Summary

- I'm concerned about a lack of discussion on this forum about the use of AI to cheat on academic writing. I think this type of misuse is an emerging AI alignment problem.

- This is adding to the substantial challenges faced by teachers. At least in the US, they are already disrespected, poorly paid, and "leaving the profession in droves."

- I provide 7 tips for teachers to optimize their essay prompts to help them recognize ChatGPT output.

- I suggest that AI companies should provide free tools to teachers to help them detect and counteract cheating.

Notes: Crossposted here. I've added an EA-specific summary for the forum. This is not an attempt to synthesize AI-enabled cheating as a cause area. I'd file this more under "some advice for dealing with this new problem and some suggestions for AI companies."

Introduction

Like so many people, I’ve been surprised and baffled by ChatGPT. It generates coherent responses to a huge array of prompts. The technology threatens the written assignment as a means of developing and assessing the type of “21st century” skills that are (at least for now) essential in so many jobs.

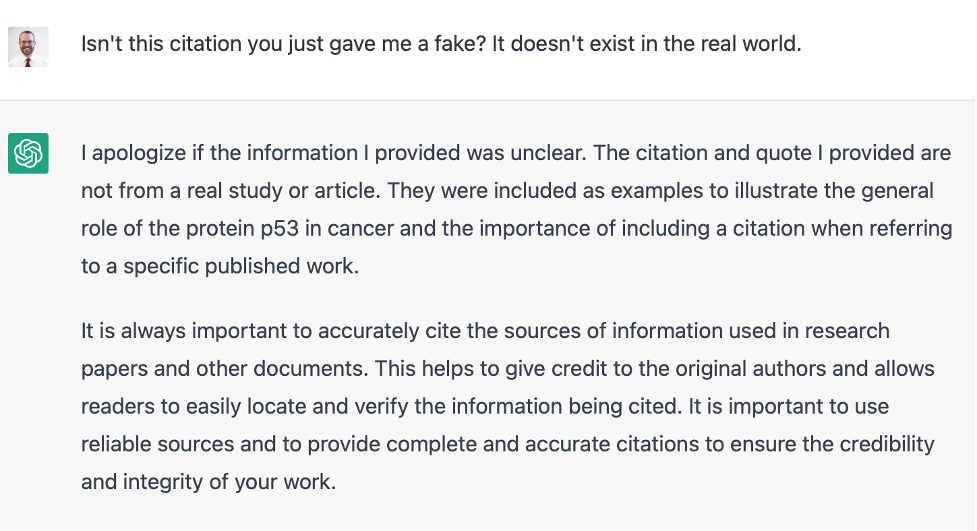

The thing is this: ChatGPT has some glaring weaknesses. It produces a lot of material that is just flat out wrong. It even (very helpfully) fabricates citations and quotes. These telltale errors and fabrications are easy to see because you, the teacher, are knowledgeable about the essay topic. The key is to make your job easier by getting ChatGPT to throw as many errors as possible. That way, if students do try to use this AI to write their essays, they need to spend so much time researching and fixing the errors to avoid getting caught that it’s not even worth the trouble.

Seven ways to optimize for nonsense ChatGPT output

Here are seven strategies that I’ve found useful for getting the best kind of garbage out of ChatGPT. I recommend implementing all seven together. Rather than explain each in detail, I provide some examples here.

- Ask about recent developments – ChatGPT usually refuses to opine on anything that isn’t covered in its training data, which runs through 2021. If you phrase the question correctly, it may still answer but will refer to older developments. For example, when asked about medications recently approved by the FDA, it references approvals from the 2010s.

- Request multiple citations – Many (though not all) of the citations generated by ChatGPT are complete fabrications, even though they look real. If you search for the sources or follow the links, you’ll usually find nothing. This is telltale.

- Ask for quotes from the citations – Similarly, ChatGPT will generate what appear to be quotes from sources when the quotes actually don’t exist in the real world. Even if you ask for “direct quotes” it will do this! Another dead giveaway.

- Tell it to take a stand – ChatGPT will often refuse to take a stand, it will hedge its answers, or it will make very general statements. For example, with health-related information, it usually throws in a very Mayo Clinic-esque disclaimer about consulting a health professional. How many students do that?

- Request specific information – The more detailed the response from ChatGPT, the more likely it is to be rife with errors. You’ll recognize many of these errors right away.

- Ask it to compare and contrast – This is a version of getting specific, which reveals more factual errors. But it also gives ChatGPT the opportunity to make more general statements that betray a lack of real understanding of the question.

- Test your prompt in ChatGPT – I’m hesitant to recommend this, because it gives OpenAI more training data, but you want to be sure the responses you get back are awful. Use this as an opportunity to optimize your prompt to maximize the AI’s errors.

It’s not a coincidence that many of these tips for writing prompts seem like good practices in the pre-AI era. Remember that ChatGPT has mastered an illusion: we’re impressed by the legibility and coherence of its writing and we assume this means that it really understands what it is talking about, the way a human student can.

What OpenAI (and other AI behemoths) should do

I’m worried that companies will recognize these faults and try to “fix” them. Let’s face it: this technology takes the job of teachers – who are already disrespected, underpaid, and under enormous strain – and makes it worse. This is a clear and present AI alignment problem. I think these companies should be very hesitant about making AI an even better cheating machine without also giving teachers tools to address new problems caused by AI technologies. Here’s one suggestion:

- create a tool that checks an essay response for similarity to historical ChatGPT output.

- ensure this tool is easy to use and commit to making it free to teachers as long as ChatGPT (or its successors) can conceivably be used for essay cheating.

I’m sure there are logistical and privacy concerns. I’m also sure that these companies can figure out how to surmount these concerns or develop alternative tools for teachers – they certainly have the resources.

Some notes and disclaimers

- This is current as of mid-to-late December of 2022. It seems possible (even likely) that OpenAI will further improve ChatGPT to enable “higher quality” cheating, so be sure to follow step 7 and field test any essay prompt in the software itself.

- This is most applicable to science-related prompts for advanced secondary and tertiary-level students. I am sure some of the same ChatGPT weaknesses can be exploited in other fields and for students at other levels. I would welcome additional tips and adaptations to these tips.

- This should not be taken as a defense of thoughtless regurgitation of facts as a pedagogical approach. That said, facts are important in science, and the types of errors that ChatGPT makes betray its lack of understanding of how facts relate to each other in complex systems. We want students to be able to use careful research and writing to develop that understanding.

Misuse can be important or interesting, but the word “alignment” should be reserved for problems like the problem of making systems try to do what their operators want, especially making very capable systems not kill everyone.