We’re excited to share a new addition to our site: a section dedicated to climate change in our new-look cause areas page!

Needless to say, many people worldwide are passionate about tackling climate change as a path to improving the world. We believe there’s a need for accessible, scale-sensitive advice that helps people direct their efforts in this space. We want to help meet this need, alongside our continued work in several other cause areas.

To this end, we’ve been diving into climate change over the course of this year, and we’re really excited to finally share what we’ve been working on - starting with three new articles:

- Climate change: An impact-focused introduction

- What are the biggest priorities in climate change?

- What are the best jobs to fight climate change?

Below, we’ll give a quick overview of each of the articles.

Climate change: An impact-focused introduction

This article aims to provide an accessible and relatively brief introduction to climate change from a scale-sensitive perspective. Similar to our overviews of other cause areas, it assesses climate change using the ITN framework, addressing some of the key considerations for prioritizing climate change relative to other cause areas.

Here’s a short excerpt from our section on the scale of harm caused by climate change:

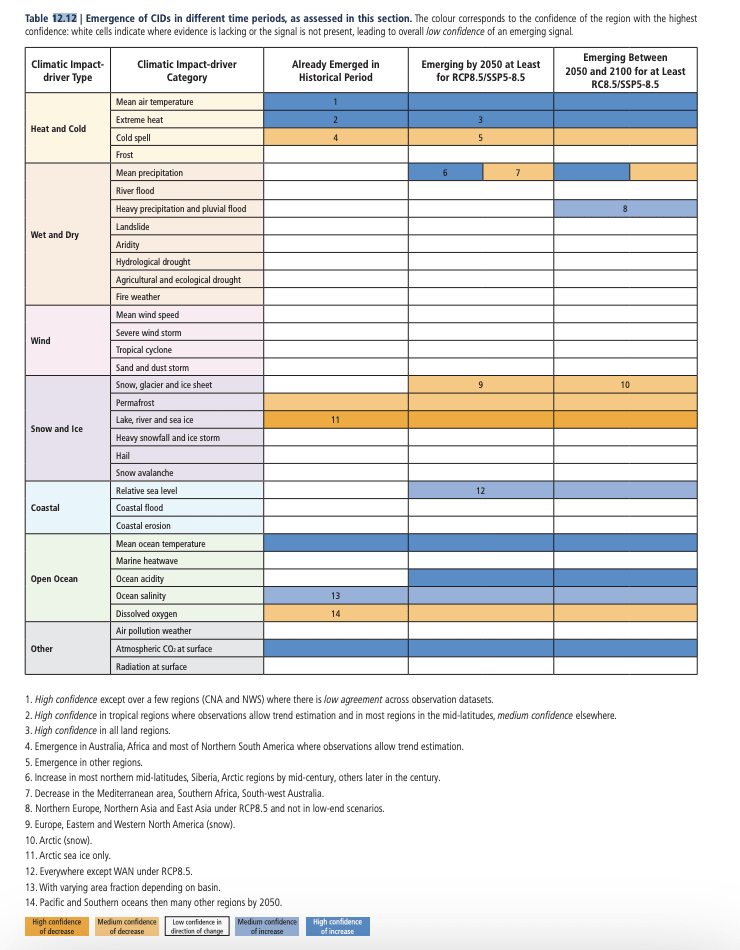

Climate change has and will continue to increase the frequency and severity of many risks, including heat stress, forced migration, poverty, water stress and droughts, natural disasters, food insecurity, and the spread of many diseases.

However, the extent to which these risks increase will depend on how well we’re able to mitigate the amount of climate change that occurs. An often-cited target is to keep warming to below 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, something most of the world’s countries agreed to target in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

At 1.5°C of warming, we would avoid some of the worst effects of climate change, though the harm would still be huge. For instance, nearly 14% of the world’s population could experience severe heatwaves at least every five years, and over 132 million people could be exposed to severe droughts. Environmental damage and biodiversity loss will also occur, including damage to coral reefs, the vast majority of which may not even survive 1.5°C of warming.

However, it now looks likely that we’ll surpass 1.5°C relatively soon, despite these international targets. This makes higher levels of warming, and therefore increased harm, even more likely by the end of this century.

At 2°C of warming, for example, between 800 million and 3 billion people may suffer from chronic water scarcity, and nearly 200 million may experience severe droughts. Three times the number of people will experience severe heatwaves at least every 5 years at 2°C compared to 1.5°C – an additional 1.7 billion people. This will take a significant toll on human life; recent research estimates that at slightly over 2°C of warming, nearly 600,000 additional people could lose their lives every year by 2050 due to heat stress compared to current levels.

At higher levels, the picture looks even more extreme. At 3°C, we could see a five-times increase in extreme events relative to current levels by 2100 (as opposed to a four-fold increase at 1.5°C of warming), and at 4°C, up to four billion people will experience chronic water scarcity. This is one billion people more than would experience chronic water shortages at 2°C of warming. Other effects of climate change would also considerably ramp up as warming increases.

Fortunately, thanks to the work of climate activists who have increased the amount of global attention focused on climate change, we’ll likely avert some of these most severe projections. The IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report predicts that, even if we fail to undertake significant further action, it’s very unlikely that we’ll reach 3°C or more of warming.

But this shouldn’t paint too rosy a picture. As we’ve seen, the effects of climate change below 3°C will still be destructive and widespread.

On top of this, there’s still a lot of uncertainty over the precise effects of climate change, even at lower levels of warming. For instance, there remains a chance of catastrophic climate effects caused by “tipping points” in which abrupt changes to the climate may occur after some threshold is exceeded. An example is the thawing of the Arctic permafrost, which would release vast amounts of methane. Additionally, the possibility of dangerous feedback loops – where contributors to climate change mutually reinforce each other – could stand to cause sudden, severe, and potentially irreversible changes to the climate. These scenarios seem to be unlikely, but their potential severity makes them worth taking seriously as a catastrophic risk.

And regardless of the amount of warming we experience, the harms of climate change are set to disproportionately affect people and regions that are already worse off, exacerbating existing global inequalities.

On top of this, some are also concerned that the effects of climate change may indirectly exacerbate other large-scale risks, too – such as increasing the chance of international conflict via pressures induced by increased migration and resource scarcity. These considerations increase the importance of climate change beyond its direct effects.

So, as many people around the world have already recognized, climate change is an incredibly important global problem from a variety of considerations.

What are the biggest priorities in climate change?

This article is the most substantial piece of our new content on climate change. It provides a rundown of some of the highest-priority problems in both the mitigation and adaptation spaces. It aims to help clarify where people might be able to make the most meaningful difference within specific challenges related to climate change.

Here are a couple of excerpts from our sections on animal agriculture and heat stress to give you a flavor of the article:

Animal agriculture

Importance: ≈7 billion tonnes CO2e per year

Tractability: Low

Neglectedness: Low

Agriculture is responsible for a large proportion of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. And within agriculture more broadly, animal agriculture specifically contributes disproportionate amounts of greenhouse gasses. Estimates of just how much it contributes vary, but the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization claims that livestock are responsible for 14.5% of total global greenhouse gas emissions (from all sources).

In significant part, this is because livestock produces methane, a greenhouse gas that carries over 25x more potential to warm the planet than equivalent amounts of carbon dioxide. On top of this, growing crops for animal feed also contributes to animal agriculture’s carbon footprint – both in the direct processes involved in producing feed, but also in the deforestation required to create arable land, which releases large amounts of sequestered CO2.

[Article continues...]

In summary: Animal agriculture is a significant contributor to climate change, and unlike some other contributors, it is not showing much sign of slowing down. This area may be especially promising for those who have an outsized advantage in tackling seemingly stubborn problems, such as enabling big policy wins or accelerating the adoption of alternative proteins.

Heat stress

Importance: Up to 580,000 fatalities per year by 2050 (at slightly over 2°C of warming)

Tractability: Low

Neglectedness: Moderate

Temperature has been shown to have a surprisingly significant effect on mortality rates. Even mild deviations from optimal temperatures have been shown to increase mortality risk, primarily through increasing the prevalence of many different causes of death, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as strokes.

This is a cause for concern since global warming stands to increase ambient temperatures around the world. Putting some numbers to this, recent research suggests that we could see as many as 580,000 additional deaths per year by 2050 due to increased temperatures, assuming a warming of slightly over 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

[Article continues...]

In summary: Heat stress is (perhaps surprisingly) plausibly the largest anticipated harmful effect of climate change in terms of mortality. Though it’s a difficult problem to make progress on, the scale of harm it causes means it could be a highly impactful area to work on, particularly for those who can increase the resources available to adapt to heat stress or develop and improve scalable solutions.

What are the best jobs to fight climate change? A guide to careers that will help the most

This article points towards a few careers that could help make a meaningful difference within the top priorities in climate change. We also explain why a couple of career options people often gravitate towards may not be quite as promising.

It’s far from an exhaustive list, but we think this article is a good alternative to the most popular articles on this topic you can find online. For instance, one of the top search results for “Top Climate Change Jobs” lists Urban Grower and Pedestrian and Bike Lane Construction Consultant among its top recommendations. While we don’t want to throw shade toward these professions, we believe there are more promising options people might want to pursue instead.

Here’s an excerpt from our discussion of jobs in climate science:

Job description: Climate scientists work in various scientific disciplines that study the physical, chemical, and biological processes that affect the Earth’s climate, as well as understand human influences on climate change and how to mitigate them. They can work in academia, government, as well as climate tech companies, and even advocacy.

Entering the field: Though the paths of climate scientists are varied, typical undergraduate degrees in a related subject such as physics, environmental science, meteorology, mathematics, computer/data science, and other degrees in the natural sciences are likely to be suitable. However, climate science roles in which you conduct your own research, and therefore offer more leverage, will typically require a PhD.

Why we’d recommend climate science: Climate science is a versatile field that can facilitate work on many issues related to climate change, including some topics that are very important but neglected relative to others. Such topics may include climate change “tipping points”, or effects of climate change specifically in tropical regions and low- and middle-income countries. Climate scientists who develop sufficient credibility may also be able to use their credentials in impactful ways in parallel to their scientific work or at a later stage in their career, such as performing advocacy work, directing climate change policy, communicating to the public, or working as a climate-focused grantmaker.

Other considerations: Climate scientists will generally make the most positive difference by researching areas that are the most important, tractable, and neglected within climate change. However, incentives within different organizations might often work against this. For instance, in academia, the research that is most likely to get funding or be published in top journals may not always be aligned with research that is the highest priority.

As a result, climate science is a promising path, especially if you can find a role that lets you focus on the most important and neglected questions within climate change. It’s also important that you’re a particularly good fit for research roles, which typically require significant enthusiasm for the subject area given the competitiveness of the field and the often independent nature of the work.

Final notes

As always, we’d love to hear your feedback. Additionally, if you’ve read the above articles and found them helpful, we think you might be a good candidate for our free 1-1 advising service. If you’re interested, please apply on our site - or send the page to anyone you think might benefit from an advising call!

Thanks a lot for the response! I was the main researcher for these articles - here are a few thoughts from me and the team:

It’s a little tricky for us to evaluate the consensus on these issues ourselves as we don’t have the capacity or expertise to review all the relevant papers and assess their relative influence. (We’d welcome anyone sharing their views on this, especially if they have expertise in the field!)

Because of this, we typically defer to respected authorities – especially the IPCC – which is likely a decent proxy for expert consensus. While any one institution will inevitably have its shortcomings, the IPCC's comprehensiveness in reviewing the literature is impressive, and they do a fairly good job of representing their uncertainty based on the literature in their reports.

That being said, there seems to be a lot of uncertainty about expected adaptation efforts, perhaps more so than there is uncertainty about the direct effects of climate change, and the extent to which the IPCC provides estimates accounting for adaptation depends on the problem. In short – we don’t really know, (though we’re open to being corrected on this).

Because of this, when trying to estimate the value of working on adaptation, given high uncertainty about how much of it will take place without our intervention, as well as a reportedly widening adaptation finance gap, it’s still worth thinking about the expected impacts assuming minimal or current-trajectory adaptation. Though, naturally, the more we learn about the impact of expected adaptation efforts, the better.

Here’s a few more specific points on deaths from non-optimal temperatures and natural disasters:

On temperature and mortality:

When discussing the promisingness of an adaptation response to heat stress, we think what matters is the absolute numbers of heat-stress-related deaths, which we can be quite confident will significantly increase, and not whether on net climate will cause or prevent more deaths (taking into account other types of deaths prevented). We included the estimate that increases in fatalities will outweigh reduction in deaths because it provides interesting and relevant context, not because it directly bears on how promising this area of adaptation is.

It’s also worth noting that even Zhao (2021) claims that ‘in the long run, climate change is expected to increase the [temperature-related] mortality burden’, even if it reduces mortality in the short term. They don’t give any concrete projections, so it’s unclear the extent to which the numbers we’ve given align with this claim – but the direction is the same. Nonetheless, this does complicate the discussion around temperature-related mortality, so thanks for bringing it to our attention!

On natural disasters:

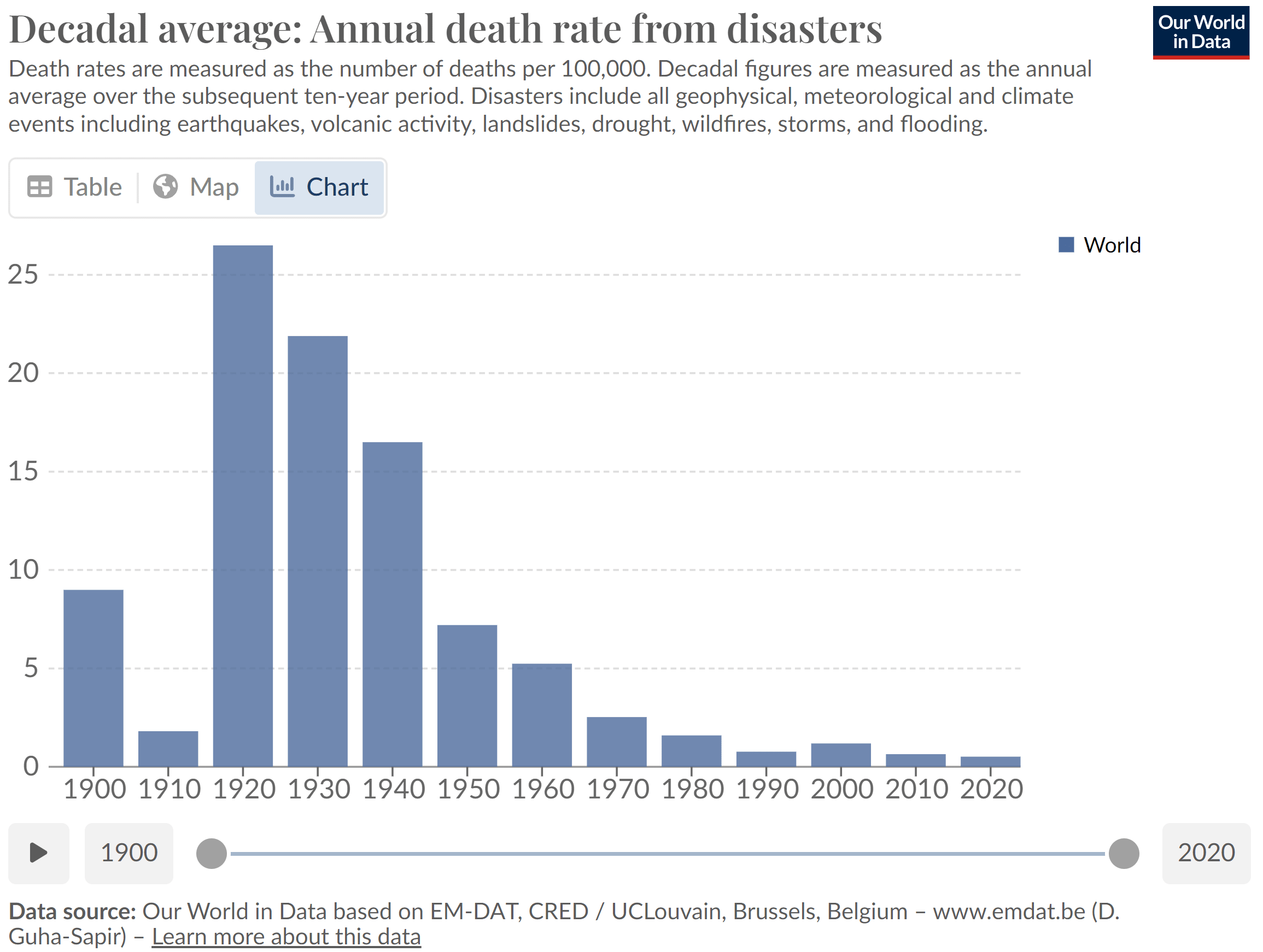

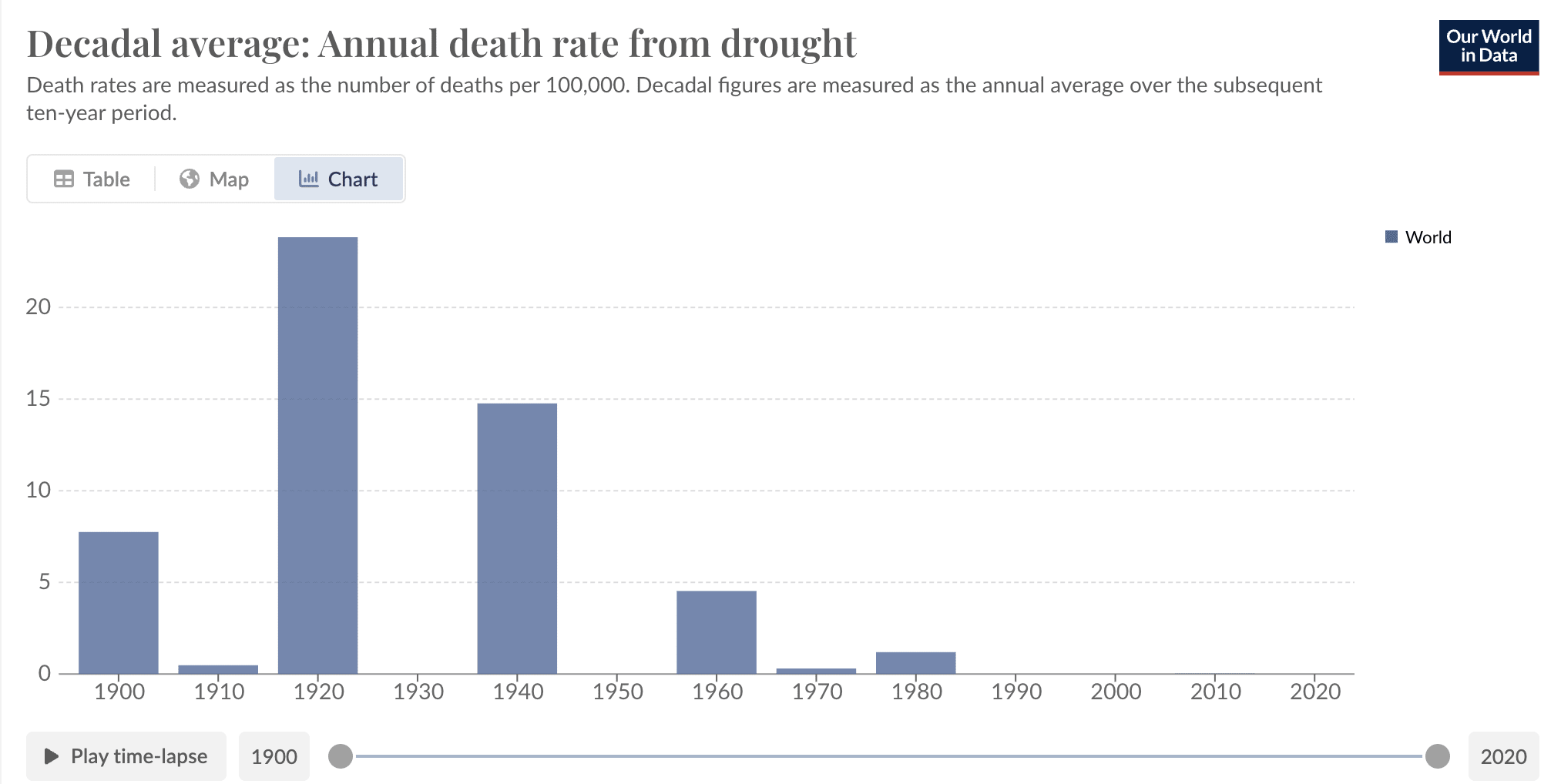

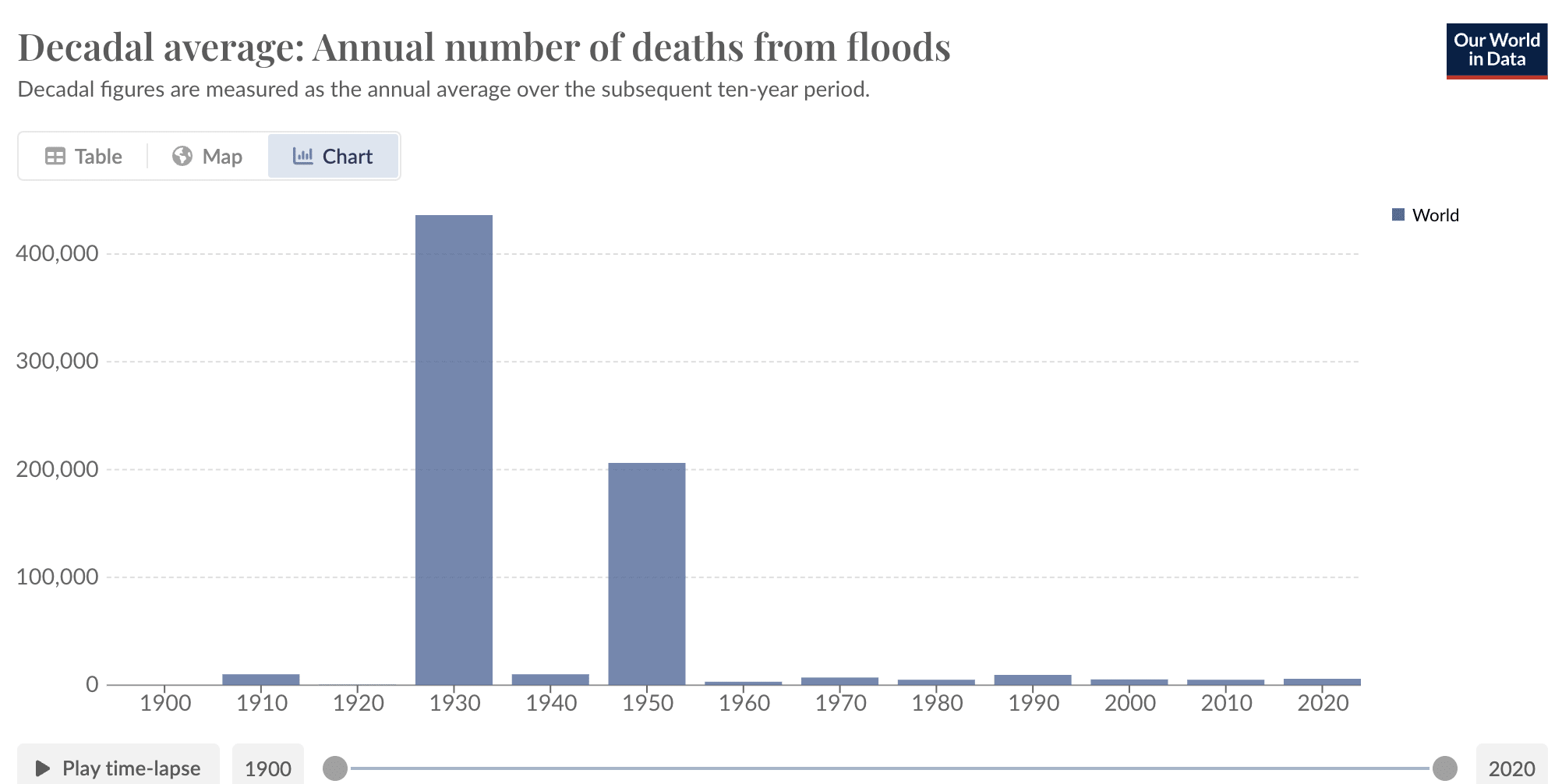

First, although fatalities from natural disasters have decreased, most of this reduction has been in high-income countries (if you look at the OWID page and filter by low-income countries, the downward trend is much less clear).

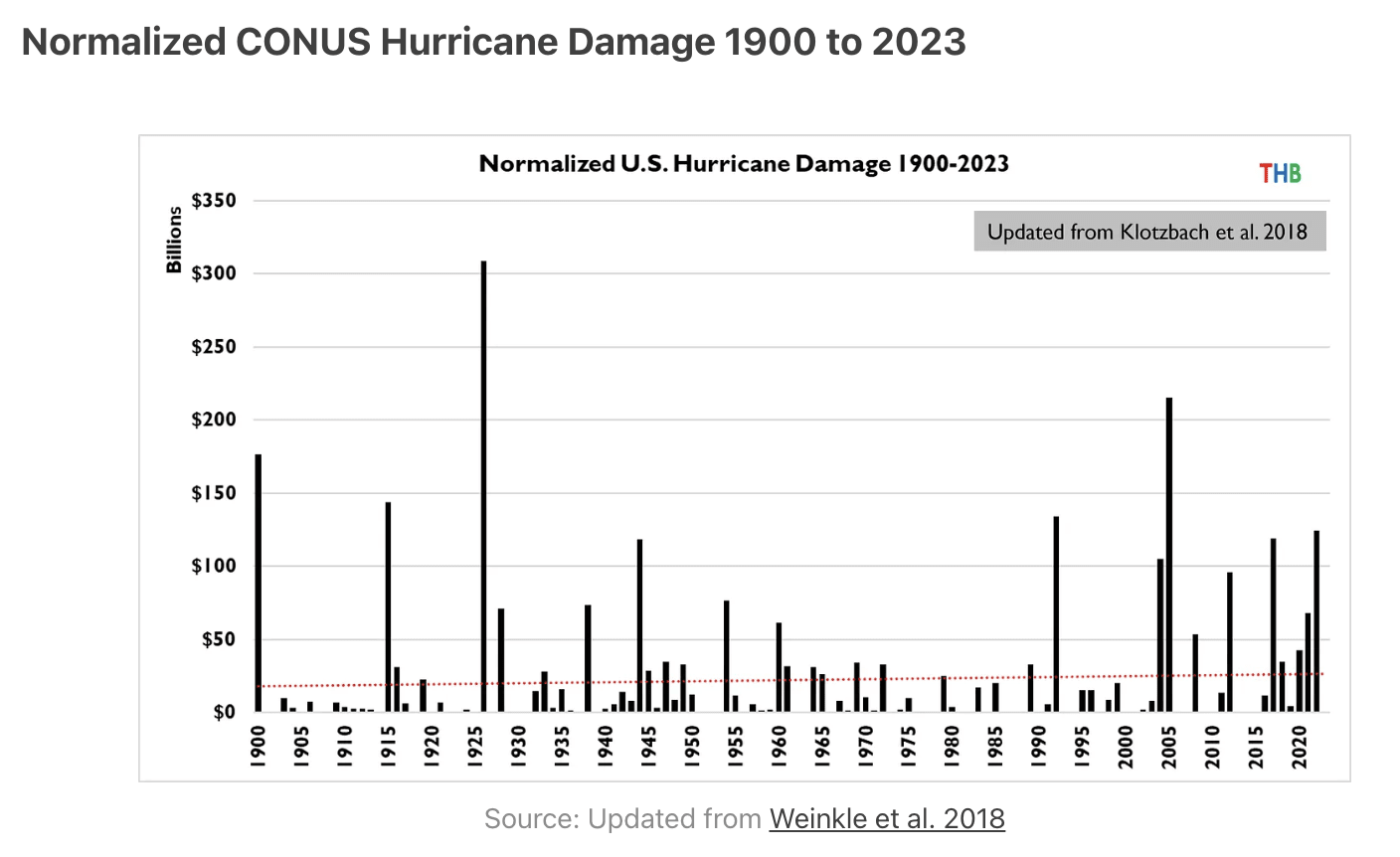

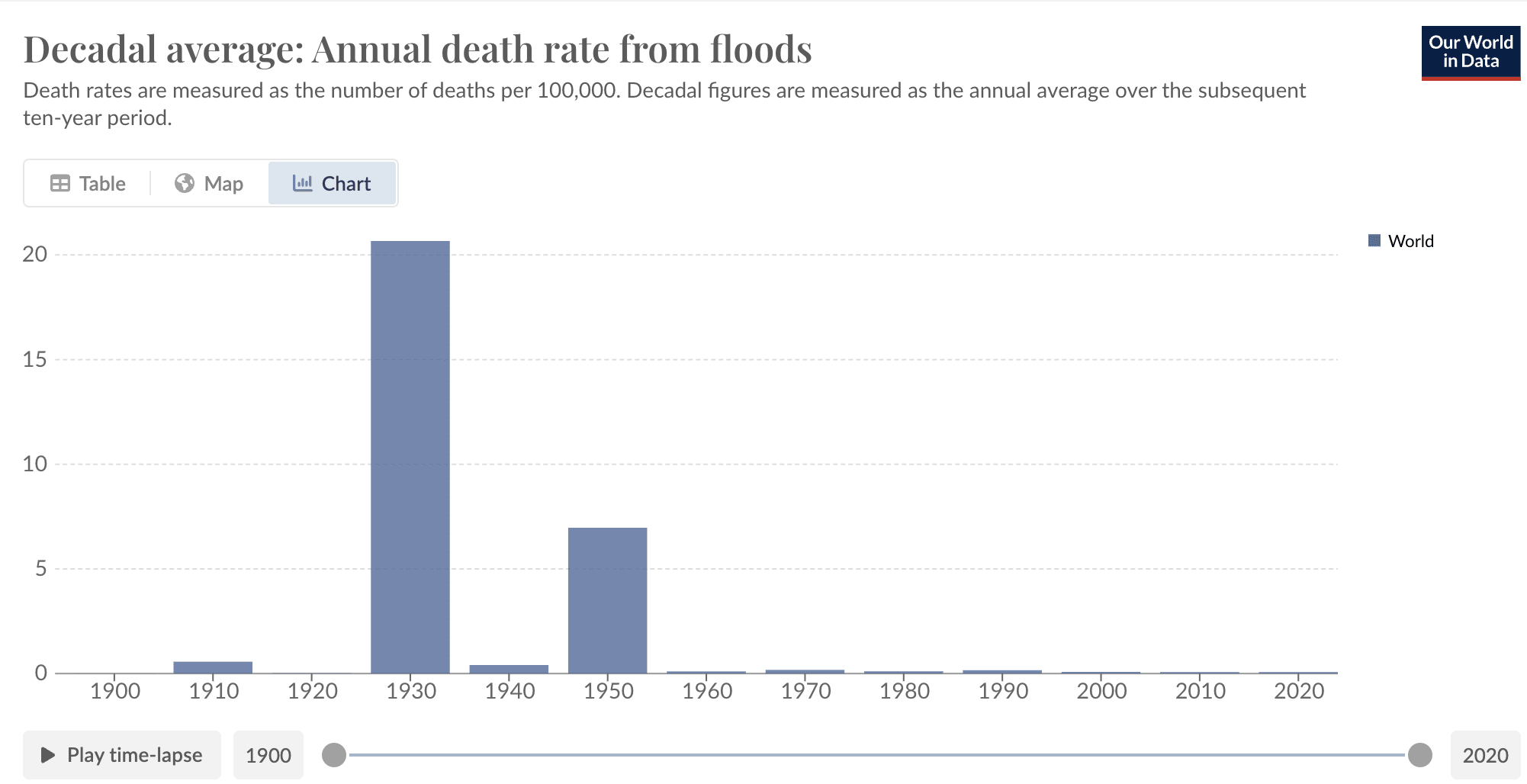

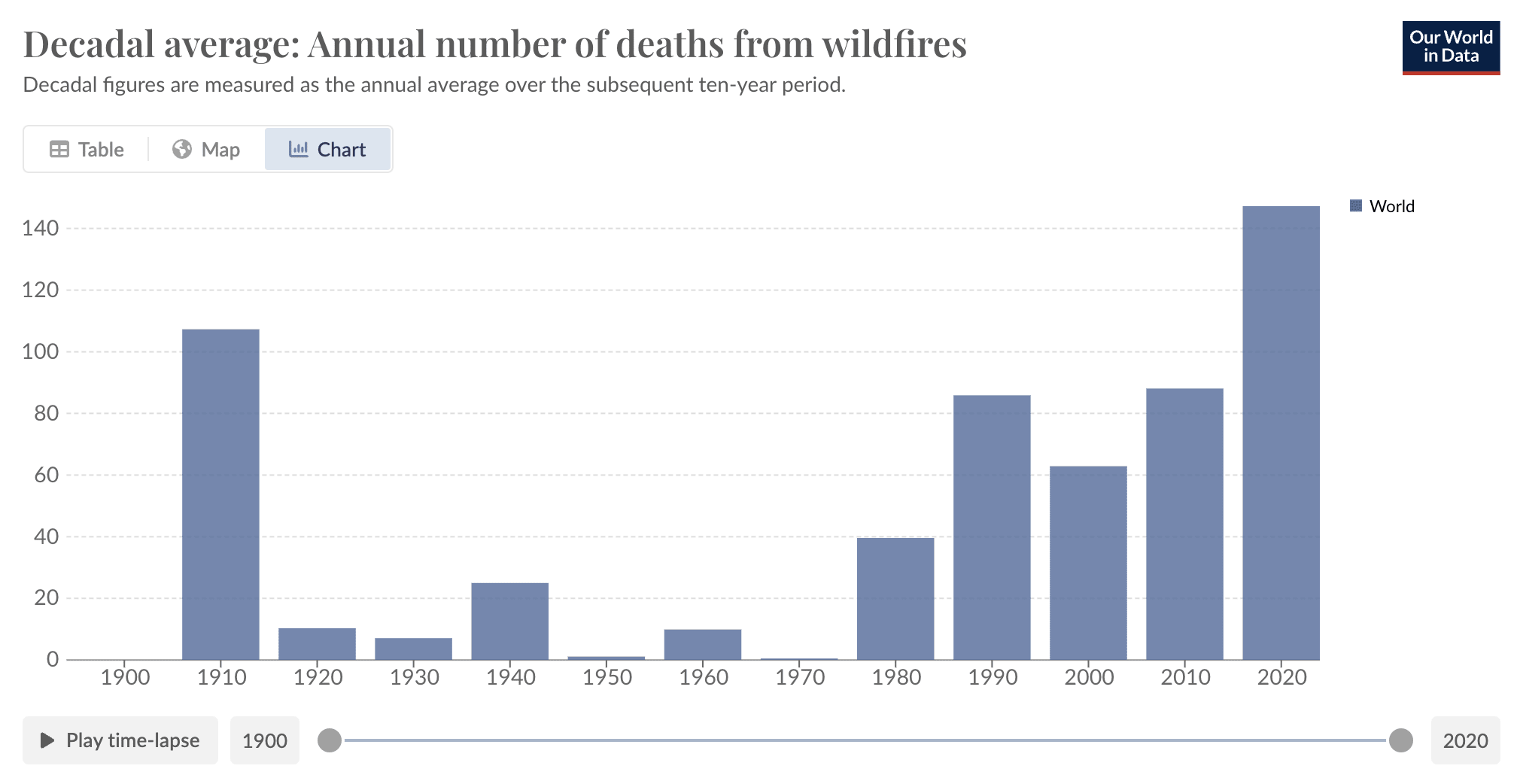

Additionally, looking at the decadal average of all natural disasters can hide how sparse the data points driving this impression are. If we look at the year-by-year view of natural disaster deaths, just a handful of terrible events are responsible for the vast majority of deaths throughout the 20th century, which means we’re wary about inferring long-term trends from the decadal view – especially for events that fit a power-law distribution.

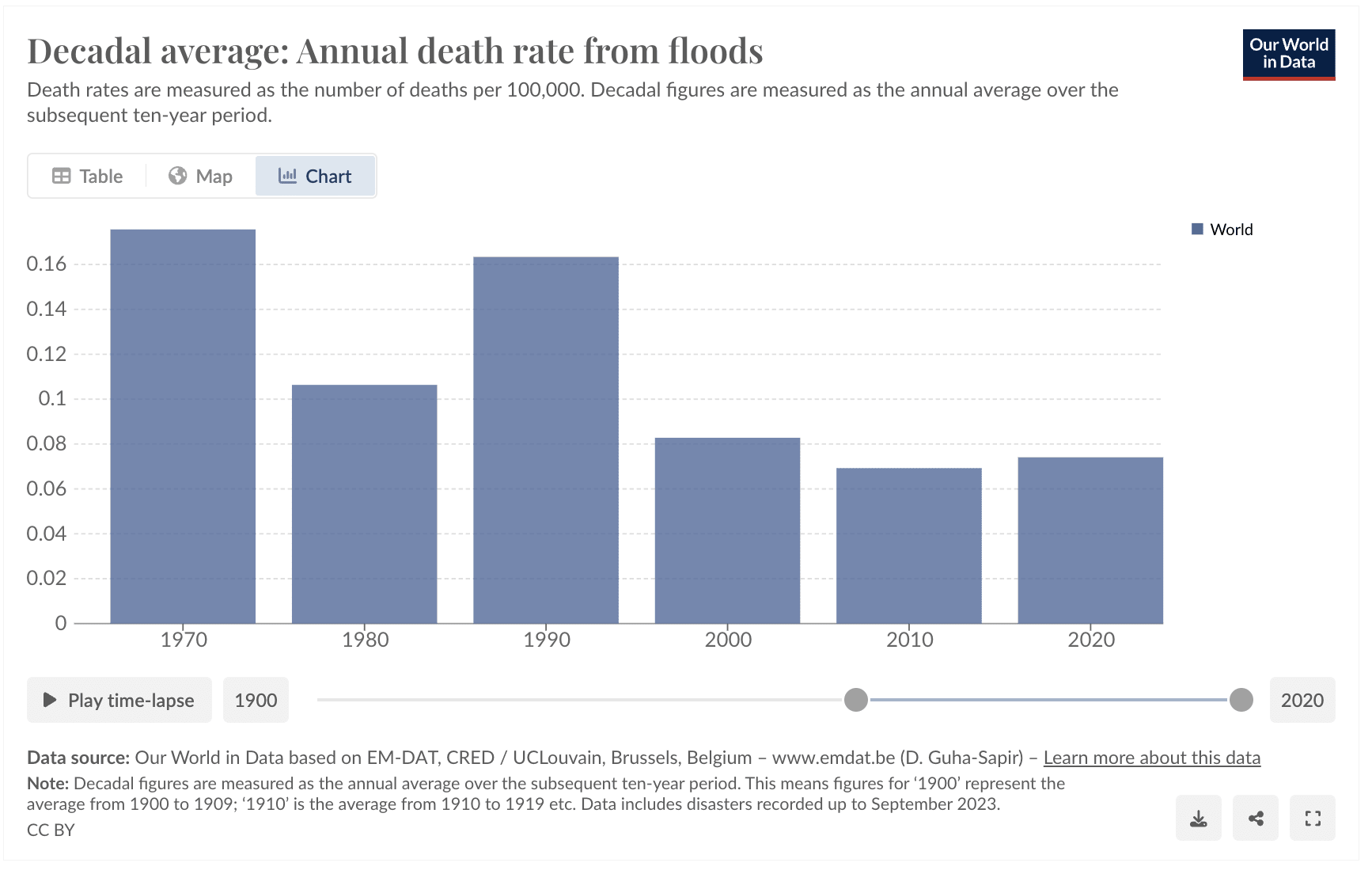

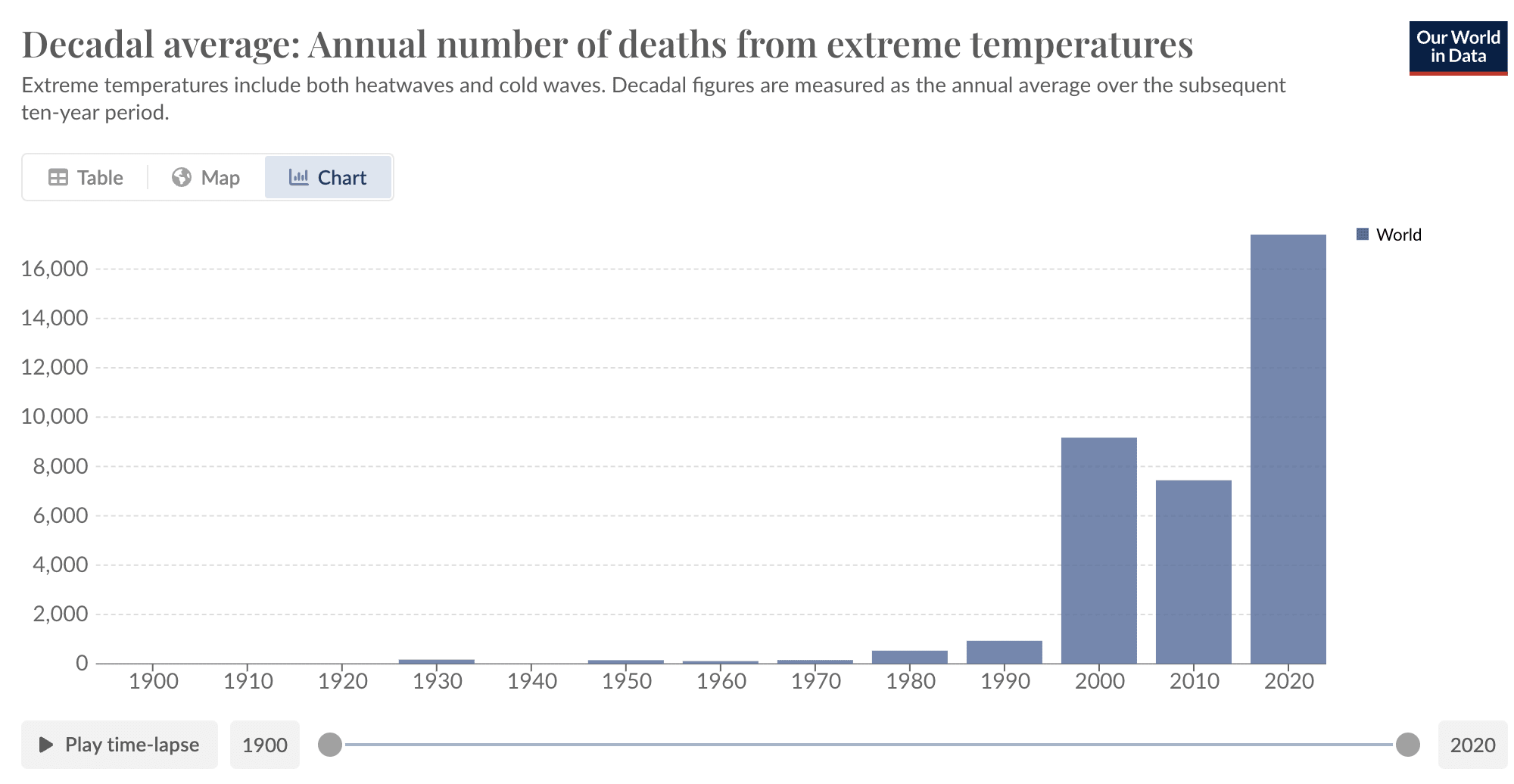

On top of this, looking at the specific kinds of natural disasters we’re discussing, it’s not clear they’re subject to the same downward trend, even on the decadal view. For instance, the OWID chart on natural disasters shows deaths from extreme temperatures have sharply increased in recent decades, and annual flood deaths have been fairly flat since the 1970s.

And just as a general point on the importance of climate-related extreme weather events, only counting fatalities may also give us a misleading picture, since it excludes other significant effects like damage to infrastructure, worsened mental health, and cumulatively huge economic losses. Again referring to the OWID page, the economic damage inflicted by natural disasters is much higher now than it was in the 1960s (as a share of GDP), despite them causing fewer deaths.

Our current view is that looking at the century-long average as an estimate of expected future fatalities may be an overestimate (primarily due to reductions in high-income countries), but it’s unclear that existing adaptation efforts will similarly continue to reduce harms going forward (or prevent potential rises in disasters where such are expected due to climate change).

The bottom line is we think there’s a lot of complexities in the analysis of the quantitative estimates, especially when adaptation and human response is a critical factor. But we believe that the areas we’ve identified are nonetheless promising areas to have a positive impact given what we know.