures would be animated by significant humility and would embody a strong inclination toward key virtues of integrity, kindness, honesty, etc., partly due to our strong tendency to excuse and rationalize deficiencies in these regards.

- ^

Vinding, 2022g, chap. 9, “Identifying Plausible Proxies”; forthcoming, sec. 6.3, “Focusing on Positive and Constructive Goals”.

These arguments all seem to be relying on using widespread support for traditional moral theories to attempt to cover up the absurd recommendations of negative utilitarianism. But the same intuitions that make some people support negative utilitarianism would probably mean people should support inverted versions of standard moral theories also.

For example, you claim that virtue ethics would stop negative utilitarians from killing people:

But a true negative utilitarian might not regard killing someone as backstabbing; rather, he would think his is being an agent of mercy, heroically protecting innocent people from the suffering of existence by providing them the sweet embrace of death.

Likewise, you suggest that deontology might protect us:

But a negative deontologist would presumably have a different interpretation of these what should be the rules. Since there are no positive goods, painlessly killing a homeless person in her sleep wouldn't cause harm and hence not be forbidden. Similarly, since he thinks life is just gradations of suffering, a swift death would sound quite favourable to him, so treating others to the same would not be a big violation of the golden rule.

Similarly, your negative utilitarians, in their deliberations, seem to agree on a vision of society which does not include much negative utilitarian influence:

If these people really wanted to agree on a set of rules to govern a society, I agree they wouldn't want to promote chaos. Instead, presumably they would focus on stockpiling enough cyanide to allow for a simultaneous mass suicide.

Similarly, you suggest that care ethics could protect us:

But again this basically relies on a conventional account of care ethics. The negative utilitarian, on the other hand, would presumably be primarily focused on anticipating and addressing the unmet needs of others for relief from suffering. The same reasons that made him reject conventional utilitarianism in favour of the negative kind would suggest that he should prioritise her unmet need for the cessation of pain. It's already the case that people will sometimes support and enable euthanasia for sick loved ones, but for most people this is only a small part of what caring means.

In the interests of brevity I will pause here, but I'm sure you can see the issue. In each example you suggest that follower of negative utilitarianism would resist the more absurd implications of NU because he would have various other moral commitments that temper his fervor. But it seems like this relies on a profound lack of moral curiousity on his part, of his not re-examining his other moral commitments. Each of these has its own negative flavour he could adopt, and the same reasons that made him endorse negative utilitarianism seem like they would also encourage negative versions of the other moral commitments, and hence not provide the moderating influence we might want.

Greetings. :) This comment seems to concern a strongly NU-focused reading of the nonconsequentialist sections, which is understandable given that NU, particularly, its hedonistic version, NHU, is probably by far the most salient and well-known example of a minimalist moral view.

However, my post’s focus is much broader than that. The post doesn’t even mention NU except in the example given in footnote 2, and is never restricted to NHU (nor to NU of any kind, if the utilitarian part would entail a commitment to additive aggregation). For brevity, many examples were framed in terms of reducing suffering. Yet the points aren’t restricted to hedonistic views, as they would apply also to minimalist moral views with non-hedonistic views of wellbeing. And if we consider only NHU, then the most relevant sections would be the ones on minimalist rule and multi-level consequentialism.

The comment seems to assume that the minimalist versions of {virtue ethics / deontology / social contract theory / care ethics} would have their nonconsequentialist moral reasons grounded in NHU. Yet then they wouldn’t contain genuinely nonconsequentialist elements, but would rather be practical heuristics in the service of NHU. My main point there was that a minimalist moral view could endorse separate moral reasons against engaging in {vice, rights violations, breaking of norms, or uncaring responses}, independent of their effects on conscious experiences. To define the former in terms of the latter would seem to collapse back into welfarism.

Executive summary: The post outlines various moral reasons why plausible minimalist views do not recommend absurd acts like murder or sabotaging healthcare.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.