This report was conducted within the pilot for Charity Entrepreneurship’s Research Training Program in the fall of 2023 and took around eighty hours to complete (roughly translating into two weeks of work). Please interpret the confidence of the conclusions of this report with those points in mind.

We are grateful to the organisations who took the time to engage with this research. Being transparent about your own monitoring, evaluation and cost-effectiveness is hard and we applaud all efforts that try to share this data openly with people trying to understand the impact that the organisation has.

For questions about the structure of the report, please reach out to Leonie Falk at leonie@charityentrepreneurship.com. For questions about the content of this research, please contact Moritz Stumpe at moritz@animaladvocacyafrica.org.

The full report can also be accessed as PDF here.

Executive summary

This executive summary synthesises the findings from our in-depth review of Animal Advocacy Careers (AAC), focusing on their different programmes, effectiveness, and areas for improvement.

AAC plays a critical role in the animal advocacy movement by addressing talent bottlenecks. Organisations within the movement highly value the access to qualified candidates, a gap AAC aims to fill through its various services, including career advice, workshops, and job boards.

AAC's theory of change (ToC) is robust and predominantly supported by evidence. It suggests a positive impact on animal welfare through its programmes. However, this review identifies key uncertainties that need addressing. Firstly, the potential negative externalities of AAC's services, such as inadvertently directing individuals towards less optimal career paths or inducing anxiety over career choices, require careful monitoring and research. Secondly, the efficacy of AAC's recruitment services, despite high demand, remains a point of scepticism. These services need close evaluation to determine their future role in AAC's portfolio.

A standout aspect of AAC's methodology is the innovative use of Importance- and Counterfactual-Adjusted Placements (ICAPs) for evaluating its impact. This approach indicates a positive cost-benefit ratio, with AAC generating approximately USD 2.6 for every dollar spent. However, this metric's robustness could be further enhanced. Recommendations include adopting systematic approaches such as confidence intervals and developing a detailed rubric for counterfactual judgement. We also recommend that AAC collect stronger data for backing some of the assumptions in its monetary valuation of one ICAP. Such refinements would increase the accuracy and transparency of AAC's impact assessments.

Regarding organisational health, AAC demonstrates stability and efficiency with no major concerns. Their transparency and leadership's clear future vision are commendable. However, some improvements can be made to further strengthen their organisational framework.

Finally, we advise AAC to try to diversify their funding sources. Their current primary reliance on a few large donors within the Effective Altruism community might present a risk.

In summary, AAC stands out as a valuable contributor to the animal advocacy movement. It effectively addresses crucial talent needs and demonstrates impactful programme execution. However, there is room for enhancement in its monitoring systems, recruitment service, and funding diversification. Overall, our assessment of AAC is positive, with targeted recommendations aimed at maximising its impact and ensuring its long-term success in the movement.

1 Background

“Animal Advocacy Careers (AAC) was founded in late 2019 through Charity Entrepreneurship’s incubation program, with the goal to attract top talent to the [effective animal advocacy] movement and empower them to make a real impact.” (Animal Advocacy Careers, n.d.-a)

AAC is a typical example of a capacity-building organisation, aiming to reduce the unnecessary suffering and improve the welfare of animals by supporting those who themselves work on this issue directly.

In this report we aim to assess AAC’s success and effectiveness in achieving this goal. To start with, in this section, we will first examine whether AAC is addressing an important problem within the cause area of animal welfare (1.1), and then describe AAC’s different programmes (1.2). This builds the foundation for the following sections, where we then evaluate AAC’s work.

1.1 Needs assessment

On their “About” page, AAC writes:

“The animal advocacy movement is desperately in need of passionate, talented professionals to help fast forward the end of animal suffering. Recruiting the perfect fit for a role can be an arduous process, with organisations often spending months searching for the ideal candidate for some roles.” (Animal Advocacy Careers, n.d.-a)

AAC also writes that talent bottlenecks can have many detrimental effects on the movement. Among others, they can slow down the growth of organisations or lead to less effective work due to lower quality hires (Animal Advocacy Careers, n.d.-a). In this section, we aim to evaluate these claims, understanding the problem that AAC is trying to solve and how important it is.

Charity Entrepreneurship incubation

The logical starting point for our assessment is the research done by Charity Entrepreneurship (CE) which led to the creation of AAC. In the publication of their top charity ideas for 2019, CE explains that finding the right staff is a frequent challenge for animal advocacy organisations (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2019). In a survey of leaders and researchers within the movement, they found some excitement around the possibility of increasing the talent pool in the animal advocacy movement, especially in large neglected countries like China or India. CE estimated this to be a tricky problem to work on, but one that could be of very high impact. (Savoie, 2018) Due to the large uncertainties involved and the lack of systematic research that has been done on this issue, CE suggested that ways of improving hiring and training within the movement should be investigated and tested further. This research was supposed to be done by a new organisation focused specifically on animal advocacy careers. Apart from research, this new organisation could act as a central contact point for talent and career topics. (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2019)

CE recommended that the organisation would conduct small experiments in three different areas, trying to understand what is the most effective approach for filling talent gaps:

- Finding (e.g., finding new applicants through headhunting or outreach),

- Training (e.g., training possible candidates in management skills that are highly lacking in the movement), and

- Sorting (e.g., matching people with fitting roles). (Charity Entrepreneurship, 2019)

Animal Advocacy Careers’ own research

Following these recommendations and the incubation by CE, AAC started conducting research into different potential priority areas and published the results from a variety of research projects on the blog on their website in late 2020. These findings were supposed to help them in their strategic prioritisation and the design of their services, but could also be useful to others. The following is an overview of different topics they researched:

| Topic | Source |

|---|---|

| The characteristics of effective training programmes | Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020a |

| The effectiveness of management and leadership training | Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020b |

| The characteristics of good management | Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020c |

| A brief overview of recruitment and retention research | Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020d |

| A brief overview of hiring and turnover costs research | Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020e |

We do not describe the findings of these research projects here, as they do not seem relevant for our needs assessment.

However, one research project conducted by AAC is highly relevant here. In 2020, AAC published the results of surveys they had done with HR experts and directors of nine animal advocacy organisations, trying to understand their biggest talent and hiring bottlenecks and how they could be addressed (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020f). Crucially, when it comes to the importance of an influx of stronger talent into the movement, AAC reports the following finding:

“All organisations unanimously agreed that if their quality-adjusted pool of applicants doubled for the next 3 years (vs staying constant), this would contribute more to enable them to do good as an organisation than a doubling of their funding over the same period. The majority agreed they would be able to double the amount of good but some more cautiously estimated 25% more good.” (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2020f)

Following these initial, brief surveys, AAC ran an enhanced version of this research, conducting two surveys with different sets of participants (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2021):

- Leadership and hiring managers at effective animal advocacy nonprofits:

AAC reached out to 56 organisations, achieving a 70% response rate with 39 distinct organisations participating. The survey was designed to gather a single representative response from each organisation, specifically targeting individuals in top-level leadership positions such as CEO, ED, COO, VP, or those involved in hiring or human resources. The majority of respondents, with the exception of three, held leadership roles within their respective organisations. Further information on the kinds of organisations that took part in the surveys (e.g., their geographic location, their size, or the focus of their work) can be found in AAC’s report. - Researchers, grant-makers, plus others working on “meta” and movement-building services for the movement:

For this survey, AAC adopted a less formal approach in terms of inclusion or exclusion criteria, reaching out to organisations involved in research, grant-making, and other movement-building services, where they anticipated valuable input. They did not imply a need for the responses to be representative of the entire organisation, but in most instances, they still requested only one response per organisation to minimise the time required for completing the survey. They contacted 21 organisations and received 16 responses from 13 different organisations, resulting in a 62% response rate.

Below, we summarise the findings from these surveys in depth, as they offer crucial insights into the talent needs of the movement and form the basis for AAC’s strategic prioritisation.

AAC’s surveys confirmed that the availability of high quality applicants for paid roles was a highly important bottleneck, and that this finding was consistent across regions. Lack of funding was the key bottleneck in both surveys, with lack of (qualified and capable) applicants for paid roles not far behind. Other highly important bottlenecks were unfavourable attitudes from targets of advocacy and a lack of public awareness of the organisations’ work. The ranking of items from most to least limiting was similar for both the Global North and South. The lack of qualified and capable applicants was particularly highly rated as a bottleneck in Asia and for corporate/producer welfare campaigns. (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2021)

In line with their previous survey, AAC also identified that a high threshold is required for individuals to help animals more by choosing careers focused on donating money to nonprofits rather than dedicating time and labour directly, even for roles which are not necessarily the hardest to hire for. They note that one “could interpret these results as suggesting that organisations would rather receive one additional very-high quality applicant for the roles that are hardest to hire for than receive $25,000 or more (each year for the length of time that the applicant might otherwise have been employed for)” (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2021). However, this finding should not be taken extremely strongly due to concerns about reasoning and interpretation of the corresponding survey question. The finding is also somewhat at odds with AAC’s other finding that funding is the biggest bottleneck for the organisations in their survey.

Nevertheless, the report provides moderately strong evidence that the availability of high quality applicants for paid roles is a major concern for animal advocacy organisations.

More specifically, organisations that participated in the survey faced the most substantial hiring difficulties for roles focusing on leadership or senior management, fundraising or development, and government, policy, lobbying, or legal tasks. However, on average, this difficulty peaked at 3.6, where 3 represented somewhat difficult and 5 represented very much. There were generally higher difficulties in meeting talent bottlenecks in the Global South and Asia, compared to the Global North and not Asia. There were few differences by role type in terms of retaining staff, though fundraising and development stood out as slightly more difficult than average. Retention challenges were considerably lower for each position than hiring challenges, suggesting that responders found hiring a larger issue than retaining talent. To address existing talent bottlenecks, respondents commonly suggested headhunting and training for current staff as solutions. (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2021)

Continuing their efforts of identifying the crucial talent bottlenecks in the movement, AAC published further research into the hiring challenges faced by organisations in 2022. This most recent survey was less extensive than the previous one explained above, as AAC did not expect things to have changed drastically over a relatively short period of time and aimed to reduce the effort for participating organisations. (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2022) The key findings are thus only summarised shortly here as follows:

“As with some of our previous evidence, this survey suggests that senior leadership roles are most difficult to hire for, followed by fundraising and development roles. There were some results that differed from our previous research, such as an absence of evidence that “IT or software” roles are particularly difficult to hire for.

We also asked some questions about what might make candidates for roles seem more or less promising. One surprising finding here was that having an additional year of volunteering with effective animal advocacy nonprofits using relevant professional expertise was evaluated more favourably than having an additional year of somewhat relevant paid experience.” (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2022)

Overall, the evidence from AAC’s own research suggests that talent is a major bottleneck for animal advocacy organisations, specifically in fundraising, leadership, management, and development. While funding was identified as the largest bottleneck for organisations, increased fundraising talent may go some way towards addressing this.

Further external evidence

Apart from the research conducted by AAC themselves and their ‘parent organisation’ CE, we also have to investigate external evidence to understand whether the problem that AAC is trying to address is really as important as they claim it is.

On their website, Animal Advocacy Careers (n.d.-a) make the case that capacity building, the area of work which AAC’s services belong to, is relatively neglected in the effective animal advocacy movement. First, they quote a study from Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) from 2018 to highlight that capacity building receives only an estimated 2.5% of all resources spent by the U.S. farmed animal movement (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2018). Second, they link to an EA Forum post by their co-founder Jamie Harris (2019), highlighting that there are strong movement building initiatives in Effective Altruism generally, but that these tend to neglect animal welfare as a cause area and focus instead on more long-termist objectives. This provides some evidence that addressing talent bottlenecks might be a neglected issue, just as other capacity and movement building activities.

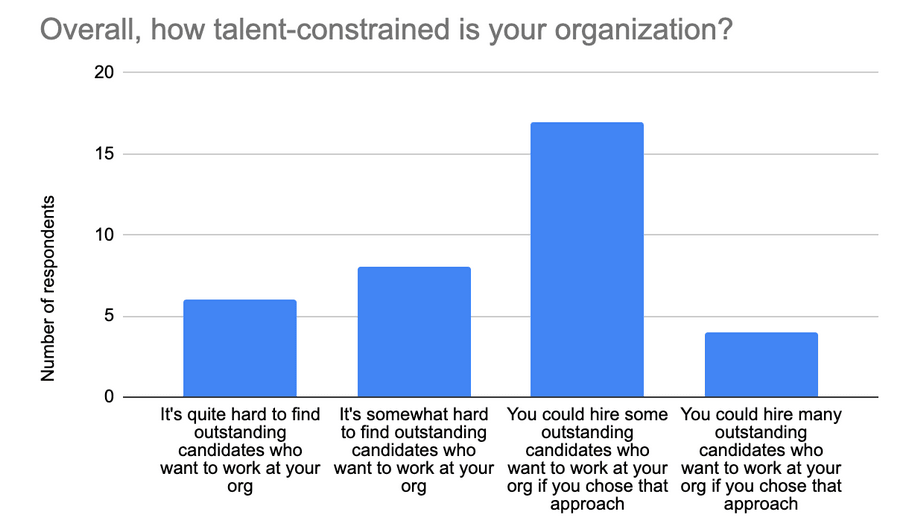

Rethink Priorities seems to corroborate the view that talent constraints are a high priority issue in their 2023 survey of 35 key decision-makers in the animal advocacy community. They find that the most lacking are experts on the developing world or specific neglected but populous countries, fundraisers, and government and policy and/or lobbying experts. However, as shown in the graph below, they also report that the majority of respondents does not find it either ‘quite’ or ‘somewhat’ hard to find outstanding candidates who want to work at their organisation. (Rethink Priorities, 2023)

The share of respondents who had indicated that it is hard to find outstanding candidates was higher in the previous year’s survey (Rethink Priorities, 2022). This provides some evidence that talent gaps might be declining. This could be a result of AAC’s work on filling talent gaps, but it is hard to establish a causal effect here.

Overall, the contrary evidence cited is not strong enough for us to suggest that talent gaps are not still a major bottleneck for the animal advocacy movement. The bulk of the evidence suggests that AAC’s focus area of improving the talent base within the movement is an important problem to work on. However, Rethink Priorities’ findings highlight the need for continuously monitoring this issue, understanding whether AAC might hit diminishing returns and the movement might experience a talent overhang (compared to other scarce resources) at some time in the future. There is a possibility that AAC’s services will be less needed in the future.

This view is supported by the fact that a variety of capacity-building initiatives have emerged within the movement over the last years. Organisations like the Center for Effective Vegan Advocacy, ProVeg, Scarlet Spark or The Mission Motor run courses, trainings, accelerators, and incubators, or provide mentoring and consulting. Other organisations focus on building the capacity of the movement in certain geographic areas, like Animal Advocacy Africa or Animal Alliance Asia. Still others specialise in careers and talent bottlenecks in the movement-adjacent alternative protein space, like the Good Food Institute (e.g., talent database) and Tälist. This emergence of broader capacity-building services needs to be monitored in order for AAC to coordinate with others and direct its resources towards the most important bottlenecks and most cost-effective solutions. We are not concerned about this though. It is our understanding that AAC is actively coordinating with other actors like the ones mentioned above to make sure that there is no duplication of efforts and the most important needs of the movement are addressed. The fact that AAC played an important role in the initiation of two of the organisations mentioned above strongly supports this view.

Summary

Overall, we find that talent indeed seems to be a major bottleneck in the movement. While funding seems to be an even greater need for the movement, organisations are still willing to trade off significant amounts of money for access to better candidates. AAC is thus addressing an important problem. However, it is important to monitor this need over the next few years, as talent gaps are gradually being filled and other capacity-building initiatives emerge.

1.2 Programme description

AAC works to empower animal advocates and organisations who themselves work on improving welfare directly. Their primary pathway to achieving this is through strengthening the talent pool available to animal advocacy organisations. Apart from that, as secondary streams towards impact, AAC also supports organisations in their hiring practices and aims to strengthen the wider ecosystem of farmed animal advocacy (i.e., by increasing donations to the movement and supporting the creation of new organisations).

In order to achieve their goal, AAC is running a variety of programmes. In this section, we provide an overview of these programmes, using publicly available information from AAC’s website and internal descriptions that AAC has made available to us. We therefore do not provide sources below, except for specific quotes or examples. We only include programmes that are either still active, have been active until recently, or still have relevance for AAC’s current activities. For instance, AAC’s management and leadership training is not included here, as it was suspended years ago and is not relevant anymore.

Career advice resources

AAC is providing career advice to individuals that are interested in contributing to the movement by publishing freely available content on their website. They showcase a wide variety of resources that can help people create a strong career in animal advocacy. On the one hand, they write and publish their own reports and posts. This includes, among others, their skill profiles (here), an “Essential Guide for Animal Advocacy” (here), a series of animal advocate profiles (see for example here), a series of posts about career paths (e.g., here and here), or explorations of certain specific ideas (see for example here). On the other hand, they compile other/external helpful and relevant resources here.

Earning to give

A fairly recent addition is AAC’s programme on earning to give. Given that there is a limited number of roles available in the movement and not everyone will be a good fit for those or be willing to completely change career paths, AAC has decided to more actively encourage people to take the Giving What We Can pledge or otherwise make significant donations to effective animal advocacy organisations. This programme aims to contribute to a more diversified and robust funding ecosystem for the movement. In order to fulfil this aim, AAC develops website content and marketing materials to spread their message, hoping for this to be a potentially low-cost and high-return way of bringing value to the movement. As such, this programme is highly related to the career advice resources mentioned above and we do not include it separately in our theory of change in section 2.

Career advice calls

AAC is also giving career advice in direct calls with people, supporting them in their career planning and concrete next steps. While the first stream of career advice above provides generic information and input, this second stream is more personalised and targeted. This service is aimed at only very promising individuals due to the larger time investment needed to conduct these calls. They have trialled both 1-1 and group formats over the last years, focusing more on the latter lately in order to improve the cost-effectiveness of this service.

Online course

AAC is running a free, self-paced “Introduction to Animal Advocacy” online course. The course is based on the research and resources described above in the first stream of AAC’s career advice activities and provides a relatively basic introduction to a potentially high-impact career within the farmed animal advocacy movement. With an expected time commitment of roughly 9-18 hours participants are supposed to discover relevant career options, design their career plans, and define actionable next steps. Participants do not have to do the full course, but can pick and choose sessions. Successful participants receive a certificate and are invited to be included in AAC’s talent database which is shared with hiring managers (see below). This is a scalable programme that requires much less staff time per person than personalised career advice.

Job board

AAC hosts a job board on its website, highlighting roles at impact-focused animal nonprofits and key details such as location and application deadline. The board is updated weekly based on AAC’s active research and suggestions by others. Because of AAC’s primary aim of connecting individuals with roles directly within the animal advocacy organisations, the board does not include potentially high-impact roles in academia, government, food companies, or similar. For such roles, AAC refers to other resources (e.g. skill profiles, other job boards). Related to this job board is an AAC mailing list that informs interested people directly about current relevant opportunities.

Fundraising work placement

AAC has run a fundraising work placement programme for the first time in 2022. The programme was informed by previous AAC research on the needs and bottlenecks in the movement (Animal Advocacy Careers, 2022) and aimed to place promising individuals into remote, paid, temporary fundraising positions at effective animal advocacy nonprofits. Participating individuals first did independent learning with AAC’s support for 10-30 hours and were connected with other fundraisers and advocates, before being matched with a partner organisation. They were compensated for the full process. They then moved on to work full- or part-time at the partner organisation for three months, aiming to fill common fundraising bottlenecks and thereby increase the organisation’s impact. Participants were supposed to develop important skills, make connections, and build experience, potentially getting hired by their organisation for a job after the temporary placement.

Recruitment

AAC has experimented with different direct recruitment services. At the beginning, AAC directly supported organisations with recruitment for leadership, management, and fundraising roles, as these were harder to fill than others and could significantly affect the organisations’ impact. In addition, AAC occasionally offered guidance on organisations’ hiring and recruitment practices, either as a substitute for or in addition to their primary search efforts. However, this form of recruitment service was discontinued based on internal evaluation results (see section 3.1.2.2). It is therefore also not included in the theory of change we outline in section 2.

Top candidate database

Instead, AAC decided to trial a new version of recruitment service from October 2022 onwards: their top candidate database. This database includes candidates for which participating organisations report that they have been unsuccessful in an application with them but seem promising. The database is privately shared with partner organisations to consider in their hiring processes. The aim is to avoid the drain of talent from the movement and increase access to strong candidates for animal advocacy organisations.

Inclusive hiring skills workshops

In collaboration with Tania Luna, AAC has run a series of three workshops for hiring professionals (e.g., HR managers, founders) of roughly 90 minutes each. Originally, tickets had to be bought for attending these workshops (at USD 249 for all three workshops as a bundle), but the sessions are now freely available on AAC’s website based on email signup. The content focuses on strategies for successful talent acquisition and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices, aiming to build better teams at animal advocacy organisations. Participants are supplied with tools, skills, insights, and a community of like minded people. The idea is nicely summarised by this quote from AAC’s website: “Let’s come together to make the world a better place for animals by making the workplace better for people” (Animal Advocacy Careers, n.d.-c). This programme is different from AAC’s other work, as it focuses on hiring practices instead of the enhanced access to strong candidates. It therefore also follows a different path to impact in the theory of change that we outline in section 2.

Summary

In sum, we have identified the following services that seem relevant for AAC’s theory of change: career advice calls, career advice resources, fundraising work placement, inclusive hiring skills workshops, job board, online course, and top candidate database. Here we exclude the earning to give and recruitment programmes described above, since the former is subsumed under the career advice resources and the latter was suspended in 2022.

2 Theory of change

2.1 Causal chain

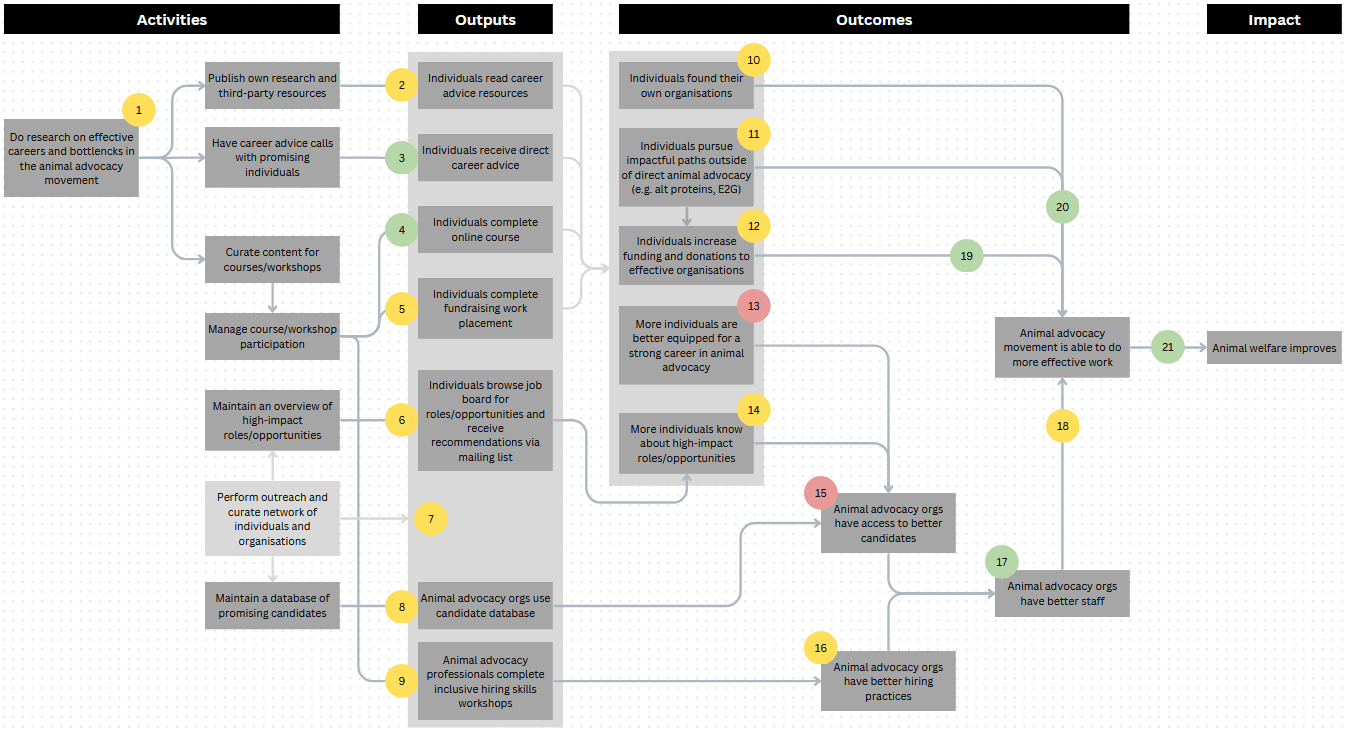

In order to understand exactly how AAC aims to tackle the need described in section 1.1 with the programmes described in section 1.2, we have constructed a theory of change (ToC) for their work. The ToC outlines the different steps that need to hold true in order for AAC to have the desired positive effect on animal welfare.

In constructing this ToC, we first aimed to take an unbiased outside view, trying to understand the different pillars of AAC’s work and how they fit together to create positive change. We actively refrained from looking at existing ToCs about AAC’s work at this first stage. Once we felt comfortable about our ToC, we consulted existing ToCs (a simple one from AAC’s website, another very simple one from Animal Charity Evaluators, and a more comprehensive internal one provided to us privately by AAC) in order to see whether we had missed any crucial considerations or had made any mistakes. We also consulted AAC staff for feedback on some open questions. We found that the ToC we had constructed was reasonable and did not include major mistakes. However, we detected some minor omissions that we then added to our conceptualisation (e.g. the potential for AAC to lead people to impactful paths outside of the narrow animal advocacy movement that can help improve animal welfare, like earning to give or working on alternative proteins).

The full visualisation that resulted from this process is shown in the picture below and is available with better visibility here. The outputs are the seven programmes identified in section 1.2. The numbers indicate assumptions that need to hold for the different steps to work out as intended. Their colours represent the level of uncertainty for this specific assumption/part of the ToC prior to a deeper evidence review, from red (high), to yellow (medium), and green (low).

2.2 Outlining assumptions and levels of uncertainty

In this section we outline the assumptions that we identified in the ToC shown above, highlighting some preliminary thoughts and considerations, before we try to resolve as many uncertainties as possible via our evidence review in section 3.

1. AAC can find out which are the most important bottlenecks and most promising careers in animal advocacy.

This assumption seems extremely important for AAC’s ToC. If they cannot find out what the most important bottlenecks and most promising careers in animal advocacy are, they cannot give helpful advice. Their impact would then mostly be in helping people to find opportunities/roles (see assumption #6), giving animal advocacy organisations access to a candidate database (see assumption #8), and improving the hiring skills of these organisations (see assumption #9). Our initial assumption is that AAC’s biggest impact comes from skill-building and providing research and resources to interested individuals (assumption #13). We therefore think that AAC would be left with only a fraction of its impact, if assumption #1 broke down and all of the tightly related services (career advice, online course, and fundraising work placement) could not positively impact people’s career trajectory.

Overall, it seems plausible that AAC can arrive at findings that marginally improve career decisions. Our needs assessment in section 1.1 has already described some research that seems relevant in this regard. It is important for AAC to continuously monitor this though, which we understand they do.

2. AAC is able to publish research and resources that are interesting/relevant to a wide-enough target audience.

It seems plausible that content might not be used/consumed by many people. Only if the resources are used can they have an impact on people’s careers.

However, the assumption is not absolutely necessary to hold for AAC to have the ultimate impact they aim for, since there are other programmes / parallel paths. If we find that the resources are not widely used, AAC might consider shutting down this part of their activities. This seems unlikely to be a good course of action though, since the underlying research and resources are important for other parts of their works as well (direct career advice, etc.). Even if this public part of AAC’s research would not provide much direct external value, the research should generate a solid foundation for their other services.

3. AAC is able to give direct career advice that is interesting/relevant to a wide-enough target audience.

If the direct career advice service is not frequently requested/used, this part of AAC’s services could be suspended, as it is not crucial for other parts of the ToC to hold.

Our prior familiarity with AAC’s work suggests that this is an attractive service for people and is well-received.

4. AAC is able to run an online course that is interesting/relevant to a wide-enough target audience.

Our initial perspective on this assumption is the same as for assumption #3.

5. AAC is able to run a fundraising work placement programme that is interesting/relevant to a wide-enough target audience.

Our initial perspective on this assumption is similar as for assumptions #3 and 4.

However, this programme was only run in 2022 and seems not to have been repeated so far due to funding constraints (Charity Entrepreneurship, n.d.). This might imply that funders did not judge this programme as a good use of resources. Whether this is true or whether there are other reasons for the programme having only been run once is an important aspect to check in our review.

6. AAC is able to curate an overview of opportunities/roles that is interesting/relevant to a wide-enough target audience.

This is an important assumption that needs to hold in order for AAC to be able to help individuals find high-impact roles and opportunities. In theory, AAC could also suspend this service and only focus on other services. As described under assumption #1, we assume that AAC’s largest impact comes from equipping people with the advice and skills they need to have a strong career in animal advocacy (assumption #13). This could also be done without facilitating the search for roles/opportunities. In practice however, we think that there is a strong interplay between equipping people with advice and skills on the one hand and showcasing potential roles and opportunities on the other hand. It is thus important for this assumption to hold in order for AAC to achieve its full impact on talent availability in the animal advocacy movement.

It seems fairly straightforward to curate an overview of opportunities and roles. Our prior familiarity with AAC’s work suggests that this is an attractive service for people and is well-received.

7. AAC is able to do effective outreach and build a strong network of individuals and organisations that want to use their services.

Strong marketing, outreach, and networking is an important supporting factor for all of AAC’s services. On the one hand, it helps AAC to drive more individuals towards their services, thereby increasing the value of their services to the movement. On the other hand, a strong network of partner organisations also helps to enhance AAC’s offering and make it more attractive to individuals. This assumption is thus an important one for AAC to have a strong impact.

Our prior familiarity with AAC’s work suggests that they have marketed their services well and dispose of a good network of individuals and organisations.

8. AAC is able to maintain a candidate database that is interesting/relevant to animal advocacy organisations.

Our initial perspective on this assumption is similar as for assumptions #3 and 4.

If the candidate database is not frequently used, this part of AAC’s services could be suspended, as it is not crucial for other parts of the ToC to hold. We do not know how well-received the service is though.

9. AAC is able to run inclusive hiring skills workshops that are interesting/relevant to animal advocacy professionals.

This part of the ToC seems fairly detached from AAC’s other streams of impact. It should constitute a very minor part of their overall impact. As such, this assumption is not necessary to hold. We still decided to include this aspect of AAC’s work in order to get a comprehensive picture of all the ways in which they aim to improve the lives of animals.

If the workshops are not frequently requested/used, this part of AAC’s services could be suspended, as it is not crucial for other parts of the ToC to hold. We do not know how well-received the workshops are. The fact that they are now offered for free, while they previously had a significant price tag, suggests that demand was not too high.

10. Consumers of AAC’s services decide to found their own organisations.

AAC’s focus seems to be on getting people into roles directly at animal advocacy organisations. However, some people might be influenced by AAC’s career advice to start their own organisation in animal advocacy. Given the large potential value of charity entrepreneurship, the value of this could be significant, even if it only affects a small number of people. We are unsure whether AAC’s work has had any significant effects in this respect so far.

11. Consumers of AAC’s services enhance their career plans and capabilities for work outside of direct animal advocacy that still helps the animal advocacy movement or to improve animal welfare.

Similar to assumption #10, AAC might also influence people to change their career paths into adjacent areas that help animal welfare, like working on alternative proteins or earning to give to animal causes. This should probably not be the main path of AAC’s impact on people’s careers, but it could have significant value and should be considered. In fact, this path might become more relevant now and in the future, as AAC has started a dedicated earning to give programme, as described in section 1.2.

12. Consumers of AAC’s services increase their donations to or otherwise cause counterfactual funding increases for effective animal advocacy organisations.

The earning to give path directly influences people’s donations to effective animal advocacy organisations. However, AAC’s services might also have an effect on the donations of people that are not explicitly choosing a career path focused on earning to give. We are unsure whether AAC’s work has had any significant effects in this respect so far.

In addition, AAC’s fundraising work placement programme directly aimed at strengthening the funding situation for participating organisations.

13. Consumers of AAC’s services enhance their career plans and capabilities for work in direct animal advocacy.

This assumption is crucial to hold for AAC to have its desired ultimate impact, as a lot of their services are geared towards exactly this outcome.

If the programmes are well-designed and well-received, this assumption should be likely to hold as well. We have to look for evidence on how AAC influences people’s career plans and capabilities. In the optimal case, we can break this down by service, to see how much impact each of the different services has.

We also have to consider counterfactuals here, namely what other paths the consumers of AAC’s services would have pursued in the absence of AAC’s services. Overall, the validity of this assumption is crucial for AAC’s overall impact.

14. Consumers of AAC’s services increase their awareness of relevant roles and opportunities.

As written before (see assumption #6), we assume that AAC’s largest impact comes from equipping people with the advice and skills they need to have a strong career in animal advocacy (assumption #13). This could also be done without facilitating the search for roles/opportunities. In practice however, we think that there is a strong interplay between equipping people with advice and skills on the one hand and showcasing potential roles and opportunities on the other hand. It is thus important for this assumption to hold in order for AAC to achieve its full impact on talent availability in the animal advocacy movement.

If the preceding assumptions hold (AAC’s programmes are well-designed and well-received and they are able to curate and distribute relevant opportunities), this assumption should be very likely to hold as well.

15. AAC’s activities cause an influx of more and/or better talent to animal advocacy organisations.

This assumption is crucial to hold, as it arguably describes the key outcome of AAC’s work (based on our understanding and statements made by AAC)..

If the preceding assumptions hold , this assumption should be likely to hold as well. However, since this assumption is so crucial, we have to look for evidence on how AAC’s work influences organisations.

16. AAC’s workshops improve the hiring processes of animal advocacy organisations.

As written before (see assumption #9), this part of the ToC seems fairly detached from AAC’s other streams of impact. It should constitute a very minor part of their overall impact. As such, this assumption is not necessary to hold. We still decided to include this aspect of AAC’s work in order to get a comprehensive picture of all the ways in which they aim to improve the lives of animals.

The impact of workshops on organisations seems uncertain. If workshops do not have an impact on hiring processes, this part of AAC’s services could be suspended, as it is not crucial for other parts of the ToC to hold. We need to evaluate this.

17. Better candidates and hiring processes lead to better staff.

This assumption seems very straightforward and we will not review it in detail here.

18. Better staff allows organisations to do more effective work for animals.

This assumption seems very straightforward.

However, we need to consider here that a lack of talent may not be a main limiting factor for organisations to do more effective work. Instead, they may lack funding or may be inhibited by other factors. Our needs assessment in section 1.1 indeed showed evidence that a lack of funding, unfavourable attitudes from targets, and a lack of public awareness all ranked before a lack of talent when it comes to the most important bottlenecks. However, lack of talent still emerged as a major limiting factor and there is some evidence that organisations prefer talent over donations in certain cases. Overall, this assumption should hold.

19. Increased funding allows organisations to do more effective work for animals.

This assumption seems very straightforward, as our needs assessment in section 1.1 has shown that funding seems to be the major bottleneck for the movement. We will therefore not review this assumption in detail.

20. Career paths outside of existing animal advocacy organisations enhance the movement’s ability to help animals.

This assumption seems very straightforward. If individuals choose to found their own animal advocacy organisation or decide to work in adjacent sectors (i.e. policy, alternative proteins), this should positively influence the movement’s ability to effectively help animals.

21. More effective work for animals improves animal welfare.

This assumption seems true by definition (almost tautological) and we will not review it in detail here.

3 Evidence review

In this section, we use evidence to inform our view of the validity of the different steps and assumptions in the ToC described in section 2. We first look at evidence collected by AAC themselves in section 3.1, aiming to give an overview of AAC’s monitoring and evaluation (M&E) efforts, explain what we can learn from them, and make recommendations about improvements. We then additionally consult external evidence in section 3.2, in order to get a broader understanding of AAC’s streams of work. In section 3.3, we summarise how this analysis of internal and external data updates our view on AAC’s ToC and the key steps and assumptions it involves. Readers looking for a compact summary of our findings are invited to jump to section 3.3 directly.

3.1 Evidence collected by the organisation

Our review of the evidence collected by AAC mainly distinguishes between two kinds of evidence: monitoring and evaluation evidence. These different aspects are often also called ‘process evaluation’ and ‘impact evaluation’ (BetterEvaluation, n.d.). The former aims to understand whether the programmes are properly implemented and how they could be improved (e.g., by understanding completion rates and satisfaction scores of a course), while the latter is focused on the observed changes caused by the programmes, also taking counterfactuals into account (e.g., improvements in participants’ capabilities or changes in their career outcomes that are a result of participation in a course). We consider as monitoring evidence everything that covers activities and outputs in our ToC (assumptions #1 to 9). The remaining part of the ToC (assumptions #10 to 21) is analysed with the help of evaluation evidence, as it is concerned with the outcomes and impact of AAC’s work.

We primarily use data that AAC has provided to us directly for this evaluation, as this should be the most up-to-date and accurate data available. We only referred to their yearly reviews (for 2020, 2021, and 2022) and impact page as well as Charity Entrepreneurship’s overview page on AAC where this seemed helpful or necessary.

In section 3.1.1, we first give an overview of the kinds of data that AAC is collecting, detailing their M&E approach and its strengths and weaknesses. In section 3.1.2, we then move on to describe the results and findings from this internal data. Across the two sections, we do not only describe AAC’s M&E efforts but also provide our perspective and make recommendations about improvements.

3.1.1 What type of evidence are they collecting?

3.1.1.1 Monitoring evidence

The approach

AAC collects different monitoring data for the different programmes they are running. AAC’s leadership reported to us that this data was scattered until recently, but they now have a comprehensive overview of monitoring data for their different programmes. We used this internal overview to understand what kind of monitoring data is collected for each of the programmes.

Below, we provide an overview of the metrics used for the different programmes described in section 1.2 (in alphabetical order). This list is probably not exhaustive but should cover the most important aspects. We exclude all impact-focused metrics (e.g. number of placements caused) here, since they are covered under evaluation evidence in the next section.

| Programme | Monitoring metrics |

|---|---|

| Career advice calls | 1:1 and group calls |

| Career advice resources | No clear monitoring found for this service |

| Earning to give | No clear monitoring found for this service |

| Fundraising work placement | Applicants Candidates placed Diversity of applicants and candidates Organisations participating Organisations satisfied with placements Dropouts (candidates and organisations) Time required for running programme |

| Inclusive hiring skills workshops | Organisations participating Paid tickets Repeat attendees Issues identified and addressed in events Usefulness and enjoyment of events |

| Job board | Roles listed Organisations included Page views (main and all other job board pages) Users (all job board pages) “Apply now” clicks “View job details” clicks Mailing list stats (e.g., subscribers, open rates) |

| Online course | Sign-ups Enrollments Completions and completion rate Certificates |

| Recruitment | Organisations supported Roles assisted with Candidates introduced to roles |

| Top candidate database | Candidates listed (incl. share from developing countries and with skills in key bottlenecks) Referrals from organisations |

In addition to these programme-specific metrics, AAC also collects monitoring data on their marketing efforts (assumption #7). This was reported to us by AAC’s leadership, but we did not see a comprehensive overview of this data and did not have the time to inquire further on this.

Our perspective and recommendations

Overall, AAC’s monitoring approach seems reasonable and it is positive to see that AAC has an overview of monitoring metrics for almost all of its programmes. These metrics can help to reduce our uncertainties on assumptions #2 to 9.

However, we see some areas that could be reviewed and potentially improved upon:

- We are unsure how the monitoring data is used to make decisions internally. We generally recommend that AAC make sure that all of this data is collected with a specific purpose in mind and that they focus on those metrics that are relevant for their decision making.

- Monitoring data is missing for those services that AAC provides to a broad audience via its website or general online presence, namely the generic career advice resources and its earning to give outreach. While we understand that it is hard to track the impact of activities whose effects are so scattered as for these generic services, we still think that there is some monitoring data that could be collected. For instance, just as for its job board, AAC could track the number of page views for its career advice resources. Even though such data might not provide a strong basis for evaluating the effectiveness of these programmes, they can be a first step towards understanding the relevance of different career advice pages (over time) and improving the services provided on that basis.

- For some of the programmes, AAC only collects ‘hard’ data such as the number of people and organisations affected, but neglects to collect ‘softer’ data that can yield more qualitative insights for improving the services. For instance, both the career advice calls and the online course do not seem to solicit feedback from participants on the services provided, understanding how valuable they are and how they could be improved. This might be a missed opportunity for AAC. However, we acknowledge the limitations of such data (e.g., positivity bias in responses) and understand the associated costs (e.g., effort for both AAC and its advisees). This should therefore be seen as a weaker suggestion than the other ones above.

3.1.1.2 Evaluation evidence

The approach

AAC adopts a meticulous approach to evaluating the impact of its programmes, mainly focusing on an innovative metric: the number of Importance- and Counterfactual-Adjusted Placements (ICAPs). This rigorous method underpins their commitment to steering more talent towards the animal advocacy movement, directly addressing assumption #15 in our ToC: the influx of more and/or better talent into animal advocacy organisations. Moreover, the evaluation of ICAPs extends to encompass people founding their own organisations or working in adjacent sectors like alternative proteins, thereby also informing assumption #20.

ICAPs are calculated via a three-step process:

- Identifying potential placements:

AAC's first step aims to detect new placements for people who previously participated in AAC’s programmes. This involves the quarterly monitoring of LinkedIn profiles and conducting annual surveys, as well as direct feedback from organisations. - Interviewing placements:

Once potential placements are identified, AAC tries to conduct interviews with each individual to assess the counterfactual impact of their services. This critical step determines the extent to which AAC's intervention contributed to the placement's success. - Assessing and adjusting placements:

The final step involves adjusting the placement score based on the counterfactuals identified in the interviews and making a subjective importance assessment based on the organisation's and the role's significance. These adjustments transform the placement figures into ICAPs. For each ICAP, AAC estimates an addition of $37,500 to the movement. This calculation is based on the assumption that each placement is at least 10% better than the next best candidate and will continue working in the movement for 7.5 years, with an average salary of $50,000 annually. In section 4, we will provide more details on the reasoning behind these calculations and describe our perspective on their validity.

Next to their ICAPs metric, AAC also monitors significant donations influenced by their efforts. This tracking is facilitated through communications with Giving What We Can, where pledgers are asked about contributing factors to their decisions, and AAC's annual surveys. For their most recent earning to give programme, AAC is collecting the number of giving pledges they caused. AAC has also tracked the funds raised and time saved for organisations participating in the Fundraising Work Placement programme. This involved surveying and interviewing participant organisations and assessing counterfactuals to determine the extent of the funds raised due to the programme. For the Fundraising Work Placement programme, AAC also collected further evaluation evidence, specifically how many participants changed their career plans after the programme.

Based on all of this data, twice a year, AAC conducts evaluations of each programme's performance to decide whether to stop, pivot, continue, or scale them up. This decision-making process is particularly challenging for newer programmes with fewer ICAPs. In such cases, AAC sets specific goals and failure points that programmes must meet to continue. Early-stage evaluations rely on programme data, feedback from organisations and candidates, and potential assessments relative to other AAC programmes. For more established programmes, the ICAPs generated are compared against the effort invested to estimate cost-effectiveness (see section 4). Some write ups of detailed evaluations of specific programmes are publicly available here and here.

Our perspective and recommendations

Overall, the description above documents an elaborate and rigorous evaluation approach. The use of ICAPs is an especially innovative and strong method to measure outcomes.

However, every approach will inevitably have its limitations. Below we list the most important limitations for AAC’s current methodology. We also explain if and how these limitations should be addressed, considering the costs associated with potential enhancements.

- Assumptions and omissions in ICAPs calculations:

- AAC’s approach for identifying placements possibly misses placements not represented on LinkedIn or through survey responses. This issue is especially relevant in developing countries. However, the current process employed by AAC seems reasonable and should cover the majority of placements influenced. Getting a completely exhaustive overview of all placements does not seem realistic and would be associated with excessive effort.

- AAC anticipates a time lag of 6-24 months between intervention and measurable results, meaning their most recent impact estimates (2023) could be significant understatements. This is an inherent limitation given the longer time periods over which AAC’s impact unfolds. Noting this limitation and considering it in evaluations in decisions seems sufficient.

- AAC experiences some drop-off in interview responses in step two and estimates that about 80% of their impact is traceable through these interviews. Once again, we think that this is a natural limitation for interviews and think that AAC’s current response rate is acceptable.

- All of the three bullet points above suggest that AAC’s ICAP estimates are conservative. AAC could add a factor in their calculations that accounts for such missing data. However, we appreciate that AAC only considers the impact of those placements that they know they have influenced and does not artificially inflate their ICAP estimates. We agree that it is better to err on the conservative side here.

- AAC’s assessment of counterfactuals and the importance of certain placements is subjective. They try to guard against this issue by averaging the scores given by two people. To ensure the accuracy and impartiality of these judgments, AAC has also sought feedback from external stakeholders and experts. We have also done some sanity-checks on their scores ourselves (see section 4). We think that AAC could improve its process here and reduce noise in its judgements, by implementing clearer guardrails on how to score different placements (e.g., via a scoring rubric or framework).

- AAC’s estimates for the monetary value of an ICAP are based on crucial assumptions that reasonable people could disagree about. We provide more details and our perspective on this in section 4.

- Volunteering roles/placements are not tracked and not included in the ICAP calculation. We are unsure why AAC decided to drop this measurement, but suspect this to be due to the low expected impact and high data collection effort involved. The fact that AAC is not tracking this implies that some positive impact of their work might not be tracked and makes their ICAP estimates more conservative. We are unsure whether AAC should track such volunteer placements as well but suspect that AAC has good reasons not to do so.

- AAC is not tracking attitude changes, career plan changes, or other behavioural changes (e.g., diet change). This seems reasonable, as AAC should focus on the most important metrics in order to avoid interview/survey fatigue.

- AAC does not seem to robustly evaluate the impact that its services have on hiring practices, specifically when it comes to the inclusive hiring skills workshops. AAC had initially planned to evaluate these workshops in more depth via follow-up surveys. However, they decided to suspend this service, as another organisation was founded that would focus specifically on this issue (Scarlet Spark). Given these developments, a thorough evaluation is not planned anymore. We think that this decision is reasonable, also given that this service was quite separate from AAC’s other programmes.

- Just as for the monitoring evidence (see section 3.1.1.1), AAC is missing a method to gather evaluation evidence for their career advice resources and earning to give programmes. While we understand that it is hard to track the impact of activities whose effects are so scattered as for these generic services, we think that AAC should attempt to capture the effects of this as well. In our interview, AAC’s leadership indicated that this issue is on their agenda.

- AAC does not measure how much faster individuals entered the movement due to their interventions, like other organisations such as 80,000 Hours do. This seems fine to us, as their impact on people’s careers is thoroughly assessed via their ICAPs metric.

3.1.2 What are the results from that monitoring and evaluation evidence?

As we now understand how AAC collects its internal data, we can describe what the results from that data collection look like in practice. As in section 3.1.1, we start with monitoring data (section 3.1.2.1) and then move on to evaluation data (section 3.1.2.2).

3.1.2.1 Monitoring evidence

The hard data

It is hard to give an overview of monitoring data that allows for cross-programme comparisons. As described in section 3.1.1.1, AAC collects different monitoring evidence for the different programmes it is running. In addition, the programmes have been run for different time frames and with different levels of effort invested. We therefore only record the numbers in the table below for readers to get a rough sense for different metrics across the different programmes for certain time frames. The numbers should be taken with caution, as we are unsure whether we read AAC’s data correctly. They should be directionally correct though. The programmes for career advice resources, earning to give, and recruitment are not included, based on the analysis in section 3.1.1.1.

| Programme | Time frame for recorded data | Orgs | People | Other

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career advice calls | 2020- 2023 YTD | - | 69 group coaching calls, 239 1:1 calls | - |

| Fundraising work placement | 2022 | 9 participating, 8 satisfied with placement, 1 dropping out | 150 applicants, 9 placed, 1 dropping out | - |

| Inclusive hiring skills workshops | 2023 | Unsure | Unsure | 65 paid tickets in total |

| Job board | 2023 YTD | 136 included | 104,879 page views, 23,400 users, 27,328 “View job details” clicks, 13,567 “Apply now” clicks | 776 roles listed |

| Online course | 2020- 2023 YTD | - | 2,906 sign-ups, 2,360 enrollments, 613 completions, 480 certificates | - |

| Top candidate database | Dec 2022- Nov 2023 | 31 participating | 170 candidates listed | - |

As described in section 3.1.1.1, we did not have access to a comprehensive overview of AAC’s monitoring data on marketing activities and did not have the time to inquire further on this.

Further context and our perspective

In addition to this rough overview, we can provide some further insights and our perspective on the different programmes:

- Career advice calls have been a steady component of AAC’s work since the very beginning. The number of calls fluctuates over the different years. We expect this to be the result of this service being very time-intensive and AAC experimenting with 1:1 versus group calls. We know that the demand for these calls is high, but AAC needs to prioritise and can only allocate certain amounts of time to this service.

- The initial fundraising work placement programme seems to have been well-received. The list of partner organisations for this initial programme seems impressive, including Animal Ethics, Sentient Media, Veganuary, Animal Advocacy Africa, and many more. The number and quality of applicants was also strong. In addition, AAC has conducted an assessment of the diversity of applicants and candidates for this programme. We did not check this in detail due to the limited amount of time available for this report.

- The data for inclusive hiring skills workshops is very scarce and unclear. This makes sense in light of AAC’s decision to drop this service, as described in section 3.1.1.2. We therefore did not investigate this further.

- The job board is steadily growing, both in terms of the number of roles listed and organisations included, as well as the number of people visiting and using it. This is a positive indication that the programme is running well.

- The online course has also been a steady component of AAC’s work since the beginning. The number of people who sign up, enrol, and complete the course has grown steadily over the years. We observe a slight drop in completion rates over time, but nothing that seems worrisome.

- The top candidate database has been steadily growing for the first few months of operation. It seems too early to draw any conclusions here though.

These findings positively update us on assumptions #3 (career advice calls), 4 (online course), 5 (fundraising work placement), and 6 (job board). A slight positive update on assumption #8 (top candidate database) could also be warranted. The data does not help us to reduce our uncertainty around assumption #2 (career advice resources), 7 (marketing and outreach activities), and 9 (inclusive hiring skills workshops) though.

3.1.2.2 Evaluation evidence

The hard data

When it comes to evaluation evidence, the crucial metric AAC uses are ICAPs. As described in section 3.1.1.2, ICAPs are calculated for all programmes except for career advice resources, earning to give, and the inclusive hiring skills workshops. Since AAC has a comprehensive overview of ICAPs generated by each programme, we can directly replicate their evidence in the table below. It represents all ICAPs generated by AAC in the years 2019 to 2023 YTD. The last column sets the number of ICAPs generated in relation to the amount of resources invested into the programme. This allows us to draw conclusions on the relative effectiveness of the different programmes.

| Programme | Base placements | ICAPs | USD cost per ICAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Career advice calls | 22.1 | 14.6 | 3,056 |

| Fundraising work placement | 5.0 | 3.2 | 39,028 |

| Job board | 16.8 | 10.0 | 1,827 |

| Online course | 31.9 | 8.4 | 6,335 |

| Recruitment | 3.5 | 1.4 | 30,353 |

| Top candidate database | 2.0 | 0.5 | 41,289 |

| Other | 4.8 | 1.8 | - |

| Total | 85.0 | 39.9 | 17,644 |

Further context and our perspective

These numbers are highly relevant, but of course need to be put in context. Below, we provide some further insights and our perspective on the different programmes:

- Due to their central position in AAC’s evaluation efforts, it is important to check the validity of the ICAP estimates above. In order to do so, we perform some sanity checks and sensitivity analyses in section 4. For now, we will take these values as given.

- The career advice course, job board, and online course are the three most cost-effective programmes for AAC. These three programmes are well-established and AAC should continue to run them in the foreseeable future.

- Career advice calls seem cost-effective, but require large time investments. AAC is thus trying out different ways to make this even more efficient.

- The online course is also well established and cost-effective, but is much more scalable.

- The job board seems to be the most cost-effective programme when it comes to creating ICAPs. In addition, since it is fairly difficult to collect feedback from job board users (as for the other website content, as highlighted earlier), the number of ICAPs caused by AAC might be significantly higher and the cost per ICAP even lower.

- The cost per ICAP is relatively high for the fundraising work placement, mostly due to the high effort involved and the large funding amounts needed. However, a large share of participants has landed a permanent role after the programme. Next to ICAPs, AAC has measured the amount raised by participants for the partner orgs, estimating roughly USD 270,000 added and raised counterfactually. Overall, this seems like a high-quality but also high-effort service. AAC seems somewhat positive about the programme and is aiming to run this again or facilitate a similar programme run by another organisation. The focus of this next iteration would be on legal and policy roles instead of fundraising. We are unsure whether this should be a priority area for AAC, as its other services seem more effective and the costs seem too high (see section 4.1).

- As described in section 1.2, AAC has suspended the recruitment programme. The low number of ICAPs generated was a main reason for this. The top candidate database was set up to succeed this service. This new programme is still in its early stages and ICAP numbers should not be relied on heavily at this point yet. AAC seems to be happy with the initial KPIs they are seeing and will need to monitor how the ICAP metric develops over time.

- We did not have the time to analyse in detail how AAC’s services influence people’s donations.

- Due to a lack of data, we could not understand the outcomes and impact of AAC’s career advice resources, earning to give programme, and the inclusive hiring skills workshops.

Overall, the evaluation evidence demonstrates that AAC has counterfactually caused people to change career paths and assume roles within the movement. This positively updates us on assumptions #10 (founding of new organisations), 11 (strong career paths in related areas), 13 (strong career paths and capabilities for work in the movement), 14 (increased awareness of opportunities), and 15 (influx of talent to the movement). The evidence on assumption #12 (increased donations and funding) is less strong, given that we have seen evidence of increased funding as a result of the fundraising programme but have not had the time to analyse the effect of AAC’s services on people’s donations and the earning to give programme is still in its early stages. We could also not update our uncertainty around assumption #16 (improved hiring practices at organisations) due to a lack of evaluation data for the workshops. Assumptions #17 to 21 were not investigated in detail due to our low uncertainty around them and the absence of relevant data.

3.2 External evidence not collected by organisation

Apart from the evidence that AAC has collected internally, we also need to look at external pieces of evidence that can inform our opinion about the kinds of programmes AAC is running and how likely their ToC is to hold. We specifically took the following steps in order to broaden our perspective on AAC’s work and reduce key uncertainties.

- We did a quick, time-capped literature review on assumption #13 in our ToC, as it is one of the most crucial breaking points in our ToC and we thought we could reduce our uncertainty on this assumption with the help of external evidence

- We reviewed evaluations of EA career interventions that are similar to AAC’s work, looking for findings that might be cross-applicable. Most importantly but not exclusively, we looked at the findings from 80,000 Hours’ annual reviews since 2019.

- We consulted Animal Charity Evaluators’ review of AAC in 2022, especially looking for crucial aspects that we had not considered and checking how their perspective lines up with ours.

3.2.1 Academic studies on the effect of career services on career plans and capabilities

Due to the limited time available for this research, we decided to focus our efforts in looking for external academic evidence on the plausibility of AAC’s ToC on assumption #13: “Consumers of AAC’s services enhance their career plans and capabilities for work in direct animal advocacy”. Among the three most crucial and uncertain assumptions in the ToC (#1, 13, and 15), this was the assumption we thought could clearly benefit the most from external research. Assumption #1 was already covered by other pieces of evidence (as described in our needs assessment in section 1.1) and #15 seemed highly specific to AAC’s work and a review of external literature did not seem likely to yield highly relevant insights.

As a result, we focused our attention on the question how likely different AAC services are to influence career plans and capabilities of advisees. In line with the ToC, we focused our attention on those services that aimed to influence these outcomes, namely AAC’s career advice (both in generic as well as personal form), online course, and fundraising placement programme. We investigated each kind of service in a quick literature review, using standard tools like Google Scholar or Elicit.

Career advice

In order to evaluate the effects of career advice, we grouped the generic online-content version and the more personal and direct version of AAC’s services together, since some of the best studies we found included different kinds of career advice interventions.

For instance, one random-effects meta-analytical study from 2023 sought to determine the “impacts of career guidance interventions on school students' career-related skills, knowledge and beliefs” (Nargiza et al., 2023), evaluating empirical studies carried out over the previous 10 years, including nine studies involving a total of 1,433 participants. The analysis resulted in a weighted mean effect size of 0.42 (95% confidence interval = 0.19, 0.65; z = 3.61, p < 0.01), which they interpreted as a moderate-to-high effect size, noting a significant difference between the treatment and control conditions at post-treatment. They found that post-test career-related outcomes in students which received career guidance were significantly higher than for students who did not receive career guidance. This suggests that career guidance interventions may provide some modest developmental progression in school-age children and adolescents, “particularly through improving learners' career decidedness and attitudes such as future time perspective” (Nargiza et al., 2023). Notably, the types of interventions varied between studies, but included short to medium term interventions such as a training programme to improve emotional intelligence, a programme aimed to promote learners’ future time perspective and to learn about the current world of work and vocational planning. (Nargiza et al., 2023)

Similarly, another meta analysis of different career choice interventions found that the targets of such interventions scored roughly one third of a standard deviation higher on various outcome measures like career maturity, career decidedness, career decision-making self-efficacy, perceived environmental support, and perceived career barriers (Whiston et al., 2017).

A review by Mackay et al. (2015) found that no single intervention or group of interventions appeared most effective in improving career management skills. However, they identified the five components below which underpinned the interventions that substantially increased effectiveness and can be considered by AAC in their intervention design:

- The use of narrative/writing

- The importance of providing a ‘safe’ environment

- The quality of the adviser-client relationship

- The need for flexibility in approach; the provision of specialist information and support

- Clarity on the purpose and aims of action planning

Specifically related to direct, personal career advice, we found some further evidence. Due to a lack of abundant meta analyses or systematic reviews, we decided to include one well-designed non-meta study of career counselling. This study found decreases in career indecision and increases in life satisfaction for recipients of career counselling. “The majority of clients implemented their career choice within a period of one year; some partially implemented it; others changed their career choice, rather successfully; and few people did not demonstrate advancement in either their choice or its implementation during this period of time” (Perdrix, 2012). We also decided to include a meta analysis of the effects of mentoring here, since mentoring and career advice calls share significant similarities. This meta analysis on the effects of mentoring finds benefits on career outcomes at small effect sizes (Allen et al., 2004).

Overall, we find strong evidence that career advice can boost capabilities, career outcomes and plans.

Online Courses

Allen et al. (2006) conducted a meta analysis to compare the test performance of students that engaged in distance versus traditional learning. They found that “distance education course students slightly outperformed traditional students on exams and course grades”. The U.S. Department of Education (2010) reported similar findings in their meta analysis, showing modestly stronger performance of students in online learning versus face-to-face settings. Mathieson (2010) systematically reviewed the results for statistics courses specifically and found student performance to be similar between online and face-to-face learning. Gao et al. (2021) found that exam performance for medical courses in China was higher in participants of massive open online courses versus traditional courses. In sum, all of the relevant meta analyses and systematic reviews we identified in our quick review of the evidence point at the ability of online courses to positively influence student’s capabilities.

When it comes to the effect of online courses on career plans, we could not identify any strong studies in the short time available. The best evidence for this clearly seems to be AAC’s (2023) own evaluation of the effects of their career advice and online course on career-related outcome measures. This was already summarised in section 3.1.2.2 and we can neither positively or negatively update our view based on external evidence here.

Overall, we find good evidence that online courses are an effective tool for learning and can improve participants’ capabilities. The effect on career plans is not clear.

Fundraising placement programme

Inceoglu et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of quantitative studies that either offered a control group or a longitudinal design, seeking to evaluate the effectiveness of placements for career outcomes. They screened 2394 studies and retained 40 for an in-depth review. They identified that “Placement participation elicits an overall positive (but small) effect on career outcomes”. Most notably, graduates who completed placements found employment more quickly, and students’ perception of their own self-efficacy, knowledge, skills, and attitudes were improved.

A report by the UK Department of Education (2021) corroborates the general finding that work placements have a small, positive association with career outcomes. Looking at employability programmes and work placements in UK Higher Education, they find that “research looking at students’ own assessments tended to find almost ubiquitous evidence of perceived skill development”. Indeed, they conclude that even when statistical techniques are employed to account for selection effects from ability or motivation, “a positive, albeit possibly smaller, wage return to work placements is seen [...], as well as a positive impact on employment outcomes such as the likelihood of being invited to interview”. However they also note several concerns with the methodology and sparsity of evidence available in this field. In particular, they identify that “even in the literature on opportunities, costs and benefits for students or graduates, the research evidence tended to be piecemeal rather than comprehensive.” Further, they note that skill development does not always translate into improved labour outcomes, and posit several explanations for this, such as that not all work placements develop skills equally and that work placements are associated with improved career outcomes as they serve as signals to employers rather than necessarily increasing skills.

Another systematic review, focused on international internships and skill development, found that in 9 out of 49 studies reviewed, career decision-management was identified as a skill gained through participation in international internships by students in higher education (Di Pietro, 2022).