For some of us, experiencing the world has always been intense. From a young age we’ve known that there’s a lot more to reality than most people seem to be aware of – patterns, subtle details, a bigger picture that escapes notice. Emotions, whether they’re held by others or ourselves, are powerful to the point of being occasionally incapacitating. Art, films, music, novels, and poetry are profoundly moving. Sights, sounds, and textures are captivating, yet we often find that we need more time to rest and recover after a particularly draining period of exposure to stimulating environments like parties or conferences. Our ability to read intentions is exceptional and people are often stunned at how we’re able to complete their thoughts and judge the character of strangers.

To others this natural sensitivity seems odd. We tend to be disturbed by seemingly small changes made to our routine or workplace, and direct conflict presents an enormous affective challenge, especially when it’s with people we care about. Preoccupation with idealistic causes or niche interests is baffling to anyone pulled along by the standard impulses in a noisy and distracted society. In a group of friends we’re typically the quiet one, although when it comes to describing what we’re enthusiastic about the sudden energy can seem out of character. At work or in school finding a spot in the corner to carefully apply our skills is more appealing than being the centre of attention.

Our curiosity and creativity aren’t usually appreciated, but when they are our hearts soar. Positive feedback from a boss or a compliment on a tastefully assembled outfit can transform a bad day in seconds. The rare occasions offering an opportunity for high quality connection are a gift from above as at last we’ve found someone else on the same wavelength. Falling in love is an all or nothing process, more powerful than any song or romcom can capture. Rejection, whether it’s personal or professional, cuts deeply and can lead to cratered self-worth. When we do find a person that understands our idiosyncrasies we latch on for dear life as it might be a long time before another emerges, if ever. Family, acquaintances, and coworkers often count on us to lend a listening ear, but we need their support more than we’re willing to admit, and when it’s sincerely offered it can make a crisis shrink from galactic to merely mountainous.

Through a painful but ultimately rewarding process, I’ve discovered that the above is all linked to a personality characteristic that the EA community will greatly benefit from learning about. This trait, or more accurately super-trait, is what psychologists and neuroscientists call high sensory processing sensitivity or to use author Elaine Aron’s term the Highly Sensitive Person (HSP). There’s been ample discussion of mental health and wellbeing on the forum, but thus far this concept has escaped notice, which is a loss for the movement as many people who are dedicated to doing good better probably qualify as having high sensitivity without knowing it. As described below, being an HSP has a unique set of advantages and drawbacks, which make understanding this super-trait highly actionable for increasing personal efficacy and avoiding the perennial and under-reported problem of burnout.

What is SPS?

Sensory processing sensitivity is a measure of how strongly an individual’s nervous system responds to environmental stimulus. This is separable into two components: input and processing.

For the first, the framing of higher information density is helpful: each block of sense data received by the brain’s perceptive organs per unit time has much more packed into it. Sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touch, and thoughts and emotions (which can be considered a composite sixth sense from the basic five) are richer and fuller. The highs are higher and the lows are lower. For the technically inclined, greater variance comes to mind.

With increased density comes the cost of taking longer to process and integrate the torrent of sensory information. The exact mechanisms for this are unknown, but a working hypothesis is that both the default mode network and the salience networks are involved: the former enables internal narrative and the latter directs attention towards specific stimuli. We can imagine that the stream of sense data flows more slowly through the brain since it’s ‘thicker’, and naturally a denser fluid moving through a same sized channel will take longer.

Critically, this doesn’t imply being easily overloaded by sensory information as the term might suggest, although this is a common situation. Rather, HSPs experience all stimuli more intensely, and individual tolerances vary. Depending on genetic and other factors one person might have a much lower threshold for emotions or sounds while another has a higher setpoint before short circuiting. It’s possible for someone with high SPS to be risk-seeking relative to the general population since they’ve discovered from experience that certain kinds of positive stimulus are enjoyable to the extent that the intensity more than makes up for the possible losses (e.g. extreme sports, stock market trading). By the same token HSPs can also be extroverted: studies on the distribution of Big Five personality traits among this population show weak positive correlation with introversion, making the stereotype of a shy, socially withdrawn wallflower one of many possible temperaments.

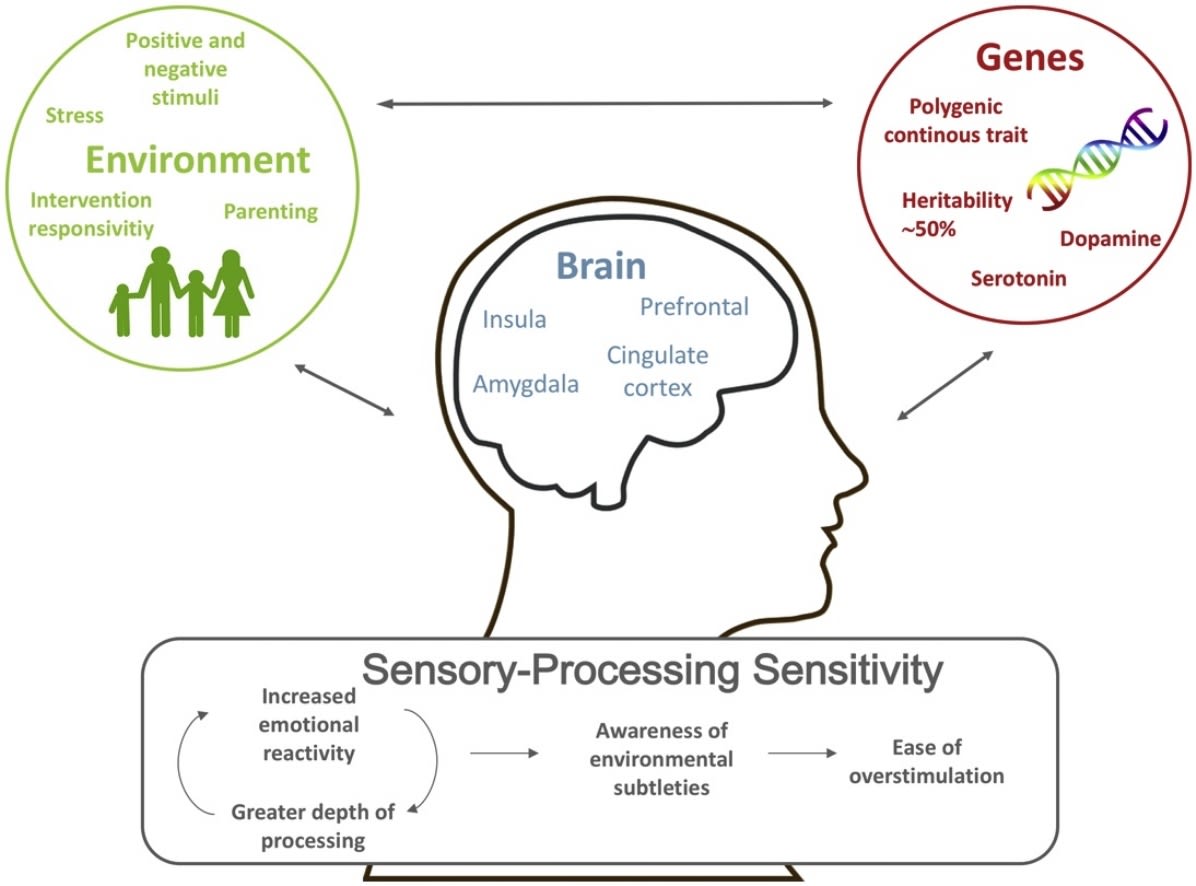

The following image illustrates how genetic and environmental influences interact with the highly sensitive brain:

Fig. 1, Greven et al., 2019

The primary gene involved is the short version of the serotonin transporter SERT or 5-HTTP, which is about 50% heritable and controls serotonin production. In contrast to the long version, which is associated with emotional stability, the shorter variant codes for increased emotional reactivity. When it was first discovered in the 1990s a slew of papers was published on the possible link between carrying it and increased risk of depression. Study results were mixed and the connection was forgotten until researchers rediscovered it two decades later and came to a different conclusion: rather than susceptibility to negative emotion, short SERT enables greater emotional response in general. The polarity of emotional experiences is augmented at both ends and with the right conditions the positive component can be magnified.

Short SERT has since been renamed as a plasticity gene due to its effect on how a carrier responds to their environment. In a challenging environment they have increased difficulty surviving, whereas in a supportive environment they thrive, often to an astounding degree. A picture comes to mind of the reserved high schooler suddenly blossoming after joining a club related to their interest and joyfully realizing that they don’t have to hide who they are anymore. Early childhood experiences seem to play an especially important role: during this critical developmental period the attention of a caring parent or teacher can make the difference between flourishing and withering. Overall the result is amplification of whichever environmental influences are present, positive or negative. With social support individual carriers are more likely to recover quickly from stressful events and suffer more without it.

Other genes contributing to HSPS include MAOA, DRD2, and DRD4, which are involved in the release of dopamine in the brain’s reward system. This connection is less well established but it’s thought that increased sensitivity to reward leads to higher curiosity and creativity – traits held by the sensitive artist or intellectual. The research also shows a positive relationship with HSPS and the personality trait of openness to experience, i.e. greater appreciation of aesthetic, philosophical, entrepreneurial, and scientific pursuits.

~25% of the human population falls under the HSP classification (estimates range from a third to a fifth, so I’ll stick with the median) and a similar fraction seems reasonable for other mammalian species. Why would such an attribute have been selected for by evolution, given how energetically costly it can be to an individual organism? The reason is that for a subset of the population increased sensitivity results in adaptive flexibility: when confronted with a novel situation they are more able to respond in a fitness-promoting way. For example, one of our hominid ancestors might have noticed a new kind of edible root or berry while foraging or invented a tool while playing with sticks and rocks. This adaptability counteracts the drawbacks of vulnerability to overstimulation in high stakes situations such as confronting a predator or mating rival. Over time positive feedback supports a stable level of sensitivity, as the benefits of responsiveness are carried forward to the next generation through natural and sexual selection.

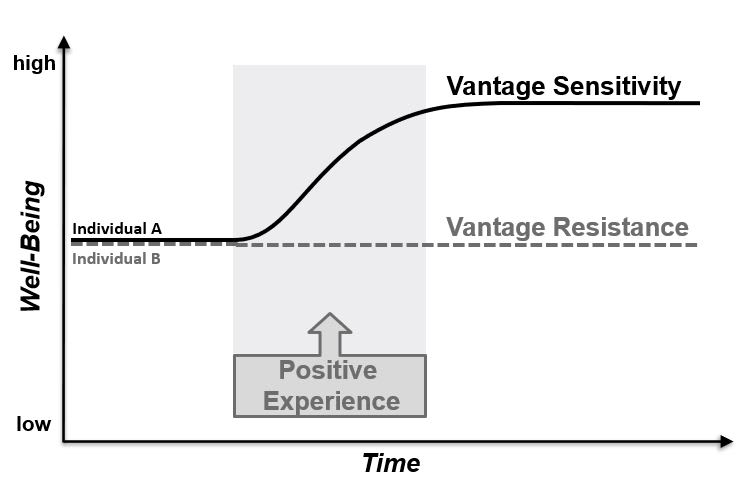

Fig.2, Pluess & Belsky, 2013

Another descriptor for the interaction between environment and genetics in the case of this subset of the population is that of vantage sensitivity. From an evolutionary perspective these individuals have a much finer-grained instinct for their position in the fitness landscape and are thus more able to pivot in a fruitful direction under the right conditions. When exposed to positive experiences, such as supportive relationships, tailored therapeutic interventions, and opportunities to develop their talents, they benefit particularly strongly. Things that anyone would find helpful are boosted – mentorship from a respected colleague or a friend’s encouragement dissolve crippling self-doubt and amplify joie de vivre. In the span of a few months, someone who previously stood on the sidelines can undergo a radical transformation into an active participant in meaning-making, a creator with a glint in their eye and zest for life. As well-being improves the effects are felt by people around them as their natural disposition yields energy, connectivity, and generativity.

Characteristics of HSPS

Researchers have identified three aspects of high sensitivity: low sensory threshold (LST), ease of excitation (EOE), and aesthetic sensitivity (AES).

- LST

The classic marker. Individuals high in this aspect find sensations of all kinds more intense, making them super sensors. They are highly attuned to their environments but easily become overstimulated.

- Energized but rapidly tired by crowded or busy places

- Strongly affected by alcohol, caffeine, medication, drugs in general

- Disturbed by loud noises, bright lights, and uncomfortable textures

- Enjoy ASMR type experiences such as whispering or hairstyling

- Immediately notice changes in temperature

2. EOE

Response to emotional stimuli. Whether they’re felt by oneself or others, emotions pack a greater punch. Super feelers are also skilled at reading other’s intentions.

- Easily absorb emotions and feel them more intensely

- Need more downtime after affecting experiences, especially arguments

- Fear of rejection, strong negative reaction to making mistakes

- Feel extremely tense when doing tasks under time pressure

- Become hangry (hungry + angry) or hanxious easily

- Very low or very high pain tolerance

- High startle reflex

3. AES

Sensitivity to beauty in all its forms. Super appreciators pay close attention to details and are more likely to experience a sense of awe and wonder.

- Deeply moved by music, cinema, plays, art, novels, poetry

- Refined taste for complex scents, colours, sounds (e.g. gourmet food, perfume)

- Notice when something is slightly off in a report, presentation, model, etc.

- Strong intuition for improving an unwelcoming environment (furniture, light, decorations)

- Need for harmony, symmetry, consonance

- Savour time spent in nature

- Rich inner world

HSPs score highly in evaluations for at least one of the above aspects but any combination of the three is possible, for instance higher AES and EOE with lower LST (the combination that applies in my case).

Advantages

In their excellent book Sensitive which I’ve drawn from heavily to write this post, Jenn Granneman & Andre Sólo outline five ways that HSPs can leverage their disposition to benefit themselves and others.

- Empathy

Mirror neurons are a type of brain cell suspected to be involved in theory of mind, i.e. understanding and predicting the internal mental state of another. They’ve been shown to fire both when an organism performs an action and when a different organism performs that same action (hence the ‘mirroring’). Several neuroscientists have argued that these neural circuits also underpin the human capacity for empathy, with imaging studies showing that brain regions including the insula and anterior cingulate cortex light up when an individual experiences an emotion and when they witness another person having an emotional experience.

Germane to HSPS, individuals self-reported as higher in empathy showed much stronger activations in the mirror neuron system for emotions. They were not only more skilled at identifying diverse emotional states but also experienced greater activation in brain regions associated with action planning, indicating desire and intention to help others in distress. This effect was demonstrated in the case of strangers experiencing fear and pain and is thought to be involved in acts of heroism such as diving into deep water to save someone from drowning.

HSPs are uniquely positioned to understand what another person is experiencing, which is beneficial for both selfish and prosocial reasons. In competitive environments such as large corporations being able to read the intentions of others and anticipate their actions is useful for climbing the ladder – it’s easier to get promoted or avoid the cull of a restructuring when you’ve suspected for weeks that management is about to make a high-stakes decision. More importantly, this ability allows for a sympathetic response when someone else is going through a difficult time. HSPs find themselves easily able to gain the trust of others due to their listening skills and interpersonal warmth and are often the friend or coworker to turn to for moral support when things go awry. They also feel drawn to caring professions like teaching, healthcare, clergy, and international development.

2. Creativity

Not all HSPs pursue creative vocations, but it’s estimated that a higher fraction of creatives are sensitive relative to the base rate. This is intuitive as noticing more details and having a finely tuned aesthetic and emotional barometer facilitates making new connections and generating novel insights. A 2009 study by Nina Volf and collaborators showed that carriers of the short SERT variant scored significantly higher on measures of verbal and visual creativity than controls.

Theories on the origin of creativity are as diverse as the arts, but there’s a common theme of bringing together seemingly disparate ideas to yield something new and interesting. One of the first developed, divergent thinking, describes the loose and nonlinear process of freeflowing idea generation where evaluating ‘correctness’ is less important than spontaneous exploration. Conceptual blending is another where the apparent boundaries between separate domains are dissolved to allow for mixing and recombining. Positive emotions also play an important role, as in the broaden-and-build model where cultivating well-being leads to curiosity, inventiveness, and playfulness.

Exhibiting high sensitivity primes individuals to be creators as they’re constantly absorbing the vibe of their environment. After travelling, dabbling, and experimenting with career paths, inhabiting multiple perspectives naturally germinates strange and beautiful new worlds that seem unorthodox or even orthogonal to the consensus. Frank Herbert held the occupations of journalist, photographer, and jungle survival instructor before starting his masterwork.

3. Depth of processing

In the levels of processing model developed by cognitive scientists Craik and Lockhart in 1972, mental processes occur across a continuum with two regions: shallow and deep. Shallow processing occurs at the perceptual level, i.e. immediately perceiving the stimulus, and produces memory traces that evaporate after a few seconds. Deep processing occurs at the semantic level, where the meaning of the stimulus in relation to the hierarchical network of concepts, images, associations, and experiences stored in long-term memory is determined. Accessing this mode of operation has a longer warmup and cooldown period for the brain and is more susceptible to noise (which is why a quiet environment is necessary for deep work) but catalyzes connecting more details that are missed in the faster shallow level.

Many advantages arise from swimming in the deep end including creativity, focusing for extended periods of time, and a distaste for any sort of surface-level activity. Critically for the target audience of this post, deeper processing enables better decision-making. Drawing on more information sources allows for higher quality decisions when trying to orient one’s life in a meaningful direction such as finding a vocation that improves the world in a carefully considered way.

Sensitivity of this kind is particularly beneficial in high-stakes situations since a moment of pausing to check before following an impulse can make the difference between saving a life with the right medical treatment or inadvertently ending it. More accurate perception of risk dovetails with vantage sensitivity, as an organism’s hyper awareness of its place in the pecking order prevents it from moving in a direction exposing it to physical or social damage. Akin to military strategy it’s necessary to consider all possible angles of attack before committing the platoon to a maneuver, maximizing the chances of victory while minimizing losses. This instinct to wait can seem like hesitant idling to less patient folk although when harnessed in a suitable way it can be immensely valuable, whether in the context of work, relationships, or leisure. Over time lived experience in a specific domain produces an ability for correctly predicting outcomes that to a layperson seems downright magical.

Feeling the market in finance is one version of this phenomenon. The best options traders and hedge fund managers seem to possess an uncanny knack for predicting where prices are about to move and adjusting their positions accordingly. They’re also able to detect subtle underlying patterns that are faint signals of hidden dynamics, indicators of tectonic shifts in the investment landscape. As depicted in the 2015 film The Big Short, a small group of outsiders acted on the hunch that mortgage-backed securities had hidden risks unseen by most investors and made billions during the ensuing financial crisis.

4. Sensory intelligence

The sensorium of a HSP is more abundant in its structure and contents than that of a member of the less sensile majority. Heightened awareness of everything in one’s perceptual field is comparable to a radar antenna that is more responsive to changes in the electromagnetic spectrum, or a web-slinging New Yorker superhero’s signature sixth sense. Variations in the environment that would usually go unnoticed are constantly being picked up, which combined with domain knowledge can be extraordinarily useful.

In the context of professional sports, finely tuned perception of the action at a point in the game is called field vision. This ability allows a skilled player to maintain a mental map of their and the opposing team’s moving positions and anticipate the best next place to maneuver. Wayne Gretzky, nicknamed The Great One for his still undefeated scoring records in hockey, instinctively knew where his teammates were moving on the ice and as a result was able to make game-changing passes in the blink of an eye. An exemplar from le foot is Zinedine Zidane, renowned for his elegant ball control and performance as a playmaker. While not being an outstanding goalscorer, he leveraged his positional sense and spatial awareness to benefit his team as a whole, whether it was a private club or in international appearances as part of the French escadrille.

In high-risk professions such as emergency medicine situational awareness can be a matter of life and death. A perceptive paramedic might notice an overlooked detail (say skin discolouration) and swiftly decide to transport the patient to the proper hospital department before the condition reaches the point of no return. An experienced firefighter, recalling an element of architectural design seen in a museum exhibit, is able to contain a blaze through skillful redirection of oxygen flow.

All human activities have a perceptual aspect, so it’s not necessary to be in a fast and furious situation benefit from sensory intelligence. A simple gesture such as complimenting a prospective employer’s or romantic interest’s fashion choice can add chroma to an otherwise lackluster interaction. Observing drops of rain sliding down a window or breathing in the exquisite scent of a fresh magnolia blossom transform a dull morning commute into an opportunity for deep appreciation. Regardless of the outcome, savouring the vividness of the world adds flavour to mental palates diminished by digital distraction.

5. Depth of emotion

Affective tsunamis seem reserved for artists, musicians, and actors, yet HSPs as a whole are blessed or perhaps cursed with the capacity for profound emotional experiences. In some contexts this appears to be a disadvantage, but the broader palette of emotion available grants a more vibrantly hued view of the world. Seeing gradients of colour where others perceive plainness is a gift that is generative given the proper conditions.

The primary brain region thought to be involved in emotional processing is the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). Located deep within the frontal lobe, it connects to many other neural structures and functions as a relay point where information from different sources is amalgamated. Crucially, it provides both input and output to the amygdala, an older part of the brain associated with emotions, learning, and memory. Popular science tends to focus on the amygdala’s involvement with fear and aggression but it plays other roles including interpreting sense data and social signals. This two-way connection is relevant to HSPS since heightened vmPFC activity has been shown to decrease activation of the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response) and increase parasympathetic activity (rest-and-digest).

More sensitive individuals also exhibit greater emotional intelligence. A more densely connected vmPFC enables richer integration of emotions with other forms of data, which provides a broader emotional palette and more vivid affecting experiences. Emotions are necessary for long-term memory formation – the stronger the association between a concept and a feeling, the more likely you are to remember it. HSPs absorb more emotionally relevant content from all situations and their nervous systems encode it to a greater degree, facilitating faster recall and idea linkage. Doing so is particularly helpful for understanding other’s perspectives and persuading them to adopt a different view. A quality relationship is a much better starting point for changing someone’s mind than shoving ideas down their throat, a fact known by salespeople for centuries.

Being ‘overexcitable’ is often interpreted as a reason for embarrassment, but experiencing joy and sadness more fervently allows the HSP to be driven by a relentless impulse to connect to something greater than herself. Emotional intensity fosters greater self-awareness in such a way that one’s unique perspective and disposition are resources aimable at a higher purpose. With effort this idealism can be transmuted into grounded passion that interfaces with reality rather than gyrating in the Platonic realm. Social reformers convince wider society to change the status quo in a humanistic direction due to how compelling their visions are, as demonstrated by a vegetarian Australian philosopher.

Disadvantages

The above qualities also have significant drawbacks, reifying the adage that every rose has its thorn.

- Emotional contagion

A critical distinction to draw that EA forum readers are already familiar with is the difference between empathy and compassion. The former involves identifying and experiencing other’s emotions, whereas the latter is cultivating a desire to be helpful and taking action on that basis. Getting caught up in someone else’s suffering doesn’t mean that you’re in a good position to relieve their pain– in many situations it’s the opposite. HSPs are particularly vulnerable to being pulled in by emotional whirlpools and spinning around to the point of dysfunction, whether it’s by exposure to high conflict people or reading pessimistic news stories. When combined with a quantitative outlook this can easily lead to analysis paralysis, as the impossibility of finding a globally ‘correct’ answer to the problem of moral luck creates cycles of panic and giving up, culminating in a downward spiral.

Crucially, empathy involves an inward focus on our own feelings, whereas compassion has an outward orientation: genuine desire to connect with and support another person who is suffering. Negative emotions tend to be produced in the first which promote inflammatory effects, while the second is associated with positive emotions along with decreased heart rate, calm, and the stress-relieving hormone oxytocin. Avoidance is at the root of the former and approach the latter.

Encouragingly, compassion is learnable – we all have the capacity to care for others thanks to millennia of social bonding in tight-knit small groups. In the modern environment it’s diminished by urban anomie and overreliance on information technology but can be rekindled with effort. Small actions to start with include making a small donation to a personally meaningful cause (even if it’s suboptimal in terms of cost-effectiveness), asking someone who’s visibly struggling how they’re doing, sending a friendly message to a friend or relative going through a difficult time, and giving yourself time to recharge after a draining day or week. With practice doing so shifts from an uncomfortable risk to an automatic and naturally rewarding habit.

2. Boredom

The downside to creativity is a strong aversion to routine, predictable occupations, and any form of rigid social structure. Fixed schedules with monotonous tasks can feel oppressive while working with overly orderly people leads to a clash of wills. The statement ‘this is how we’ve always done it’ seems absurd to someone versed in bending the rules, which are arbitrary human constructions instead of universal laws. In a hierarchical setting this kind of questioning is easily interpreted as a threat to authority and should be done tactfully such that the benefits of doing so are well communicated.

Associative memory often activates in a spontaneous fashion which non-creatives can view as unfocused daydreaming. In a competitive environment where the priority lies in winning according to some gameable metric, not jumping around in a state of agitation seems threatening to the status quo. Even in companies claiming to be pro-innovation the type approved by management can be restricted to a certain range of marketable ideas – a far cry from unencumbered creation. Constraints can enable great art, as demonstrated by many artists who restrict themselves to a particular medium in the course of a project, but when externally imposed they’re binding without being bountiful.

Next to that problem is the conundrum of vulnerability. Some of our brightest moments come from opening ourselves up to others, especially when we’ve made something unique, yet this can only happen with exposure to terrifying rejection. When, where, to who, and how much to show are vexing concerns that never resolve with thinking alone. Learning the rhythm for sharing our creations is a trial and error process so it’s best to start small with a trusted person and work your way up to higher stakes.

3. Unproductive immersion

After discovering a tantalizing idea there’s a tendency dive deeper and deeper, hoping to find the final answer at the hadal bedrock. Given the nature of the Internet and information technology in general this is futile: no matter how much reading or podcast listening you do the endpoint is never reached. The problem is difficult enough as it is for the curious HSP, made more challenging by how seductive memeplexes have become in our chaotic and unpredictable times, as many seem to offer a neatly packaged solution to the trials of modern life (including this very forum). So what to do?

Web browser extensions, task lists, tomato timers, and the like can be helpful, no matter how sophisticated the productivity system it’s no use if again and again you’re seduced by the latest fascinating tidbit on reddit, Yahoo Finance, or your informational vice of choice. The root cause is always the quality of one’s attention. One way to realize this is creating a spreadsheet and recording the time of day and source of each instantiation of distraction, then comparing it to a calendar where every day of a year is printed on a single page. Regardless of how often you’re able to update it, the act of doing so will change the framing of how the four thousand weeks of a lifespan are being spent. Temporal arithmetic can be shocking at first but the emotional cost is worth paying.

At a more fundamental level the most effective method human beings have developed thus far for training the capacity to pay attention is meditation practice. That’s a vast topic of its own which hundreds of books have been written starting with the Upanishads 3000 years ago, but it suffices to say that for historical reasons Buddhism happens to be the religious tradition with the most systematic treatment of mindfulness. A large and growing body of contemplative neuroscience shows that there’s a dose-response relationship between accumulated hours of meditation practice and beneficial changes in brain structure. Examples include greater connection between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, critical for more adaptive responses to the fight-or-flight reflex, and increased grey matter density, which boosts executive function, i.e. decision-making. Even 10 minutes of practice every other day makes a large difference and it’s not necessary to go on month-long retreats to start experiencing benefits. What matters is consistency that adds up over time.

That’s not to say that the philosophical and ethical underpinnings of Eastern traditions have no value. Many teachers trained by Asian masters have criticized the drift towards ‘McMindfulness’ in the West where the practice is yet another productivity technique rather than a way to radically change one’s relationship with conscious experience. I’ll leave that for the curious reader to investigate, but for the purposes of this post it’s enough to note that there’s far more to meditation than mere stress relief should you be interested.

4. Sensory overload

Like most things in life, a fuller sensorium is a gift that comes with costs. A deep-processing nervous system is always on, even during sleep, and constantly consumes energy – it’s estimated that the brain accounts for 20% of an average adult’s daily caloric intake, and the fraction is almost surely higher for HSPs. The increased density and intensity of sensory input results in a tradeoff with much more time needed for recovery as the nervous system needs a calm environment to dissipate accumulated stress.

A useful analogy is a bucket that fills up over the course of a day with sense data. Every sight, sound, taste, smell, touch, thought, and emotion adds water, and after a certain point it can’t be filled any more and begins to overflow. Some people’s buckets have less capacity and reach maximum capacity sooner. When this happens, the nervous system’s natural reaction is to shut down to protect itself from any further exposure. Overstimulation is experienced in different ways but the common denominator is a sudden drop in energy along with a strong feeling of irritation or anxious tension. This often leads to withdrawing from a situation or activity, which can seem irregular but is necessary for maintaining equilibrium.

Clinical psychologist Paul Gilbert has developed a threefold model of the central nervous system’s operating modes: Threat, Drive, and Soothe. Threat mode stimulates behaviour to increase the organism’s odds of survival and is associated with the fight-or-flight response. The sympathetic nervous system, a division of the CNS, activates the body to move by releasing adrenaline and rapidly increasing blood flow to the heart, lungs, and muscles to prepare for a perceived attack. For evolutionary reasons threat mode is constantly scanning the environment and has a high false positive rate; better safe than sorry. A key contributor to overstimulation is overreach of this subsystem: small disturbances are exaggerated as hostile behaviour before the thinking prefrontal cortex has a chance to reason.

In contrast, Drive mode compels the organism to engage in reward-seeking behaviour. Actions that promote genetic transmission such as social activity, eating tasty food, or mate-seeking are positively reinforced. The parasympathetic nervous system releases testosterone and dopamine for feeding and breeding. Notably, this can’t happen if the sympathetic nervous system has been activated as the impulse to survive overrides everything else. This is where Soothe mode comes in: after a stressful episode the body needs time to recover from the exertion of being on high alert. Resting and digesting can take place as the parasympathetic nervous system is again involved, this time producing oxytocin and serotonin, which are associated with feelings of calm, comfort, and care.

Modern life overemphasizes being in Drive and Threat modes which not only leads to chronic dissatisfaction but can be uniquely exhausting for a HSP. A key strategy for mitigating overstimulation is learning how to activate Soothe mode, which is elaborated on next.

5. Overexcitation

Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems need less input to be triggered for a person with HSPS, making positive feedback a double-edged sword. Higher reward sensitivity creates the possibility for virtuous cycles where taking an action that achieves a result related to a valued goal is energizing, leading to more action, then additional energy. The mirror image of stress amplifying itself is less pleasant: a mistake or bout of bad luck rapidly accelerates into a negative spiral that obliterates any enthusiasm and causes a collapse in morale lasting weeks, months, or years. The addictive nature of how information is filtered through modern media worsens this problem, creating a sense of whiplash when vicious cycles alternate with their exciting twins at high frequency.

In either scenario knowing when and how to activate the escape valve is helpful since the dynamics of a positive feedback loop tend to be punishing. The first step is noticing, which can be surprisingly difficult as the mechanics of subjectivity that generate overexcitation are often subtle. A dedicated meditation practice is useful but not necessary as it’s attainable with a few hours of concentration to notice when the mind begins spinning itself up. The most important thing to observe is how the body changes in response to jarring emotions given the deep connection between the two. Physical symptoms include increased heart rate, flushing blood vessels, muscle tension, headache, tightness in the chest, stomach pain, and restlessness. Noticing when several of these occur in reaction to a captivating thought pattern or stimulus can take a little while to learn but can be done anytime, anywhere – the perfect hobby!

Once the start of a spiral has been detected the next move is to start smoothing out the oscillations. Overstimulation and overexcitation tend to occur simultaneously so focusing on the sensory aspect is simpler to start with and forms the basis for MBSR (mindfulness based stress reduction) and other methods. Independent of what’s happening it’s possible to give yourself calming sensory input, which interrupts the sympathetic nervous system’s Threat mode which at its core is a biophysical reaction to an external stressor. The sense of touch is exceptionally effective at defusing into Soothe mode: a smooth texture such as an item of clothing or wooden surface, a plant, or even a polished stone tile works wonders. Proprioceptive input, i.e. moving the body against resistance, is involved given its association with comfort, which is why weighted blankets and hugs feel so good. Sounds and scents are also superb: green noise or a flowery scent bring sweet relief.

The phenomenon of rapid energizing from sky-high expectations followed by a crash is notable, particularly for those scoring highly on EOE (ease of excitation). Again there’s no one neat trick that functions as a universal solvent for the mind’s tendency to amplify emotions, so experimenting is the only way to discover what works. The key is developing the ability to de-identify from thoughts before they accelerate into an affective spiral. This activates the cognitive brain, popularized as the conscious, deliberative, logical set of processes by Daniel Kahneman in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow, in contrast to the intuitive, emotional, unconscious System 2. A combination of awareness training and meta-cognitive reasoning has been shown to be more effective than the ‘gold standard’ of CBT through meta-analyses of third-wave methods including dialectical behavioural therapy, internal family systems, and acceptance and commitment therapy. Exploring a working relationship with a therapist can be helpful depending on the extent of one’s personal problems although there are plenty of well written books to start with.

Concrete Actions

After learning about HSPS, a potent mélange of emotions might emerge. A crystallization of understanding coupled with solace happened for me as the pieces of the puzzle fell into place and at last an explanation for the variegated troubles I’ve been experiencing since childhood was found. Elation next: the prospect of living more freely. Anger might follow, or sadness at how underappreciated our disposition has been and how poorly we might have been treated for not fitting into the standard model of human behaviour. In the Anglosphere sensitivity almost always has a negative connotation which prevents thousands from flourishing. Finally, a taste of bittersweetness; better late than never to learn.

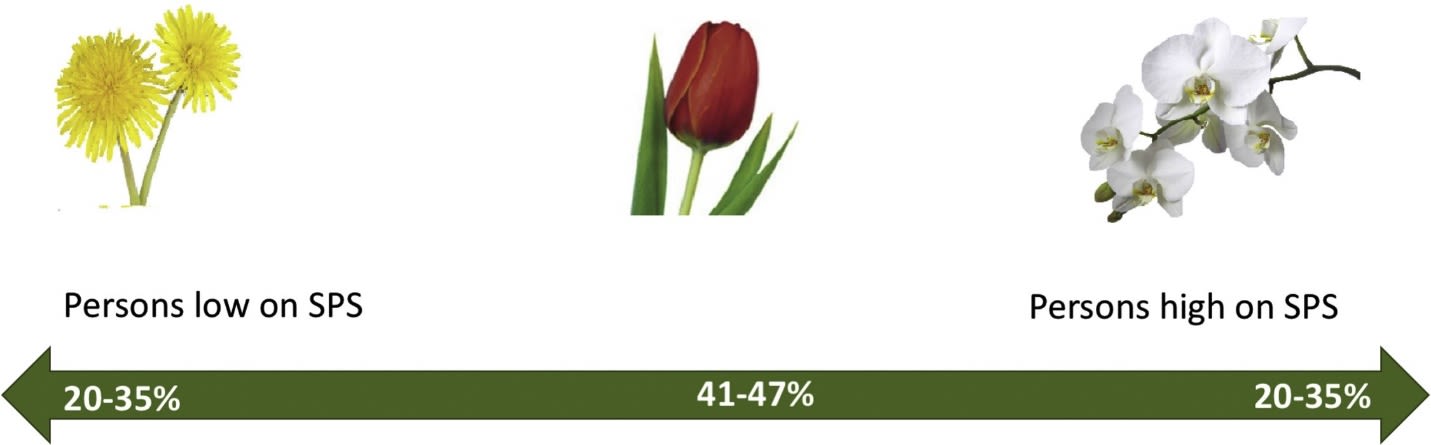

Of particular relevance to HSPs is what’s been called by researchers the dandelion-tulip-orchid continuum. Rather than being a discrete category where a person fits neatly into one of several boxes, sensory processing sensitivity is a continuous trait that captures a large amount of variation. The least sensitive are modelled as dandelions due to how they can grow in nearly any environment but produce unremarkable flowers, while the most sensitive resemble orchids given their need for peculiar soil and watering that with proper care yield spectacular blooms. Tulips fall in the middle and form the largest group, approximating a Gaussian distribution or bell curve as do other characteristics like height and weight. We all have nervous systems that for evolutionary reasons are more or less responsive to stimulus and there’s no single one that’s the global best – each type does better in a specific setting and what matters is finding a fitting environment.

Fig. 3, Lionetti et al., 2018

Identifying where self and others lie on this spectrum is the first skill to develop, as quickly gauging how sensitive people are is useful for establishing what will make your relationships harmonious. Regrettably, an attitude of dislike and even outright hostility may have been developed towards LSPs by HSPs owing to the former’s coarse and inconsiderate tendencies, but this is unnecessary and leads to interactions with increased friction. As with most relational problems lack of understanding is the primary cause which is solvable.

There are many strategies to turn high sensitivity from a liability to an asset, but this post is already egregiously long, so here’s a handy list of seven.

- Modify your environment

No matter where you are or what you’re doing, it’s always possible to make changes to your space in such a way that it’s calming and aesthetically pleasing. Small touches such as treasured photos, decorations with soothing colours, and greenery add joy to drab environs. In the typical open office reserving a specific seat to do this might be frowned upon so in that case emphasize that you’re making the work area more friendly for everyone’s benefit (wellbeing and productivity are tightly correlated).

It's especially important to have a sanctuary to retreat to in moments of overstimulation. Many sensitive people naturally design their living space such that they have a place with physical comfort where decompressing happens, typically stocked with items like candles, soft lighting, plush cushions, and art. After a stressful episode having somewhere to let your nervous system evaporate the tension that builds up over the course of a week is a godsend. Getting others to understand that you need time alone in relative silence for this to happen can be difficult but is well worth the effort for your mental health, even if asking feels uncomfortable. Repeated requests made in a polite yet firm tone are rarely ignored.

As a last resort, exit. A synonym for bathroom is ‘refuge’, of which introverts and HSPs are intimately familiar – sometimes it’s the only way to break up an exhausting day filled with meetings and bellicose coworkers. Conferences are the pinnacle of excess conversation, but luckily more and more venues (including those reserved for EA Global) have some sort of prayer or meditation room where the non-gregarious can convene for much-needed respite.

2. Communicate

The majority of the population is unfamiliar with the concept of HSPS, and as such explaining how members of our species have inherited this trait can be a valuable learning experience if framed correctly. I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how even the most extroverted acquaintances respond positively after hearing an explanation of how high sensitivity is more like a hidden superpower than a source of fragility. The pointy-haired boss will take note of your conscientiousness and communication skills, and has no doubt read management books on the subject of emotional intelligence, an aptitude you can pitch as advantageous. Friends and family members present their own difficulty as they’re used to seeing you in a certain way, but they’ll find that once they begin making small changes to accommodate your disposition the quality of the relationship improves dramatically.

That being said the assertive and occasionally aggressive style of communication that’s the norm in the Americas and much of Europe can go against the HSP’s more empathetic form of relating. When overstimulation happens again and again in a way that doesn’t respect your boundaries, it’s necessary to set limits, which might have to be described forcefully. As with anything this is a trainable skill that feels awkward at the beginning but improves through deliberate practice. Remember that for the less sensitive speaking in a businesslike way is the norm and they’ll quickly understand the tone and word choice. Sample phrases:

“I’d like to help/attend/meet but am only available with advance notice. When would be a good time for you?”

“These kinds of events are very stimulating for me so I’ll only stay for an hour.”

“When you speak with me in that way I feel invalidated, so please make more of an effort to be respectful.”

“I need some ‘me time’ right now so come back later and we can talk.”

“I’m struggling with X and need a listening ear – are you in a place where you can do that?”

3. Self-compassion

Of all Buddhist meditation practices, the type Westerners struggle the most with is metta or loving-kindness. This is partially attributable to the syrupy-sounding name, of which open-heartedness, friendliness, and goodwill are equally valid translations. The underlying reason is the Protestant work ethic that permeates our institutions and culture: you only have worth if you’re working extremely hard. For the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock this was an adaptive way to think as they had to struggle mightily to establish new lives on a different continent, but several hundred years later it’s no longer functional and acts as a subtle contributor to the ongoing mental health crisis. An intrinsic sense of self-worth is out of reach when external success is the benchmark to feel good about yourself.

As a result, the aspect of metta practice we find particularly difficult is directing compassion towards ourselves. The influence of conditional love runs deep and is intensified for highly sensitive persons who have internalized the expectation that being tough and unfeeling to accomplish things is the only correct way to act. This conditioning began from a very young age and takes time to recognize, let alone undo. For that reason it’s common to start the practice by first directing warmth at someone you’re fond of and then progressing towards a neutral person, an irritating person, then finally yourself. Phrases to do so include ‘may you be happy’, ‘may you be loved’, and ‘may you be free from suffering’.

A useful acronym developed by author and meditation teacher Tara Brach is RAIN (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nurture). Sounds straightforward, although for beginners listening to guided meditations or taking an online course can help. Quality books on the subject include Brach’s Radical Compassion and The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook by Kristen Neff and Christopher Germer.

4. Job crafting

The contemporary economy is über-competitive at the best of times, necessitating that many (if not most) people hold jobs that are a far cry from their dream occupation. For the HSP this presents a dilemma as we tend to have a much stronger desire for meaningful work. Philosophical finagling on what constitutes meaning aside, the dreary reality of completing a set of tasks every day just to make a living without contributing to a purpose greater than oneself becomes vitality-sapping. What’s the way out?

Irrespective of the job title and its perceived prestige, there’s room to modify either the expected responsibilities or your perception of them. Doing the former can produce a feeling of discomfort since we’re conditioned to view a job as a fixed list of things to do based on a recruitment posting, but descriptions are more guidelines than actual rules. The only laws that matter are those that are enforced and it’s rare that a manager will criticize someone for putting in a little extra effort if the result adds to the organization’s bottom line. Ways to do this vary depending on the workplace and include improving processes, exploring customer feedback for new product ideas, or finding rare skills to address unmet needs. In a hierarchical corporate structure the leeway to do so might not be there at the beginning so it’s important to establish trust by first demonstrating competence. As positive changes accrue, supervisors will notice, and with luck be more open to suggestions they can take credit for.

In the case of lower autonomy the option to re-interpret one’s circumstances makes the difference between drudgery and determination. Working as a waiter or line cook is a temporary way to pay the bills, or it’s an opportunity to be hospitable to guests who just had a long day and want to enjoy a warm meal in a cozy local restaurant. Pablumic as this might sound there are periods in every life where the luxury of picking and choosing your schedule is unavailable, so following the time-tested wisdom to re-frame rather than resent misfortune is evergreen. This is relevant for (in)effective altruists as given the limited supply of ‘official’ EA positions earning to give remains the most viable strategy for many movement participants. Humiliating work becomes bearable when you know that donating a fraction of the earned income helps some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

Building relationships is another factor contributing to increased job satisfaction. Studies continue to show that the more supportive and friendly an employee’s colleagues are, the happier they report to be. Unglamorous blue-collar occupations such as construction have high retention because of the camaraderie developed while doing hard work for long hours alongside people you’ve learned to lean on. That being said, there are always coworkers that are more difficult to get along with, and the objective isn’t spending hours trying to congenialize the cynics. Focus instead on relational crafting: every interaction has potential for human connection. Routine exchanges with patients, customers, clients, and cross-geographic colleagues transform into convivial conversations once you ask a few (non-intrusive) personal questions. The mental load of a problem you’ve been wrestling with over the past week is lightened after asking for advice from a respected superior. Conversely, setting limits on interactions with high-friction individuals boosts rather than drains your energy.

5. Leverage

In Probably Good’s SELF framework, which is a more grounded alternative to 80 000 Hour’s ITN model, the importance of the actual context that one is operating in is emphasized. Whether you’re aiming to do a lot of good with your career or struggling to fix the office coffee machine understanding the constraints of the environment is key. With sufficient care, over time maneuvers can be made to find a place where your capabilities are well matched to the resources at hand, multiplying your efforts and ensuring that much more money, social capital, or technology are directed towards outsized impact.

For sensitive persons this presents a challenge as we’re not accustomed to being put into positions where our talents are valued. The shameless self-promotion expected by extroverts to gain influence seems egotistical and the default view of sensitivity is dismissive, but these obstacles can be overcome with the right tactics. Areas where HSPs shine such as intuition, creativity, depth, empathy, and attention to detail are re-interpretable in ways that allow one to offer something distinct and overlooked in the typical organization. Rather than crassly selling yourself, think of it as changing the dynamics of the game so that more people are aware of the benefits of sensitivity.

Terms to use:

- Broad perspective-taking

- Deep conceptual connections

- Intuitive and innovative leadership

- Intensity for passion projects

- Problem-solving by switching between levels of abstraction

- Commitment to personal values or company mission

- Self-awareness for energy moderation, burnout prevention

- Considerate compassion

Passion and innovation are of course buzzwords that have been diluted beyond all recognition, so deploying them might be sickening, but sometimes you’ve got to play along. What matters is gaining credibility for making use of the above so that your reputation as a thoughtful yet effective colleague precedes you.

6. Play

As the years accumulate and childhood recedes further into memory, the brightness and spontaneity of our early years fade and are replaced by the unending demands of adulthood. Deadline after deadline grounds down the electricity of being alive while the profit-maximizing pressure of economic incentives has led to the baffling idea that even leisure time should be optimized for peak results, something people living fifty years ago would find insane. Deciding that your mission is to turn your career into a similarly optimal machine for doing good results in a grim orientation where everyday joys are superseded by the cosmic importance of saving lives in expectation or preventing technobiosynthetic Ragnarök. For the unaware HSP, this morphs into deathgrip desperation that encroaches on the basic human need to have fun.

The inverse that cures this modern ailment is what researchers have termed play ethic. In our strange predicament at this moment in history it seems frivolous to do ‘immature’ things like crack jokes during meetings, roll around in the snow, go to amusement parks, and finger the didgeridoo. Isn’t it wrong to laugh while the world burns? Yes and no, depending for how long and whether doing so enables you to relax enough to turn on the fire hose. Some of our species’ greatest minds have discovered that goofing off creates energizing gaps that the brain uses to switch into a diffuse mode of processing where brilliant insights emerge out of the blue. The emittent mathematician John Conway spent a non-trivial amount of time playing backgammon and Phutball, hobbies among others he credited with contributing to his discoveries including the Monster symmetry group and the emergent phenomena Game of Life.

7. Embrace it and make yourself useful

In his anti cult of productivity book Four Thousand Weeks, author Oliver Burkeman describes an episode in the life of Carl Jung when as a boy the future psychological theorist was knocked unconscious during a game, which he then decided to use as an excuse to faint whenever he encountered a difficult math problem. This soon led to staying at home all day, a vacation from school he enjoyed until overhearing a conversation between his father and a visiting friend where Paul Jung lamented how his son had been diagnosed with epilepsy and would never be able to support himself. Carl immediately recognized his error in avoiding effort and went up to his father’s study to throw himself into learning. After fainting three more times he overcame the internal resistance, which served to set the foundations for a work ethic and curiosity that led to prolific output, eventually changing the course of psychology as a discipline.

Modern readers find much of analytical psychology to be mythical rather than scientific, and rightfully so, but I’ve included this example to illustrate one of Jung’s most important and helpful ideas: the life task. It’s likely that there’s something you need to do that for whatever reason you’ve been avoiding. In the EA context maybe it’s mustering the courage to apply for that job or contact that person whose work you admire, or maybe it’s the opposite – finally dropping out of the ‘top-ranked’ graduate program because you were never that interested in gaining an Oxbridge/Ivey League elite-approved credential in the first place and the material has gone sour. Maybe it’s getting back into a creative hobby for its own sake or introducing yourself to the cute librarian. Or maybe it’s consciously deciding to commit yourself to an occupation, relationship, or city, because some things only have a chance to bloom with time.

Whatever it might be, I invite you to pause and consider the following: what’s the life task you’re presented with? Given what you now know about high sensitivity, what does that imply for your actions over the next few weeks?

Most people face several such turning points and I don’t mean to suggest that there’s a single one that finding your one true calling hinges on. Life is fundamentally unpredictable and the best we can do is learn through trial and error, which can be off-putting to admit for the rationally inclined but is unavoidable. My aim in including this question is to give you the momentum to move forward in the area of personal growth you’ve been postponing, as months of delay quickly turn into years. The number of days you have left is a finite yet unknowable number and it’s a tragedy to let them slip by, regardless of any world-changing aspirations. No one can choose for you but neither can anyone prevent you from choosing.

My story, i.e. the emotional punch needed for this to stick

The outline of this post included a section for the narrative arc of my involvement with the EA movement and the subsequent trauma which has scarred my nervous system, but given that it’s become more of a literature review nearing ten thousand words adding a lengthy personal description would be excessive. It’s enough to say that the chronic stress of the pandemic coupled with social isolation in an unsupportive university environment and constant exposure to cataclysmic AI visions created an abyssal downward spiral that I’m still recovering from. The beautiful dream of scientific positive impact turned into a waking nightmare that will take years to forget and any potential I had after graduating from engineering school has been glassed, the fields of my life burned and the earth salted. My priority is now slowly regenerating the natural curiosity that propelled me to be captivated by this philosophical project.

It’s of course impossible to turn back the clock to see how my decisions would’ve changed knowing what I do now, and I’m not sure I would choose to do so given the option. At this point the damage has been done and it’s better to learn from my mistakes and help others. The classic advice still rings true: don’t be bycatch. No matter how well-meaning they seem funders, IYIs, community builders, and Bay Area netizens are constrained by their own incentives and are unable to understand the unique set of circumstantial experiences that make you a complex individual. Absent of vigilance, your values will be captured by externally determined preferences from what has become a powerful group of institutions – one more body amongst foundations.

The ambiguity of finding your deepest impulse can be painful, but following it is vastly preferable to being subject to the cognitive homogenization that comes with subservience to social machinery. The most accomplished altruists in history didn’t decide in advance that they were going to ‘maximize’ their impact through an approved method and work backwards to crunch themselves into the kind of person capable of doing so. They moved forward towards what they found compelling for its own sake, which through a combination of skill and luck produced astounding results. More importantly, they enjoyed themselves by pursuing their intrinsic interests instead of losing sleep over abstract representations of doing good.

Personal fit dominates all other concerns: there’s no use getting a fancy title at a fancy think tank if your gut instinct is telling you that pursuing a more meaningful but less impactful path is the humane option. Experience gained from interacting with reality is more reliable than endless theorizing, and ultimately it’s up to the individual to decide how to live amidst the inchoate uncertainty, tragedy, and beauty of this impermanent world. You’ve been given this one life, so to use Zen teacher Taizan Maezumi's expression appreciate it and take care of it. Time passes swiftly by.

Conclusion

In sum, high sensory processing sensitivity is a variation of the nervous system that makes an organism more responsive to stimulus. Being sensitive is perceived as a drawback by Western cultural norms yet with self-knowledge measures can be taken for highly sensitive persons to protect themselves from overstimulation and modify their environments so they can thrive. With patient effort a vocation can be found that matches an individual’s temperament and interests, which might include aiming for a particular measure of positive social impact.

Writing this has been cathartic as it allowed me to make sense of not only pandemic-induced difficulties but my own developmental trajectory, stretching back to the challenging periods of early adulthood and adolescence. HSPS remains underappreciated as a psychological trait and I hope that people in this community will benefit to the degree I have from learning. An analogy to consider: everyone’s character is like that of a video game protagonist with points assigned to different abilities. No one gets to choose how the points are assigned to them at birth, and there’s no ideal distribution, but it’s always possible to begin again by deciding to move in a life direction better matched with your disposition.

Some of our species’ most talented, accomplished, and admirable members have exhibited high sensitivity[1] and counting yourself among them is a cause for celebration. Sense with pride to make use of your natural gifts for your own benefit and that of others, and enjoy the dance while it lasts. Thanks for reading and best of luck 🤠

References

Aron, Elaine N. 2020. The Highly Sensitive Person: How to Thrive When the World Overwhelms You. Citadel Press.

Granneman, Jenn, and Andre Sólo. 2023. Sensitive: The Hidden Power of the Highly Sensitive Person in a Loud, Fast, Too-Much World. New York, NY: Harmony Books.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/61327444-sensitive

Acevedo, Bianca, Elaine Aron, Sarah Pospos, and Dana Jessen (2018). The Functional Highly Sensitive Brain: A Review of the Brain Circuits Underlying Sensory Processing Sensitivity and Seemingly Related Disorders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 373, no. 1744. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0161

Greven, Corina U.; Lionetti, Francesca; Booth, Charlotte; Aron, Elaine N.; Fox, Elaine; Schendan, Haline E.; Pluess, Michael; Bruining, Hilgo; Acevedo, Bianca; Bijttebier, Patricia; Homberg, Judith (2019). “Sensory Processing Sensitivity in the context of Environmental Sensitivity: A critical review and development of research agenda.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews Elsevier. 98: 287–305. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.009. hdl:2066/202697. PMID 30639671.

Lionetti, F., Aron, A., Aron, E.N. et al (2018). “Dandelions, tulips and orchids: evidence for the existence of low-sensitive, medium-sensitive and high-sensitive individuals.” Transl Psychiatry 8, 24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-017-0090-6

Pluess, Michael; Belsky, Jay (2013). "Vantage Sensitivity: Individual Differences in Response to Positive Experiences" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 139 (4): 901–916. doi:10.1037/a0030196. PMID 23025924.

Wolf, Max; Van Doorn, G. Sander; Weissing, Franz J. (2008). "Evolutionary emergence of responsive and unresponsive personalities". PNAS. 105 (41): 15825–15830. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805473105. PMC 2572984. PMID 18838685.

- ^

Suspected HSPs, past and present:

Shunryu Suzuki, Leonard Cohen, Anthony Bourdain, Till Lindemann, Frank Zappa, Lana Del Rey, Marshall Mathers, Fred Rogers, Bob Ross, Julia Wise, William MacAskill, Nassim Taleb, Michael Burry, Phil Ivey, David Goggins, Jim Carrey, Nicolas Cage, Louis C.K., Paul Erdős, Norman Borlaug, Roger Penrose, David Foster Wallace, Dita Von Teese, Susan Cain, Nelson Mandela, Oprah Winfrey, Claude Shannon, Yoshua Bengio, Martin Luther King Jr., Richard Nixon, Alan Watts, Vincent Van Gogh, Isaac Newton, Leonardo da Vinci

Evidently this list is mostly populated with white men, so please comment with suggestions of your own from more diverse backgrounds if any come to mind!

Thank you Philippe. A family member has always described me as an HSP, but I hadn't thought about it in relation to EA before. Your post helped me realize that I hold back from writing as much as I can/bringing maximum value to the Forum because I'm worried that my work being recognized would be overwhelming in the HSP way I'm familiar with.

It leads to a catch-22 in that I thrive on meaningful, helpful work, as you mentioned. I love writing anything new and useful, from research to user manuals. But I can hardly think of something as frightening as "prolific output, eventually changing the course of ... a discipline." I shudder to think of being influential as an individual. I'd much rather contribute to the influence of an anonymous mass. Not yet sure how to tackle this. Let me know if this is a familiar feeling.

Glad you found the post useful!

Yes I've held back on contributing to the forum for much the same reason, and there's nothing wrong with living a quiet life and adding what you can to an important cause. Being either locally or posthumously famous is a more reasonable and attainable goal for most people anyhow :)

If you qualify as a Highly Sensitive Person, IMO it's also worth considering whether you're autistic; as far as I can tell, the two are synonyms.

That's a common misconception, as autism can include hyper reactivity to sensory input overlapping with many of the symptoms described above but also hypo reactivity i.e. reduced reactivity to sensory input. I'm not an expert in ASD diagnosis but common features seem to include repetitive behaviours, social skills deficits, and unusually systematized thinking. Perhaps you can comment on your own experience or that of someone you know?

Executive summary: High sensory processing sensitivity (HSP) is a trait that affects a significant portion of the population, including those in the Effective Altruism (EA) community, impacting their experiences and interactions with the world in profound ways.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

I'm not very confident on this topic. I was also evaluated as a very weak-hearted and sensitive person. I don't think it's up to me to discuss whether they exist or not. But it's very difficult because HSPs are a shield for many people. I have observed something close to “covert narcissism.” I would like to point out that they tend to describe themselves as "competent and in need of protection." They want to be overly privileged.

Interesting, I hadn't considered that. Sounds similar to the phenomenon of 'spiritual bypassing' among meditators where emotional/relational issues are ignored after achieving a certain level of awakening. Something to keep in mind