If it can be done by AI, it probably will be

Cross posted from my Substack.

Introduction

I found myself in a discussion over the holidays with Seb Krier from Google DeepMind about what factors will be most important in determining the effect of powerful AI on the labour market.

I have claimed previously that given sufficiently capable and cheap AGI comparative advantage doesn’t matter very much. That is, however, very much a thought experiment about what matters in the limit. This post will deal in more concrete examples.

To explore this question, I have built a tool for modelling the effects of AI on the labour market. This tool makes some basic assumptions and simplifications about the labour market, and allows the user to play around with expectations about AI capabilities and speed of adoption, compute costs and availability, and economic questions about the amount of induced demand there will be due to greater capabilities, and get estimates of how that would affect human employment in cognitive tasks.[1]

This post will go through the model, some key parameters, and several example scenarios, followed by some tentative conclusions.

Limitations

This is only a very simple model of an economy - in practice there are many types of tasks[2], and interaction terms between AI capabilities and human productivity, uncertainties about what might be possible with AI capable of tasks beyond human abilities, and I’m sure many other issues I make no attempt to address. This is best thought of as an intuition pump rather than a forecasting tool.

The model implicitly assumes something like perfect substitution for human and AI labour within the portion of tasks modelled as achievable for AI. That is, if an AI can do a task for less than a human can, there is no reason to employ a human also[3].

It also doesn’t cover things we might strongly prefer be done by humans. It seems plausible to me that much of the consumer facing fraction of the entertainment industry, for example, might be immune to automation (nobody cares if a robot is better at basketball than LeBron James). My intuition is that such tasks are a small fraction of the economy and will remain so, but this might be incorrect.

It only deals with cognitive labour, not physical labour. It is possible that humans might be displaced into greater demand for physical labour if there are limitations on the capabilities of robotics. This is not my base case (I expect robotics to also develop quickly) but is not addressed by the model.

It also says nothing about AI related extinction risks, or significant societal changes which effect economic considerations, etc. These are all beyond the scope of this tool.

The Model

Labour Substitution

The model is designed to only look at cognitive labour initially. This was for simplification purposes - questions about how much compute will be required for and allocated to robotics and other physical domains seemed too big a complexity to add, since I know very little about them. Extending the model may be feasible for someone who does.

The model splits cognitive labour into 5 task tiers in increasing order of difficulty:

- Routine - routine emails, simple lookups, form filling (25% of labour hours demanded)[4]

- Standard - document summarisation, code review, data analysis (35%)

- Complex - multi-step research, strategic planning (25%)

- Expert - novel research, high-stakes decisions (12%)

- Frontier - breakthrough innovation (3%)

Within each category there are several key parameters:

- Initial σ (∈ [0,1]) - the proportion of tasks at that tier AI can complete at the starting year

- Terminal σ - an upper bound on AI capabilities in that tier

- σ midpoint - the year in which AI capabilities reach halfway from initial σ → terminal σ

- σ steepness - the rate at which capabilities will improve within category. Higher steepness will cause a shorter transition from initial σ → terminal σ [5]

- Deployment lag - a number of years between capabilities being possible and being deployed in the economy within that tier.

- Compute cost per labour hour[6] in 2024 FLOPs[7].

There are also parameters for human wage premiums per task tier, for the proportion of humans capable of doing a given task tier[8], for wage elasticity and task value (an upper bound on wages).

For example, if you think AI can currently do 10% of routine tasks, and expect it to ultimately be able to do 90% of them, you would set initial σ = 0.1, terminal σ = 0.9. The functional form of the trajectory of σ is a sigmoid.

Compute Supply

We take estimates from various sources but primarily Epoch AI for compute trajectory defaults. Key parameters:

- 2024 compute available - defaults to 10^21.7 FLOP/s from Epoch AI estimates.

- Initial YOY compute availability growth - default 100%

- Compute growth slowdown - default 10% (that is, YOY growth will be 10% lower each year, so 100%, 90%, 81% etc by default)

- Algorithmic efficiency gains - default 2x, meaning compute required for a given capabilities level will halve YOY

- Efficiency Gain Slowdown - default 15%, the degree to which efficiency gains will become harder to find over time

Labour Demand

- Cognitive work share - the proportion of global work which is cognitive in nature. Default 40% (from a McKinsey estimate).

- Baseline demand growth - background rate at which demand for cognitive work grows, default 3% annually

- Demand elasticity - how much demand for a certain kind of work increases as costs fall. 0 implies fixed demand, 0.5 implies a 50% increase if costs halve, 1 implies a 100% increase as costs halve. Can be >1.

- New task creation - to allow for new categories of work to exist as capabilities grow. Equal to change in σ from base level multiplied by coefficient (so at 0.5, if AI can do 20% more human tasks, we assume another 10% of new tasks become enabled).[9]

Compute Production Costs

- Current cost per exaflop - default $1.

- Cost decrease YOY - default 30%.

- Cost decrease slowdown - default 5%.

These represent production cost estimates - equilibrium costs can rise higher if demand is sufficient.

Scenarios

Below I will go through some scenarios I set up in the app and their projections.

Default: Most things are ultimately automatable, but it takes time

Key parameters:

- Terminal σ < 1 for complex, expert and frontier task tiers (0.9, 0.9, 0.8), everything else can be fully automated.

- Quick progress: frontier task automation saturated in late 2030s

Some results

:

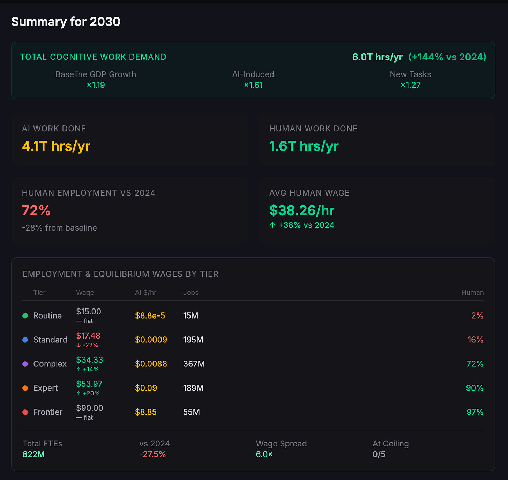

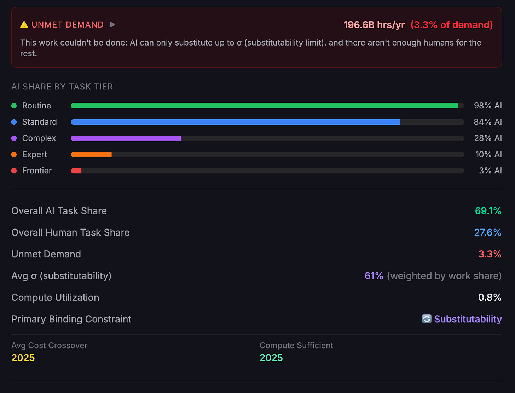

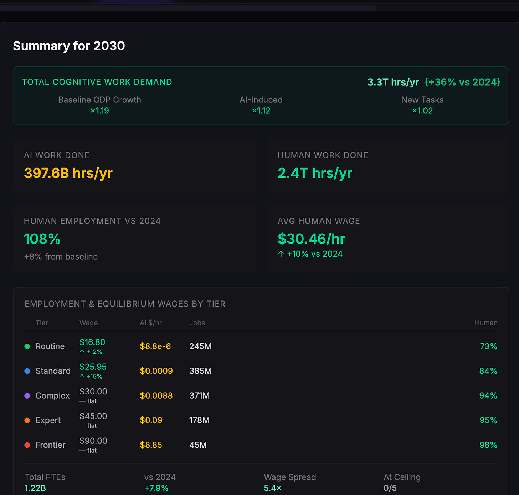

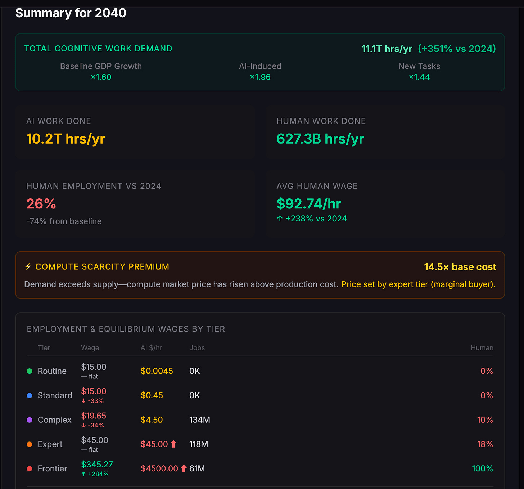

In 2030, there is significant wage pressure on lower tier work, and disemployment (employment is down 28% from baseline). For higher tier tasks wages have actually risen as AI induced demand boosts wages. Total work done has exploded. Compute has not been a limiting factor - if the compute is being used, it is for something else.

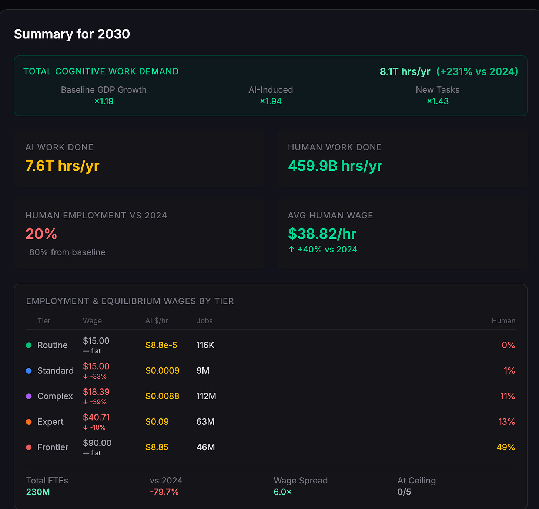

By 2040, humans are no longer competitive for simple tasks, and total work done has jumped by a factor of 4.5, but not enough to induce enough demand to keep wages high for those jobs that humans still have an advantage in.

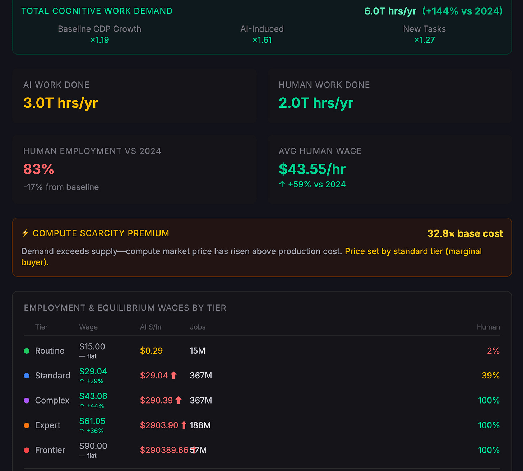

Scenario 1: Slow Progress, AI reaches capabilities ceilings

- Terminal σ < 1 for all task tiers (0.7, 0.6, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3)

- Modest progress: routine tasks mostly not automated until 2030, frontier tasks >2040

Some results:

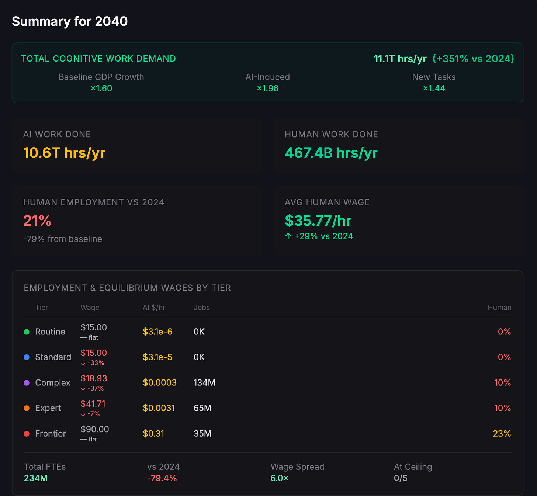

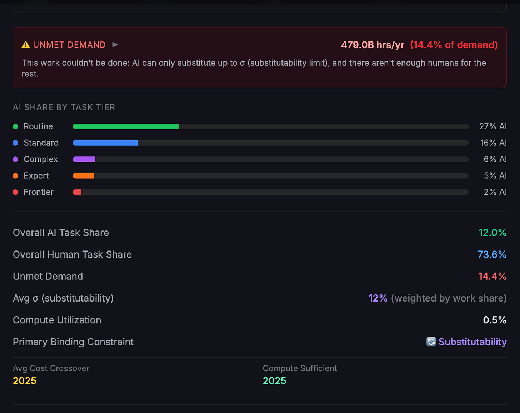

In this scenario, in 2030, AI has had a modest impact on the economy. About 1/7th of labour hours are AI, and human wages for tasks at the bottom rungs have increased, as the overall increase in tasks to do creates more opportunities for individuals[10]. The limit on further work being done is not compute but substitutability - there aren’t enough humans to do all the work that could be done, and AI capabilities aren’t sufficient to do it. There is unmet demand for higher tier work limited by a lack of human workers and the incapability of AIs to do the tasks.

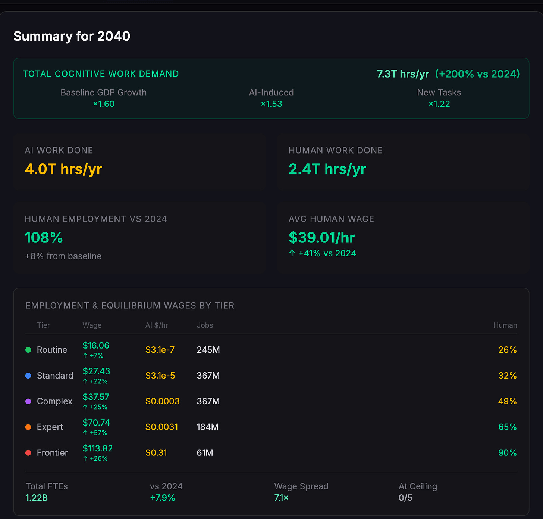

In 2040, changes are much greater. AI is now doing a majority of work, but there is still full employment for humans and wages have continued to rise.

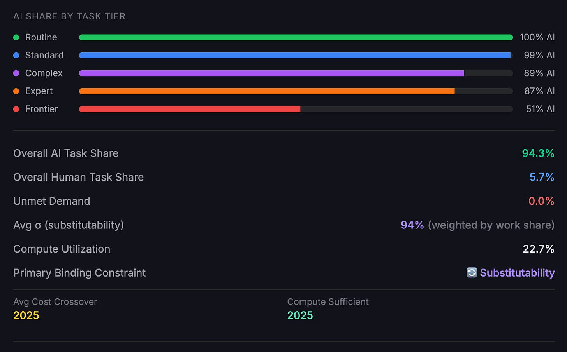

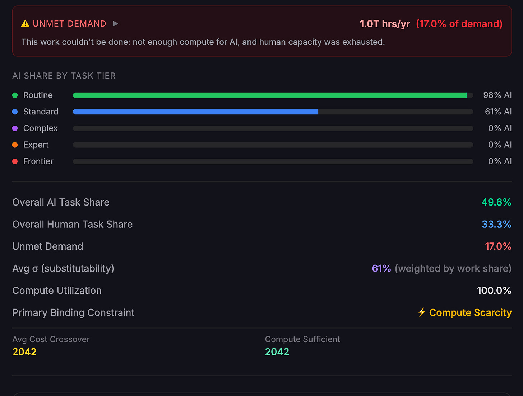

Scenario 2: Fast takeoff, full displacement

- Terminal σ = 1 for all task tiers

- Human ability at frontier tasks saturated in early 2030s

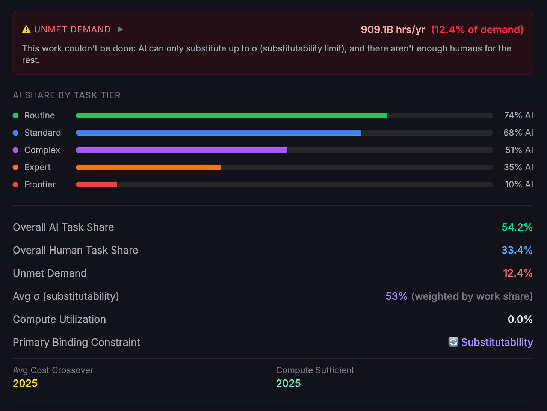

Total work done explodes by 2030, but labour suffers - humans are rapidly displaced. This is the first case where we see cognitive work making a dent in the compute budget, but it is still well below using it all up.

By 2034 there are essentially no human workers left to do anything.

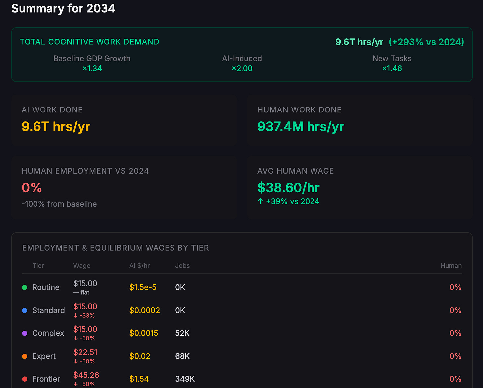

Scenario 3: Compute constraints bite

- All compute costs increased by 3 OOMs

- Compute growth baseline reduced to 50% YOY

In 2030, wages are pushed up dramatically for most labour, but routine work is automated. Compute prices spike above production costs by a factor of 32 (making humans cost competitive at standard tier tasks).

By 2040, human employment is much lower, though frontier tasks are still fully human due to compute costs.[11]

Other scenarios

There are other scenarios in the calculator (see scenarios tab) including modelling much greater induced demand, and a slower timeline which sees no disemployment effects till the late 2030s. Feel free to explore and create your own.

Conclusions

My main takeaways from this are that compute will only be a binding constraint on how much AI gets used to replace human labour to the extent that there exist many extremely valuable tasks which take an enormous amount of compute to carry out.

It does not seem obvious to me that most valuable tasks would take a very clever model huge amounts of compute - while reasoning models like GPT 5.2 Pro and the unreleased models which scored IMO gold medals from OpenAI and Google DeepMind may have used huge amounts of compute by today’s standards, the cost to do any given task has declined rapidly over time, and many human level tasks, especially those things which employ the majority of people with cognitive jobs, seem likely to me to take relatively small amounts of compute, to the extent that they can be done, which should avoid them becoming cost-prohibitive to replace. Displacing such jobs seems much more a matter of capabilities, not compute.

Non-cognitive tasks which might involve robotics face different constraints. I expect they would also not take huge amounts of compute, because to the extent that they are possible running smaller local models will probably be required for latency reasons, and that would bound how much compute they could require. Capability progress here is something I know much less about.

Where, then, must all the compute go? Why are the companies building so much capacity?

Looking at current applications, very little of it is doing things like directly competing with cognitive labour[12]. It is currently primarily an augmentation tool, allowing humans to do more, as capabilities do not allow for full substitution of many individual jobs yet. But the most expensive part of the productive capacity of the economy is the human labour element, and so it seems very plausible to me that as soon as capabilities reach a threshold where this can be cut out, we will see displacement. The majority of the compute can still be used in tooling for the cognitive labourers, whether the cognitive labourers are AI or otherwise.

- ^

Full modelling details and source code can be found on github. Virtually all of the code and readme docs were AI generated, however I have stress tested it extensively and take full responsibility for any errors.

- ^

Seb highlighted that separability of tasks is disputed in the economic literature. The O-ring model in that paper would likely imply much bigger increases in total productivity, and in wages, for those capable of doing the relevant work, than my model implies, and much greater difficulty in replacing humans prior to their jobs being fully automatable, as the residual tasks would dramatically increase in value. However it does not contradict the claim that if AI can do all of the tasks a given job requires, that job would be done by AI labour if it was cheaper than human labour.

- ^

This is similar to claiming negligible complementarity, which was an assumption which Seb disputed. I struggle a little with the distinction here. To me, it is hard to parse “able to do everything and be super cheap” as not being able to do what humans can do for less than humans can, in the absence of compute constraints which must be allocating the compute to things worth more per unit of compute than the human labour replacement costs.

- ^

Note that these descriptions and examples are not particularly load bearing here - it is enough to say that some things will be easier than others to automate with AI, and cost less compute on average. You can even tweak the parameters such that some things are easier but more compute intensive, and some things are harder but require less compute, if you so wish.

In particular the frontier and expert numbers are likely too high for an estimate of labour share for true expertise or frontier research, however, if we primarily care about population unemployment levels it makes sense to look at categories which are a meaningful proportion of the total.

- ^

Assuming fixed σ midpoint, higher steepness also implies a later starting date for changes to σ (since it will take less time to get from initial → midpoint).

- ^

This is one of the hardest parameters to reason about. Some intuition pumps: human brain estimates are on the order of 10^21 FLOPs/hr, while frontier LLMs are estimated to be on the order of 1017-1018 FLOPs per million tokens, depending on the number of active parameters. The default parameters have routine work taking on the order of 100k tokens/human labour hour, standard work 1m tokens/hour, complex work 10m, expert work 100m, and frontier work 10bn. I mostly pulled these out of thin air and intuition. I have a documented scenario stress testing increasing these by 3 orders of magnitude.

- ^

Since we separately model algorithmic efficiency gains, the actual number of FLOPs used will decrease over time.

- ^

Workers have skill ceilings - only 5% of workers are modelled as capable of frontier work, 20% of expert work, etc.

- ^

This is different to induced demand because the mechanism is capabilities rather than costs.

- ^

I assume some fraction of individuals who start off working at each tier are capable of higher tier work, and so the creation of more Routine work output creates more Standard jobs, and this echoes up the task tree. See the full model for more detail.

- ^

That frontier tasks would be the last to automate is just a consequence of their outsized compute costs in the model here and the bounded task value - if the economic surplus from doing them was sufficiently high (e.g. the tasks have enormous value) we would expect AI to substitute more. I encourage playing around with the model.

- ^

The main example where it plausibly is, code generation, is still at the “maybe it is displacing humans” stage, rather than it obviously doing so.