TLDR: This report explores the idea of incubating a nonprofit organization seeking to convince governments and the food industry to lower the content of salt in food by setting sodium limits and reformulating high-sodium foods.

We’re looking for people to launch this idea through Ambitious Impact (Charity Entrepreneurship) next August 12-October 4, 2024 Incubation Program. No particular previous experience is necessary – if you could plausibly see yourself excited to launch this charity, we encourage you to apply by April 14, 2024.

Research Report:

Advocacy for salt intake reduction

Author: Morgan Fairless

Review: Samantha Kagel, Sam Hilton

Date of publication: February 2024

Research period: 2023

We are very grateful to Joel Tan of the Centre for Exploratory Altruism Research (CEARCH) for the extensive support and advice on this research. This investigation has greatly benefited from prior work by CEARCH on the same subject.

We are also grateful to Aidan Whitfield for his collaboration in this research and work on potassium-enriched salt substitutes, which benefited this investigation.

Finally, many thanks to Dr. Bruce Neal and Chris Smith who took the time to offer their thoughts on this research, and all Charity Entrepreneurship staff for their contributions to this report.

For questions about the content of this research, please contact morgan@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the research process, please contact Sam Hilton at sam@charityentrepreneurship.com.

Executive summary

Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) fosters more effective global charities by connecting capable individuals with high-impact ideas. In 2023, CE investigated ideas related to sustainable development goals and potential neurotoxicants or toxic substances.

This report discusses the merits of sodium reduction through food reformulation.

Salt is a silent killer, leading to millions of deaths due to cardiovascular disease per year due to diets high in sodium. Given dietary changes, population aging, and lifestyle changes, the burden of cardiovascular diseases related to sodium consumption is expected to grow (Olsen et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2023e).

Limiting sodium consumption levels is largely regarded as a cost-effective way of reducing the burden of cardiovascular diseases at a population level (Watkins et al., 2023). We recommend that a new non-profit organization focus on leading food producers to reformulate their products in line with safe limits. We think this is promising because it does not rely on individual behavioral changes and can leverage the State and food producers to reach a large scale.

A new non-profit organization could combine advocacy and technical assistance to lead the State and food producers to cooperate and reduce the level of sodium in popular high-sodium foods. Complementary interventions, such as front-of-pack labeling and fiscal approaches, may support these goals.

This is high-risk high-reward intervention. We estimated that non-profits have successfully led to food reformulation, achieving both policy change success and correct implementation, in ~10% of their advocacy attempts. It may take multiple attempts and careful targeting for a new organization to achieve change. Yet given the cost-effective intervention, this low-success scenario is likely still worth pursuing.

Overall, there is evidence of a likely reduction in sodium intake due to reformulation, based on primarily observational longitudinal studies documenting the reduction of sodium consumption drops following reformulation interventions. This is not very high-quality evidence but is in line with expectations for an evidence base for a policy in this space. Experts largely agreed with our conclusions.

We identified several countries where this intervention is needed, and change would be most viable. The tentative list of countries includes Indonesia, Romania, Japan, Slovakia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia, Hungary. The report discusses other potential priorization strategies.

Our speculative cost-effectiveness model, as well as other CEAs in the literature, suggest that sodium policy is highly cost-effective. Our modeling suggests that in Indonesia this intervention may avert 866 DALYs for every USD 1,000 spent (90% CI -4 - 3045; corresponding to about a USD 1 per DALY, 95% CI inv. CI 0 - 1000). In Georgia, it may avert 13.8 DALYs for every USD 1,000 spent (95% Confidence Interval 0.3 - 47.5; corresponding to $72 per DALY, 95% CI inv 21 - 3333).

Overall, we believe this is an idea worth recommending for incubation. A new organization focused on sodium reduction policies (especially reformulation) is highly likely to be cost-effective and address a real and growing burden.

1 Introduction

This report evaluates the idea of sodium reduction through food reformulation concerning its promise for the Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) Incubation Program.

CE’s mission is to cause more effective non-profit organizations to exist worldwide. To accomplish this mission, we connect talented individuals with high-impact intervention opportunities and provide them with training, colleagues, funding opportunities, and ongoing operational support.

CE researchers chose this idea as a potentially promising intervention within the broader areas of (1) the best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals and (2) the burden of neurotoxicants and other dangerous substances. This decision was part of a multi-month process designed to identify interventions that are most likely high-impact avenues for future non-profit enterprises.

This process began by listing hundreds of ideas, gradually narrowing them down, and examining them in increasing depth. We use various decision tools such as evidence reviews, theory of change assessments, group consensus decision-making, case study analysis, weighted factor models, cost-effectiveness analyses, and expert inputs.

This process is exploratory and rigorous but not comprehensive – we did not research all ideas in depth. As such, our decision not to take forward a non-profit idea to the point of writing a full report does not reflect a view that the concept is not good.

.

2 Background

2.1 Cause area

In this research round, CE focused on two areas within human development and health: (1) the best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and (2) the burden of neurotoxicants and other dangerous substances. Researching these two areas meant evaluating ideas from various fields, including maternal health, chronic diseases, neglected tropical diseases, migration, public administration governance, neurotoxins, and education.

We considered the different types and variety in the overall quality of evidence one can expect from each field and the limitations of comparing interventions across different cause areas, where different metrics would often be prioritized or preferred. As individuals with experience with CE’s research process will have noted, the diversity within a research round is often limited to avoid these limitations. As such, this research round differed in some ways from the way CE conducts research within a specific cause area.

Best targets within the Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are a mechanism designed to focus global action toward specific objectives. Like the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) before them, these goals aim to redirect efforts and funding toward an agreed-upon list of priorities. They were agreed to by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly as part of its post-2015 ambitions (Wikipedia contributors, 2023c). Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs have grown significantly in number of goals and targets (from eight to 17 and 21 to 169, respectively).

Figure 1: The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals

The global community succeeded in some of the most critical MDGs. MDG targets related to poverty reduction and safe drinking water, among others, were met. Despite missed targets, observers have noted the role of a concise list of eight priorities in focusing energies and driving progress. By drawing comparisons to the MDGs, observers have criticized the SDGs for being too many in number and too broad in substance (Lomborg, 2023; The Economist, 2015).

Progress toward achieving SDG goals has stalled. Only 15% of SDG targets are on track to completion, 48% are moderately or severely off-track, and 37% are regressing or stagnating (United Nations Publications, 2023).

This research round aimed to investigate if a non-profit organization of the style CE incubates could cost-effectively support the progress toward the goals and associated targets. We used the list of goals from the Copenhagen Consensus’ Halftime to the SDGs project as an initial departure point, listing all interventions prioritized in that project and supplementing the list with research from other sources, such as the Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel’s smart buys in education (Banerjee et al., 2023), and our own brainstorming and consultation exercise.

2.2 Topic area

This report evaluates the viability and desirability of a non-profit organization focused on reformulating products high in sodium. To achieve this, we envision that an organization will dedicate itself to advocacy within government to achieve public health legislation and policies supportive of reformulation. We think the most promising policy will likely be introducing sodium limits. Fiscal incentives, front-of-pack labeling, and other options may support similar outcomes. While the non-profit organization will ultimately choose specific country recommendations, we expect sodium limits to be the priority intervention in this space.

Sodium and hypertension, a short primer

Table salt – largely composed of sodium chloride (NaCl) – is a central element of most diets worldwide. Salt has been used for centuries for preservation and flavor enhancement, leading to it playing a central role in history (Wikipedia contributors, 2023a). Humans need small amounts of sodium for our nerve impulses and muscles, as well as to maintain the right balance of water and minerals (The Nutrition Source, 2023).

Despite being a necessary mineral for human health, the over-consumption of sodium leads to higher blood pressure. Though there is no defined threshold, when high blood pressure is persistent, this is often classified as hypertension. Hypertension contributes to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (The Nutrition Source, 2023). With the advent of ultra-processed foods and high-calorie, nutrient-poor diets, most people in the world now consume too much sodium, leading to health complications.

The main mechanism through which sodium leads to poor health outcomes is its contribution to hypertension. The relationship between sodium consumption and increases in blood pressure is well-established by a series of high-quality studies (Appel et al., 1997; Cook et al., 2007, 2009; Intersalt Cooperative Research Group, 1988a; Sacks et al., 2001). The mechanism leading to this relationship has to do with several interlinked and quite complex factors, including

- A genetic predisposition including salt sensitivity (Maaliki et al., 2022).

- Aging, which leads to blood vessel stiffening (Oparil et al., 2018).

- The effects of high sodium on gut microbiota (Oparil et al., 2018).

- The effects of high sodium on endothelial function and changes to the structure of blood vessels (Youssef, 2022).

- The interplay of sodium, water retention, and increases in cardiovascular pressure (Oparil et al., 2018).

To put it in simpler terms, high blood pressure leads to a higher workload for the heart, which, over the long term, can cause changes in how it works and lead to poor health outcomes. When high sodium consumption leads to higher blood pressure, that increased pressure can cause changes in the heart's structure and some blood vessels, which – through the damage – increases the risk of several CVDs, such as heart failure and stroke (Tackling & Borhade, 2023; Zhou et al., 2021).

While the risk of CVD is by far the most significant contributor to the sodium-linked disease burden, high sodium consumption can also lead to renal diseases and stomach cancer. High sodium can cause increases in urinary protein, leading to kidney disease; it can also cause increases in the activity of the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, linked to inflammation and ulcers leading to stomach cancer (Action on Salt, 2023b, 2023c).

Our decision to research sodium reduction

CE decided to investigate sodium consumption reduction for several reasons:

- The contribution of sodium to hypertension is well-established. Hypertension is a significant contributor to mortality and morbidity due to CVD (Oparil et al., 2018).

- The burden of hypertension is widely expected to grow in future years (Olsen et al., 2016).

- Sodium reduction strategies are expected to be very cost-effective (Tan, 2023b; Watkins et al., 2023; Webb et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2023e)

- When reviewing options for salt reduction public health policies, we were encouraged by the wide spectrum of strategies available and some previous successes.

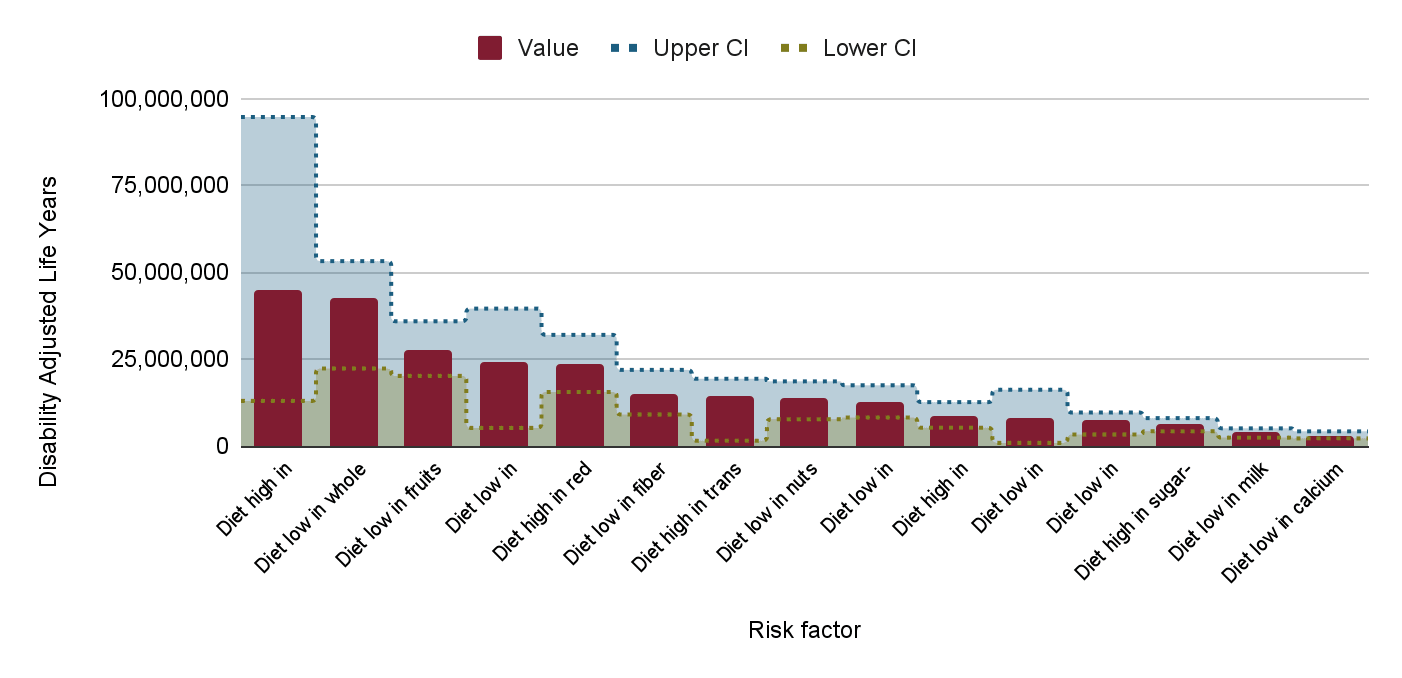

Sodium consumption is among the largest modifiable risk factors contributing to mortality and morbidity worldwide, leading to 1,885,355 deaths in 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2020). Figure 2 shows the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study data on all dietary behaviors it tracks as risk factors. A diet high in sodium is the leading dietary risk factor regarding the raw number of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost globally.

Figure 2: Total Number of DALYs lost by dietary risk factors in 2019 globally (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2020)

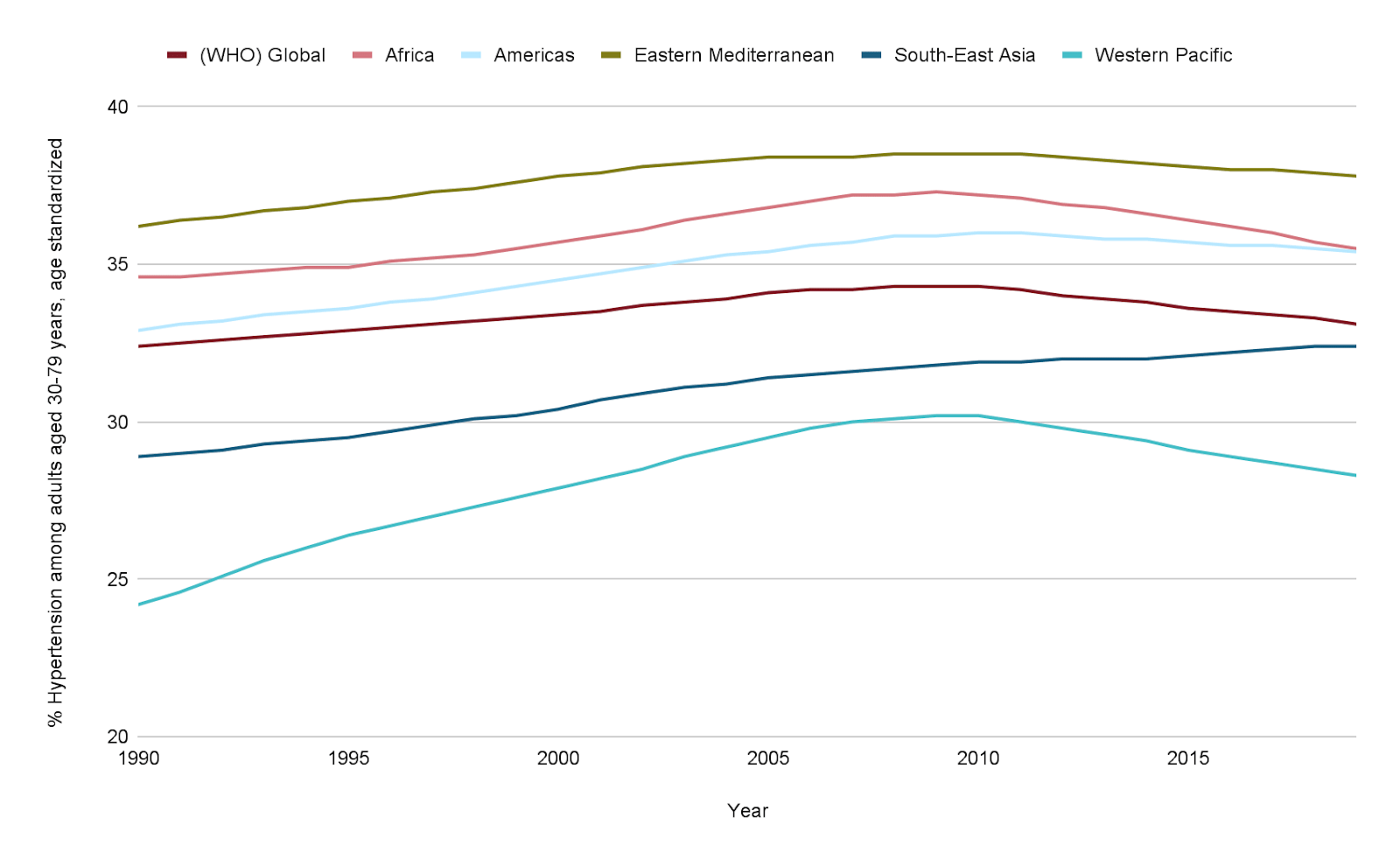

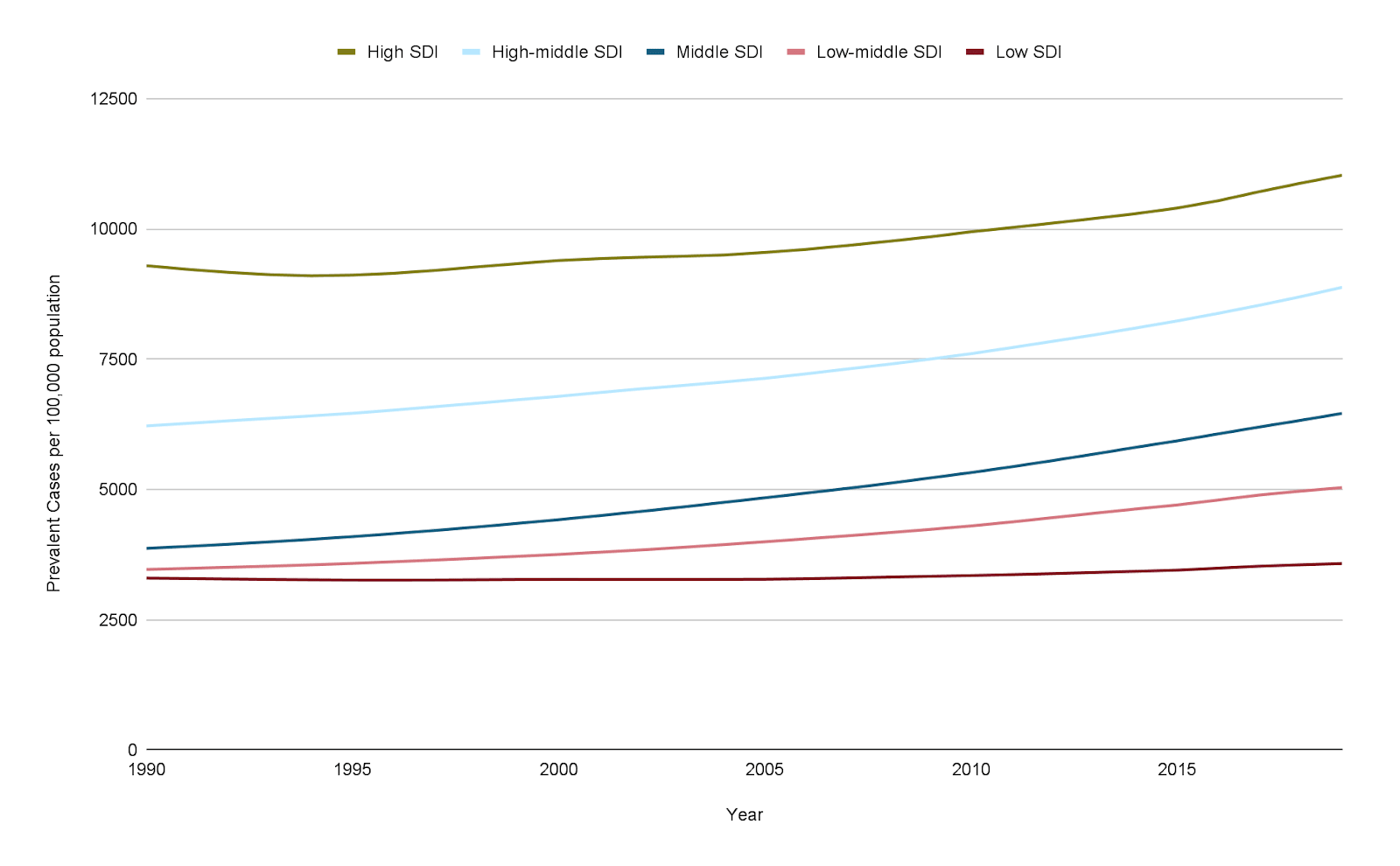

Unlike many major diseases, the long-term outlook for the CVD burden is negative. Due to demographic and developmental changes – such as nutritional transitions toward ultra-processed foods and aging populations – the burden of hypertension-linked CVD is widely expected to increase (Olsen et al., 2016; Oparil et al., 2018). Figures 3 and 4 show historical trends in CVD and hypertension – note that the figures show a growth in the DALY burden without reflecting other factors, including population growth and aging.

Figure 3: Prevalence of CVD per 100,000 population 1990-2019, by development status (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, 2020)

Many countries have implemented strategies to reduce sodium consumption with detectable health gains at the population level. We discuss these strategies in depth in further sections of this report.

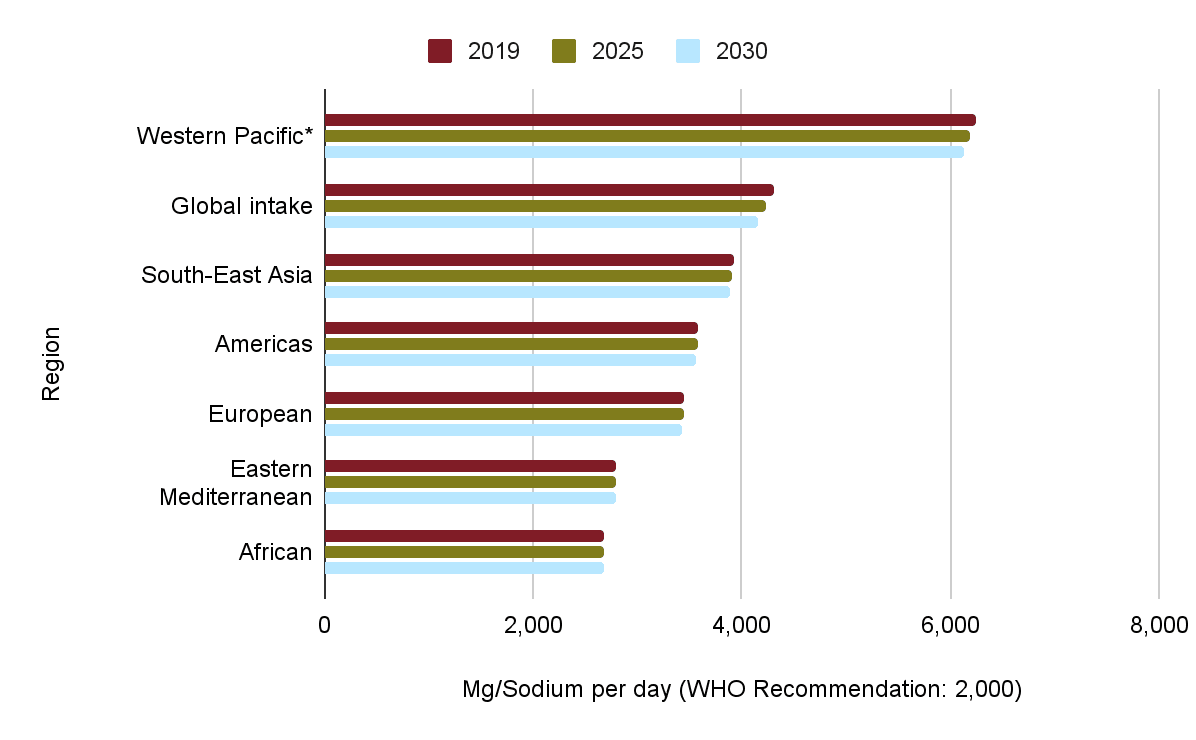

Figure 5: Average sodium consumption across regions (source: World Health Organization, 2023f, p. 41)

Disease management and sodium reduction

There are many activities to strengthen along the spectrum of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment within the management of hypertension. These include preventative steps such as lifestyle changes and pharmacological approaches, improving diagnostic and screening practices, and treating hypertension once identified to prevent it from leading to CVD (Oparil et al., 2018, p. 1).

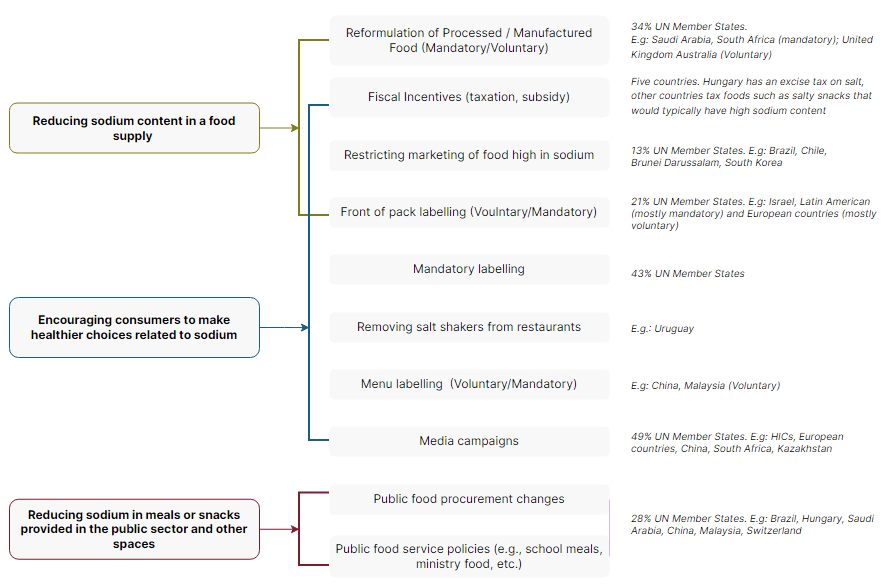

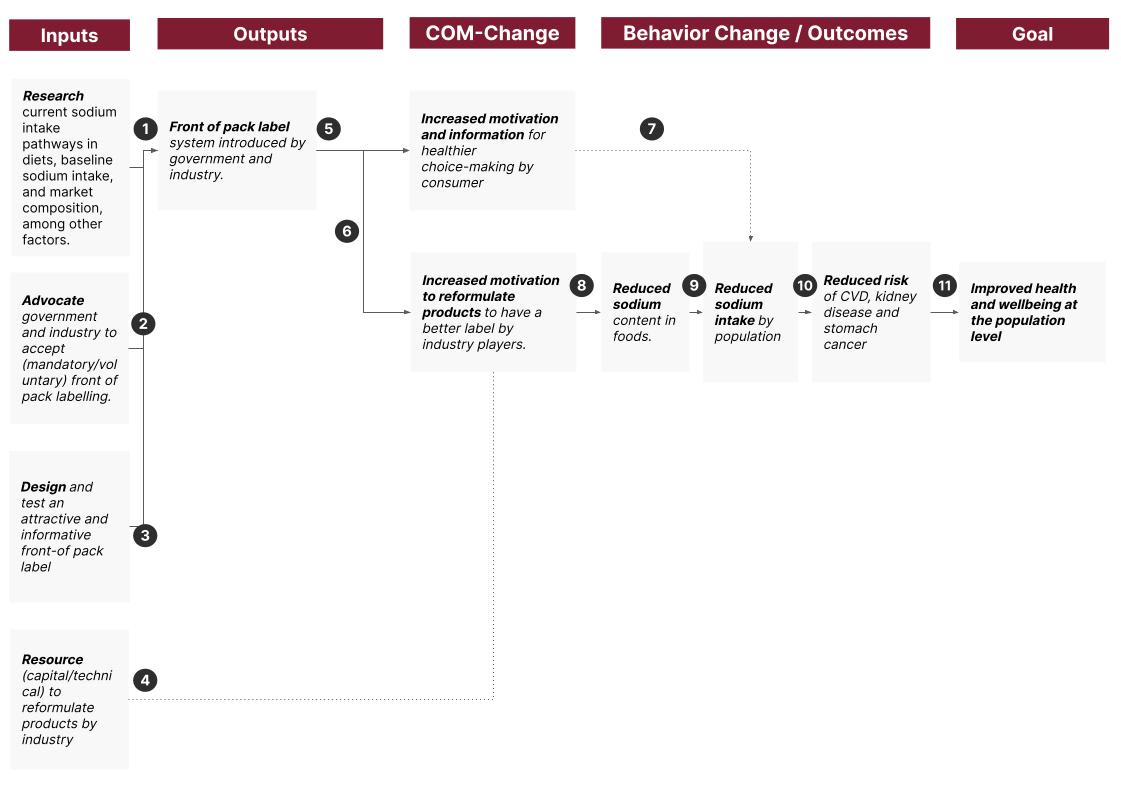

We focus on prevention because we expect some public health approaches to reducing sodium consumption to be very cheap, reach a large scale quickly, and require very few purposeful behavioral changes from individuals. Figure 6 shows a mapping we conducted of several approaches used (alone or in combination) to reduce sodium consumption at a population level.

Figure 6: Public health approaches to reducing sodium consumption

As Figure 6 shows, there are a wide range of policy options available to lower sodium consumption – a large part of our efforts in this report focus on investigating which ones are the most promising (and for what context).

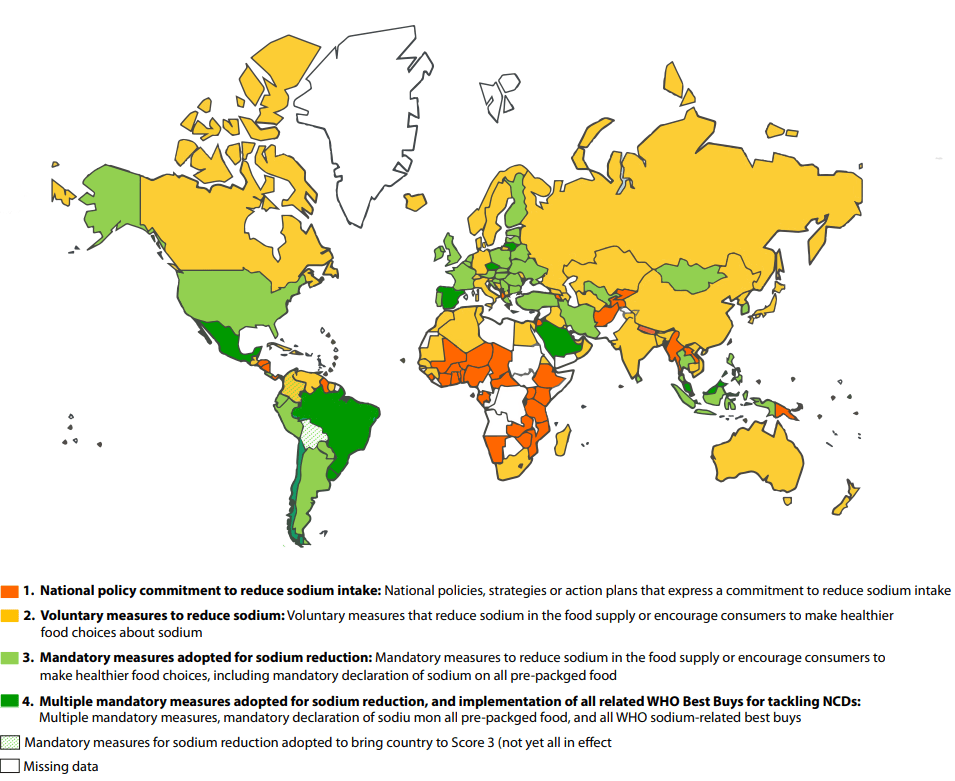

Several countries have implemented actions to reduce sodium consumption across their populations. So far, it has been chiefly affluent countries that have made progress. The best available policy coverage data comes from the WHO – we think this dataset likely overcounts coverage by considering local policies as a marker of national progress and neglecting implementation quality and status. According to this data, only 55% of UN member states have implemented sodium reduction policies, with the most popular among them being voluntary media campaigns (around 50% of members), reformulation (around 35%), and healthy public food procurement (about 30%).

There are consistent discrepancies among regional and income groups regarding the implementation of mandatory vs. voluntary mechanisms and the type of policies involved (World Health Organization, 2023f). For instance, no low-income countries are implementing mandatory or voluntary food reformulation or healthy public food procurement, and only 15 and 14 (out of 53) lower-middle-income countries are implementing these (respectively) (World Health Organization, 2023f).

Figure 7: WHO Sodium Reduction Country Score Card (source: World Health Organization, 2023f, p. 33)

Does this intervention make sense in Low and Middle-Income Countries?

The relevance of this intervention for some countries, such as Sub-Saharan African countries, could be questioned, given that the prevalence of hypertension-linked disease is lower, and so is sodium consumption.

While it is true that the immediate counterfactual impact of reducing sodium intake in a country with a more considerable CVD burden will likely be higher, we note that secular trends in sodium intake and the prevalence of CVD show growth across most countries. Additionally, consumption of sodium is regardless too high based on WHO targets (Oyebode et al., 2016). To that end, work in countries where sodium consumption is above the WHO recommendation but relatively lower may help curb future trends and prevent the take-off of nutritional changes.

Additionally, there is much disparity between countries and what their primary sources of sodium are (Bhat et al., 2020). This intervention works best for countries where people take most of their sodium from non-discretionary sources. We think this is a better way to divide countries based on suitability for this intervention than SDI.

3 Theories of change

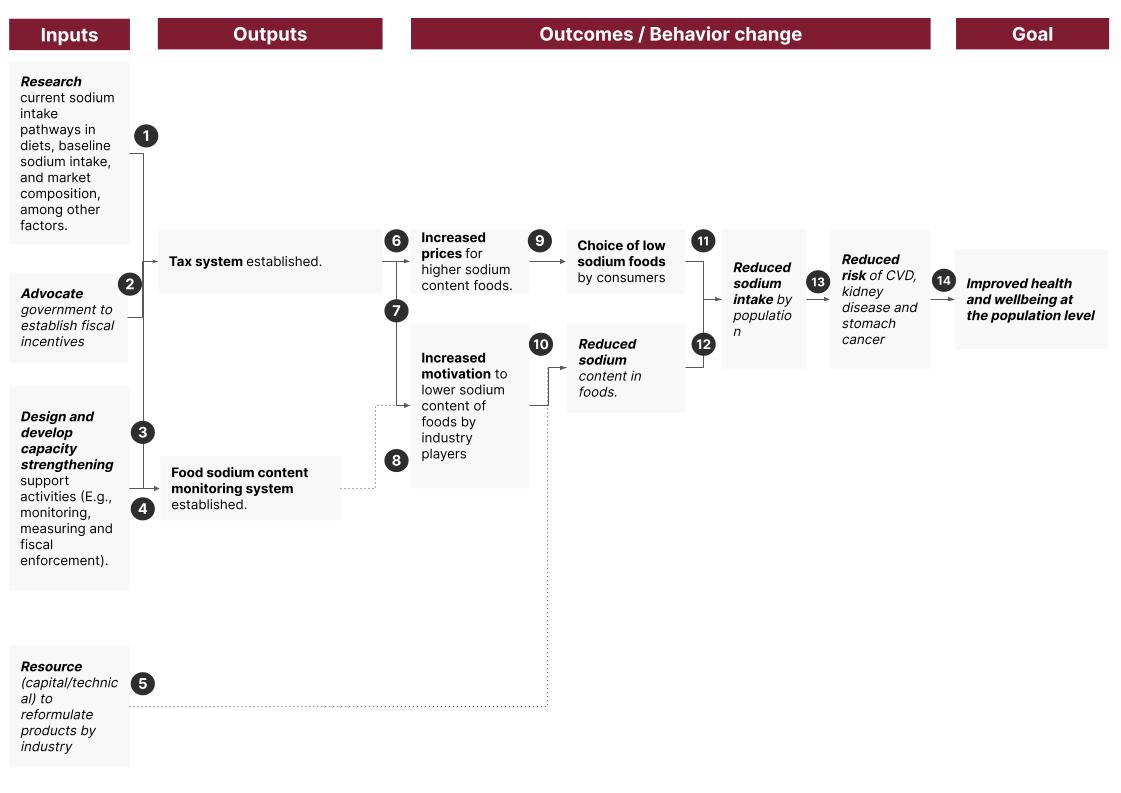

This section discusses what we believe is the most robust theory of change (ToC) for a new organization working on reducing sodium intake through public health approaches.

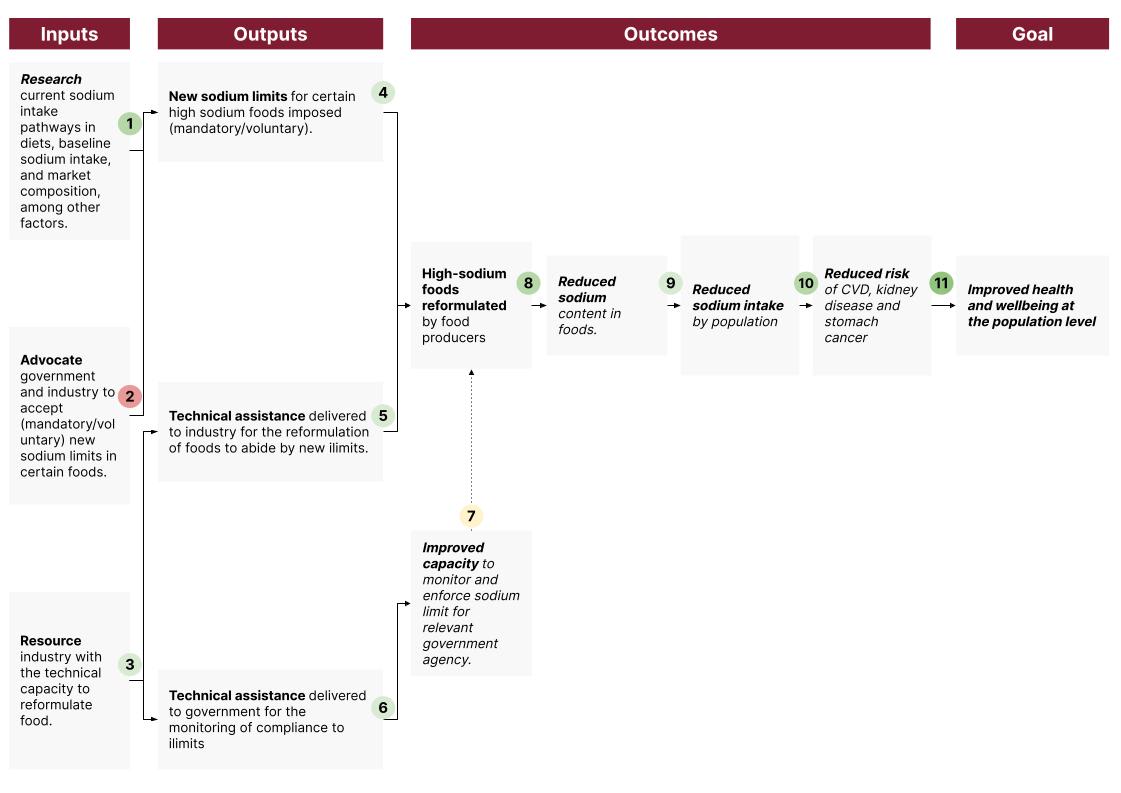

We recommend that an organization focus on getting food producers to reduce the sodium content in their foods by reformulating their products. A new organization could advocate for (preferably) mandatory or voluntary reformulation alongside legislation on sodium limits.

Other strategies, such as fiscal approaches, front-of-pack labeling, and healthy public food procurement, can be considered. Still, we mostly view them as a means to change the policy environment and lead producers to reformulate. Annex 3 includes ToCs for other strategies to support policy goals, depending on the context.

Beyond advocacy, an organization may deem it necessary to tackle associated barriers, such as a lack of upfront investment for reformulation, technical capacity, and formative research. Our research has identified these elements as potential hindrances to either achieving the introduction of new policies or their correct implementation (Section 4.1).

The non-profit will need to adapt the intervention to the context based on several considerations, such as:

- History of previous policies (E.g., have some policies been introduced? Has the country made commitments? Has the industry made commitments? Have some advocacy efforts failed?).

- Dietary profile of the country, including largest sodium sources (e.g., processed foods, home cooking, cooking sauces).

- Cultural and contextual dietary practices (e.g., traditional food high in sodium, communal dining, most meals in fast food restaurants or outside the home).

- Food production market shape (e.g., reliance on imports, highly concentrated processed food market, primarily small-scale producers).

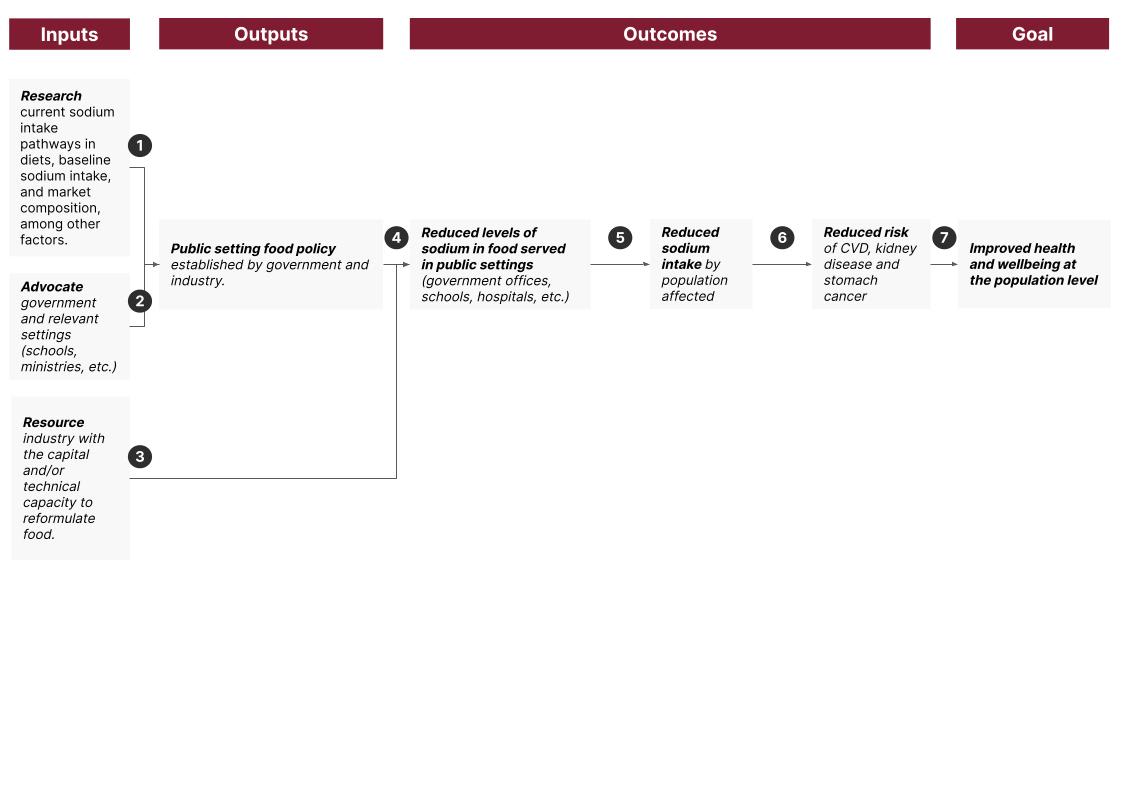

Figure 8 provides a ToC showing how we think a non-profit organization can support governments in reformulating high-sodium foods and, therefore, improving health and well-being.

Figure 8: Theory of Change

We assess each causal pathway and our confidence below:

- We have identified that a lack of formative country-specific research (e.g., diet studies, studies of the food industry, and sodium intake monitoring) can be a barrier to introducing new sodium limits and other sodium reduction policies. We therefore think it is very likely (80-95% chance) that a new organization will conduct some form of formative assessment.

We think it is very likely (80-95% chance) that a CE-style charity can either establish the right connections with academic institutions to fund and deliver this research or conduct it based on prior CE-incubated charity experiences.

- We think it is very unlikely (we use around 10% chance in our CEA) that an organization will achieve policy changes in line with health recommendations, given past attempts in this and similar areas. See section 4.

Even though achieving the top-recommended policy change is challenging, a new non-profit organization should be able to pivot relatively quickly to new countries or approaches. We think a vast repertoire of potentially effective (and cost-effective) policy alternatives exists.

- We think it is likely (55-80%) that a CE-style charity can furnish itself with the capacity to deliver technical assistance by hiring nutritionists and food scientists. We base this on previous CE-incubated experiences, such as LEEP. We expect that technical assistance may be needed to support food producers in reducing sodium in foods without affecting the taste and other qualities of the product.

- We are unsure whether part of the activities required in any given country may require supporting industry with upfront costs and technical inputs for reformulation. We do not model upfront commodity costs but do model some technical support to large food producers.

- In countries with a strong expectation of competent enforcement, we think it is probable (55-80%) that after some time for readjustment, most food producers would abide by new limits. We back up this point with research cited in Section 4.

- Where enforcement capacity is lower, we expect compliance to be lower, and therefore, expected reductions in sodium contents may not reach the mandated limits. Given the lack of studies in LICs looking at the enforcement of sodium limits, we are uncertain what degree of compliance to expect. See section 4 for more information on this question.

- We expect industry actors to be interested in cost-saving, retaining clientele, and abiding by laws ahead of their interest in population health matters. Therefore, we suspect successful technical assistance support will take the form of supporting adaption to new limits while ensuring food quality is retained.

It is likely (55-80%) that, given technical assistance, firms can reformulate products to abide by sodium limits. Given that the same products sold by multinational companies often have wildly disparate sodium contents, we expect that reformulating products is a manageable challenge and can be done without sacrificing commercial interests. Acceptability studies have shown sodium levels can be lowered in several products while still retaining customer acceptability (Links Community, 2022, sec. 2.6)

- We expect that in some cases, governments will require some assistance from civil society to enforce new legislation or voluntary commitments. A new organization is likely (55-80%) to be able to support the government by building testing capacity (for the food supply and sodium intake).

- Enforcement may or may not be necessary to ensure sodium reductions. We are highly uncertain about the relative contribution of enforcement actions to the overall causal chain. Theoretically, if the industry expects to avoid incurring costs for breaking new sodium limits, it will keep the status quo and not reformulate.

- As discussed in point six, we think that some expectation of enforcement is required to ensure firms abide by new limits. We think that this assumption has roughly even odds of holding (45-55%) to hold, but are unsure of the degree to which high degrees of enforcement are required (i.e., we think some expectation of enforcement is needed but do not know how much enforcement is required for firms to change behavior). However, the enforcement capacity will vary across countries and even industries. Therefore, we cannot provide a reliable baseline view of our expectation that enforcement will occur.

- We think it is very likely (80-95%) that food will have less sodium if firms reformulate their products.

- We think it is likely (55-80%) that reduced sodium content in foods leads to reduced sodium intake. The degree to which sodium intake is actually reduced will depend on the number of products reformulated and dietary practices, among other factors. We discuss this and associated caveats in section 4.

- We think it is very likely (80-95%) that reduced sodium intake at a population level reduces the risk of poor health outcomes. We explore this more in section 4.

- We are almost sure (95-99%) that reduced sodium-related risks at the population level will lead to better health outcomes and improved well-being.

4 Quality of evidence

We consider four research questions in our evidence review:

- RQ1: How strong is the evidence that a charity can achieve policy commitments in line with sodium reduction priorities?

- RQ2/A: How strong is the evidence that sodium reformulation can reduce sodium consumption at the population level?

- RQ2/B: What is required for sodium reduction policies to succeed?

- RQ3: How strong is the evidence that reduced sodium consumption leads to improved health outcomes?

4.1 How strong is the evidence that a charity can achieve policy commitments in line with sodium reduction priorities?

We conducted an evidence review (unsystematic) on this question, querying any type of academic or grey literature from the 1990s onward (we considered that any earlier policy context may not bear much resemblance to contemporary contexts). Given that this is a question of policy success, we expected to find mostly case studies and qualitative studies tracking the introduction of different policies. The question of the likelihood of success is difficult to quantify, and one should generally not expect the type of clear-cut answers from other types of literature. Introducing policies and health reforms is path- and context-dependent, and – ultimately – very contingent. Due to publication bias, we did not expect to find many written-up cases of failure.

Our overall conclusion is twofold: a. A. Achieving policy change success and successful implementation has a low probability (~10%) per attempt; b. a new non-profit will be able to maximize its chances within that by correctly understanding barriers and designing a strategy to surmount them. Additionally,

- Previous country experience suggests that most – documented – efforts have been concentrated in higher-income countries, but progress in LMICs is viable.

- Civil society organizations and pressure groups have played key roles in several success cases, most importantly in the UK.

- The identified barriers, particularly a lack of funding and formative research, seem addressable, and there is a track record of successful approaches to resolving them.

Achieving significant policy changes is challenging, and our baseline view of the chance of success for this type of activity is low. The Centre for Exploratory Altruism Research (CEARCH), a CE-incubated charity, has investigated hypertension policy and different advocacy attempts in-depth; they suggested to us that from their experience, organizations are successful in about 15% of their attempts. It may take multiple attempts and careful targeting for a new organization to achieve policy change.

Implementing these policies is feasible – many countries have achieved some degree of sodium reduction policy success, suggesting that the path is not uncharted (Santos et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2023f). As noted in section 1, more than 50% of UN member states implement some form of policy on sodium reduction. The United Kingdom (UK), Japan, and Finland are frequently cited as policy successes, given that they not only introduced the necessary policies but also achieved the outcome of reducing sodium consumption (He & MacGregor, 2015; McLaren, 2012).

Conversely, some countries have made little progress despite increased efforts. For instance, the US made limited progress (between 2010 and 2019) in implementing 2010 recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine – in particular, the Food and Drug Administration has only published voluntary guidance and has received extensive industry pushback against those and the plan for mandatory reductions (Musicus et al., 2020). Nutrition policy became marred in political opposition, to the point that the Trump administration rolled back much of the progress (such as sodium reduction in schools) – reportedly, the Biden administration is pushing to revert to course and increase efforts as part of its diet-related disease policy (Qiu, 2023). Despite being a leader in some aspects of sodium reduction, Portugal’s parliament rejected a sodium tax in 2018, recommending instead a “co-regulation agreement with the food industry to achieve similar changes in consumption of salt” (Goiana-da-Silva et al., 2019, p. 1).

Civil society has played an important role in several identified policy successes:

- For instance, the introduction of reforms in the UK is attributed by some to the academic experts who set up an action group (Consensus Action on Salt and Health, CASH) – “CASH was very active and was ultimately successful in a) engaging the food industry in sodium reduction (CASH managed to persuade a major supermarket and several food companies to reduce added salt); and b) convincing the government to reverse its 1996 decision and endorse COMA’s original target of <6g salt/day (<2,358 mg sodium/day)” (He, Brinsden, et al., 2014; McLaren, 2012, p. 16).

- CEARCH notes that World Action on Salt, Sugar, and Health (WASSH) has claimed several achievements, with clear contributions to policy success in the UK, Portugal, and Australia, as well as “significant involvement” in China, Malaysia, South Africa, and the Gulf States (Action on Salt, 2023a, para. 5; Tan, 2023b).

- The Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC) funded a consortium of five Latin American research centers to develop context-specific evidence for dietary policy (identified as a key barrier for policymaking). According to a qualitative post-program review, the funding has effectively contributed to the development of policy-relevant research and raised the issue of sodium reduction in the policy agenda. The evaluation of some intermediate outcome successes, including the addition of sodium reduction to policy agendas in Peru, revision of sodium consumption targets in Argentina, regional commitments from the Pan American Health Organization, and leading to further funding from Resolve to Save Lives for social marketing (Padilla-Moseley et al., 2022, p. 11).

Richer countries find it easier to introduce these policies. Higher-income countries have been faster to introduce these, which we think makes sense given differences in capacity for policymaking and the need to prioritize different needs across low-income countries (Mancia et al., 2017). Policy success has mostly come from HICs, especially concerning policy outcomes.

However, the introduction of these policies is not limited to just HICs.

- Latin American countries, mostly LMICs, have seen more success than other LMIC regions, suggesting once again that introduction is feasible but also reinforcing the importance of government capacity and relative wealth (given that Latin American countries tend to be on the richer end of the spectrum in LMICs) (Flexner et al., 2020; Padilla-Moseley et al., 2022; World Health Organization, 2023f).

- A study by Webster et al. (2022) suggests that introduction success is also possible in LMICs by documenting the introduction of salt reduction policies in Argentina, Mongolia, South Africa, and Vietnam. Other studies have documented appetite and efforts to introduce these public health approaches in LMICs (Trieu et al., 2018).

- China’s “Shandong province (population 96 million) (...) [introduced] expanded blood-pressure screening and treatment, and driving changes in social norms by supporting health-promoting environmental policies. These strategies were implemented in concert with a surveillance system, funding mobilizations, and the strengthening of the local capacity of health services. Provincial and local government agencies and health-sector teams target interventions in household and educational settings such as elementary schools, and also prehypertension and hypertension populations from a representative study cohort selected by a complex, four-stage cluster sampling with strategic partners such as the food industry, businesses, and restaurants to reduce sodium intake. The mid-term evaluation reported decreased per-person seasoning salt intake in Shandong from 12·5 g to 11·58 g per day.” (Olsen et al., 2016, p. 30).

- Fiscal policies related to sodium intake or healthy eating have been introduced in Mexico, Tonga, Fiji, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Hungary (Olsen et al., 2016).

There seems to be some momentum in the growth of countries introducing this sort of policy, which may bolster the argument for new countries to introduce them. According to Santos et al. (2021), the number of countries implementing sodium reduction policies increased by around 134% between 2010 and 2014 and 28% between 2014 and 2019. The WHO seems to be advocating for these measures and monitoring their introduction more heavily, for instance, by publishing Country Salt Score Cards and their first report on global sodium intake reduction (World Health Organization, 2023f).

We expect some pushback but think it is surmountable. There is a strong expectation that the industry may push back against regulation efforts, as has happened in several countries worldwide on many policy fronts, and in sodium reduction in particular (Musicus et al., 2020). However, the South African experience of being one of the first countries to set mandatory sodium limits shows that the desired policies can be successful. Despite some industry pushback, South African media was reportedly mostly favorable to the regulations (despite some “nanny state” objections and noting bread price rises) (Hofman, 2013). In the UK, the threat of regulation seems to have been used to achieve voluntary engagement.

Table 1: Seeming enablers and barriers to introducing public health approaches to sodium reduction.

| Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|

|

|

4.2 Do sodium reduction policies work to reduce sodium consumption?

This sub-section focuses on RQ2/A: How strong is the evidence that reformulation can reduce sodium consumption at the population level? and RQ2/B: What inputs and outputs are required for reformulation to succeed?

This section focuses on reformulation as a policy option. We have moved most of our notes on other approaches to annex 4.

We conducted an evidence review (unsystematic) on these questions, querying any type of academic or grey literature.

Our top-level conclusion from the evidence is that reformulation is a key component to most multi-component interventions at the population level and will likely reduce sodium consumption. The evidence for this comes mostly from pre/post studies that have documented decreases in sodium consumption in years following the introduction of new approaches.

Table 2 summarizes our sense of the level of evidence and support for each component.

Table 2: Summary of evidence and recommendations

| Component | Likely causal pathway | Evidence summary | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reformulation | Ensures sodium-high foods have lower sodium contents by working with industry. | It will likely lower sodium consumption if implemented and well-targeted, based on straightforward ToC.

Supported by real-world case studies, mostly from HICs and South Africa. Evidence quality is low for these studies.

Systematic reviews of empirical and modeling studies expect consequential sodium. It is reductions. | Very likely to be a core component of any policy package we recommend to the government and industry.

Mandatory reformulations are superior to voluntary ones if introduction is possible. |

| Front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) | Incentives for industry players to reformulate to avoid negative consumer associations. | The evidence for changes in consumer behavior is, on balance, negative. Consumer behavior studies are mostly disparate in results obtained but mostly show a lack of success in shifting toward lower sodium intake.

A handful of studies support the main causal pathway, suggesting that after FOPL is introduced, some industry players will reformulate. The evidence quality supporting this claim is of low quality. | It could be part of any policy package we recommend to the government and industry. It is mainly a supporting element to reformulation, given it rewards collaborators and punishes those who avoid it.

|

| Fiscal incentives | Incentivices consumption of lower sodium foods and/or the reformulation of foods by industry to prevent higher consumer prices. | Empirical evidence is significantly mixed throughout the quality spectrum. From experimental to observational studies, cross-price elasticities make it challenging to predict what would happen.

On the other hand, modeling studies are primarily positive in expecting a reduced sodium intake. | Roughly even odds of becoming part of a recommended strategy or lower. We think fiscal incentives are potentially useful as an additional incentive to industry. Still, careful monitoring and modeling should be conducted to understand the potential effect of a fiscal incentive, given the background of the target population. |

| Public-setting food policies | Mandatory reductions in sodium in settings where people often have at least one meal, like schools or hospitals. | Empirical evidence supports the introduction of these policies, particularly in schools. The evidence is of low-medium quality. | We think the introduction of this strategy will depend on the overall strategy of the non-profit. We view these policies as good to have but on a considerably lower scale.

If the policies affect industry, say by changing what the State purchases, they may be used as an additional incentive to cooperate in reformulation. |

Establishing the impact of any one policy is a major challenge due to the multi-component nature of most public health interventions and the observational nature of the evidence. Most countries have attempted several approaches simultaneously, making it difficult to disentangle any effects separately.

Further, we expected most, if not all, of the evidence available will come from pre-post and modeling studies.

A 2016 Cochrane review supports multi-component approaches to sodium consumption reduction through structural public health approaches (such as reformulation). Their conclusions come from ten initiatives marked very low through the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) method, given the risk of bias and variation in results. We expected this, given the observational nature of the studies. “Five of these showed mean decreases in average daily salt intake per person from pre‐intervention to post‐intervention, ranging from 1.15 grams/day less (Finland) to 0.35 grams/day less (Ireland). Two initiatives showed a mean increase in salt intake from pre‐intervention to post‐intervention: Canada (1.66) and Switzerland (0.80 grams/day more per person); however, in both countries, the pre‐intervention data point was from several years before the initiation of the intervention. The remaining three initiatives did not show a statistically significant mean change. (...) Seven of the ten initiatives were multi‐component and incorporated intervention activities of a structural nature (e.g., food product reformulation, food procurement policy in specific settings). Of those seven initiatives, four showed a statistically significant mean decrease in salt intake from pre‐intervention to post‐intervention, ranging from Finland to Ireland (see above), and one showed a statistically significant mean increase in salt intake from pre‐intervention to post‐intervention (Switzerland; see above).” (McLaren et al., 2016, para. 11).

How strong is the evidence that reformulation of processed/manufactured foods (mandatory/voluntary) can lead to a reduction in sodium consumption at the population level?

Table 3 shows our review of the evidence for this approach. Note this is not a comprehensive account of all papers that mention the topic. Still, it provides an overview of key results.

Overall, there is evidence of a likely reduction in sodium intake due to reformulation, based on primarily observational longitudinal studies documenting the reduction of sodium consumption drops following reformulation interventions. There is decent evidence that countries that have enacted policies to reduce sodium through reformulation have achieved some success. Given the quality of the evidence, we cannot fully discard spurious changes and omitted variables. Our understanding is that sodium intake has increased worldwide, suggesting that if a country has managed to decrease it over time, it may be bucking a trend. Therefore, the policy may be having a counterfactual impact.

We think it is very likely that mandatory reformulation outperforms voluntary reformulation in terms of the magnitude of the effect. This is based on empirical evidence and the common sense notion that if the policy is mandatory, it will imply higher levels of compliance and, thus, more significant drops in sodium content (Hyseni et al., 2017).

Table 3: Evidence summary: Reformulation

| Study | Context | Methodology & loose assessment of the quality of evidence | Main conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reformulation alone. | |||

| Federici et al. (2019) | Mostly HIC country contexts. |

|

|

| Gressier et al. (2021) | Multiple |

|

|

| Hyseni et al. (2017) | Multiple. |

|

|

| Charlton et al. (2021) | South Africa, two years after mandatory limits on sodium imposed |

|

|

| As part of multiple-component approaches. | |||

| He et al. (2014) | The UK’s approach, including reformulation (voluntary), labeling, and health promotion |

|

|

| Webster et al. (2011) |

|

|

|

We think it is straightforward that well-targeted mandatory reformulation would decrease sodium content in foods and thus sodium intake. The logic behind this intervention makes it almost certain that the sodium content of foods would decrease if the intervention is well-executed. Nevertheless, there are several reasons why the effect may be lower than expected or non-existent in the face of a mandatory reformulation policy:

- If a country’s food intake largely relies on imports and the policy does not affect imported foods.

- If most of the sodium intake across the country comes from added salt during cooking (for instance, if the diet is not largely dependent on processed foods, ready meals, sauces, stocks, etc.). To clarify, this does not include added salt through processed sauces and additives, which would be impacted (and may be the core focus) by reformulation.

What is required for each approach to succeed?

This sub-section seeks to clarify implementational matters – we have reviewed the chances of achieving policy introduction in section 4.1. We try to clarify what we think are the cruxes for each one. We primarily rely on expert commentary cited in Tan (2023b), a short review of implementation and process studies, and our expert consultation.

Instead of focusing on each component, we focus on key elements identified in the ToCs (see section 3). Table 4 discusses our findings.

Overall, we think that it is very likely that implementation support will be a necessary condition for success. Country experiences suggest that the richer the country, the easier the implementation of sodium reduction. If a new organization is to work in resource-constrained countries, it will most likely need to support technical inputs for implementation, including increased surveillance of sodium intake.

We expect this type of support to be tractable. Past country experiences, including in LMICs, suggest that targeted support can be implemented to achieve policy success in line with ambitions. We do not think this policy area is overly complex given that 1. It is not overly controversial from a policy point of view, and 2. It is not overly technically complex to reformulate foods or monitor progress.

Table 4: Evaluation of implementation factors of concern

| Element | Comments |

|---|---|

| Industry reformulation of foods | Lack of manufacturer capacity to scale-up salt substitutes and make reformulations mentioned as barriers in Argentina, Mongolia, and South Africa. Industry competition and government technical support have been noted as enablers (Webster et al., 2022).

Opposition from industry and the promotion of their standards can be cumbersome. The establishment of quality standards is noted by experts as “ These are low cost, sustainable, and more effective than consumer education and information” (Allemandi et al., 2022; Mozaffarian et al., 2018, p. 3). |

| Consumers making healthier choices | Lack of baseline awareness noted as a challenge, as well as cultural adherence to high-sodium foods (Blanco-Metzler et al., 2021; Trieu et al., 2018; Webster et al., 2022).

The effects of FOPL seem to be hindered by complex and difficult-to-interpret labeling (Mozaffarian et al., 2018). |

| Establishing a new tax, sodium limit, or legislation. | For this and similar policy-level matters, it's important to remember that many governments have bandwidth issues beyond technical capacity for implementation. One potential solution is to embed technical and focused capacity into ministries (Tan, 2023b).

Policy evaluation capacity in some LMICs is low, leading to a lack of adaptive management and amendments to policy (Tan, 2023b).

Expertise to coordinate policy across several ministerial responsibilities is limited in some countries. Coordination support may be needed (Allemandi et al., 2022; Mozaffarian et al., 2018).

Funding for implementation of policies, once enacted, is often low or non-existent, as evidenced by experiences in the Americas (Allemandi et al., 2022). |

Monitoring

| (1, 2) Lack of access to laboratory equipment and high laboratory costs have been mentioned as barriers to surveillance in Mongolia and South Africa. Success in this area has been facilitated by the development of standard operating procedures for testing, the involvement of national governments, and the introduction of strong experts in monitoring. (Allemandi et al., 2022; Webster et al., 2022).

(2) 24-hour surveys are the gold standard but are burdensome for participants and researchers. Spot urine tests are less logistically challenging and have been used with some success to predict 24-hour excretion in low-income settings. There is no widely accepted formula to do this, though (de Boer & Kestenbaum, 2013; McLean, 2014).

(1 and 2) According to the UN Global Health Observatory, in 2021, just under 40% of all countries had conducted a recent (i.e., in the past five years), national adult risk factor survey including sodium intake. Of those who had conducted surveys, only eight were from African countries, and seventeen were in Asia or the Pacific (World Health Organization, 2023b).

(2) In a country survey, Hawkes and Webster (2012) identified that of the 30 (out of 45 country respondents) countries that identified as having formal national assessments of salt intake, close to three quarters were high-income. |

| Encouraging lower sodium cooking and menu design in public settings. | Chef and manager training is a significant enabler for sodium reduction in menus (Webster et al., 2022).

Limited budgets in settings such as schools and hospitals can hinder implementation if lower sodium foods are more expensive (Mozaffarian et al., 2018). |

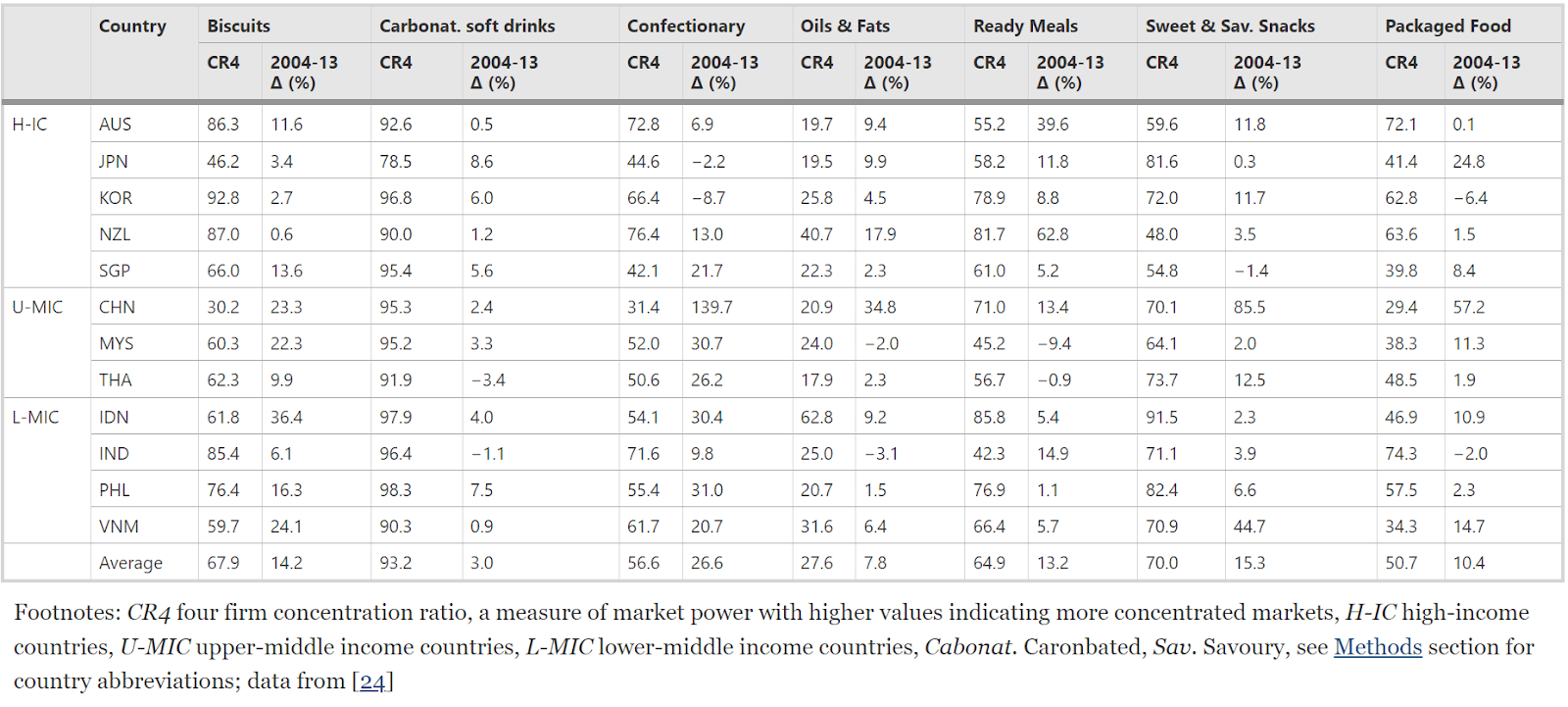

The role of the food industry and dietary sources of sodium

The non-profit will have to consider two factors carefully when deciding upon a country to focus on and overall strategy:

- The size and fragmentation of the food industry.

We think targeting countries with a consolidated food market – meaning that a few players control a large proportion – would be a better choice for two reasons. In a consolidated market, the nonprofit will:

- Have to lobby fewer actors to reach policy success and support fewer actors with any reformulation needs.

- Reach a larger scale through the actions of a few actors.

Different ratios can be used to calculate market concentration, such as the four- or eight-firm concentration ratios, which provide the market share of the four or eight largest players (respectively) (FasterCapital, n.d.). We could not find a unified database of indicators for a concentration metric but we suggest that understanding concentration will be relevant to the non-profit organizations’ actions. We suspect more industrialized and richer countries may have more concentrated markets due to a larger reliance on ultra-processed foods. Some academic studies may be used to access market concentration data (e.g., Baker & Friel, 2016; Van Dam et al., 2022).

To test whether the information could be found and would inform strategy, we tried to find concentration ratios for food industry sub-sectors in Indonesia (the top country in the geographic assessment at the time of conducting the assessment). Nauly et al. (2020) suggest that some of the most concentrated sub-sectors in the food industry in the country are “food-seasoning industry (0.933), processed food (0.896), other processing and preserving fish (0.893), macaroni and noodles (0.866)” (p.74) – we think these will also be among the highest sodium foods in people’s diets.

- Dietary sources of sodium

Reformulation is a good strategy for countries where a large proportion of sodium intake comes from non-discretionary sources. Discretionary sources relate to salt added during cooking or at the table.

Dietary sources of sodium vary widely across countries, with some studies identifying an inverse correlation between GDP and the proportion of salt coming from discretionary sources (Bhat et al., 2020). Bread, cereals, and ultra-processed foods are most often the largest sources of dietary sodium across countries (Bhat et al., 2020).

The non-profit should take care to evaluate the nutritional profile of a country and its changing nature. For example, Ahmed et al. (2023) note in The Guardian how high-sodium instant ramen noodles are taking over new markets in lower-income countries where their low price is very attractive. Likewise, soy sauce, fish sauces, and other condiments often constitute a source of discretionary intake, yet they can be modified to be low-sodium (Tan, 2023b).

4.3 Evidence that the change has the expected health effects

This sub-section summarizes the evidence on the impact of reducing sodium intake on the health burden. The relationship between sodium consumption and hypertension is well established by expert consensus and several high-quality studies: frequent overconsumption of sodium contributes to persistent high blood pressure, which can lead to cardiovascular issues. We, therefore, did not spend many resources investigating it further (He & MacGregor, 2011; Intersalt Cooperative Research Group, 1988b; Tan, 2023b; Whelton, 2015). We mostly focused on whether there is evidence that these public health population-level interventions impact health.

The WHO endorses the evidence that sodium reduction reduces the burden of CVD. For instance, it suggests that a two-score uplift in its Sodium Score Card (see figure 7) from 2019 to 2025 and then 2030 would have a large impact on health-related burdens (see table 5) (He & MacGregor, 2015, p. 10; World Health Organization, 2023f).

Table 5: CVD deaths averted by sodium reduction policy improvements worldwide (source: World Health Organization, 2023f, p. 42)

2025 | 2030 | |||

CVD aggregated deaths averted (millions) | % of deaths | CVD aggregated deaths averted (millions) | % of deaths | |

| Africa | 0.087 | 1.3 | 0.278 | 2.3 |

| Americas | 0.199 | 1.4 | 0.628 | 2.5 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 0.086 | 0.9 | 0.275 | 1.6 |

| European | 0.293 | 1.1 | 0.903 | 1.9 |

| South-East Asia | 0.507 | 1.8 | 1.62 | 3.1 |

| Western Pacific | 1.022 | 2.5 | 3.242 | 4.4 |

| Global | 2.194 | 1.7 | 6.946 | 3.1 |

Experiments where individuals are randomized into sodium reduction have mainly indicated a decrease in risk of CVD and lower blood pressure. Still, these are not population-level interventions and sometimes have very narrow sample population characteristics. Experiments of sodium reduction have shown significant and non-significant reductions in blood pressure and - in a minority of cases - CVD mortality (Chang et al., 2006; Whelton et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2023). Observational follow-ups of randomized trials found non-significant associations between lower sodium intake and CVD risk (note that non-significance could be related to lack of effect or power) (Cook et al., 2007). One of the largest such experiments, a cluster randomized trial of 600 Chinese villages (n=20,995) with participants over 60 years old or with a history of stroke identified that “the rate of stroke was lower with the salt substitute than with regular salt (29.14 events vs. 33.65 events per 1000 person-years; rate ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77 to 0.96; P=0.006), as were the rates of major cardiovascular events (49.09 events vs. 56.29 events per 1000 person-years; rate ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.94; P<0.001) and death (39.28 events vs. 44.61 events per 1000 person-years; rate ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.95; P<0.001).” (Neal et al., 2021 abstract)

Several high-quality systematic reviews have concluded that there is a relationship between reducing sodium intake and reduced blood pressure, including

- A Cochrane review by He et al. (2013) of 34 RCTs (n=3230) with a modest reduction in salt intake and duration of at least four weeks, which observed that a mean reduction of 4.4 g per day of salt intake led to a mean change in blood pressure of -4.18 mmHg (95% CI = -5.18, -3.18, p<0.00001). The authors concluded that “a modest reduction in salt intake for four or more weeks causes significant and, from a population viewpoint, important falls in BP in both hypertensive and normotensive individuals, irrespective of sex and ethnic group” (p.2)

- A systematic review by Aburto et al. (2013), which investigated studies in adults and children

- In adults, their meta-analysis of 36 studies (n=~6740), found that reducing sodium intake reduced systolic blood pressure by “3.39 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 2.46 to 4.31 mm Hg) and resting diastolic blood pressure by 1.54 mm Hg (0.98 to 2.11)” (p.4). Studies that compared larger and smaller reductions in sodium intake showed results consistent with the notion that larger reductions have an effect of higher magnitude on blood pressure. “Increased sodium intake was associated with an increased risk of stroke (risk ratio 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.43), stroke mortality (1.63, 1.27 to 2.10), and coronary heart disease mortality (1.32, 1.13 to 1.53)” (p.1)

- In children, their meta-analysis on nine controlled studies (n=~1380) showed that reduced sodium intake was associated with “decreased resting systolic blood pressure by 0.84 mm Hg (0.25 to 1.43 mm Hg)” (p.5).

The relationship between increased blood pressure and CVD is well established, with higher blood pressure leading to increased risks of CVD. We cover this topic in section 2.

Some studies have shown a relationship between lower sodium intake and CVD outcomes (Milajerdi et al., 2019). In particular, a meta-analysis from He and MacGregor (2011) identified a 0.80 (0·64–0·99) risk ratio of CVD events from a reduction of 2 and 2.3 grams of salt daily. Strazzullo et al. (2009) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of “19 independent cohort samples from 13 studies, with 177 025 participants (follow-up 3.5-19 years) and over 11 000 vascular events” (Abstract), finding that “higher salt intake was associated with greater risk of stroke (pooled relative risk 1.23, 95% confidence interval 1.06 to 1.43; P=0.007) and cardiovascular disease (1.14, 0.99 to 1.32; P=0.07), with no significant evidence of publication bias” (abstract).

Finally, some longitudinal data from countries implementing successful sodium reduction policies suggest a potential benefit. For instance, He et al. (2014) show a decrease in stroke mortality of 42% (p<0.001) and in ischemic heart disease of 40% (p<0.001) between 2003 and 2011 in England, occurring alongside sodium intake reduction among other factors (lower smoking prevalence, etc.).

5 Expert views

We consider the expert views noted in CEARCH’s extensive interviews with actors in this space and academic experts (Tan, 2023b) . CEARCH and CE have similar research approaches. Their report makes detailed notes available (Tan, 2023a). We additionally spoke to Dr. Bruce Neal, executive director of the George Institute for Global Health (see our interview notes here).

After over 20 years of working on sodium reduction, Dr. Neal noted he is pessimistic about the prospects of advocacy success, citing the constraints of working with a very large number of industry players and the power of the food industry in general. He favored reformulation through ambitious sodium limits as a preferred policy, noting that past efforts (such as South Africa) have not led to large enough reductions and lack of enforcement. He also said past behavioral change efforts have not led to much success.

Dr. Neal said he is very enthusiastic about the prospect of potassium-enriched salt substitutes, which he says bring benefits of both sodium reduction and potassium supplementation, as well as being well-tolerated and highly adhered to.

Table 6: Summary of expert input (source: Tan, 2023a)

| Topic | Summary |

|---|---|

| Likelihood of advocacy success |

|

| Likelihood of reversal of sodium reduction policies if policy introduced |

|

| Current government action |

|

| Future government action |

|

| Current and future NGO actions |

|

| Funding and talent situation |

|

6 Geographic assessment

6.1 Where existing organizations work

Given its popularity as a cost-effective tool to tackle NCDs, it is unsurprising that we found several high-profile organizations and multilateral channels through which action on sodium reduction occurs.

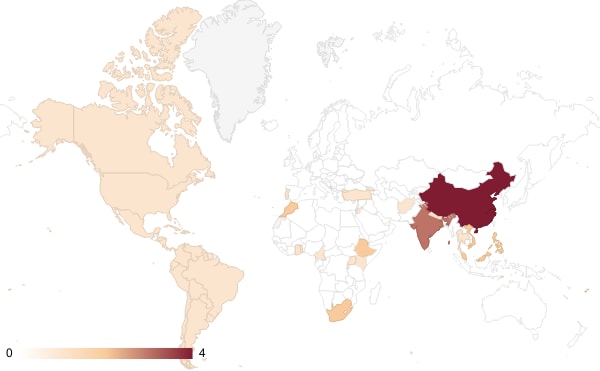

Table 7 shows some organizations we identified, and Figure 10 shows a world map color-coded by the number of organizations present.

Table 7: Organizations we identified

| Organization | Description | Where they work | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolve to Save Lives (RTSL) | Multilateral and national advocacy and coordination, mostly through work with partners. It funds national and regional activities. | Afghanistan, Argentina, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bhutan, Bolivia, Brazil, Burundi, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Timor-Leste, Ecuador, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jamaica, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Montenegro, Morocco, Nepal, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, South Africa, Suriname, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Uganda, United States of America, Uruguay, Venezuela, Vietnam. | https://resolvetosavelives.org/where-we-work/ |

| World Action on Salt, Sugar and Health | Multilateral and national Intensive advocacy and coordination. | China, Jordan, Malaysia, Morocco, Portugal. | https://www.worldactiononsalt.com/projects/ |

| World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Population Salt Reduction | Multilateral and national intensive research, as well as advocacy. | China, Ethiopia, Fiji, India, Samoa, Vietnam. | https://www.whoccsaltreduction.org/what-we-do/?_project_status=active |

| Imagine Law | Philipines based organization, focused on evidence-based policy. | Philippines | https://www.imaginelaw.ph/ |

| RADA | A multi-focus organization based in Cameroon with a program on sodium reduction. | Cameroon | https://recdev.org/our-vision/ |

| Heart and Stroke Foundation | A heart disease organization based in South Africa. | South Africa | https://heartfoundation.co.za/ |

| Members of the World Heart Federation | We expect that members of the federation will be supportive of sodium reduction. | https://world-heart-federation.org/ | |

| Members of the NCD Alliance | The NCD Alliance, and its members, coordinate and lead advocacy efforts. | https://ncdalliance.org/who-we-are/ncd-alliance-network | |

| The George Institute For Global Health | An Australian global health institute, leads the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Population Salt Reduction and has some additional research and advocacy projects on sodium reduction. | China, Fiji, India | https://www.georgeinstitute.org/projects/ |

Figure 10: Map of where organizations are potentially working (numbers indicate the number of organizations present, not the depth at which they work)

6.2 Geographic assessment

We conducted a geographic assessment to understand which countries could be the most promising for a new organization to work in.

Our logic for prioritizing countries was to include measures of the burden, neglectedness, and potential tractability in each country. Table 8 shows the factors we included and our rationale for including them. Table 9 shows the resulting country prioritization.

Table 8: Elements of our geographic assessment.

| Indicator | Definition (Source) | Rationale | Weight |

| Unlikely to be neglected | Countries marked TRUE are those where three or more organizations are present. | This is a qualitative exercise to exclude countries we find unlikely to need more organizations or where more organizations may be counterproductive. | Exclusion |

| Very unsafe countries | Top 16 (spot 15 shared by two countries) in the Fragile States Index - Security data. (link). We also added North Korea and a few other challenging countries to the list. | We think some countries are just too dangerous to work in for most incubatees. Therefore, we avoid the top unsafest countries. | Exclusion |

| High Income Country | Is a HIC (link) | We think that the counterfactual impact of working in richer countries will be lower due to several reasons, including 1. it will be more expensive to work in these countries; 2. it is likelier that these countries are better at screening and treatment, lowering the burden per individual suffering from CVD; 3. it is likelier HICs that are amenable to introducing sodium regulation will have done so, given the rate of introduction of these policies in HICs relative to other countries. | Exclusion |

| DALY Burden CVD (per 100,000) | Rate of Disability Adjusted Life Years lost, per 100,000, 2019, due to Hypertensive heart disease. "Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a general term for conditions affecting the heart or blood vessels." (Link) | To understand the relative contribution of heart conditions to the DALY burden without accounting for population size. | 5% |

| DALY Burden - CVD (total) | Total Disability Adjusted Life Years lost, 2019, due to Hypertensive heart disease. "Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a general term for conditions affecting the heart or blood vessels." (Link) | This is the main measure we use to understand how much of a problem sodium-related causes of burden are in a country. Given this is a public health intervention, it will likely be more cost-effective | 45% |

| Sodium Consumption (Mg/day) | Mg/ day of sodium consumed per country. (link) | This indicator allows us to factor sodium consumption to prioritize countries with higher sodium consumption rates. | 20% |

| Number of relevant policies present (Max 4) | Score constructed from commitments per country, max 4 points, one point each for: • Reformulation (Man/Vol) • FOPL (Man/Vol) • Fiscal • Public food procurement and service (Man/Vol) | This is one way for us to measure neglectedness by investigating the policies a country has introduced. Note this does not reflect how good the country is at actually implementing these. | 10% |

| National policy commitment | Has made a national commitment to sodium reduction. | This is another measure of neglectedness for us to understand whether a country has committed to reducing sodium. Note this could take the form of a vague commitment, so we are uncertain about the value of this indicator. On balance, we expect this to at least reflect which countries are behind on the path to policy introduction. | 5% |

| FSI - Security | 2023 Fragile States Index scores for security-relevant indicators: C1: Security Apparatus C2: Factionalized Elites C3: Group Grievance X1: External Intervention" | We think prioritizing safer countries to work in is best. | 5% |

| Elite Consultation | Average of expert scores for question: When important policy changes are being considered, how wide is the range of consultation at elite levels? 0: No consultation. The leader or a small group (e.g., military council) makes authoritative decisions independently. 1: Very little and narrow. Consultation with only a narrow circle of loyal party/ruling elites. 2: Consultation includes the former plus a larger group loyal to the government, such as the ruling party’s or parties’ local executives and/or women, youth, and other branches. 3: Consultation includes the former plus leaders of other parties. 4: Consultation includes the former plus a select range of society/labor/business representatives. 5: Consultation engages elites from all parts of the political spectrum and all politically relevant sectors of society and business. Average for 2020,2021,2022 | This indicator may allow us to prioritize countries where policymaking involves more consultation; this could improve the odds of policy introduction for a non-profit. | 5% |

| Policy Enforcement | Rule of Law index scores related to how good a government is at enforcing laws. | This indicator may allow us to prioritize countries that are better at implementing policies. | 5% |

Table 9: Priority countries to consider

| Voluntary measures | Mandatory measures | ||||||||||||||||

| Country | Sodium Consumption (mg/day) | DALY burden of cardiovascular disease, oer 100,000 population , 2019 | SCS | NPC | R | PFP | FOPL | OINL | MR | MC | DSC | R | PFP | FOPL | OINL | MR | Fiscal |

| Indonesia | 4143 | 6,364 | 3 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Montenegro | 5040 | 11,269 | 3 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Bulgaria | 5087 | 19,258 | 3 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| North Macedonia | 5052 | 11,921 | 2 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Bosnia | 5050 | 9,951 | 2 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Albania | 5054 | 8,134 | 1 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Serbia | 5072 | 11,959 | 3 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Philippines | 4113 | 4,886 | 3 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE |

| Bangladesh | 3497 | 4,692 | 2 | TRUE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| Mauritius | 4254 | 5,761 | 1 | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | TRUE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

Alternative prioritization with HICs

There was some disagreement in the team on whether HICs should be excluded. For instance, we thought that there is generally a higher level of consumer concern about health factors which increases the incentives for sodium reduction, people live longer, and CVD affects people in old age, so the DALY effect would be greater, there is greater evidence of tractability and higher probability of policy change success, and higher government capacity for implementing changes and enforcing policy. These reasons, though debatable, could mean an HIC would be a more attractive target for this work. If HICs are included, the priority country list would be:

- Indonesia.

- Romania.

- Japan.

- Slovakia.

- Montenegro.

- Bulgaria.

- North Macedonia.

- Croatia.

- Bosnia.

- Hungary.

7 Cost-effectiveness analysis

Our cost-effectiveness analysis models the introduction of sodium reformulation in line with WHO recommendations in Indonesia and Georgia (separately).

- We model an advocacy charity with the primary objective of reforming sodium-high foods to a level according to WHO-recommended benchmarks. In our model, the charity conducts formative research and advocacy, with some additional capacity for firm support.

- We model the introduction of food reformulation alone. Given that the evidence for these programs often comes from multi-component interventions with very heterogeneous results, we do not think we can add up the effects of other components onto reformulation, as they cannot be disentangled.

- We think that sodium and blood pressure have a more or less linear relationship. We model sodium reduction to CVD risk directly, given the availability of sources that estimated these effects and the reduction of risk for errors.

- Health effects are discounted by 1.3% year on year. Costs are discounted by 4%. We model the benefits indefinitely but note the discount rate makes it effective ~100 years.

7.1 Effect modeling

| 1 | Reduction in sodium intake: The reduction in sodium intake expected, based on weighted average several studies reporting sodium intake effects, and discounted for internal and external validity. |

| 2 | Effects of sodium intake reduction on CVD risk: A function of the DALYs lost per person due to stroke, ischemic heart disease, and hypertensive heart disease; and the evidence from He and MacGregor’s meta-analysis (2011) adjusted for internal validity and to the reduction expected in step (1). |

| 3 | The economic costs of implementing reformulation, expressed as a disbenefit to all individuals. |

| 4 | Other factors, including

|

7.2 Cost modeling

| 1 | The expected staffing costs for the organization during advocacy and for some years after the introduction of the policy. |

| 2 | Expected staffing costs for technical assistance, based on the number of large food firms in the countries and salaries. These are the only costs we consider as part of the technical assistance modeling. |

| 3 | Other factors, including

|

7.3 Results

Our model

We ran our model of the intervention through a Monte Carlo simulation (see here). Under our model parameters and choices, this intervention may avert

- In Indonesia, 866 DALYs for every USD 1,000 spent (90% CI -4 - 3045). Corresponding to about a USD 1 per DALY (95% CI inv. CI 0 - 1000).

- In Georgia, 13.8 DALYs for every USD 1,000 spent (95% Confidence Interval 0.3 - 47.5). Corresponding to $72 per DALY (95% CI inv 21 - 3333).

The results are most sensitive to some of the following parameters:

- The expected reduction in CVD risk from reducing sodium intake

- The magnitude of the reduction in sodium intake arising from the intervention

- The probability of advocacy success

- Number of industry players reached with assistance

As always, results for CEAs are hugely reliant on how and why we make confident modeling choices. Table 10 shows different modeling choices and how we expect they have influenced the results.

Table 10: CEA considerations

| Reasons this intervention could be more cost-effective than modeled, all else equal. | Reasons this intervention could be less cost-effective than modeled, all else equal. |

|---|---|

|

|

Other CEAs

Table 11 presents results from other models we have found in the literature.

Table 11: CEAs in the literature

| Source | Approach / Context / Intervention | Results |

| Nghiem et al. (2015) | New Zealand, over 35s. Markov macrosimulation. Assortment of options. | “Even larger health gains came from the more theoretical options of a “sinking lid” on the amount of food salt released to the national market to achieve an average adult intake of 2300 mg sodium/day (211,000 QALYs gained, 95% uncertainty interval: 170,000 – 255,000), and from a salt tax. All the interventions produced net cost savings (except counseling – albeit still cost-effective). Cost savings were especially large with the sinking lid (NZ$ 1.1 billion, US$ 0.7 billion). Also, the salt tax would raise revenue (up to NZ$ 452 million/year). Health gain per person was greater for Māori (indigenous population) men and women compared to non-Māori.” |

| Webb et al. (2017) | “A “soft regulation” national policy that combines targeted industry agreements, government monitoring, and public education to reduce population sodium intake, modeled on the recent successful UK program”

| Cost-effectiveness (Int. $ / DALY averted) of a policy reducing sodium intake by 10% over ten years. Indonesia: USD 71 / DALY Weighted average for the world: USD 204 / DALY, for upper middle-income countries: USD 146 / DALY, lower-middle-income countries: USD 111 / DALY, low-income countries: USD 215 / DALY. |

| Taylor et al. (2021) | “The three salt substitution strategies included voluntary, subsidized and regulatory approaches targeting salt, fish sauce and bot canh products. Costs were modeled using the WHO-CHOICE methodology. A Markov cohort model was developed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of each strategy versus no intervention from the government perspective” | “The voluntary strategy was least cost-effective (− 3445 ₫ US$ -0.15; 0.009 QALYs gained) followed by the subsidized strategy (− 43,189 ₫ US$ -1.86; 0.022 QALYs gained) and the regulatory strategy delivered the highest cost savings and health gains (− 243,530 ₫ US$ -10.49; 0.074 QALYs gained).” |

| Tan (2023b) | “The core of our research is our highly detailed cost-effectiveness analysis, which aims to calculate a philanthropic cause area's marginal expected value (MEV). MEV = t * Σ(n = p * m * s * c) where t = tractability, or proportion of problem solved per additional unit of resources spent n = expected benefit/cost p = probability of benefit/cost m = moral weight of benefit/cost accrued per individual s = scale in terms of number of individuals benefited/harmed at any one point in time c = persistence of the benefits/costs” | “Our headline findings are that the MEV of advocacy for top sodium reduction policies to control hypertension is 30,141 DALYs per USD 100,000 committed” |

8 Implementation

This section summarizes our judgments of different implementation aspects a new charity putting this idea into practice may wish to consider.

8.1 What does working on this idea look like?

This is, at its core, an advocacy intervention. The key function founders and core staff will, therefore, fulfill will likely be in networking and lobbying with key stakeholders and decision-makers, such as:

- Ministry of Health officials and other public health authorities.

- Political leaders, such as members of legislative chambers, ministers, opposition and government leaders, etc.

- Industry players, such as food producers and food industry lobbying organizations.

- Researchers and research bodies.

- Other advocacy organizations and professional associations (e.g., cardiologists).

As noted in section 3, depending on the chosen components and country needs, a new organization may play additional functions, such as

- Research and monitoring (by setting up lab testing capacity or partnering with laboratories).

- Technical capacity strengthening (potentially by hiring specialist staff or upskilling). Mostly, this will revolve around providing the right advice and guidance on how to reformulate food products to contain less salt while still retaining a good taste for food producers. We have been able to find a few pieces of guidance online and think food production specialist consultants should be able to support inexperienced food production firms with this easily.

8.2 Key factors

This section summarizes our concerns (or lack thereof) about different aspects of a new charity putting this idea into practice.

Table 12: Implementation Concerns

| Factor | How concerning is this? |

| Talent | Low Concern |

| Access to information | Moderate Concern |

| Access to relevant stakeholders | High Concern |

| Feedback loops | Moderate Concern |

| Funding | Low Concern |

| Scale of the problem | Low Concern |

| Neglectedness | Low-Moderate Concern |