We live in a complex world with ever changing variables. When it comes to doing the highest impact activity it can seem impossible to be confident in one plan over another. Additionally, new information that comes from further research or even just time passing can make plan A seem better than plan B only to have it switch again the next day. This can cause some people to be lost in analysis paralysis or switch frequently between ideas, making little progress on each one. On the other hand, some people can pick a direction then never update again, constantly leaving impact on the table.

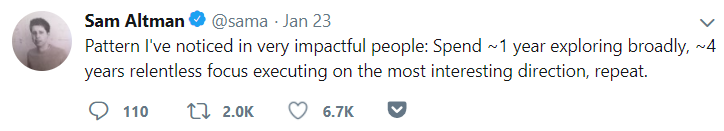

When I first entered the EA movement I was more the former, spending months on projects only to be convinced that something else was higher impact to work on before the project could be efficiently finished. Not falling prey to sunk cost fallacy, I would switch to the higher impact project and start afresh. Sadly, 10 half finished projects do not equal the value of a single finished project, and although I was always working on what I thought was highest impact at the time, this lack of staying power made the overall output over those years fairly low relative to what it could have been if I had persevered through the projects. Of course, it's also very easy and common to get stuck or committed into a project that is no longer the best choice and some people end up spending their career this way. So the real question becomes how to find a balance between those two. I think Sam Altman puts it quite well:

Although I think the specific numbers can be argued (perhaps it should be 6 months and 3 years) and for EAs generally our focus would be on the highest impact thing instead of the most interesting direction, I think the fundamental pattern is something I have also noticed. Using a strategy like this allows you to finish and mentally commit to large important projects. It also greatly increases the odds of a project coming to fruition. I expect a strategy like this will lead to far higher utility than a more intuitive strategy of “switch whenever you think something is higher impact than what you are doing” or “switch when something seems equally high impact but more exciting”.

Systematic exploring and choosing

Let’s dive into a bit more detail about what both of these phases might looked like. In the choosing phase you would want to be careful and fair minded, likely doing systematic research on a broad range of options to determine the top contenders. You would not want to psychologically commit to any idea but remain impartial during this phase.

You likely will find many competing options that look promising, although different in their relative merits. You then want to compare them carefully and get external feedback from other respected peers. This is the best time to get broad feedback as you are not committed to the project and you can directly show the comparison. You could ask a close friend or mentor if they think plan A or B is better and explain the merits of both. You friend could then answer honestly knowing that you have not already made the decision. People often won’t disagree with your plan if you’re already committed for fear of demotivating you or hurting your feelings.

The biggest enemy will be getting lost in analysis or being too quick to commit to a plan. Setting a specific amount of time for this research can greatly help both these concerns. Time capping is often necessary if you do want to make an endline choice because the truth is there will be very few occasions in project selection when you feel absolutely certain. At the end what you can hope for is making a well informed guess at the best option. And it’s important to learn not to eliminate all uncertainty, but rather develop the art of being confident you made the best choice you could have in the time available. On the other side of the coin, if you’re predisposed to jump into the first good idea that comes along, seeing that you’re only a fraction of a way through the time you set aside for research will remind you that you probably haven’t carefully considered enough of the alternatives.

Relentless focus

A common topic in EA is the idea of donation splitting. A less discussed topic is the idea of how to split time between projects. The concept of how much focus to have or how many projects to split time between has applications both personally and organizationally. Many people will put careful analysis into where they donate (even if it's fairly small amounts of money) but not apply the same rigour to volunteering or generally spending time on projects. This is particularly true for projects that are alluring and seem to have minimal time commitments.

Two common approaches I have seen I will term the 90/10 approach and the heavy focus approach. In this context the 90/10 approach involves spreading one's time over a wide range of projects and getting large amounts of benefit from minimal amounts of time. For example being on the board of many charities or having a full time job and doing several projects on the side. The heavy focus approach involves putting over 90%+ of your working time/energy into a single project (likely you full time job unless you are a student or doing E2G). An example of this might be a staff of an EA organization who does not do any major projects on the side and instead puts more time/energy into working more hours for the organization.

Over time I have become more positive towards the heavy focus approach and less positive towards the 90/10 approach for most EAs, despite continuing to value it in many other topics such as research. One piece of evidence that updated me in this direction was the endline results of individuals that have been focused compared to individuals who have been more spread out. I have found that individuals who spread themselves across many projects tend to have projects slip through the cracks and end up spending time on projects that after a comparative analysis would not compete with the top thing they are working on. When I compare these people to people of seemingly similar abilities but who have a much tighter focus I tend to find they end up with much larger success and not a proportionally lower number of success.

There are a few possible reasons this could happen. I think there is a heavy cognitive cost of switching your mind between very different projects, leading to less deep and creative thinking than you would expect given the split of hours. Generally part time workers have a harder time making major contributions to an organization and the same principle would seem to hold true between working more or less hours as a full time employee.

A second possibility is that smaller projects tend to be hit harder by planning fallacy than large ones. If I expect it to take 3 years to start a high impact charity often that has ended up taking 5 years but for many small projects that are high impact, presuming they will only take 10 hours ended up taking orders of magnitude more time than expected.

Another possibility is that many of the most worthwhile projects are really difficult and require full time attention to have a good chance of being done successfully. To use a personal example, most of my time is spent working on Charity Science Health, a direct poverty charity that is aiming to be GiveWell recommended. This project is sufficiently challenging that our odds are under 50% of being successful, even with almost all my time and energy going into the project. I think founding other charities or for-profits are often similarly challenging, and most of the very worthwhile projects also come with very high levels of difficulty and time commitment.

Plan re-evaluation points

An important concept I often talk about to people starting new and ambitious projects is the idea of plan re-evaluation points. With many ambitious projects, some days your project will be going great and you will feel great about it. During other days it will take all of your energy just to stay positive and everything will feel like it's falling apart. Days like this will come and go for even the best projects. It's great to think carefully about your project’s impact but if, as an EA, you are constantly re-evaluating your project, it will be hard not to abandon it on a hard day/week/month. The solution I propose is set “plan re-evaluation points” where you review your project and plan with fresh eyes and look over all the data you can to see if this project is still worth doing. I think how often to do these varies a bit depending on how long you been on the project. It might start as once every 6 months but move to longer periods until its once every 3 years. These plan re-evaluation points can allow you a deeper level of focused without sliding into questioning your whole project while still ensuring you can update appropriately based on long term trends and evidence. The real trick to be able to hold off between plan re-evaluations is having strong confidence in your initial choosing phase such that you know you made a good call. This system can save a lot of pain and also increase the chance you stay on your project long term.

In summary:

- Spend 1 year choosing and 4 years relentless pursuing a project.

- In the choosing phase, be careful, broad, systematic and uncommitted.

- In the choosing phase, pick the best option you can in the time you have given yourself.

- In the focus phase, avoid other projects that might seem like easy wins but will sap your time and energy.

- In the focus phase avoid major project re-evaluation until set points.

Following these steps I think you can end up with a much higher impact career where you can make major progress on important projects.

Just commenting to express my agreement with this.

I've been thinking about this in my own life my recently. I realised I was spending a lot of time reflecting on the effectiveness of my current projects and this was getting in the way of actually doing them. I also came to the conclusion I should stifle my doubts, get to the end of what I'm doing and then reflect on changing direction.

I'm not convinced by the 1:4 rule, but the general idea seems good.

I have often fallen prey to over-negating the sunk cost fallacy. That is, if the sunk cost fallacy is acting as if you get paid costs back by pursuing the purchased option, I might end up acting as if I had to pay the cost again to pursue the option.

That is, if you already bought theatre tickets, but now realise you're not much more excited about going to the play than to the pub, you should still go to the play, because the small increase in expected value is available for free now!

I don't think that this post is only pointing at problems of the sort above, but it's useful to double check when re-evaluating projects

It would also be useful to build an intuition of what the distribution of projects across return on one's own effort is. That way you can also estimate value of information to weigh up against search costs.

I have another possible reason why focusing on one project might be better than dividing one's time between many projects. There may be returns to density of time spent. That is, an hour you spend on a project is more productive if you've just spent many hours on that project. For example, when I come back to a task after a few days, the details of it aren't as fresh in my mind. I have to spend time getting back up to speed, and I miss insights that I wouldn't have missed.

I haven't seen much evidence about this, just my own experience. There might also be countervailing effects, like time required for concepts to "sink in", and synergies, or insights for one project gleaned from involvement in another. It probably varies by task. My impression is that research projects feature very high returns to density of time spent.

Returns on density of time seems pretty plausible to me and particularly for cognitively intensive projects. Regarding sink in effects, I suspect many of these benefits can be accomplished by working on different aspects within the same overall project. E.g. working on hiring to take a break from cost-effectiveness analysis work when founding a charity.

Why is "spreading one's time over a wide range of projects and getting large amounts of benefit from minimal amounts of time" called "the 90/10 approach"?

https://betterexplained.com/articles/understanding-the-pareto-principle-the-8020-rule/

I did not coin the term. I have heard quite a few EAs talk about the 90/10 principle. I was using it in that context. The idea is you can get 90% of the benefits of many projects with only 10% of the effort.

I wonder how much the "spend 1 year choosing and 4 years relentless pursuing a project" rule of thumb applies to having a high-impact career. Certain career paths might rely on building a lot of career capital before you can have high-impact, and career capital may not be easily transferable between domains. For example, if you first decide to relentlessly pursue a career in advancing clean meat technology for four years, and then re-evaluate and decide that influencing policymakers with regards to AI safety is the highest-value thing for you to do, it's probably going to be difficult to pivot. There's a sense in which you might be "locked in" to a career after you spend enough time in it. My sense is that, for career-building in the face of uncertainty, it might be best to prioritize keeping options open (e.g., by building transferable career capital) and/or spending more time on the choosing phase.

I am more skeptical about transferable career capital. I tend to see people doing impressive things even in unrelated fields as providing a lot of career capital. E.g. A lot of EAs would hire someone who had done a successful project in another EA cause vs just doing something less related but more transferable. E.g. going into consulting.

Also generally in line with the argument above, I tend to see that doing great focused work leads to better outcomes than “building generalized career capital” with the idea of eventually using it in a high impact direction. The most common outcome I see with EAs doing that is them spending a bunch of time saving/building career capital and then them leaving the EA movement, having caused pretty minimal good in the world. Additionally, doing impressive things in the EA movement is a way to both build career capital and do good at the same time.

That being said, I think it’s somewhat a different question of what to factor in. You might decide after one year that the best thing to do is X (e.g. get a degree) which sets you up better for your next plan revaluation point 4 years later with minimal re-evaluation until you have gotten your degree.