As of July 2021, over 6,000 people have taken The Giving What We Can Pledge to give at least 10% of their lifetime incomes to highly effective charities.

These people could have easily:

- Given without pledging to give;

- Given without focusing on charity effectiveness; or

- Just kept the money for themselves.

So why have they committed to taking significant action to effectively help others? We asked them.

Background

Our team at Giving What We Can has taken on the mission of inspiring donations to the world's most effective organisations. One way in which we do that is by building a community of people who've pledged to give a meaningful portion of their income to effective charities.

To build this community, it is important to understand why people have taken (and upheld) an effective giving pledge. In a world of information overload, our attention is limited. We often only have a few seconds — or even just a glance — to reach someone, so understanding our existing members' motivations is an important first step in understanding what might motivate other people to join a community of people committed to giving more, and more effectively.

This might seem straightforward, but we discovered that there were so many different motivations that it was hard to know which ones were most important to lead with. Without a clear understanding of the most compelling messages, we could be missing out on significant community growth – and thus potentially missing out on billions of dollars that could be donated to highly effective charities.

Methods

To understand the strongest motivations of our members, we started by looking at two data sources:

- The pledge sign-up survey (where people left comments about their motivations in the "anything else to add" field) and;

- A list of quotes from member stories on the GWWC website

We then coded these statements with relevant keywords that captured the underlying messages.

For example, the statement: "Being financially in a luckier position than most of the world, I feel like it is a moral duty to contribute to the good for humanity in general" was grouped with similar messages that were coded with keywords like "moral duty", "income inequality", and "financial stewardship".[1]

Once themes emerged, we tried to capture these themes in various key messages.

In some cases, we included two very similar messages if we wanted to tease apart two similar ideas that had an important distinction (for example, income inequality creating an obligation to help others versus an opportunity to help others).

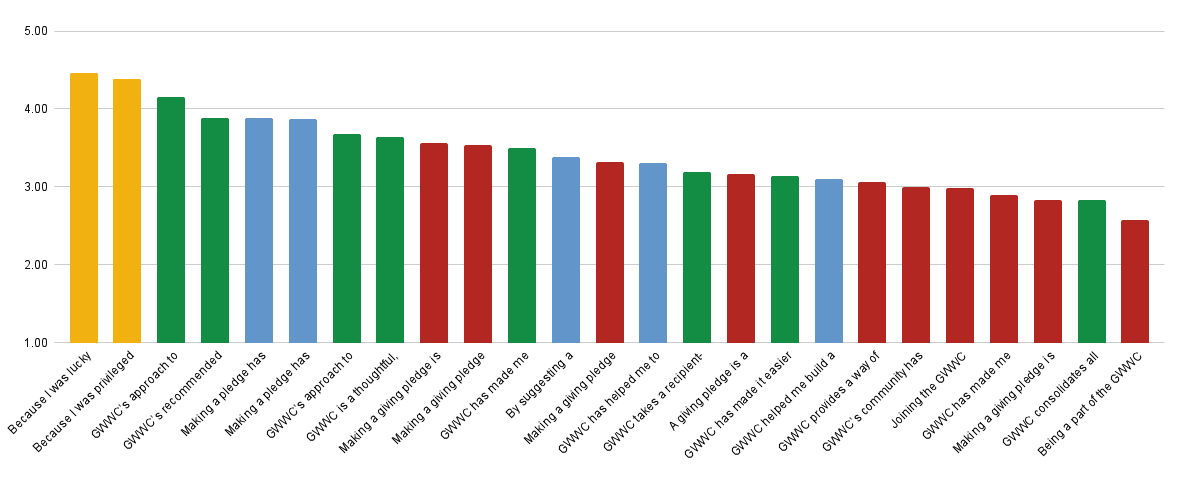

This resulted in a list of 25 key message statements, which represented most of the motivations identified.

We then asked our members to rate these statements on a five-point scale from "not at all motivating" to "highly motivating", and also by picking their top three motivations.[2] 124 members responded. Note that our sample is subject to selection bias, and please understand this work as an exploratory project, not as a formal study.

Results

The 25 statements fell broadly into four motivational categories, which we labelled as inequality, emotion, effectiveness, and convenience after doing an exploratory factor analysis.[3]

Two statements seemed to resonate with our members more than the rest: these were the two related to global income inequality.[4]

- The Opportunity Framing: "Because I was lucky enough to be born in a relatively wealthy nation, I have the opportunity to help those who need it."

- The Responsibility Framing: "Because I was privileged to be born in a relatively wealthy nation, I have a responsibility to help those who need it."

This might be because this global income inequality messaging has been very prominent over the years at Giving What We Can. After all, the How Rich Am I? calculator is the most visited page on GivingWhatWeCan.org and it also features on the homepage. This calculator shows that most people in high-income countries are in the top global 5% and that they could use that income to significantly benefit others.

What is particularly interesting is the difference in ratings between these two framings. The responsibility framing was almost twice as popular when members were asked to select three primary motivations. Almost half the members selected this motivation. However, the opportunity framing had a higher mean score because a small number of members gave the responsibility framing a very low rating. This suggests that the responsibility framing is more popular — but also more polarising — than the opportunity framing.[5]

The next two highest-scoring statements were related to charity effectiveness:

- GWWC's approach to giving is rational and impact-focused.

- GWWC's recommended charities[6] are rigorously vetted and evidence-based[7].

Impact appears to be a highly motivating factor and many members believe that the way to achieve that desired impact is by using evidence and rigour.

The effectiveness statements were incredibly closely followed by two statements that fell in the convenience group of statements, but both specifically focused on how making a pledge helps people follow through:

- Making a pledge has helped me to act in better accordance with my own values.

- Making a pledge has helped me build a long-term habit around charitable giving; it will keep me accountable over time.

Most of the emotion-related motivations ranked lower than the other groups of statements. However, they were still predominantly averaging "moderately motivating" or higher. The outlier of the emotion group was one that related to meaning and purpose. While its average score ranked 10th (out of 25), it was the third-most selected when members could only pick three motivations:

- Making a giving pledge provides meaning or purpose in my life.

Full data table available here

Conclusion

This project was exploratory in nature. We have much more work to do before we can fully understand these motivations and which ones will resonate most with new potential members. In particular, we'd like to develop an understanding of the extent to which the motivations of our current members can also motivate new members. At this stage, a few things seem pretty clear as motivators:

- People with means have an enormous opportunity to help others;

- They can have a much bigger impact if they donate effectively;

- Committing to act on this opportunity can help them to follow through on their plans to give; and

- Following through can help bring meaning and purpose to the lives of these committed effective givers.

Please let me know in the comments what you think about this research, anything that resonated with you, or anything we might have missed.

To give you a bit of motivation I'll leave you with two open text responses written by Mike from the UK and Patrick from Germany, both of which resonated with me personally:

"We did not choose to be who we are, so if we are lucky, then we should be sharing that luck with others where we can." - Mike, UK

"It's motivating to know that you can help many humans and animals and being part of a group of people that also value this. Being an effective giver gives me purpose and has become an important part of my identity." - Patrick, Germany