Mark Fabian and I recently had a debate at EA Global London: 2023. In it, we discuss taking happiness seriously: Can we? Should we? Would it matter if we did? We both really enjoyed doing this. We don't think EAs think enough about well-being or debate enough in general, and we hoped our discussion was a way to bring out some of the issues. We only regret we could get stuck deeper into the topic (and I only regret that couldn't get the clicker working...).

(You can see the slides for this talk here and here.)

Taking happiness seriously (Happier Lives Institute)

Let me start you with a real-life moral dilemma. For £1000 you could double the annual income of one household living in absolute poverty. You could provide 250 bed nets, which would save in expectation 1/6 of a child's life or 1/6 of your child. You could treat 10 women for depression by providing a 10-week course of group therapy, or you could do over 1000 Children. And of course, what we want to do is to do the most good. But the question is, how do we know that we're doing that?

Two paths to measuring impact

I want to point out there are really two parts to measuring impact. The first is what I've called the objective indicators approach, which I think is just sort of the default approach that society has taken for the last 100 or so years. To think about impact, we look at objective measures of well-being, such as health and wealth, and then we make intuitive trade-offs between them. An example of this is GDP. That's our default measure of social progress. More economic activity is good.

However, the objective indicative approach seems to miss something. It seems to miss people's feelings, their happiness, and how their lives are going for them. Where is that in the picture? An alternative, then, is the subjective well-being approach where we use self-reported measures of well-being such as happiness and life satisfaction. The typical case would be 0 to 10. How satisfied are you with your life nowadays?

And so my proposal in this session is that we should take happiness seriously. We should set the priorities using the evidence on subjective well-being trying to work out.

You might wonder, is this a new radical idea? Well, the first steam train, the Coalbrookdale Locomotive, was built in 1802. And the idea that we should take happiness seriously is as old as that. Thomas Jefferson, writing in 1809 said, “The care of human life and happiness is the first no legitimate object of good government.” Jeremy Bentham, writing in 1776 said, “The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.” And looking further back, you have Aristotle who said, “Happiness and meaning and the purpose of life is the whole end and aim of human existence." This idea is old. It's older than the steam trade. It has real lineage to it.

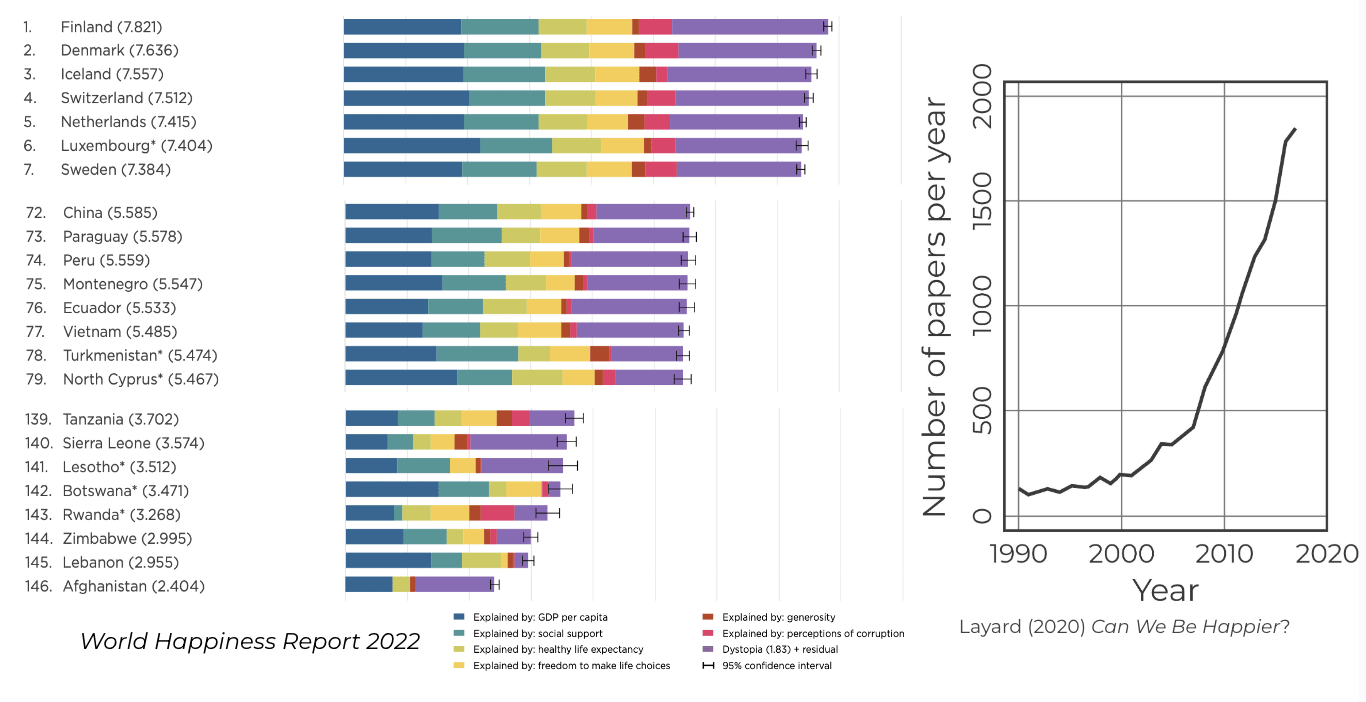

What’s new? Data

But what is new is that now we have data. It was only after the Second World War there started to be large-scale surveys of households on how their lives were going. Gallup was founded in 1946. It was in 1972 that there are two countries started having nationally represented examples of subjective well-being. The US General Social Survey, the Gross National Happiness Index in Bhutan. And in 2005, there's the first global survey on well-being. There's the Gallup World Poll, which runs in 160 countries and surveys 98% of the world's population. In 2011, the UK starts to collect and measure data on well-being. The UK is kind of weirdly enough a world leader in measuring well-being. You’ll hear more of that later. In 2012, there was the first edition of the World Happiness Report. People know that the Scandinavian countries are the happiest. But in fact, it's only been 10 years that this survey has been running. That's just how recent this is. In 2022, the UK's Treasury publishes a framework for how to do policy appraisal in terms of well-being - not just in pounds and pence, but how to do it in terms of well-being. And now, there are 20 countries around the world where the national governments collect and measure well-being. This started not too long ago, and now it's really gathering steam.

We now know quite a lot about what happiness is, how to measure happiness, and what drives it. But what I don't think we know so much about is what the priorities are. So this project of taking happiness seriously hasn't yet really taken off.

I started looking into this when I started my PhD in 2015 and I found myself I really believed in the ideas of effective altruism. We should do the most good we can with our resources. But I also thought that we should take happiness seriously. We should look at the research on subjective well-being, and we should bring them together. They seemed like two obvious ideas that should be combined. And I was surprised to learn that, as far as I could tell, no one really seemed to have done this before. And that was the kind of project I got started on.

Now, in retrospect, maybe I shouldn't have been so surprised. I think it would have been difficult to do it really much earlier because just there wasn’t really any evidence available. But now there is.

There are two projects to think about here. There's the direct impact project. How can we use happiness research to find better marginal funding opportunities? And then the big scale, the moonshot is thinking about how can we engineer a paradigm shift so that when societies think about social progress when philanthropists and policymakers are thinking about measuring what they do and having an impact they put well-being at the heart of that. And because we spend an enormous amount of resources around in our societies trying to find ways to improve people's lives, then to spend this a little bit better would have an enormous impact. I think we can probably spend it quite a bit better.

The case for taking happiness seriously

Hopefully, that has many of you on board. But now let's get into a little bit more detail. There are three parts to taking happiness seriously.

- Happiness matters.

- It can be measured by asking people how they feel.

- Our predictions about happiness are often wrong.

Of these, I think I won't need to do too much to convince you of the first. The second and the third ones I might need to do more on. And so y overall suggestion is that we should take happiness seriously. We should set priorities using the evidence on subjective well-being. And I want to flag here that when I talk about increasing happiness, I'm not just about making happy people happier. This is about reducing misery as well. In fact, that's probably where the priorities lie.

1. Happiness matters

First, happiness matters. Let's go right back to the start and ask, “Why does happiness matter?” Well, well-being definitely matters. And well-being is a term used in philosophy to refer to what ultimately or intrinsically makes your life go well. And wealth and health, which we usually understand as being instrumentally good for well-being. We want to be richer, not just because being richer is good but we want to be richer because we think that will improve our well-being.

So now we can ask, “Well, OK. We care about well-being, sure. But what is well-being?”

Philosophers have three theories of well-being. This comes from profit, the canonical list. One is preference satisfaction. Your life goes well, to the extent that you get what you want. The second is hedonism. Your life goes well, to the degree that you're happy. You have overall positive experiences. And the third is the objective list. There's more to life than happiness and desires. Maybe there are some more objective things such as love, knowledge, success, and meaning.

I don't think I don't need to convince you that happiness is the only thing that matters to convince you that it matters. You don't need to be a hedonist, to be concerned about this. Everyone thinks that happiness matters to some extent. And if you didn't think people's suffering, that their misery was some part of your moral theory, then I think that would be absurd. Monstrous. I think you'd really have missed the point about what ethics is about. Yet standardly, when we put our priorities together, we don't tend to kind of directly account for the human experience in doing that.

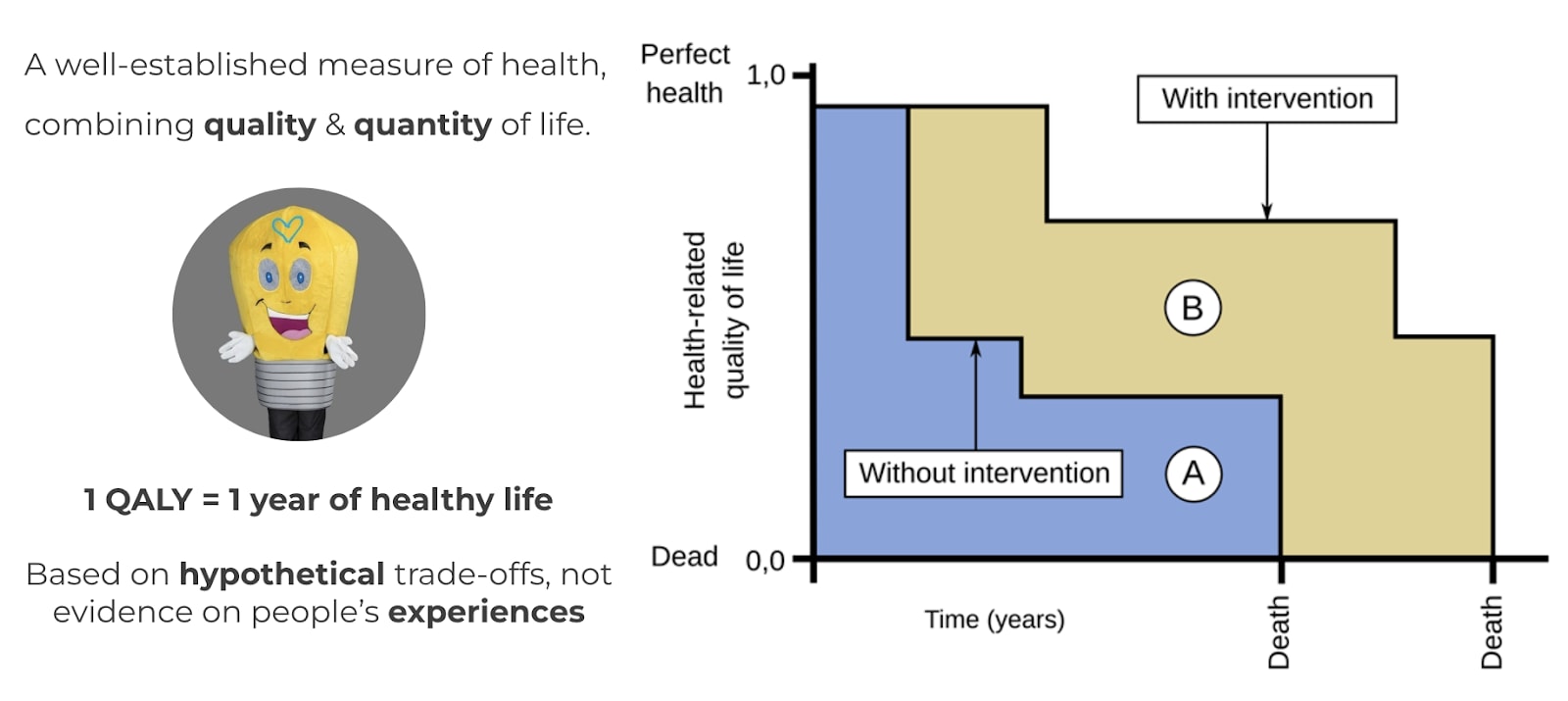

QALYs (Quality-Adjusted Life Years)

How do we do this? Well, one way, which is really common and you're probably very familiar with is the quality-adjusted life year. It's a way of measuring the quality and quantity of life. The way these numbers are constructed is that people are asked to engage in hypothetical trade-offs. How bad would it be if you lost your leg compared to living a certain number of years in perfect health? But the problem with these is that they are asking people to make predictions about what they would choose about experiences they haven't yet had. And one thing we probably really want to know is how bad is it if your leg falls off. How does that really affect your well-being as you live it? And that's the bit that is missing out on QALYs and disability-adjusted life years as well.

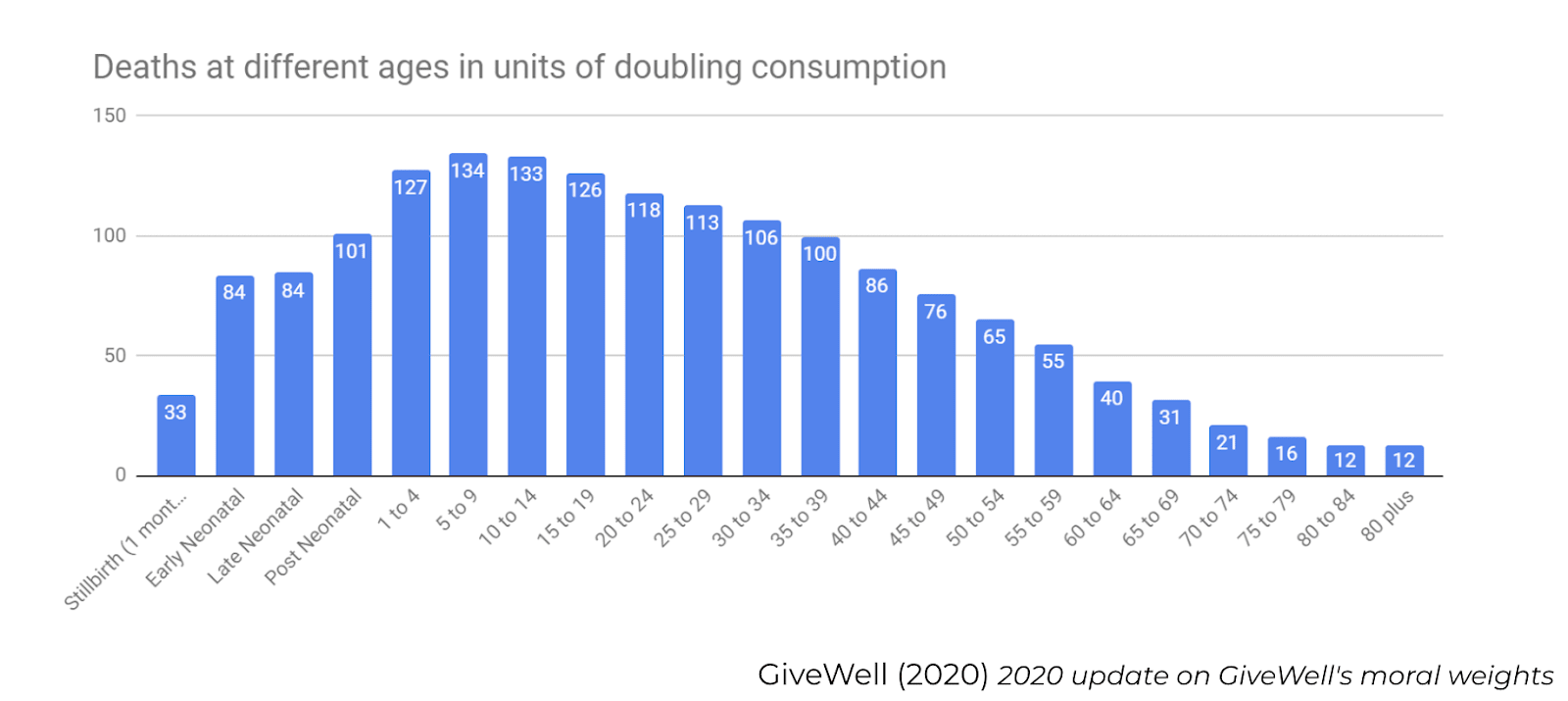

So this approach in taking the objective, in this case, approach is common outside of effective altruism. It's kind of been the work course within it. This is how GiveWell has been doing things - looking at years of doubled income and comparing that against the value of a life saved. And I don't want to kind of beat up on GiveWell here, they've done an enormous amount of amazing work. I find what they do really inspiring, and they're using the sort of objective measure measures which are just kind of common in society. But I think we can we can do better. There are now better methods that we can use, and we should move to those.

2. Happiness can be measured

A response to this is, “Well, okay fine. I guess we do care about happiness. But, you know, we're gonna have to stick with these objective things because we can't really measure it.”

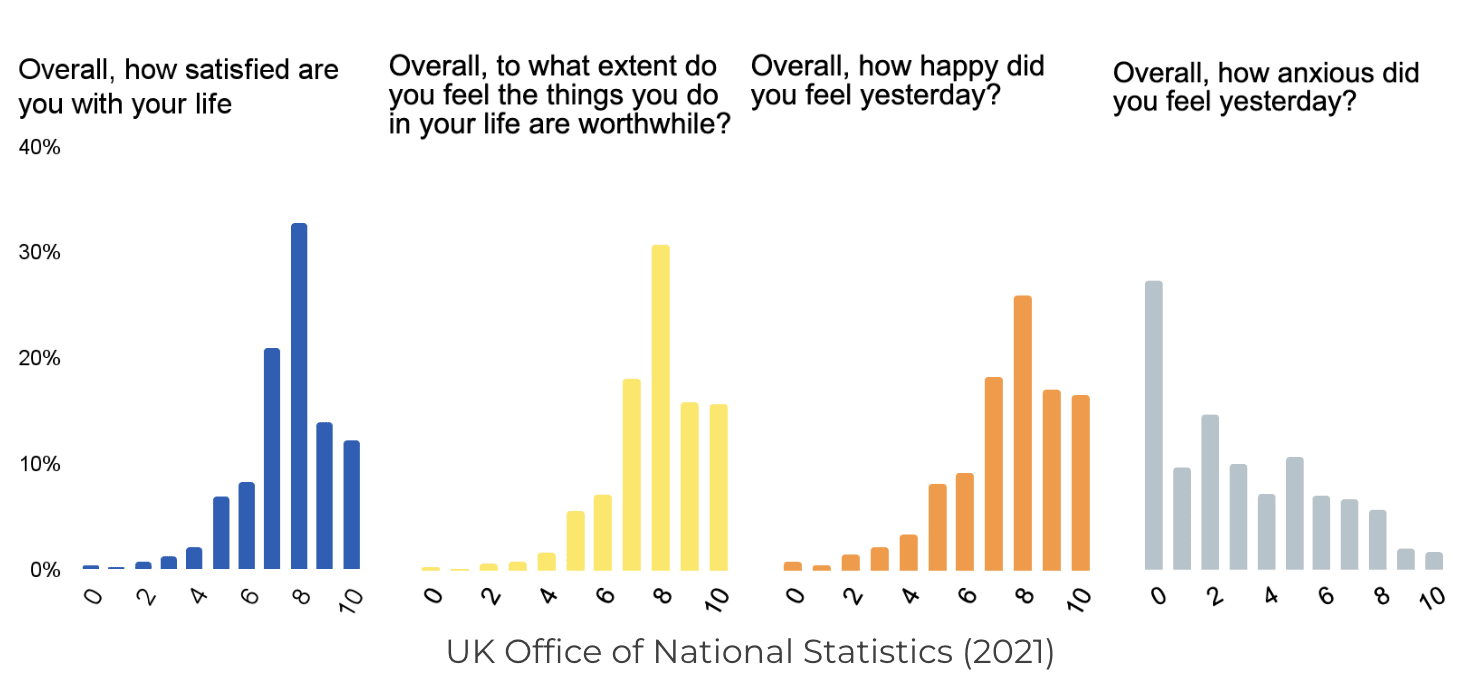

And so my response is, “Well, we can.” The Office of National Statistics in the UK. This is how we do it here. There are four questions that are asked about 300,000 people a year.

- Overall, how satisfied are you with your life? And you can see from this that about 33% of people say that they are eight out of 10.

- To what extent do you feel things in your life are worthwhile?

- How happy did you feel yesterday?

- How anxious did you feel yesterday?

You can see that the anxious one is sort of reverse-coded and you could also see that there's sort of a similar pattern here. These different questions pick out different elements of well-being, but they're giving us kind of broadly the same result.

The suggestion, then, is that we should replace the Objective Indicators Approach with Well-Being Adjusted Life Years, WELLBYs. What's a WELLBY? A WELLBY is a one-point change on a 0 to 10 scale for one year. It’s just sort of the same idea as the QALY, but we're just measuring something different.

You might think, “What' happened? Why did people start to think that measuring people's feelings was a sensible thing you could do? Isn't it also the objective? How would you know?”

The way that you test these things is by seeing how they behave in the world, and what their associations are. Research into well-being, there's now been lots of it because people have been skeptical that you can really rely on this stuff. So the sort of thing you find is that the highest happiness and life satisfaction are associated with higher income, higher self-reported health, and being in a relationship. There's a correlation between what you say and what your friends about you, how often you smile, and that happier and more satisfied people are less likely to commit suicide. This is telling us, really, that if you want to know how happy people are, asking them “How happy are you?” is actually a pretty good way to find that out. It's sort of deceptively simple.

The alternative to this, to kind of maybe beat up slightly on The Economist, is that if you want to know how someone's life is going, if you wanted me to know how your life was going, would you rather that I asked you “How are you feeling?” or would you rather I looked in your wallet? Or if saw if you're employed? That sort of thing. It seems like we really want to know what people say about their own lives. That's how we communicate normally. And that's what we should expect when we do our prioritization.

You might wonder how much we can trust this stuff in an international setting. This is from the world happiness report and you can see that the Scandinavian countries are at the top with an average of about 7.5 out of 10. Put some middle countries here. And then the bottom, you see countries like Zimbabwe and Afghanistan around 2.5.

I think this is quite reassuring and this is part of the reason why there's been such an increase in research in this. People have thought, “Yeah.OK, this is what we care about. It turns out we can measure it. OK, let's see what we can find. So I think this is now taking off.

Challenges with happiness data

There are, of course, some challenges with happiness data. With data quality, one question that I spend lots of my time talking about is, “Can we really trust happiness data?” I did this as one big topic in my PhD.

One question you would ask is, “Are the scales linear? Is going from a four to a five, the same as going from an eight to nine?” Another question is about comparability. “Is your seven out of 10 the same as my seven out of 10?” Questions of data availability, particularly in low-income countries. So if you want the survey data, but it's not there. What do you do?

And then there are questions, I've called these data interpretation, but you might think that these are just sort of straightforward moral philosophy questions. You've got happiness and you've got life satisfaction. If they differ, what should you choose? How do you trade them off? What do you think about trading off increasing quality of life against quantity of life? I think these aren't unique challenges. I mean, whatever you measure, you're going to have some issues with it. I think the issues here are not obviously much, much worse than they would be if you were taking the alternative approach.

The overall flavour of response to this is to say that I think we should think something similar about the well-being approach that Winston Churchill said about democracy, “It's the worst method apart from all the others that have been tried.” We shouldn't let the perfect be the enemy of the good here. There's some really useful information we can gather, which currently we're not making that much use out of.

3. Our predictions about happiness are often wrong

The third bit is that our predictions about happiness are often wrong. We care about this, we can measure it, but you know, why bother? We were just getting it right at the moment. And the kind of boring but obvious claim here is one of the ones which was the genesis of effective altruism: Toby Ord, comparing different interventions in global health measured in terms of disability-adjusted life years, which is sort of a sister of QALYs. He found there's a really big difference between the best things and the things which are good. We don't know in advance what they are, so we should do research. Hopefully, the idea that we might be wrong and we should find out and look at the evidence is not too much of a hard sell.

That's not particularly informative. We could be wrong, but like, how could we be wrong? And I think the interesting research and perspective here is from the psychological literature on Failures of effective forecasting or miswanting - How do we get it wrong? And to cut a long story short, the story here is that we're generally pretty good at whether things are good or bad, but we're not very good at predicting how good or bad they are and for how long they're going to affect us. You know that being dumped is probably bad, but what you might get wrong is how bad that is and how quickly it will take you to get over it.

One sort of particular source of bias and explanation is focusing illusions. When you're imagining what it's like to be someone else, you pick up the bits which are kind of easier to imagine, easier to visualize. So if you are imagining someone really wealthy, you're imagining what it would be like to be a billionaire. Then you're probably not accounting for what it's like for that person once they've got used to it and then just kind of living their ordinary life. Of course, this raises the question. Well, OK, have we got the priorities wrong? It might just be that there's a bit of bias, but a bit of bias might not be enough to actually change what we're doing. And that's actually what got me looking into this during my PhD.

Here's a picture of me giving a talk at Effective Altruism Global in 2017, full of youth and vigour before effective altruism stripped it out of me. At that point, I was committed through my PhD. And I'm sort of speculating - well, we take this happiness seriously stuff here. I'm talking about pain and mental health. I talk about the possibility of using psychedelics as a way of treating mental health which certainly has picked up. But really, then I was speculating. I said we should look into this and see what we find. Lots of people thought this was mad. This was a waste of time. But fortunately, there were a few donors who who who backed me and thought this was sensible.

But, does it matter? HLI investigates

And so, as a result of this, I was able to set up the Happy Lives Institute and actually do the work and investigate. We're a small team. We don't have Open Philanthropy funding yet, but we're working on it. And I really want to thank particularly my two colleagues, Joel Maguire and Samuel Duprey, who have worked on this so tediously for the last few years and really kind of allowed this to happen.

The plan when we started was to reassess in terms of well-being adjusted life years the sort of canonical EA recommendations to see if taking happiness seriously would change the priorities. A sort of proof of concept. We compared four interventions: cash transfers, treating depression, deworming, and bed nets. Three of those four are sort of part of the familiar list, and treating depression is new, and we wanted to see how it would stack up. At the end of 2022, we completed that, and we thought we concluded that it does.

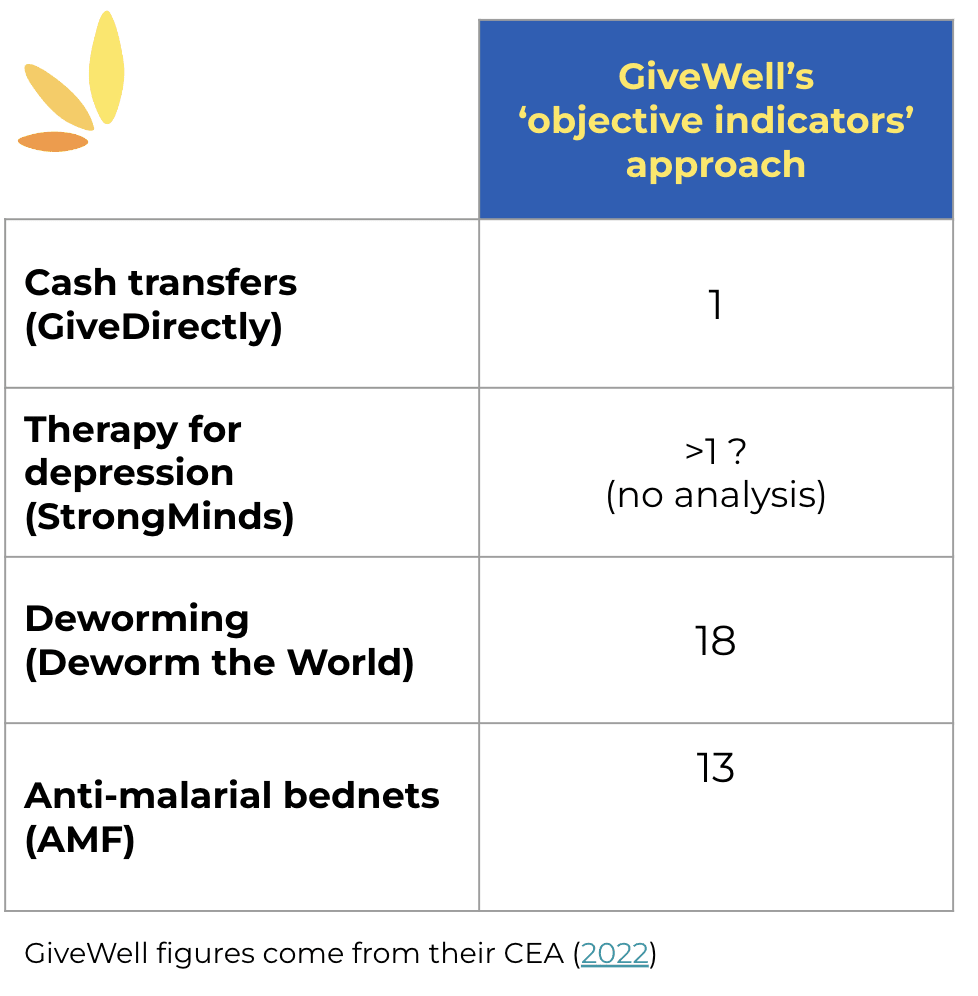

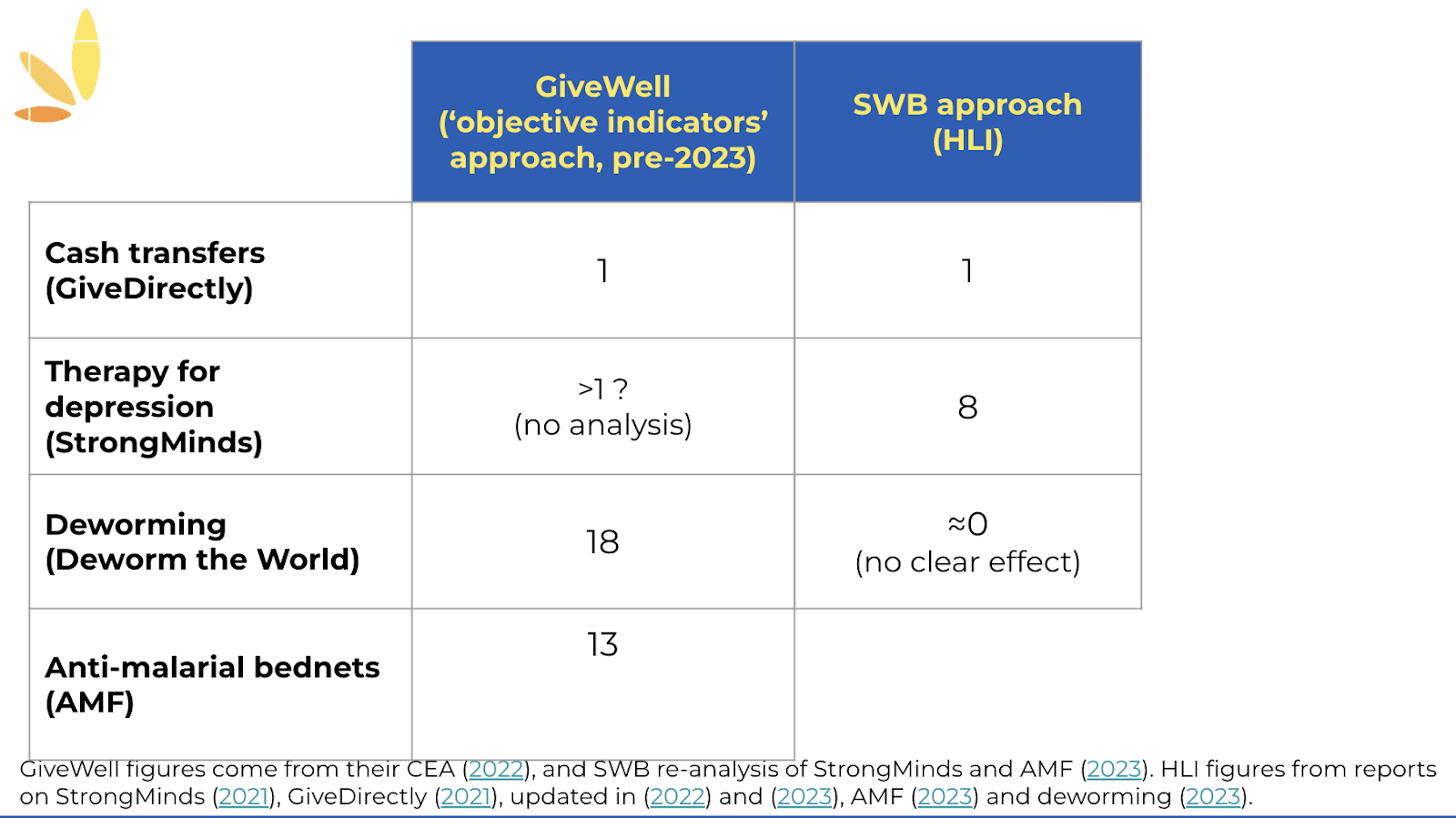

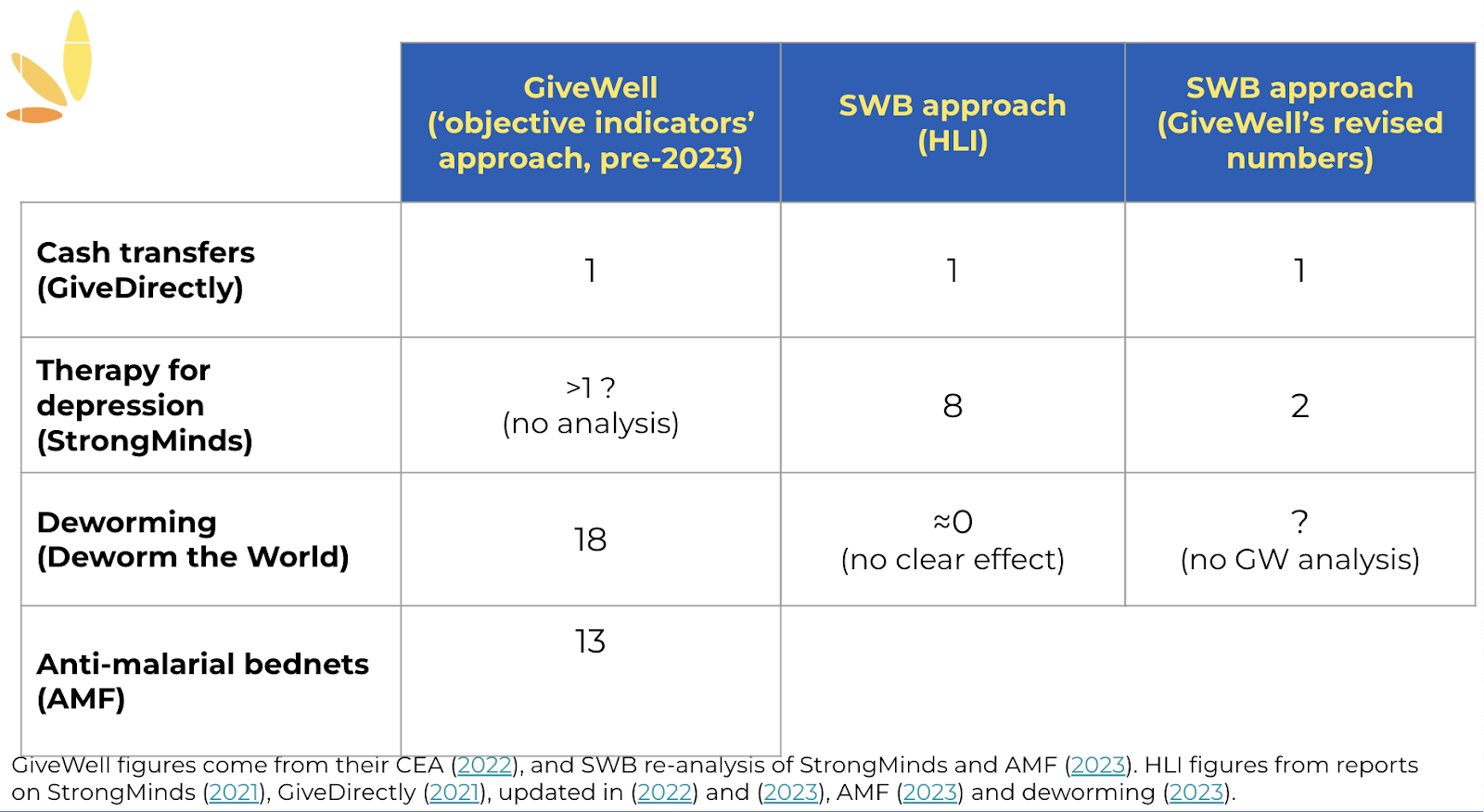

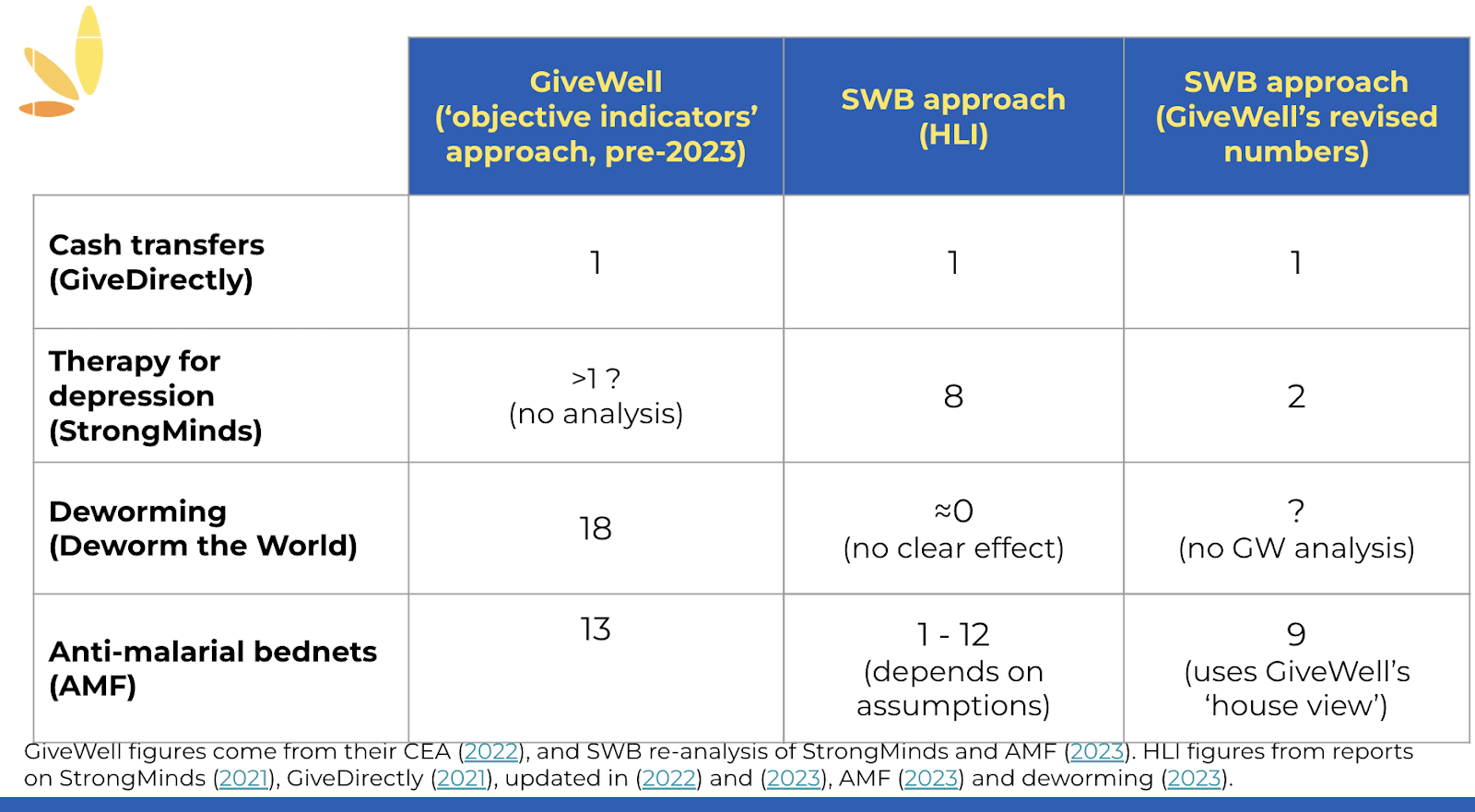

Let me very briefly tell you about our research results. We did lots of work on this. I can't go into the details. I'll just be going to give you the highlights. If we're thinking, how does this change things? Then we need to start with the existing views. I'm taking the cost-effectiveness numbers from GiveWell. This is in comparison to cash transfers. GiveWell hadn't had an analysis on treating depression with therapy. So presumably, it's less cost-effective than cash transfers or anything else. Deworming the world, about 18 times better, and anti-malarial bed nets about 13 times

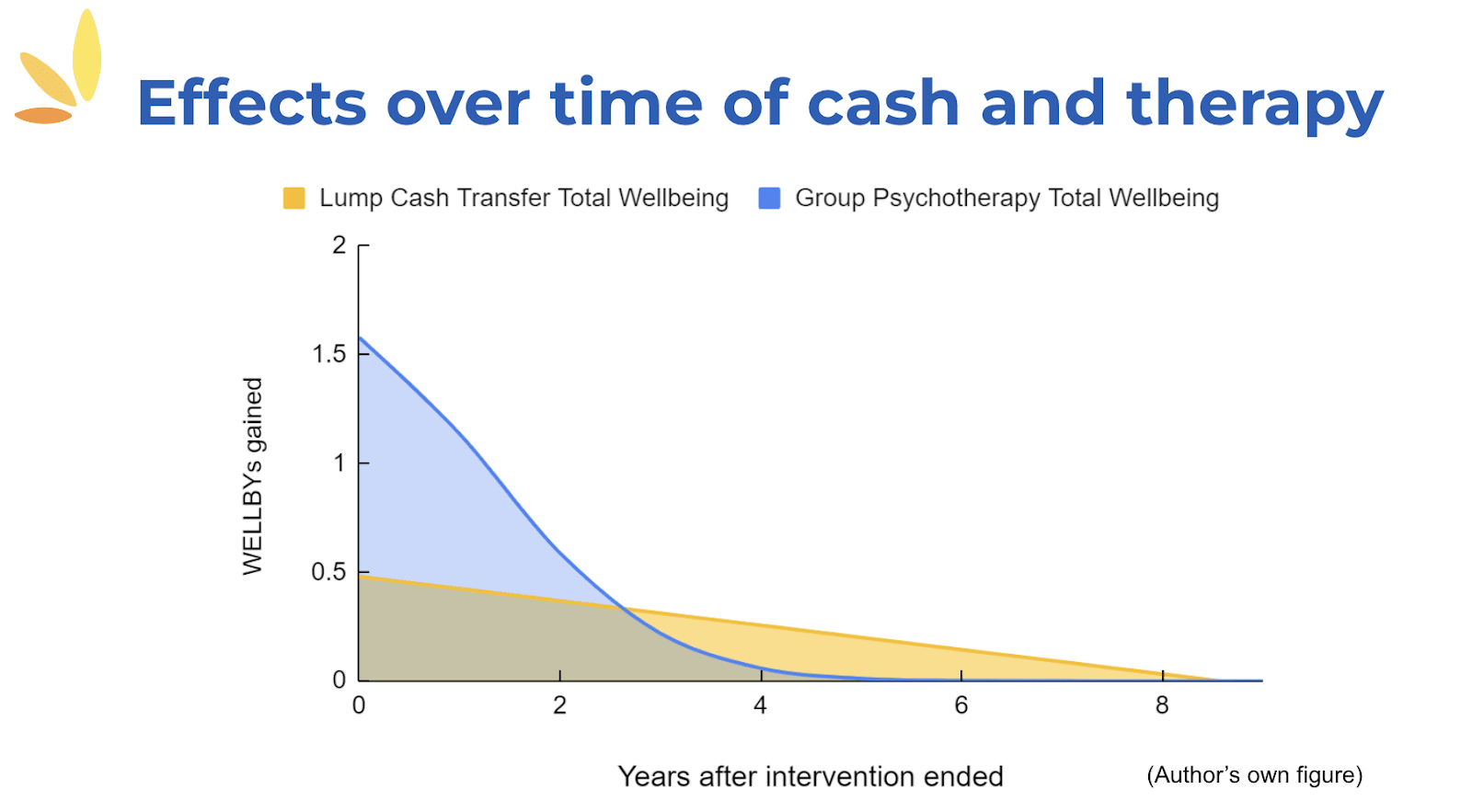

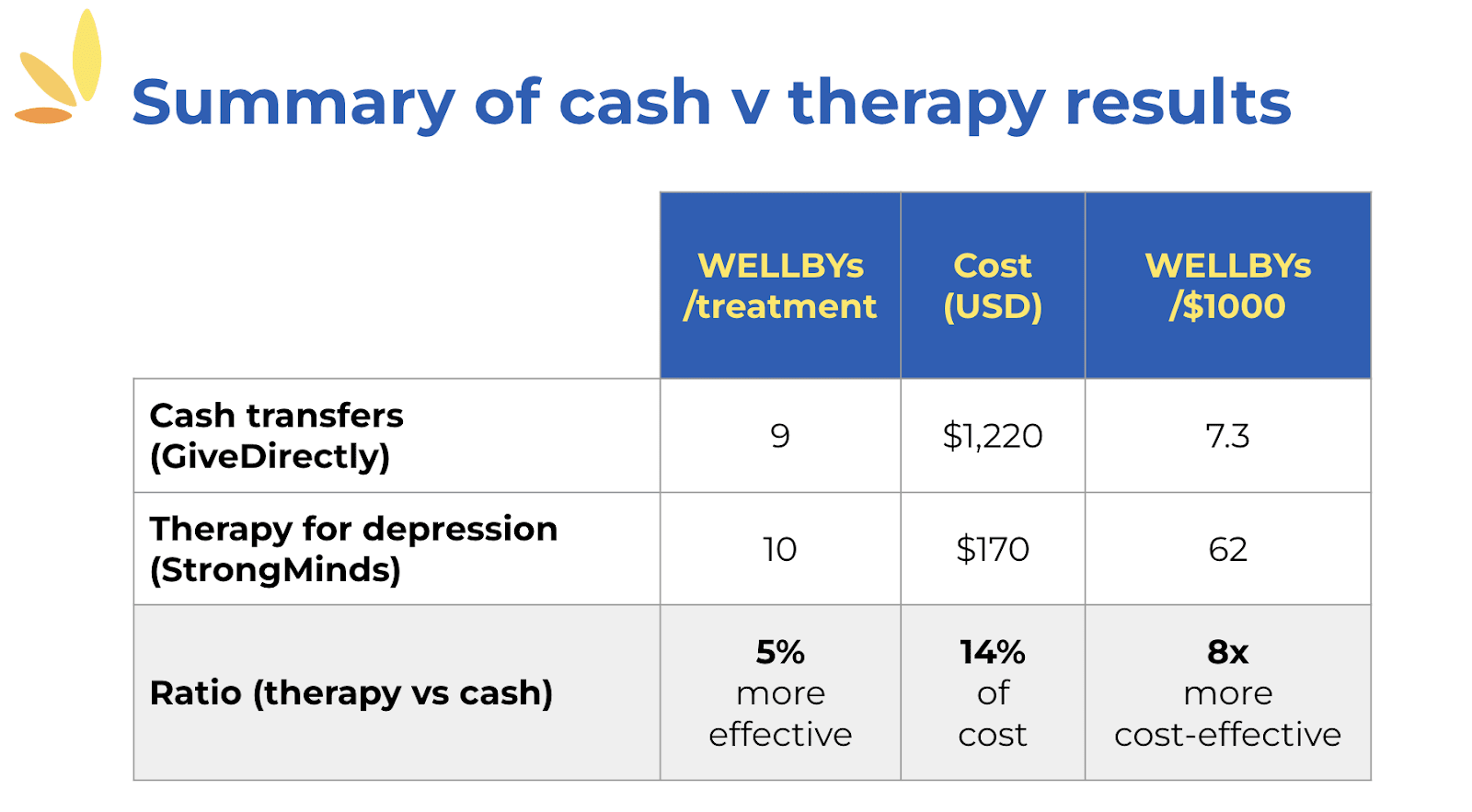

Let me tell you about what we found. That's the background view. What do we get to? How does that change? We looked at cash transfers and group therapy for depression. We did a meta-analysis of each. We looked at the available studies. We had about 140,000 people total across both. So we really tried to look at all the available evidence that was there. We did some kind of technical jiggery-pokery to convert it into well-being scores. And what we found was that the $1000 cash transfer has about the same per-treatment effect as group therapy for well-being. You can see that the cash transfer does have an effect, has a much longer lasting effect. But the effect of treating depression is larger, but it fades sooner.

So the effects are about the same. But, if you're delivering a $1000 cash transfer, it costs you a bit more in total to do that. And then treating depression is about a $100 to $150 per person. And so what drives the difference is the cost.

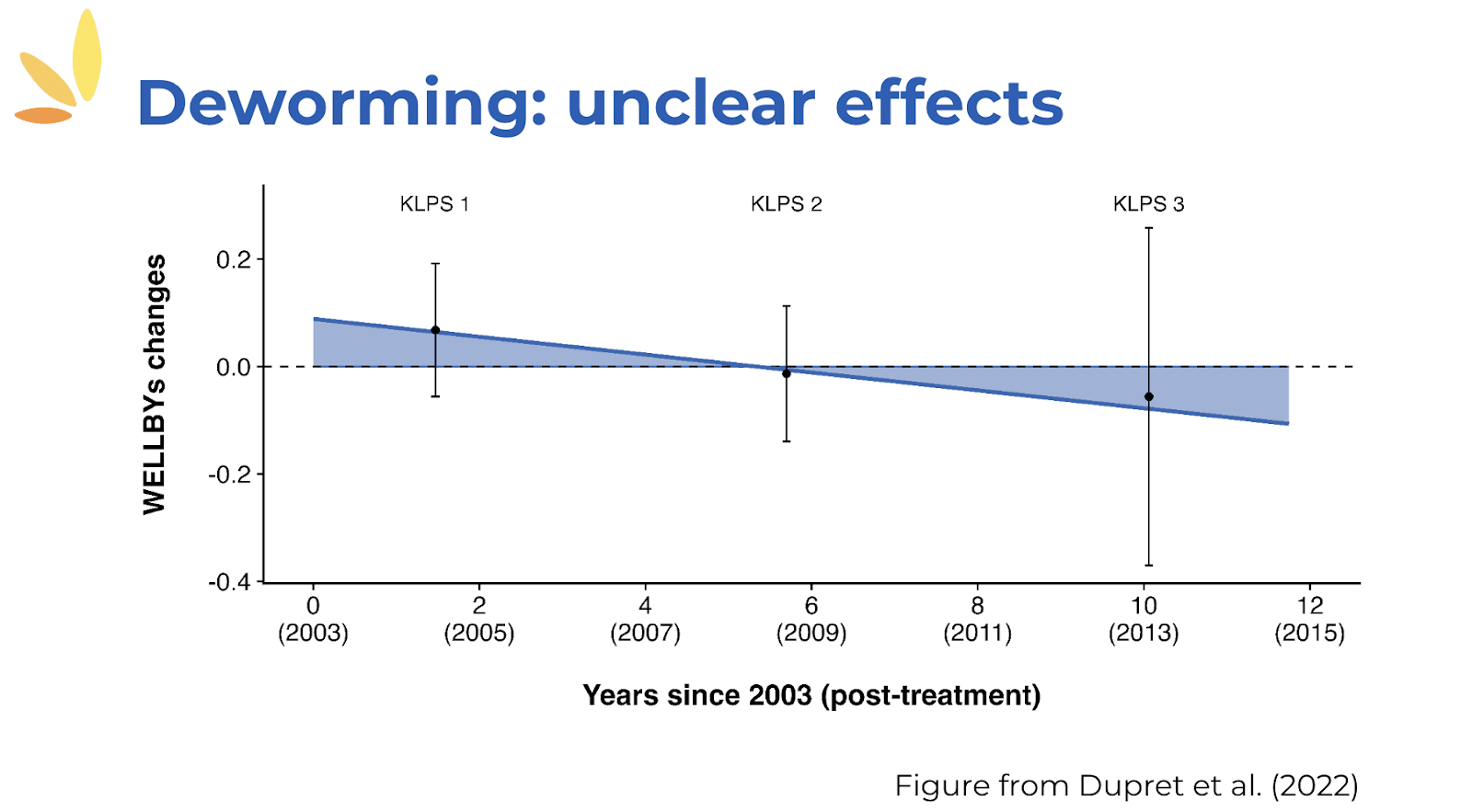

At the end of last year, we looked at deworming. There have been open questions over whether deworming has a long-term effect. We looked at one study that people are familiar with, that GiveWell and other people use to track the effects of deworming over time. There was some happiness data in there which it turned out no one else had looked at. And so this is the effect of deworming over time. You can see that they're not statistically different from zero. And if you take these very seriously, then you conclude that deworming is making people worse off. So we just assume that there are no clear effects here, which is, like, I say, consistent with this kind of wider picture. It's unclear how much long-term effect there is.

And of course, the point of a happiness approach is that let's say you have your deworming that should change your life in]n some ways. You should pick up those changes and then the changes in people's life circumstances should be reflected in their self-reports. That's what we see with the rest of the literature. If it makes a difference, you should see it.

Here's what we get through the subjective well-being approach. We found cash transfers are a factor. That's the benchmark. We find that therapy for depression is about eight times more cost-effective. That's like the really big result because that hadn't been featured in our understanding before. But taking a well-being approach allows us to measure that and to find it. We're not so sure about the effect on deworming.

Accounting for uncertainty

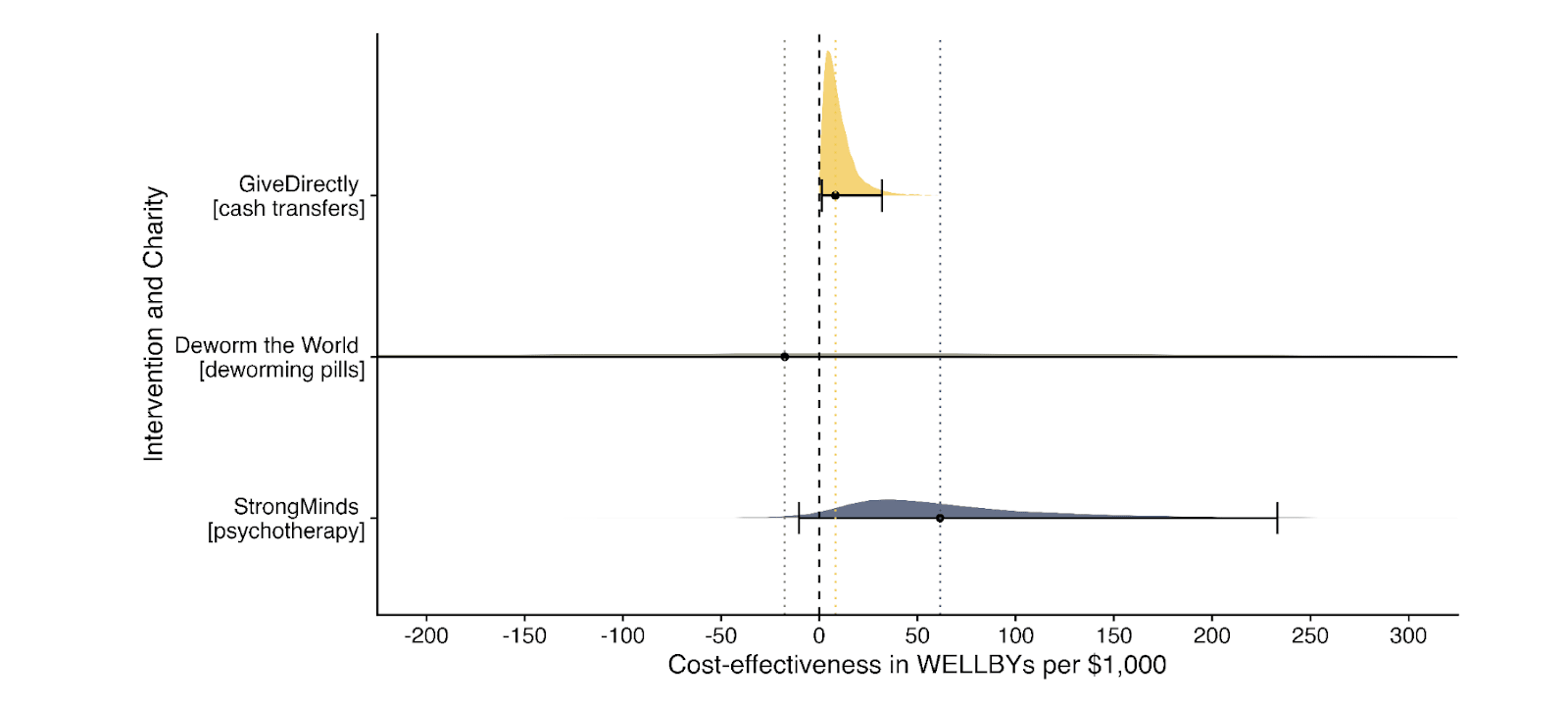

I've just given you the overall numbers. But then there's lots of uncertainty here and we've tried to model that. The line in the middle is deworming - the fact that just represents that it's a very cheap intervention with an uncertain effect. The distribution is really large. So, that's how got to our results for these different quality-of-life interventions.

Givewell has also, just in the last couple of months, looked at our numbers and they formed their own view. GiveWell's conclusion was that therapy for depression is about twice as good as cash transfers. I want to say three quick things about this. First, it's I'm really, really delighted that GiveWell took an interest in this and they thought, OK, this well-being approach is reasonably sensible. Secondly, I think it's significant that even on the sort of more sceptical view that GiveWell ended up taking, it's still twice as effective as cash transfers. So there's a real agreement here that we're finding something new when we're looking at improving quality of life. And thirdly, overall, we didn't find much reason to update in result of GiveWell’s analysis. What the GiveWell researcher had done is look at the bits of evidence and say, I'm not quite sure about this. So our response to this was that we didn't actually think there was strong evidence provided that that that should merit those reductions.

Comparing life-extending (bednets) versus life-improving (cash, therapy, worms)

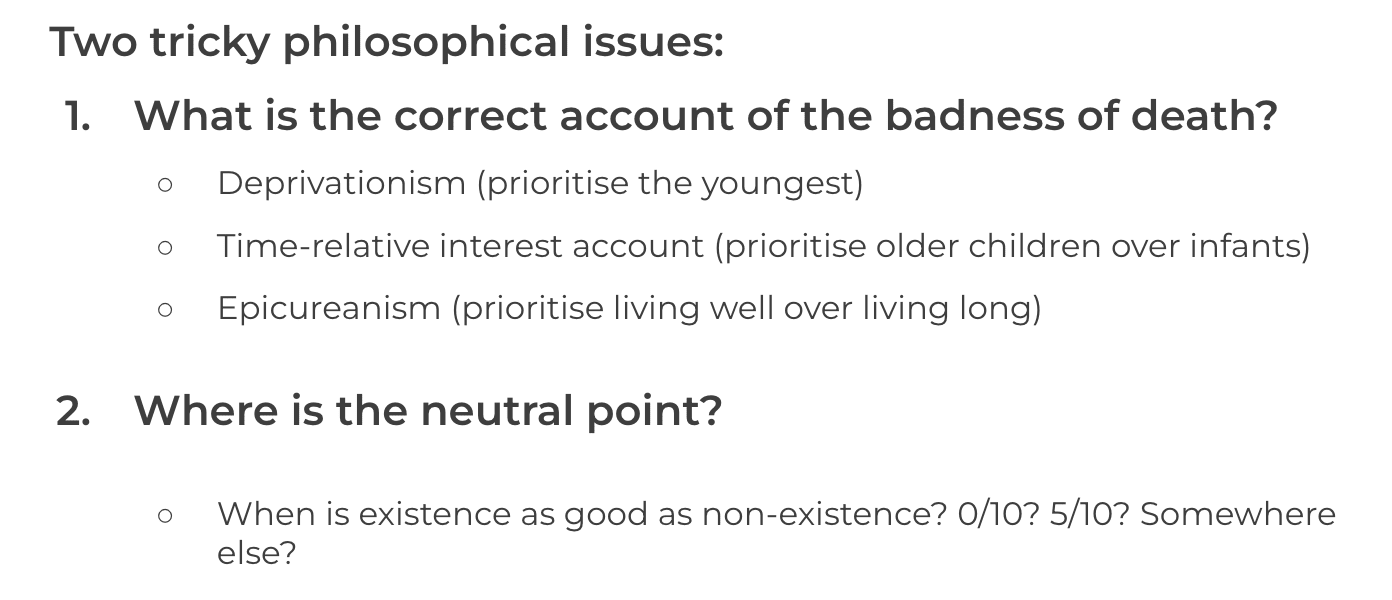

The further question is, “Okay, I've given you these quality-of-life interventions, but how does this compare to saving lives?” That's something that's very commonly popular. I was looking at this during my PhD as well. And what really surprised me is that there hasn't been very much attention given or recognition for the fact like this that actually these questions are just much more complicated than we might think. I'm not going to go through all of the details. But there are different philosophical issues about how bad death is. Does life start at birth? Is it better to save a young child than a newborn? Should living well be more important than in living long? And there's a further question of where the neutral point is. When is life as good as death? If you're putting it on your 0 to 10 scale, is it zero out of 10, 5 out of 10? Is it somewhere in between? How do we know? And these are genuinely difficult questions. There is no one simple answer for how to do the comparison. It's actually much more complicated than that.

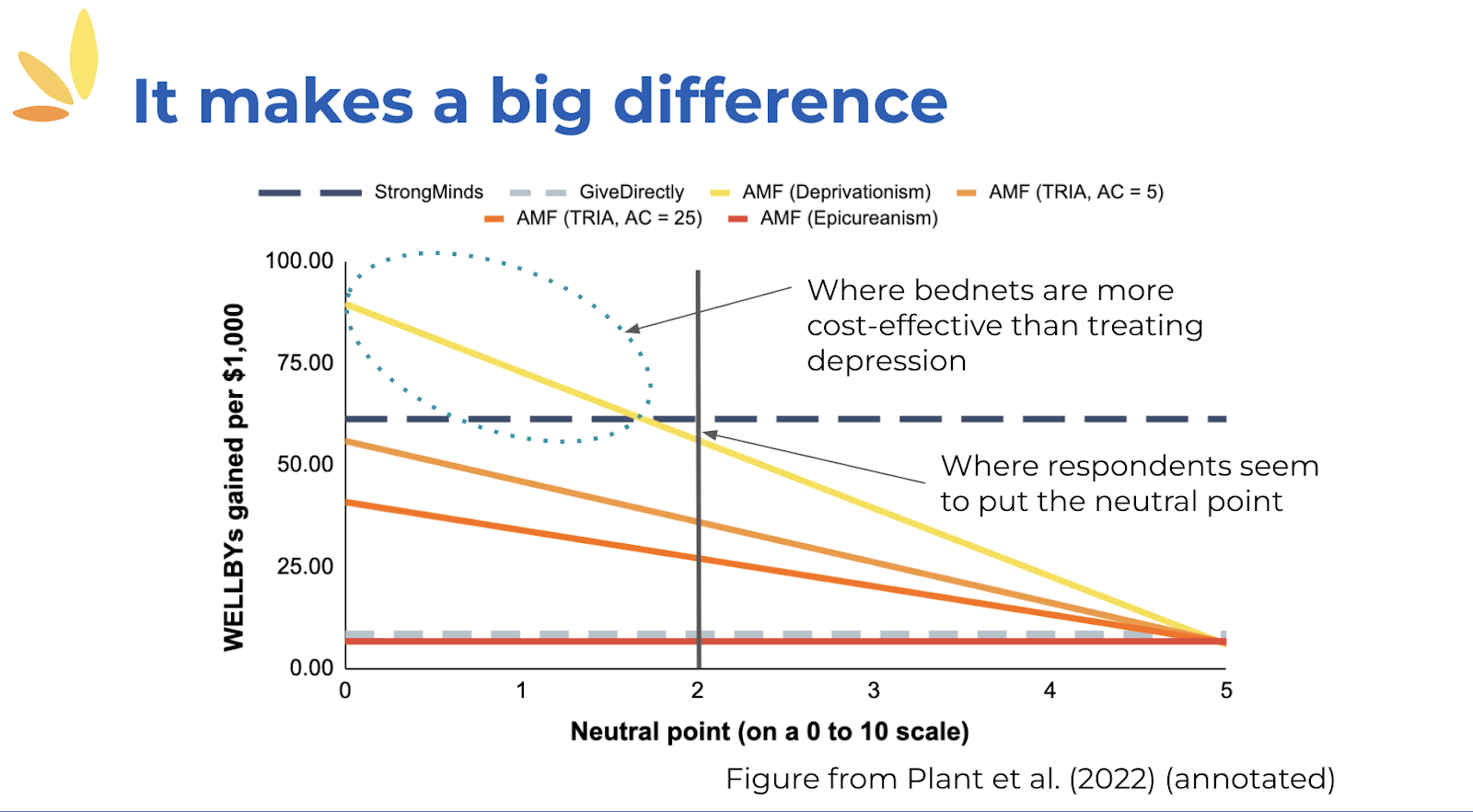

I don't have time to explain this, but using our well-being numbers, we looked at a range of a reasonable spread of opinions that we think you could have, and we found that it makes quite a big difference. There are some assumptions under which the bed nets end up being more cost-effective than the therapy. But under the rest of the assumptions, they end up not being more cost-effective, and they can be quite a lot less cost-effective. And so, it's almost unsurprisingly that your moral assumptions are going to do lots of the work here.

That's where we get to in the end. As I say, how you think about comparing improving lives and saving lives really depends upon the assumption. So we find it's sort of between 1 to 12 times as good as cash transfers. And then GiveWell ended up concluding it was about nine times better than cash transfers. But that's as a result of kind of plugging in their particular set of assumptions of the house view. And I think their assumptions are amongst the least favourable you could take towards saving lives.

Let me wrap up. What I hope I've been able to convince you of is that we should take happiness seriously and that we can. Happiness matters. We can measure it. We're often wrong about it and certainly, it's telling us a new story when we're focusing on improving people's lives. There's a really different picture from what we think matters from what perhaps does.

In the Happy Lives Institute, our next steps are to search for even more cost-effective interventions and organisations. We currently have one charity that we recommend, which is StrongMinds. We'd like to have other things that we recommend. It's not that we think that other things are terrible. That's just all we've been able to look at and vet.

We hope to have a couple of other things in mental health and not mental health by the end of this year. But that depends on how the research goes. We want to do foundational work on developing the well-being methodology, like working out some of the kinks. Such as, is your seven out of 10, the same as my seven out of 10? And then kind of broad global priorities research. One thing I'm starting to think about is if and how can the well-being approach help us with issues related to artificial intelligence. Is it part of the alignment problem? Maybe.

To remind you of what I said at the start, there are two goals here. There's the short-term goal which is just to find more impactful funding opportunities and we hope to do that. But really, the longer term piece is to change our paradigm, to think differently about measuring what matters and how we can do good and to engineer wider societal change as a result of that.

I think this is an exciting moment. The idea that we should take happiness seriously is an idea that stretches back to enlightenment, if not further. But now is the first time in human history we can do this in a scientific way. We can really find out what improves people's lives and realise this dream of working out how best to improve the human lot. So, I think this is a big moment. And, of course, you can help. You can help with your careers, your choice of jobs. You can help with your donations and you can help with your advocacy by promoting these ideas.

Victor Hugo said that nothing is as powerful as an idea whose time has come. I think this idea's time has come. Thank you.

Rejoinder (Oxford Wellbeing Research Center)

Thanks, Michael. So, I just want to thank Michael. Well, first everyone for coming. This is the biggest audience I've ever presented my nerd interests to. I really appreciate that. I want to thank Michael for inviting me to comment. As you'll see, my comments tend to be fairly spicy and provocative. So I think that was a very robust act on Michael's part.

I also want to preface my comments by saying that I broadly think that HLI’s work is a step in the right direction for effective altruism. Broadly, this idea that we should take subjective opinions about well-being seriously, I strongly agree with. I also think that the idea that we should focus on good lives, not just more lives is a very important consideration.

My concerns are more about happiness and life satisfaction as ways of cashing out well-being. I don't think that's a particularly good definition. I really don't like life satisfaction scales very much at all. But as Michael said, if you knew how the sausage was made on income measures and preference satisfaction measures, you might also be very concerned about them.

Like cognitive behavioural therapy, which is, as I understand it, what StrongMinds advocates for and is part of their intervention, is a fairly narrow conceptualization of and treatment for mental health. It's very important, but I worry sometimes that it takes oxygen away from a broader and richer understanding of mental health that would be less individualistic and less biomedical. One that takes more account of structural factors, sociological issues and then also the kind of narrative of a person's life and why they've developed mental health issues.

One of my biggest concerns and this is germane to effective altruism more generally is that there's a kind of fixation on a cost-benefit analysis and randomised control trials. I think that's quite harmful to a good understanding of well-being and interventions to improve it. And I stress the word fixation here. So it's not that these methods aren't important. It's that we shouldn't be narrowly fixated on them.

What is welfare/well-being?

As Bridget very kindly mentioned, I do have this book out where I talk a lot about all sorts of different theories of well-being and propose my own. I'm not gonna talk about it today. I just want to stress that there are a lot of different ways of thinking about well-being. And something that's I think not particularly well understood and so I thought I'd mention it briefly is that the DALY and QALY measures, like most theories of welfare coming out of economics, are grounded in what Michael called the desire satisfactions view, or the idea that what's good for you is getting what you want, is satisfying your preferences. So it's not that economists blindly just care about income because they're fools. The reason why they care about income is because it's a proxy for preference satisfaction.

Well-being theories

But there are a bunch of other well-being theories that I'm much more compelled by. Michael's list, understandably because it's his background, is really only presenting the canonical theories from analytical philosophy and is missing a very important one.

I would say the eudaimonic theory, which is that well-being is about living in a particular way in a way that accords with human nature. I don't really like the Aristotelian version of that. But out of psychology, you get eudaimonic theories that are what I would call functionalists. They really take seriously the kind of organism that a human is, what we have evolved to be, what it means for that organism to flourish, and what it means for it to be going well. And I think it's quite important for us when we think about mental health in particular, but also broadly when we conceptualise good lives to have this kind of rich functionalist account in there.

I think it's also very important to bring the perspective from geography, sociology, and epidemiology, which is broadly that well-being is an emergent property of complex social environmental structures or systems. So individual well-being is a function of the setting in which that individual is, and the well-being of that setting. The well-being of a community or a village, for example, is a function of the individuals in that setting. And we need to take seriously that kind of structural interaction.

I think both of these perspectives are especially crucial for understanding mental health. Less so perhaps, for understanding happiness.

Just giving a brief shout-out to the capabilities approach. The capabilities approach is the dominant theory of well-being in development policy and development studies globally. And it's basically the idea that well-being is a matter of having a large option set of possible lives from which to choose. So we're trying to expand what people can do with their life and what people can be in their life by giving them education, health, political enfranchisement, these sort of things.

Intrinsic vs instrumental

Now, the typical reaction of philosophers to these kinds of perspectives coming out of psychology and geography and et cetera is to say, “You're getting what's intrinsically well-being and what's merely instrumental to it confused. You're collapsing well-being as an outcome with the causes of well-being.” And the rejoinder to this in this kind of psych literature is to say that this is a false distinction. That actually the ingredients and the outcomes are bound up in such intimate ways that it's very difficult to separate them conceptually and more importantly, it's not useful. It's not a constructive thing to do to separate them.

So I'll try to give you one example: when we're thinking about the economic definition of well-being as preference satisfaction. Economists would argue that what makes your life go well is satisfying not any old preferences, but rational preferences, well-laundered preferences that you've really thought about and digested. And this cashes out very nicely when we're looking at optimal gambles. When we're thinking about things like how to save for retirement and you're thinking about the interest rate and how much money you have to invest in this kind of stuff. You can really think about that in formal, rational, mathematical terms.

But it doesn't work well for most preferences that you have in your life. It doesn't work well for thinking about what occupation should I have? What universities should I go to? Who should I be friends with? What should my hobbies be? These kinds of questions are not optimal gambles, really in any way. They're things that we think about when we’re thinking about how to be rational about those preferences. We might think of something like does satisfying these preferences integrate or harmonise my reasons? Why do I think this is a valuable thing to do with my time?

My motivations - do I actually get out of bed and go and do it on the basis of my reasons? And then my emotions - when I'm engaged in these things, do I feel good about it? Do I feel good about it? If you are engaged in a bunch of stuff that you think is very reasonable, you've been convinced by, I don't know Peter Singer, that you should do it. But you're really struggling to find motivation. Then you're not particularly, well-harmonised. And it's going to be very hard for you to maintain that behaviour. Equally if you're doing something that you have a lot of motivation for, perhaps because your parents are really putting a lot of pressure on you to do it. But it just makes you feel kind of crap, like you don't enjoy doing scales on the cello or the piano. Then again, you're not gonna be able to sustain that motivation. You're gonna feel bad about your life. You're probably gonna think your life is not going well.

So we're going to be looking for preferences that make sense of all these different aspects of our psychology. And we can see there that a lot of these distinctions, that philosophy makes kind of collapse when we take a step back from thinking about what well-being is to thinking about how we get it. When you're thinking more practically, you find that you need to think about hedonism and mental states. You need to think about the process. So this eudaimonic idea of how are we living? You need to think about what your preferences are and what your goals are in life, what you're trying to achieve. And you also need to think about all those items on the objective list that Michael mentioned, like knowledge and virtue that help if you achieve those things. This leads to this idea that well-being is a process as much as it is an outcome. And then statements like this from Michael Bishop's 2015 book, that well-being is a complex causal network. That all sorts of stuff is interrelated in it.

This is all getting complicated…

Now your reaction to this might be, “Mark, this is all getting way too complicated. We can't do robust analytical work with this kind of stuff. Can't we just use life satisfaction as a proxy for all this complexity that you've outlined? Can't we just do some randomised experiments, use some powerful statistical methods, and then we can all things held constant away all this structural sociological stuff that you're banging on about? And then we can just do some rigorous analysis. “

Now, I have some sympathy for this take, particularly that at the moment we assume a way, in cost-benefit analysis using income, a lot of important stuff like loneliness because we're not trading loneliness in markets and so we can't put a price on it. And doing life satisfaction analysis allows us to fold more of these important things into our policy analysis.

But broadly speaking, I think this is the wrong way of thinking about what we're doing here. What this is doing is assuming away the complexity and then thinking that you've got something really rigorous left behind. But actually, you've assumed away all the important stuff.

I think this is very representative of Urizen. I don't know if people here are familiar with Urizen. This is a figure from William Blake's mythology. William Blake is a very famous British painter. Urizen is his personification of reason gone overboard. So reason kind of forgets this glowing heavenly place from which it's come, reaches out into the darkness with its measurement instrument, divides the world into categories, and from there thinks that it has solved all the problems and it knows everything. But actually, it's forgotten all the important stuff.

The analysis is not rigorous

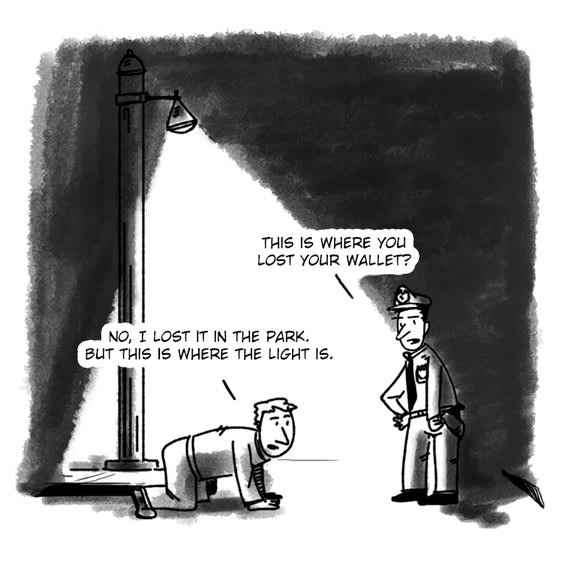

Now, if that metaphor was a bit too woo for you, the slightly more accessible way of thinking about this is the spotlight problem. You've lost your keys and you're not looking for them where you lost them, but where the light is.

I think broadly what I'm getting at is that in just using life satisfaction as a proxy for this more complex notion of well-being, in assuming away a lot of this complexity analysis statistical models, we're not actually getting to more rigorous analysis. We're getting to a dumber analysis.

Now, I don't want to go into the ins and outs of the cost-benefit analysis that was done on StrongMinds and that Michael's team has done. I think they've done a really good job of it. There is this really good forum post on the EA forums that goes into a lot of the ins and outs of that if you are interested.

One point that I do want to draw your attention to is that one of the main concerns around that cost-benefit analysis was that people were kind of giving an indication to the interviewer that the StrongMinds intervention had been really effective because they thought that in so doing, they would be given more money. Now, that might raise concerns about the cost-benefit analysis. But what it really undermines for me is that in order to understand what's going on here, we need qualitative methods.

Now, this is part of what we call causal process tracing, and I think this is becoming increasingly common in even the most extreme sort of ideologue randomised controlled trial circles that you need to have qualitative aspects to a lot of your randomised interventions in order to understand what happened, to get a kind of rich sense of how things work, not just whether they work.

I think a similar kind of story with the searchlight problem when we think about cognitive behavioural therapy, it's very useful to do cognitive behavioural therapy. It's a really good treatment for a lot of symptoms of mental health. It can even treat some of the causes of mental health, like people ruminating on their body image. But, potentially, if you use it as a narrow lens for understanding mental health, it's gonna distract you from deep and complex issues like bipolar disorder, and complex trauma. And these sort of things are quite prominent in the context in which a lot of effective altruists would like to take action. In a lot of developing countries, you have heaps of trauma, domestic violence, poverty, histories of warfare, this kind of stuff that give rise to very complex mental health issues, in which case CBT is a bit too narrow a lens.

Now, maybe you'd say that this band-aid is still valuable. I think that's absolutely true. My concern is again just about a reductionist approach and missing the forest for the trees. A big concern with not taking these structural issues seriously and understanding the context in which we're working is that the external validity of any randomised control trial that you do is poop because you're not gonna be able to replicate the context in any other further situation. So as much as you've got wonderful internal validity there, you don't have external validity. So the value of that exercise is really not that high.

Subjective measures

A brief word on subjective measures. I love subjective measures, I completely agree with Michael that we need to take subjective measures more seriously. I'm even more extreme than Michael. I think we should take qualitative data from therapy sessions into consideration. That's how hardcore I am about subjective measures. I also think we could use a lot of these longer psychometric methods, like the well-being profile which in the short form is 15 questions.

My concern with life satisfaction scales… Michael alluded to some of these issues. This is ongoing work. Michael is part of an adversarial collaboration with me and some other colleagues. I'm the most sceptical. Michael is probably the most optimistic. I'm very concerned about the interpersonal comparability of these instruments.

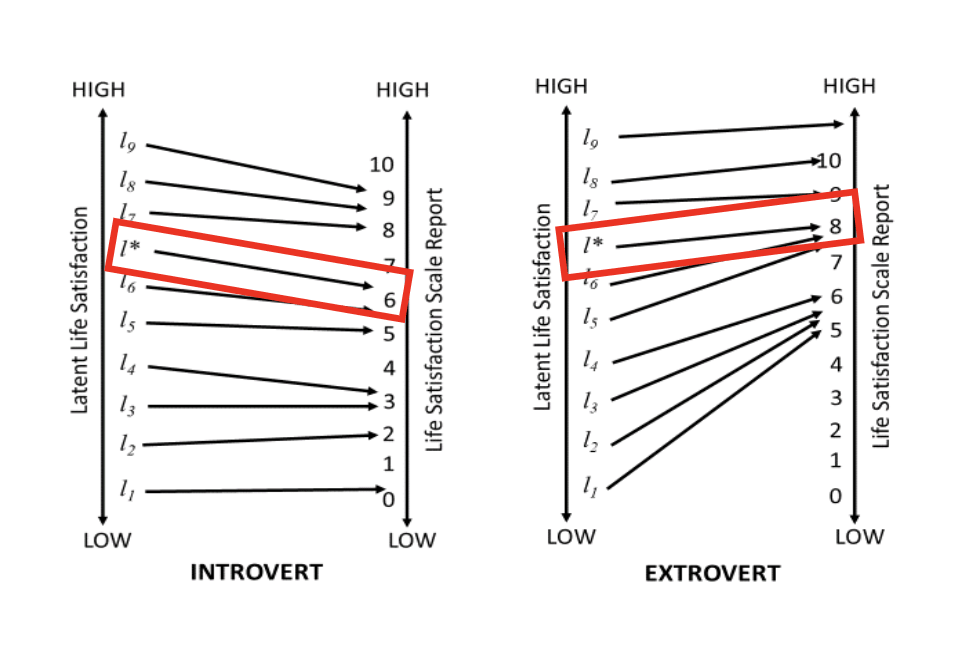

Imagine two individuals, right? They have exactly the same life. And not only do they have exactly the same life, but they assess that life exactly the same way. So in their minds, they make the same assessment as to how well their life is going. What's different about these two individuals is how they map that assessment into the response categories on the scale. So exactly the same people exactly the same lives. This person maps that life L I star into a six on the scale. This other person maps that into an eight on the scale. And so we, as the researcher see the eight and think that the other person is better off than the first person. But they are, in fact, exactly the same. They just have different reporting functions. And we're only now starting to do work unpacking the reporting function. And I think that work is pretty scary. But, as I said adversarial collaboration. Maybe my colleagues will have less concern about the things that we're finding. And we keep an eye out for that research.

There are alternative approaches

I want to stress here that I really love randomised control trials. I love cost-benefit analysis. My first book advocated for all that sort of stuff was broadly technocratic, love evidence-based policy. What I'm really advocating for is to use some of the still very robust, complementary, or additional approaches. And I'm thinking in particular of agent-based models. Agent-based models are capable of embedding individuals in structures and then looking at how those structures affect all sorts of interventions that we might put into play into those structures. These came out of people who were dissatisfied with what they were learning from randomised controlled trials. So we did tonnes and tonnes, hundreds of randomised controlled trials and obesity interventions. And we just found that they weren't really telling us much because every intervention was contingent on everything else going on in the system. So we then took the coefficients from those interventions, used them to initially parameterize an agent-based model, and then run simulations so that we can learn how things work in the structure. I'm not suggesting that HLI and the effective altruism movement more broadly need to use really woolly-like sample size of five qualitative methods. But I am suggesting that we need to use agent-based models, causal process tracing, and some of the more sophisticated mixed methods that are out there. This is not something that you come across in the economic space at the moment. So I think broadly, we need to get out of the economic space and into the wider discourse. I would like to see a much more thorough engagement with philosophy of science in this space. Science is not necessarily about experiments, and it's not about confirming things. It's not about certainty. It's about falsification - what, you don't know, not what you do know.

So just back to deworming?

I've got to stress that this is not exclusive to the Happier Lives Institute and the work they're doing. I think this is generally germane to effective altruism. So the effectiveness is really analytical effectiveness. It's about what can we know with certainty not what seems to be having the big impact.

The iconic case of this or the archetype was this big debate in development economics between Lance Pritchard and the randomistas (Esther Delo and Abhijit Banerjee) where Pritchard was arguing that the biggest effect on anti-poverty in the last 50 years has been the rise of the Asian tiger economies. This was driven by things like commerce, institutions, industrialization, all things that we can't do randomised controlled trials and cost-benefit analysis on but are massively impactful. And so the idea here is do we want to be certain? Is that what is effective? Or do we want to be right and have a big effect?

What’s the upshot?

OK, so what's my upshot to conclude? I totally agree with Michael that effective altruism should think harder about well-being. What does it mean for a life to go well? How can we promote good lives, not just more lives? However, I think that we should think about good life in a multidimensional way, in a rich way that takes into account structure and sociological conditions. I think we shouldn't fixate on RCTs and CBA and shouldn't use them as a hammer in search of nails. Effective treatments for complex problems are likely to be messy, and we need to develop epistemic frameworks for appreciating that messiness and tolerating it, not assuming it away.

All right, thanks very much.

Hi Mark, I found your perspective really interesting. Your critiques make a lot of sense, but I’m unclear on what using the mixed methods you mention would look like in practice. Is there anywhere you can point us to in order to learn more about the approaches to deciding what interventions to prioritise that you advocate for?